User login

A black 37-year-old man has gradually lost 100 lb (45 kg) over the past 2 years, and reports progressive fatigue and malaise as well. He has not noted swollen lymph nodes, fever, or night sweats. He denies dyspnea, cough, or chest pain. He has no skin rashes, and no dry or red eyes or visual changes. He reports no flank pain, dysuria, frank hematuria, foamy urine, decline in urine output, or difficulty voiding.

He has no history of significant medical conditions. He does not drink, smoke, or use recreational drugs. He is not taking any prescription medications and has not been using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combination analgesics. He does not have a family history of kidney disease.

Physical examination. He appears relaxed and comfortable. He does not have nasal polyps or signs of pharyngeal inflammation. He has no apparent lymphadenopathy. His breath sounds are normal without rales or wheezes. Cardiac examination reveals a regular rhythm, with no rub or murmurs. The abdomen is soft and nontender with no flank pain or groin tenderness. The skin is intact with no rash or nodules.

- Temperature 98.4ºF (36.9ºC)

- Blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg

- Heart rate 102 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 19 per minute

- Oxygen saturation 99% while breathing room air

- Weight 194 lb (88 kg)

- Body mass index 28 kg/m2.

Laboratory testing (Table 1) reveals severe renal insufficiency with anemia:

- Serum creatinine 9 mg/dL (reference range 0.5–1.2)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 8 mL/min/1.73m2 (using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation).

His serum calcium level is normal, but his serum phosphorus is 5.3 mg/dL (reference range 2.5–4.6), and his parathyroid hormone level is 317 pg/mL (12–88), consistent with hyperparathyroidism secondary to chronic kidney disease. His 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is less than 13 ng/mL (30–80), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is 129 U/L (9–67 U/L). His urinary calcium level is less than 3.0 mg/dL.

Urinalysis:

- Urine protein 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- No urine crystals

- 3 to 5 coarse granular urine casts per high-power field

- No hematuria or pyuria.

Renal ultrasonography shows normal kidneys with no hydronephrosis.

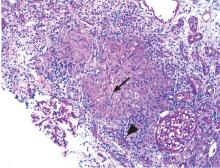

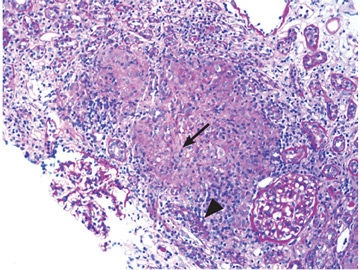

Renal biopsy study demonstrates noncaseating granulomatous interstitial nephritis (Figure 1).

GRANULOMATOUS INTERSTITIAL NEPHRITIS

1. Based on the information above, what is the most likely cause of this patient’s kidney disease?

- Medication

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Infection

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a histologic diagnosis that is present in up to 1% of renal biopsies. It has been associated with medications, infections, sarcoidosis, crystal deposits, paraproteinemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis and also is seen in an idiopathic form.

Medicines implicated include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, NSAIDs, allopurinol, and diuretics.

Mycobacteria and fungi are the main infective causes and seem to be the main causative factor in cases of renal transplant.1 Granulomas are usually not found on kidney biopsy in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and that diagnosis is usually made by the presence of antiproteinase 3 antibodies.2

Sarcoidosis is the most likely diagnosis in this patient after excluding implicated medications, infection, and vasculitis and confirming the presence of granulomatous interstitial nephritis on renal biopsy.

SARCOIDOSIS: A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown cause, characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. It can involve any organ but most commonly the thoracic and peripheral lymph nodes.3,4 Involvement of the eyes and skin is also relatively common.

Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in more than 30% of cases of sarcoidosis, almost always with concomitant thoracic involvement.5,6 Isolated extrathoracic sarcoidosis is unusual, found in only 2% of patients in a sarcoidosis case-control study.5

Current theory suggests that sarcoidosis develops from a cell-mediated immune response triggered by one or more unidentified antigens in people with a genetic predisposition.7

Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all ages, most often adults ages 20 to 40; but more recently, it has increased in US adults over age 55.8 The condition is more prevalent in Northern Europe and Japan, and in blacks in the United States.7

HOW COMMON IS RENAL INVOLVEMENT IN SARCOIDOSIS?

2. What is the likelihood of finding clinically apparent renal involvement in a patient with sarcoidosis?

- Greater than 70%

- Greater than 50%

- Up to 50%

- Less than 10%

The prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is hard to determine due to differences in study design and patient populations included in the available reports, and because renal involvement may be silent for many years. Recent studies have reported impaired renal function in 0.7% to 9.7% of cases: eg, a case-control study of 736 patients reported clinically apparent renal involvement in 0.7% of patients,5 and in a series of 818 patients, the incidence was 1%.9 In earlier studies, depending on the diagnostic criteria, the incidence ranged from 1.1% to 9.7%.10

The prevalence of renal involvement may also be underestimated because it can be asymptomatic, and the number of granulomas may be so few that they are absent in a small biopsy specimen. A higher prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is reported from autopsy studies, although many cases remained clinically silent. These studies have reported renal noncaseating granulomas in 7% to 23% of sarcoidosis patients.11–13

PRESENTATION OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

3. What is the most common presentation in isolated renal sarcoidosis?

- Sterile pyuria

- Elevated urine eosinophils

- Renal insufficiency

- Painless hematuria

Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis include hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and impaired renal function.14 Renal involvement can occur during the course of existing sarcoidosis, at the time of first presentation, or even as the sole presentation of the disease.1,11,15 In patients with isolated renal sarcoidosis, the most common presentation is renal insufficiency.15,16

Two main pathways for nephron insult that have been validated are granulomatous infiltration of the renal interstitium and disordered calcium homeostasis.11,17 Though extremely rare, various types of glomerular disease, renal tubular defects, and renal vascular involvement such as renal artery granulomatous angiitis have been documented.18

Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is known to cause hypercalcemia by increasing calcium absorption secondary to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production from granulomas. Our patient’s case is unusual, as renal failure was the sole extrapulmonary manifestation of sarcoidosis without hypercalcemia.

In sarcoidosis, extrarenal production of 1-alpha-hydroxylase by activated macrophages inappropriately increases levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol). Subsequently, serum calcium levels are increased. Unlike its renal equivalent, granulomatous 1-alpha-hydroxylase evades the normal negative feedback of hypercalcemia, so that increased calcitriol levels are sustained, leading to hypercalcemia, often accompanied by hypercalciuria.19

Disruption of calcium homeostasis affects renal function through several mechanisms. Hypercalcemia promotes vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole, leading to a reduction in the GFR. Intracellular calcium overload can contribute to acute tubular necrosis and intratubular precipitation of calcium, leading to tubular obstruction. Hypercalciuria predisposes to nephrolithiasis and obstructive uropathy. Chronic hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, if untreated, cause progressive interstitial inflammation and deposition of calcium in the kidney parenchyma and tubules, resulting in nephrocalcinosis. In some cases, nephrocalcinosis leads to chronic kidney injury and renal dysfunction.

HISTOLOGIC FEATURES

4. What is the characteristic histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis?

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Minimal change disease

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis

- Immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the most typical histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis.4,20–22 However, interstitial nephritis without granulomas is found in up to one-third of patients with sarcoid interstitial nephritis.15,23

Patients with sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis usually present with elevated serum creatinine with or without mild proteinuria (< 1 g/24 hours).1,15,16 Advanced renal failure (stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease) is relatively common at the time of presentation.1,15,16 In the 2 largest case series of renal sarcoidosis to date, the mean presenting serum creatinine levels were 3.0 and 4.8 mg/dL.11,15 The most common clinical syndrome associated with sarcoidosis and granulomatous interstitial nephritis is chronic kidney disease with a decline in renal function, which if untreated can occur over weeks to months.21 Acute renal failure as an initial presentation is also well documented.15,24

Even though glomerular involvement in sarcoidosis is rare, different kinds of glomerulonephritis have been reported, including membranous glomerulonephritis, mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental sclerosis, and crescentic glomerulonephritis.25

DIAGNOSIS OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

5. How is renal sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- By exclusion

- Complete urine analysis and renal function assessment

- Renal biopsy

- Computed tomography

- Renal ultrasonography

The diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis is one of exclusion. Sarcoidosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of renal failure of unknown origin, especially if disordered calcium homeostasis is also present. If clinically suspected, diagnosis usually requires pathohistologic demonstration of typical granulomatous lesions in the kidneys or in one or more organ systems.26

In cases of sarcoidosis with granulomatous interstitial nephritis with isolated renal failure as a presenting feature, other causes of granulomatous interstitial nephritis must be ruled out. A number of drug reactions are associated with interstitial nephritis, most commonly with antibiotics, NSAIDs, and diuretics. Although granulomatous interstitial nephritis may develop as a reaction to some drugs, most cases of drug-induced interstitial nephritis do not involve granulomatous interstitial nephritis.

Other causes of granulomatous interstitial infiltrates include granulomatous infection by mycobacteria, fungi, or Brucella; foreign-body reaction such as cholesterol atheroemboli; heroin; lymphoma; or autoimmune disease such as tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or Crohn disease.27,28 The absence of characteristic kidney biopsy findings does not exclude the diagnosis because renal sarcoidosis can be focal and easily missed on biopsy.29

Urinary manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are usually not specific. In renal sarcoidosis with interstitial nephritis with or without granulomas, proteinuria is mild or absent, usually less than 1.0 g/day.11,15,16 Urine studies may show a “bland” sediment (ie, without red or white blood cells) or may show sterile pyuria or microscopic hematuria. In glomerular disease, more overt proteinuria or the presence of red blood cell casts is more typical.

Hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis are nonspecific abnormalities that may be present in patients with sarcoidosis. In this regard, an elevated urine calcium level may support the diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis.

Computed tomography and renal ultrasonography may aid in diagnosis by detecting nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis.

The serum ACE level is elevated in 55% to 60% of patients with sarcoidosis, but it may also be elevated in other granulomatous diseases or in chronic kidney disease from various causes.5 Therefore, considering its nonspecificity, the serum ACE level has a limited role in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.30 Using the ACE level as a marker for disease activity and response to treatment remains controversial because levels do not correlate with disease activity.5,11

TREATMENT OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

6. Which is a first-line therapy for renal sarcoidosis?

- Corticosteroids

- Azathioprine

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Infliximab

- Adalimumab

Treatment of impaired calcium homeostasis in sarcoidosis includes hydration; reducing intake of calcium, vitamin D, and oxalate; and limiting sun exposure.11,31 For more significant hypercalcemia (eg, serum calcium levels > 11 mg/dL) or nephrolithiasis, corticosteroid therapy is the first choice and should be implemented at the first sign of renal involvement. Corticosteroids inhibit the activity of 1-alpha-hydroxylase in macrophages, thereby reducing the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have been mentioned in the literature as alternatives to corticosteroids.32 But the effect of these agents is less predictable and is slower than treatment with corticosteroids. Ketoconazole has no effect on granuloma formation but corrects hypercalcemia by inhibiting calcitriol production, and can be used as an adjunct for treating hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria.

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis, including granulomatous interstitial nephritis and interstitial nephritis without granulomas. Most patients experience significant improvement in renal function. However, full recovery is rare, likely as a result of long-standing disease with some degree of already established irreversible renal injury.16

Corticosteroid dosage

There is no standard dosing protocol, but patients with impaired renal function due to biopsy-proven renal sarcoidosis should receive prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day, depending on the severity of the disease, in a single dose every morning.

The optimal dosing and duration of maintenance therapy are unknown. Based on studies to date, the initial dosing should be maintained for 4 weeks, after which it can be tapered by 5 mg each week down to a maintenance dosage of 5 to 10 mg/day.4

Patients with a poor response after 4 weeks tend to have a worse renal outcome and are more susceptible to relapse.15 Fortunately, relapse often responds to increased corticosteroid doses.11,15 In the case of relapse, the dose should be increased to the lowest effective dose and continued for 4 weeks, then tapered more gradually.

A total of 24 months of treatment seems necessary to be effective and to prevent relapse.15 Some authors have proposed a lifelong maintenance dose for patients with frequent relapses, and some propose it for all patients.4

Other agents

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-blocking agents. Considering the critical role TNF plays in granuloma formation, anti-TNF-alpha agents are useful in steroid-resistant sarcoidosis.33 A thorough workup is necessary before starting these agents because of the increased risk of serious infection, including reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Of the current TNF-blocking agents, infliximab is most often used in renal sarcoidosis.34 Experience with adalimumab is more limited, though promising results indicate it could be an alternative for patients who do not tolerate infliximab.35

Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate may also be used as a second-line agent if treatment with corticosteroids is not tolerated or does not control the disease. The evidence in support of these agents is limited. In small series, they have allowed sustainable control of renal function while reducing the steroid dose. Currently, these agents are used for patients resistant to corticosteroid therapy, who would otherwise need prolonged high-dose corticosteroid treatment, or who have corticosteroid intolerance; they allow a more effective steroid taper and maintenance of stable renal function.15,36

The data supporting a standardized treatment of renal sarcoidosis are limited. For steroid intolerance or resistance, cytotoxic drugs and selected anti-TNF-alpha agents, as mentioned above, have shown promise in improving or stabilizing serum creatinine levels. Further exploration is required as to which agent or combination is better at limiting the disease process with fewer adverse effects.

Our patient was initially treated with corticosteroids and was ultimately weaned to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day. He was followed as an outpatient and was started on mycophenolate mofetil in place of higher steroid doses. His renal function stabilized, but he was lost to follow-up after 2 years.

KEY POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly involves the lungs, skin, and reticuloendothelial system.

- Renal involvement in sarcoidosis is likely underestimated due to its often clinically silent nature and the possibility of missing typical granulomatous lesions in a small or less-than-optimal biopsy sample.

- Manifestations of renal sarcoidosis include disrupted calcium homeostasis, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and renal failure.

- Because the clinical and histopathologic manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are nonspecific, the diagnosis is one of exclusion. In patients with renal failure or with hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria of unknown cause, renal sarcoidosis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Patients with chronic sarcoidosis should also be screened for renal impairment.

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the classic histologic finding of renal sarcoidosis. Nonetheless, up to one-third of patients have interstitial nephritis without granulomas.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis. An initial dose of oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day should be maintained for 4 weeks and then gradually tapered to 5 to 10 mg/day for a total of 24 months. Some patients require lifelong therapy.

- Several immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents may be used in cases of corticosteroid intolerance or to aid in effective taper of corticosteroids.

- Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2:222–230.

- Lutalo PM, D'Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener's granulomatosis). J Autoimmun 2014; 48–49:94–98.

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1224–1234.

- Rajakariar R, Sharples EJ, Raftery MJ, Sheaff M, Yaqoob MM. Sarcoid tubulo-interstitial nephritis: long-term outcome and response to corticosteroid therapy. Kidney Int 2006; 70:165–169.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al; Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) research group. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1885–1889.

- Rizzato G, Palmieri G, Agrati AM, Zanussi C. The organ-specific extrapulmonary presentation of sarcoidosis: a frequent occurrence but a challenge to an early diagnosis. A 3-year-long prospective observational study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004; 21:119–126.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2153–2165.

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13:1244–1252.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med 1983; 52:525–533.

- Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE, Scott JH. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med 1963; 35:67–89.

- Berliner AR, Haas M, Choi MJ. Sarcoidosis: the nephrologist's perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:856–870.

- Longcope WT, Freiman DG. A study of sarcoidosis; based on a combined investigation of 160 cases including 30 autopsies from The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 1952; 31:1–132.

- Branson JH, Park JH. Sarcoidosis hepatic involvement: presentation of a case with fatal liver involvement; including autopsy findings and review of the evidence for sarcoid involvement of the liver as found in the literature. Ann Intern Med 1954; 40:111–145.

- Muther RS, McCarron DA, Bennett WM. Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141:643–645.

- Mahevas M, Lescure FX, Boffa JJ, et al. Renal sarcoidosis: clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentation and outcome in 47 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009; 88:98–106.

- Robson MG, Banerjee D, Hopster D, Cairns HS. Seven cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of extrarenal sarcoid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:280–284.

- Casella FJ, Allon M. The kidney in sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993; 3:1555–1562.

- Rafat C, Bobrie G, Chedid A, Nochy D, Hernigou A, Plouin PF. Sarcoidosis presenting as severe renin-dependent hypertension due to kidney vascular injury. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7:383–386.

- Reichel H, Koeffler HP, Barbers R, Norman AW. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by cultured alveolar macrophages from normal human donors and from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 65:1201–1209.

- Brause M, Magnusson K, Degenhardt S, Helmchen U, Grabensee B. Renal involvement in sarcoidosis—a report of 6 cases. Clin Nephrol 2002; 57:142–148.

- Hannedouche T, Grateau G, Noel LH, et al. Renal granulomatous sarcoidosis: report of six cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1990; 5:18–24.

- Kettritz R, Goebel U, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of sarcoidosis revisited. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:2690–2694.

- Bergner R, Hoffmann M, Waldherr R, Uppenkamp M. Frequency of kidney disease in chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003; 20:126–132.

- O’Riordan E, Willert RP, Reeve R, et al. Isolated sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis: review of five cases at one center. Clin Nephrol 2001; 55:297–302.

- Gobel U, Kettritz R, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of renal sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:616–623.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Bijol V, Mendez GP, Nose V, Rennke HG. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases from a single institution. Int J Surg Pathol 2006; 14:57–63.

- Mignon F, Mery JP, Mougenot B, Ronco P, Roland J, Morel-Maroger L. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 1984; 13:219–245.

- Shah R, Shidham G, Agarwal A, Albawardi A, Nadasdy T. Diagnostic utility of kidney biopsy in patients with sarcoidosis and acute kidney injury. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2011; 4:131–136.

- Studdy PR, Bird R. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis—its value in present clinical practice. Ann Clin Biochem 1989; 26:13–18.

- Demetriou ET, Pietras SM, Holick MF. Hypercalcemia and soft tissue calcification owing to sarcoidosis: the sunlight-cola connection. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25:1695–1699.

- Beegle SH, Barba K, Gobunsuy R, Judson MA. Current and emerging pharmacological treatments for sarcoidosis: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013; 7:325–338.

- Roberts SD, Wilkes DS, Burgett RA, Knox KS. Refractory sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Chest 2003; 124:2028–2031.

- Ahmed MM, Mubashir E, Dossabhoy NR. Isolated renal sarcoidosis: a rare presentation of a rare disease treated with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26:1346–1349.

- Gupta R, Beaudet L, Moore J, Mehta T. Treatment of sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis with adalimumab. NDT Plus 2009; 2:139–142.

- Moudgil A, Przygodzki RM, Kher KK. Successful steroid-sparing treatment of renal limited sarcoidosis with mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Nephrol 2006; 21:281–285.

A black 37-year-old man has gradually lost 100 lb (45 kg) over the past 2 years, and reports progressive fatigue and malaise as well. He has not noted swollen lymph nodes, fever, or night sweats. He denies dyspnea, cough, or chest pain. He has no skin rashes, and no dry or red eyes or visual changes. He reports no flank pain, dysuria, frank hematuria, foamy urine, decline in urine output, or difficulty voiding.

He has no history of significant medical conditions. He does not drink, smoke, or use recreational drugs. He is not taking any prescription medications and has not been using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combination analgesics. He does not have a family history of kidney disease.

Physical examination. He appears relaxed and comfortable. He does not have nasal polyps or signs of pharyngeal inflammation. He has no apparent lymphadenopathy. His breath sounds are normal without rales or wheezes. Cardiac examination reveals a regular rhythm, with no rub or murmurs. The abdomen is soft and nontender with no flank pain or groin tenderness. The skin is intact with no rash or nodules.

- Temperature 98.4ºF (36.9ºC)

- Blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg

- Heart rate 102 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 19 per minute

- Oxygen saturation 99% while breathing room air

- Weight 194 lb (88 kg)

- Body mass index 28 kg/m2.

Laboratory testing (Table 1) reveals severe renal insufficiency with anemia:

- Serum creatinine 9 mg/dL (reference range 0.5–1.2)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 8 mL/min/1.73m2 (using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation).

His serum calcium level is normal, but his serum phosphorus is 5.3 mg/dL (reference range 2.5–4.6), and his parathyroid hormone level is 317 pg/mL (12–88), consistent with hyperparathyroidism secondary to chronic kidney disease. His 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is less than 13 ng/mL (30–80), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is 129 U/L (9–67 U/L). His urinary calcium level is less than 3.0 mg/dL.

Urinalysis:

- Urine protein 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- No urine crystals

- 3 to 5 coarse granular urine casts per high-power field

- No hematuria or pyuria.

Renal ultrasonography shows normal kidneys with no hydronephrosis.

Renal biopsy study demonstrates noncaseating granulomatous interstitial nephritis (Figure 1).

GRANULOMATOUS INTERSTITIAL NEPHRITIS

1. Based on the information above, what is the most likely cause of this patient’s kidney disease?

- Medication

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Infection

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a histologic diagnosis that is present in up to 1% of renal biopsies. It has been associated with medications, infections, sarcoidosis, crystal deposits, paraproteinemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis and also is seen in an idiopathic form.

Medicines implicated include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, NSAIDs, allopurinol, and diuretics.

Mycobacteria and fungi are the main infective causes and seem to be the main causative factor in cases of renal transplant.1 Granulomas are usually not found on kidney biopsy in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and that diagnosis is usually made by the presence of antiproteinase 3 antibodies.2

Sarcoidosis is the most likely diagnosis in this patient after excluding implicated medications, infection, and vasculitis and confirming the presence of granulomatous interstitial nephritis on renal biopsy.

SARCOIDOSIS: A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown cause, characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. It can involve any organ but most commonly the thoracic and peripheral lymph nodes.3,4 Involvement of the eyes and skin is also relatively common.

Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in more than 30% of cases of sarcoidosis, almost always with concomitant thoracic involvement.5,6 Isolated extrathoracic sarcoidosis is unusual, found in only 2% of patients in a sarcoidosis case-control study.5

Current theory suggests that sarcoidosis develops from a cell-mediated immune response triggered by one or more unidentified antigens in people with a genetic predisposition.7

Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all ages, most often adults ages 20 to 40; but more recently, it has increased in US adults over age 55.8 The condition is more prevalent in Northern Europe and Japan, and in blacks in the United States.7

HOW COMMON IS RENAL INVOLVEMENT IN SARCOIDOSIS?

2. What is the likelihood of finding clinically apparent renal involvement in a patient with sarcoidosis?

- Greater than 70%

- Greater than 50%

- Up to 50%

- Less than 10%

The prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is hard to determine due to differences in study design and patient populations included in the available reports, and because renal involvement may be silent for many years. Recent studies have reported impaired renal function in 0.7% to 9.7% of cases: eg, a case-control study of 736 patients reported clinically apparent renal involvement in 0.7% of patients,5 and in a series of 818 patients, the incidence was 1%.9 In earlier studies, depending on the diagnostic criteria, the incidence ranged from 1.1% to 9.7%.10

The prevalence of renal involvement may also be underestimated because it can be asymptomatic, and the number of granulomas may be so few that they are absent in a small biopsy specimen. A higher prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is reported from autopsy studies, although many cases remained clinically silent. These studies have reported renal noncaseating granulomas in 7% to 23% of sarcoidosis patients.11–13

PRESENTATION OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

3. What is the most common presentation in isolated renal sarcoidosis?

- Sterile pyuria

- Elevated urine eosinophils

- Renal insufficiency

- Painless hematuria

Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis include hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and impaired renal function.14 Renal involvement can occur during the course of existing sarcoidosis, at the time of first presentation, or even as the sole presentation of the disease.1,11,15 In patients with isolated renal sarcoidosis, the most common presentation is renal insufficiency.15,16

Two main pathways for nephron insult that have been validated are granulomatous infiltration of the renal interstitium and disordered calcium homeostasis.11,17 Though extremely rare, various types of glomerular disease, renal tubular defects, and renal vascular involvement such as renal artery granulomatous angiitis have been documented.18

Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is known to cause hypercalcemia by increasing calcium absorption secondary to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production from granulomas. Our patient’s case is unusual, as renal failure was the sole extrapulmonary manifestation of sarcoidosis without hypercalcemia.

In sarcoidosis, extrarenal production of 1-alpha-hydroxylase by activated macrophages inappropriately increases levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol). Subsequently, serum calcium levels are increased. Unlike its renal equivalent, granulomatous 1-alpha-hydroxylase evades the normal negative feedback of hypercalcemia, so that increased calcitriol levels are sustained, leading to hypercalcemia, often accompanied by hypercalciuria.19

Disruption of calcium homeostasis affects renal function through several mechanisms. Hypercalcemia promotes vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole, leading to a reduction in the GFR. Intracellular calcium overload can contribute to acute tubular necrosis and intratubular precipitation of calcium, leading to tubular obstruction. Hypercalciuria predisposes to nephrolithiasis and obstructive uropathy. Chronic hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, if untreated, cause progressive interstitial inflammation and deposition of calcium in the kidney parenchyma and tubules, resulting in nephrocalcinosis. In some cases, nephrocalcinosis leads to chronic kidney injury and renal dysfunction.

HISTOLOGIC FEATURES

4. What is the characteristic histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis?

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Minimal change disease

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis

- Immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the most typical histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis.4,20–22 However, interstitial nephritis without granulomas is found in up to one-third of patients with sarcoid interstitial nephritis.15,23

Patients with sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis usually present with elevated serum creatinine with or without mild proteinuria (< 1 g/24 hours).1,15,16 Advanced renal failure (stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease) is relatively common at the time of presentation.1,15,16 In the 2 largest case series of renal sarcoidosis to date, the mean presenting serum creatinine levels were 3.0 and 4.8 mg/dL.11,15 The most common clinical syndrome associated with sarcoidosis and granulomatous interstitial nephritis is chronic kidney disease with a decline in renal function, which if untreated can occur over weeks to months.21 Acute renal failure as an initial presentation is also well documented.15,24

Even though glomerular involvement in sarcoidosis is rare, different kinds of glomerulonephritis have been reported, including membranous glomerulonephritis, mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental sclerosis, and crescentic glomerulonephritis.25

DIAGNOSIS OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

5. How is renal sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- By exclusion

- Complete urine analysis and renal function assessment

- Renal biopsy

- Computed tomography

- Renal ultrasonography

The diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis is one of exclusion. Sarcoidosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of renal failure of unknown origin, especially if disordered calcium homeostasis is also present. If clinically suspected, diagnosis usually requires pathohistologic demonstration of typical granulomatous lesions in the kidneys or in one or more organ systems.26

In cases of sarcoidosis with granulomatous interstitial nephritis with isolated renal failure as a presenting feature, other causes of granulomatous interstitial nephritis must be ruled out. A number of drug reactions are associated with interstitial nephritis, most commonly with antibiotics, NSAIDs, and diuretics. Although granulomatous interstitial nephritis may develop as a reaction to some drugs, most cases of drug-induced interstitial nephritis do not involve granulomatous interstitial nephritis.

Other causes of granulomatous interstitial infiltrates include granulomatous infection by mycobacteria, fungi, or Brucella; foreign-body reaction such as cholesterol atheroemboli; heroin; lymphoma; or autoimmune disease such as tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or Crohn disease.27,28 The absence of characteristic kidney biopsy findings does not exclude the diagnosis because renal sarcoidosis can be focal and easily missed on biopsy.29

Urinary manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are usually not specific. In renal sarcoidosis with interstitial nephritis with or without granulomas, proteinuria is mild or absent, usually less than 1.0 g/day.11,15,16 Urine studies may show a “bland” sediment (ie, without red or white blood cells) or may show sterile pyuria or microscopic hematuria. In glomerular disease, more overt proteinuria or the presence of red blood cell casts is more typical.

Hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis are nonspecific abnormalities that may be present in patients with sarcoidosis. In this regard, an elevated urine calcium level may support the diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis.

Computed tomography and renal ultrasonography may aid in diagnosis by detecting nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis.

The serum ACE level is elevated in 55% to 60% of patients with sarcoidosis, but it may also be elevated in other granulomatous diseases or in chronic kidney disease from various causes.5 Therefore, considering its nonspecificity, the serum ACE level has a limited role in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.30 Using the ACE level as a marker for disease activity and response to treatment remains controversial because levels do not correlate with disease activity.5,11

TREATMENT OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

6. Which is a first-line therapy for renal sarcoidosis?

- Corticosteroids

- Azathioprine

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Infliximab

- Adalimumab

Treatment of impaired calcium homeostasis in sarcoidosis includes hydration; reducing intake of calcium, vitamin D, and oxalate; and limiting sun exposure.11,31 For more significant hypercalcemia (eg, serum calcium levels > 11 mg/dL) or nephrolithiasis, corticosteroid therapy is the first choice and should be implemented at the first sign of renal involvement. Corticosteroids inhibit the activity of 1-alpha-hydroxylase in macrophages, thereby reducing the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have been mentioned in the literature as alternatives to corticosteroids.32 But the effect of these agents is less predictable and is slower than treatment with corticosteroids. Ketoconazole has no effect on granuloma formation but corrects hypercalcemia by inhibiting calcitriol production, and can be used as an adjunct for treating hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria.

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis, including granulomatous interstitial nephritis and interstitial nephritis without granulomas. Most patients experience significant improvement in renal function. However, full recovery is rare, likely as a result of long-standing disease with some degree of already established irreversible renal injury.16

Corticosteroid dosage

There is no standard dosing protocol, but patients with impaired renal function due to biopsy-proven renal sarcoidosis should receive prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day, depending on the severity of the disease, in a single dose every morning.

The optimal dosing and duration of maintenance therapy are unknown. Based on studies to date, the initial dosing should be maintained for 4 weeks, after which it can be tapered by 5 mg each week down to a maintenance dosage of 5 to 10 mg/day.4

Patients with a poor response after 4 weeks tend to have a worse renal outcome and are more susceptible to relapse.15 Fortunately, relapse often responds to increased corticosteroid doses.11,15 In the case of relapse, the dose should be increased to the lowest effective dose and continued for 4 weeks, then tapered more gradually.

A total of 24 months of treatment seems necessary to be effective and to prevent relapse.15 Some authors have proposed a lifelong maintenance dose for patients with frequent relapses, and some propose it for all patients.4

Other agents

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-blocking agents. Considering the critical role TNF plays in granuloma formation, anti-TNF-alpha agents are useful in steroid-resistant sarcoidosis.33 A thorough workup is necessary before starting these agents because of the increased risk of serious infection, including reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Of the current TNF-blocking agents, infliximab is most often used in renal sarcoidosis.34 Experience with adalimumab is more limited, though promising results indicate it could be an alternative for patients who do not tolerate infliximab.35

Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate may also be used as a second-line agent if treatment with corticosteroids is not tolerated or does not control the disease. The evidence in support of these agents is limited. In small series, they have allowed sustainable control of renal function while reducing the steroid dose. Currently, these agents are used for patients resistant to corticosteroid therapy, who would otherwise need prolonged high-dose corticosteroid treatment, or who have corticosteroid intolerance; they allow a more effective steroid taper and maintenance of stable renal function.15,36

The data supporting a standardized treatment of renal sarcoidosis are limited. For steroid intolerance or resistance, cytotoxic drugs and selected anti-TNF-alpha agents, as mentioned above, have shown promise in improving or stabilizing serum creatinine levels. Further exploration is required as to which agent or combination is better at limiting the disease process with fewer adverse effects.

Our patient was initially treated with corticosteroids and was ultimately weaned to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day. He was followed as an outpatient and was started on mycophenolate mofetil in place of higher steroid doses. His renal function stabilized, but he was lost to follow-up after 2 years.

KEY POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly involves the lungs, skin, and reticuloendothelial system.

- Renal involvement in sarcoidosis is likely underestimated due to its often clinically silent nature and the possibility of missing typical granulomatous lesions in a small or less-than-optimal biopsy sample.

- Manifestations of renal sarcoidosis include disrupted calcium homeostasis, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and renal failure.

- Because the clinical and histopathologic manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are nonspecific, the diagnosis is one of exclusion. In patients with renal failure or with hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria of unknown cause, renal sarcoidosis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Patients with chronic sarcoidosis should also be screened for renal impairment.

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the classic histologic finding of renal sarcoidosis. Nonetheless, up to one-third of patients have interstitial nephritis without granulomas.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis. An initial dose of oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day should be maintained for 4 weeks and then gradually tapered to 5 to 10 mg/day for a total of 24 months. Some patients require lifelong therapy.

- Several immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents may be used in cases of corticosteroid intolerance or to aid in effective taper of corticosteroids.

A black 37-year-old man has gradually lost 100 lb (45 kg) over the past 2 years, and reports progressive fatigue and malaise as well. He has not noted swollen lymph nodes, fever, or night sweats. He denies dyspnea, cough, or chest pain. He has no skin rashes, and no dry or red eyes or visual changes. He reports no flank pain, dysuria, frank hematuria, foamy urine, decline in urine output, or difficulty voiding.

He has no history of significant medical conditions. He does not drink, smoke, or use recreational drugs. He is not taking any prescription medications and has not been using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combination analgesics. He does not have a family history of kidney disease.

Physical examination. He appears relaxed and comfortable. He does not have nasal polyps or signs of pharyngeal inflammation. He has no apparent lymphadenopathy. His breath sounds are normal without rales or wheezes. Cardiac examination reveals a regular rhythm, with no rub or murmurs. The abdomen is soft and nontender with no flank pain or groin tenderness. The skin is intact with no rash or nodules.

- Temperature 98.4ºF (36.9ºC)

- Blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg

- Heart rate 102 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 19 per minute

- Oxygen saturation 99% while breathing room air

- Weight 194 lb (88 kg)

- Body mass index 28 kg/m2.

Laboratory testing (Table 1) reveals severe renal insufficiency with anemia:

- Serum creatinine 9 mg/dL (reference range 0.5–1.2)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 8 mL/min/1.73m2 (using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation).

His serum calcium level is normal, but his serum phosphorus is 5.3 mg/dL (reference range 2.5–4.6), and his parathyroid hormone level is 317 pg/mL (12–88), consistent with hyperparathyroidism secondary to chronic kidney disease. His 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is less than 13 ng/mL (30–80), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is 129 U/L (9–67 U/L). His urinary calcium level is less than 3.0 mg/dL.

Urinalysis:

- Urine protein 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- No urine crystals

- 3 to 5 coarse granular urine casts per high-power field

- No hematuria or pyuria.

Renal ultrasonography shows normal kidneys with no hydronephrosis.

Renal biopsy study demonstrates noncaseating granulomatous interstitial nephritis (Figure 1).

GRANULOMATOUS INTERSTITIAL NEPHRITIS

1. Based on the information above, what is the most likely cause of this patient’s kidney disease?

- Medication

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Infection

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a histologic diagnosis that is present in up to 1% of renal biopsies. It has been associated with medications, infections, sarcoidosis, crystal deposits, paraproteinemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis and also is seen in an idiopathic form.

Medicines implicated include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, NSAIDs, allopurinol, and diuretics.

Mycobacteria and fungi are the main infective causes and seem to be the main causative factor in cases of renal transplant.1 Granulomas are usually not found on kidney biopsy in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and that diagnosis is usually made by the presence of antiproteinase 3 antibodies.2

Sarcoidosis is the most likely diagnosis in this patient after excluding implicated medications, infection, and vasculitis and confirming the presence of granulomatous interstitial nephritis on renal biopsy.

SARCOIDOSIS: A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown cause, characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. It can involve any organ but most commonly the thoracic and peripheral lymph nodes.3,4 Involvement of the eyes and skin is also relatively common.

Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in more than 30% of cases of sarcoidosis, almost always with concomitant thoracic involvement.5,6 Isolated extrathoracic sarcoidosis is unusual, found in only 2% of patients in a sarcoidosis case-control study.5

Current theory suggests that sarcoidosis develops from a cell-mediated immune response triggered by one or more unidentified antigens in people with a genetic predisposition.7

Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all ages, most often adults ages 20 to 40; but more recently, it has increased in US adults over age 55.8 The condition is more prevalent in Northern Europe and Japan, and in blacks in the United States.7

HOW COMMON IS RENAL INVOLVEMENT IN SARCOIDOSIS?

2. What is the likelihood of finding clinically apparent renal involvement in a patient with sarcoidosis?

- Greater than 70%

- Greater than 50%

- Up to 50%

- Less than 10%

The prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is hard to determine due to differences in study design and patient populations included in the available reports, and because renal involvement may be silent for many years. Recent studies have reported impaired renal function in 0.7% to 9.7% of cases: eg, a case-control study of 736 patients reported clinically apparent renal involvement in 0.7% of patients,5 and in a series of 818 patients, the incidence was 1%.9 In earlier studies, depending on the diagnostic criteria, the incidence ranged from 1.1% to 9.7%.10

The prevalence of renal involvement may also be underestimated because it can be asymptomatic, and the number of granulomas may be so few that they are absent in a small biopsy specimen. A higher prevalence of renal involvement in sarcoidosis is reported from autopsy studies, although many cases remained clinically silent. These studies have reported renal noncaseating granulomas in 7% to 23% of sarcoidosis patients.11–13

PRESENTATION OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

3. What is the most common presentation in isolated renal sarcoidosis?

- Sterile pyuria

- Elevated urine eosinophils

- Renal insufficiency

- Painless hematuria

Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis include hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and impaired renal function.14 Renal involvement can occur during the course of existing sarcoidosis, at the time of first presentation, or even as the sole presentation of the disease.1,11,15 In patients with isolated renal sarcoidosis, the most common presentation is renal insufficiency.15,16

Two main pathways for nephron insult that have been validated are granulomatous infiltration of the renal interstitium and disordered calcium homeostasis.11,17 Though extremely rare, various types of glomerular disease, renal tubular defects, and renal vascular involvement such as renal artery granulomatous angiitis have been documented.18

Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is known to cause hypercalcemia by increasing calcium absorption secondary to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production from granulomas. Our patient’s case is unusual, as renal failure was the sole extrapulmonary manifestation of sarcoidosis without hypercalcemia.

In sarcoidosis, extrarenal production of 1-alpha-hydroxylase by activated macrophages inappropriately increases levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol). Subsequently, serum calcium levels are increased. Unlike its renal equivalent, granulomatous 1-alpha-hydroxylase evades the normal negative feedback of hypercalcemia, so that increased calcitriol levels are sustained, leading to hypercalcemia, often accompanied by hypercalciuria.19

Disruption of calcium homeostasis affects renal function through several mechanisms. Hypercalcemia promotes vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole, leading to a reduction in the GFR. Intracellular calcium overload can contribute to acute tubular necrosis and intratubular precipitation of calcium, leading to tubular obstruction. Hypercalciuria predisposes to nephrolithiasis and obstructive uropathy. Chronic hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, if untreated, cause progressive interstitial inflammation and deposition of calcium in the kidney parenchyma and tubules, resulting in nephrocalcinosis. In some cases, nephrocalcinosis leads to chronic kidney injury and renal dysfunction.

HISTOLOGIC FEATURES

4. What is the characteristic histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis?

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Minimal change disease

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis

- Immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the most typical histologic feature of renal sarcoidosis.4,20–22 However, interstitial nephritis without granulomas is found in up to one-third of patients with sarcoid interstitial nephritis.15,23

Patients with sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis usually present with elevated serum creatinine with or without mild proteinuria (< 1 g/24 hours).1,15,16 Advanced renal failure (stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease) is relatively common at the time of presentation.1,15,16 In the 2 largest case series of renal sarcoidosis to date, the mean presenting serum creatinine levels were 3.0 and 4.8 mg/dL.11,15 The most common clinical syndrome associated with sarcoidosis and granulomatous interstitial nephritis is chronic kidney disease with a decline in renal function, which if untreated can occur over weeks to months.21 Acute renal failure as an initial presentation is also well documented.15,24

Even though glomerular involvement in sarcoidosis is rare, different kinds of glomerulonephritis have been reported, including membranous glomerulonephritis, mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental sclerosis, and crescentic glomerulonephritis.25

DIAGNOSIS OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

5. How is renal sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- By exclusion

- Complete urine analysis and renal function assessment

- Renal biopsy

- Computed tomography

- Renal ultrasonography

The diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis is one of exclusion. Sarcoidosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of renal failure of unknown origin, especially if disordered calcium homeostasis is also present. If clinically suspected, diagnosis usually requires pathohistologic demonstration of typical granulomatous lesions in the kidneys or in one or more organ systems.26

In cases of sarcoidosis with granulomatous interstitial nephritis with isolated renal failure as a presenting feature, other causes of granulomatous interstitial nephritis must be ruled out. A number of drug reactions are associated with interstitial nephritis, most commonly with antibiotics, NSAIDs, and diuretics. Although granulomatous interstitial nephritis may develop as a reaction to some drugs, most cases of drug-induced interstitial nephritis do not involve granulomatous interstitial nephritis.

Other causes of granulomatous interstitial infiltrates include granulomatous infection by mycobacteria, fungi, or Brucella; foreign-body reaction such as cholesterol atheroemboli; heroin; lymphoma; or autoimmune disease such as tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or Crohn disease.27,28 The absence of characteristic kidney biopsy findings does not exclude the diagnosis because renal sarcoidosis can be focal and easily missed on biopsy.29

Urinary manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are usually not specific. In renal sarcoidosis with interstitial nephritis with or without granulomas, proteinuria is mild or absent, usually less than 1.0 g/day.11,15,16 Urine studies may show a “bland” sediment (ie, without red or white blood cells) or may show sterile pyuria or microscopic hematuria. In glomerular disease, more overt proteinuria or the presence of red blood cell casts is more typical.

Hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis are nonspecific abnormalities that may be present in patients with sarcoidosis. In this regard, an elevated urine calcium level may support the diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis.

Computed tomography and renal ultrasonography may aid in diagnosis by detecting nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis.

The serum ACE level is elevated in 55% to 60% of patients with sarcoidosis, but it may also be elevated in other granulomatous diseases or in chronic kidney disease from various causes.5 Therefore, considering its nonspecificity, the serum ACE level has a limited role in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.30 Using the ACE level as a marker for disease activity and response to treatment remains controversial because levels do not correlate with disease activity.5,11

TREATMENT OF RENAL SARCOIDOSIS

6. Which is a first-line therapy for renal sarcoidosis?

- Corticosteroids

- Azathioprine

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Infliximab

- Adalimumab

Treatment of impaired calcium homeostasis in sarcoidosis includes hydration; reducing intake of calcium, vitamin D, and oxalate; and limiting sun exposure.11,31 For more significant hypercalcemia (eg, serum calcium levels > 11 mg/dL) or nephrolithiasis, corticosteroid therapy is the first choice and should be implemented at the first sign of renal involvement. Corticosteroids inhibit the activity of 1-alpha-hydroxylase in macrophages, thereby reducing the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have been mentioned in the literature as alternatives to corticosteroids.32 But the effect of these agents is less predictable and is slower than treatment with corticosteroids. Ketoconazole has no effect on granuloma formation but corrects hypercalcemia by inhibiting calcitriol production, and can be used as an adjunct for treating hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria.

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis, including granulomatous interstitial nephritis and interstitial nephritis without granulomas. Most patients experience significant improvement in renal function. However, full recovery is rare, likely as a result of long-standing disease with some degree of already established irreversible renal injury.16

Corticosteroid dosage

There is no standard dosing protocol, but patients with impaired renal function due to biopsy-proven renal sarcoidosis should receive prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day, depending on the severity of the disease, in a single dose every morning.

The optimal dosing and duration of maintenance therapy are unknown. Based on studies to date, the initial dosing should be maintained for 4 weeks, after which it can be tapered by 5 mg each week down to a maintenance dosage of 5 to 10 mg/day.4

Patients with a poor response after 4 weeks tend to have a worse renal outcome and are more susceptible to relapse.15 Fortunately, relapse often responds to increased corticosteroid doses.11,15 In the case of relapse, the dose should be increased to the lowest effective dose and continued for 4 weeks, then tapered more gradually.

A total of 24 months of treatment seems necessary to be effective and to prevent relapse.15 Some authors have proposed a lifelong maintenance dose for patients with frequent relapses, and some propose it for all patients.4

Other agents

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-blocking agents. Considering the critical role TNF plays in granuloma formation, anti-TNF-alpha agents are useful in steroid-resistant sarcoidosis.33 A thorough workup is necessary before starting these agents because of the increased risk of serious infection, including reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Of the current TNF-blocking agents, infliximab is most often used in renal sarcoidosis.34 Experience with adalimumab is more limited, though promising results indicate it could be an alternative for patients who do not tolerate infliximab.35

Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate may also be used as a second-line agent if treatment with corticosteroids is not tolerated or does not control the disease. The evidence in support of these agents is limited. In small series, they have allowed sustainable control of renal function while reducing the steroid dose. Currently, these agents are used for patients resistant to corticosteroid therapy, who would otherwise need prolonged high-dose corticosteroid treatment, or who have corticosteroid intolerance; they allow a more effective steroid taper and maintenance of stable renal function.15,36

The data supporting a standardized treatment of renal sarcoidosis are limited. For steroid intolerance or resistance, cytotoxic drugs and selected anti-TNF-alpha agents, as mentioned above, have shown promise in improving or stabilizing serum creatinine levels. Further exploration is required as to which agent or combination is better at limiting the disease process with fewer adverse effects.

Our patient was initially treated with corticosteroids and was ultimately weaned to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day. He was followed as an outpatient and was started on mycophenolate mofetil in place of higher steroid doses. His renal function stabilized, but he was lost to follow-up after 2 years.

KEY POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly involves the lungs, skin, and reticuloendothelial system.

- Renal involvement in sarcoidosis is likely underestimated due to its often clinically silent nature and the possibility of missing typical granulomatous lesions in a small or less-than-optimal biopsy sample.

- Manifestations of renal sarcoidosis include disrupted calcium homeostasis, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, and renal failure.

- Because the clinical and histopathologic manifestations of renal sarcoidosis are nonspecific, the diagnosis is one of exclusion. In patients with renal failure or with hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria of unknown cause, renal sarcoidosis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Patients with chronic sarcoidosis should also be screened for renal impairment.

- Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is the classic histologic finding of renal sarcoidosis. Nonetheless, up to one-third of patients have interstitial nephritis without granulomas.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for renal sarcoidosis. An initial dose of oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day should be maintained for 4 weeks and then gradually tapered to 5 to 10 mg/day for a total of 24 months. Some patients require lifelong therapy.

- Several immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents may be used in cases of corticosteroid intolerance or to aid in effective taper of corticosteroids.

- Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2:222–230.

- Lutalo PM, D'Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener's granulomatosis). J Autoimmun 2014; 48–49:94–98.

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1224–1234.

- Rajakariar R, Sharples EJ, Raftery MJ, Sheaff M, Yaqoob MM. Sarcoid tubulo-interstitial nephritis: long-term outcome and response to corticosteroid therapy. Kidney Int 2006; 70:165–169.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al; Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) research group. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1885–1889.

- Rizzato G, Palmieri G, Agrati AM, Zanussi C. The organ-specific extrapulmonary presentation of sarcoidosis: a frequent occurrence but a challenge to an early diagnosis. A 3-year-long prospective observational study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004; 21:119–126.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2153–2165.

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13:1244–1252.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med 1983; 52:525–533.

- Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE, Scott JH. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med 1963; 35:67–89.

- Berliner AR, Haas M, Choi MJ. Sarcoidosis: the nephrologist's perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:856–870.

- Longcope WT, Freiman DG. A study of sarcoidosis; based on a combined investigation of 160 cases including 30 autopsies from The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 1952; 31:1–132.

- Branson JH, Park JH. Sarcoidosis hepatic involvement: presentation of a case with fatal liver involvement; including autopsy findings and review of the evidence for sarcoid involvement of the liver as found in the literature. Ann Intern Med 1954; 40:111–145.

- Muther RS, McCarron DA, Bennett WM. Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141:643–645.

- Mahevas M, Lescure FX, Boffa JJ, et al. Renal sarcoidosis: clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentation and outcome in 47 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009; 88:98–106.

- Robson MG, Banerjee D, Hopster D, Cairns HS. Seven cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of extrarenal sarcoid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:280–284.

- Casella FJ, Allon M. The kidney in sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993; 3:1555–1562.

- Rafat C, Bobrie G, Chedid A, Nochy D, Hernigou A, Plouin PF. Sarcoidosis presenting as severe renin-dependent hypertension due to kidney vascular injury. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7:383–386.

- Reichel H, Koeffler HP, Barbers R, Norman AW. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by cultured alveolar macrophages from normal human donors and from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 65:1201–1209.

- Brause M, Magnusson K, Degenhardt S, Helmchen U, Grabensee B. Renal involvement in sarcoidosis—a report of 6 cases. Clin Nephrol 2002; 57:142–148.

- Hannedouche T, Grateau G, Noel LH, et al. Renal granulomatous sarcoidosis: report of six cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1990; 5:18–24.

- Kettritz R, Goebel U, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of sarcoidosis revisited. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:2690–2694.

- Bergner R, Hoffmann M, Waldherr R, Uppenkamp M. Frequency of kidney disease in chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003; 20:126–132.

- O’Riordan E, Willert RP, Reeve R, et al. Isolated sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis: review of five cases at one center. Clin Nephrol 2001; 55:297–302.

- Gobel U, Kettritz R, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of renal sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:616–623.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Bijol V, Mendez GP, Nose V, Rennke HG. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases from a single institution. Int J Surg Pathol 2006; 14:57–63.

- Mignon F, Mery JP, Mougenot B, Ronco P, Roland J, Morel-Maroger L. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 1984; 13:219–245.

- Shah R, Shidham G, Agarwal A, Albawardi A, Nadasdy T. Diagnostic utility of kidney biopsy in patients with sarcoidosis and acute kidney injury. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2011; 4:131–136.

- Studdy PR, Bird R. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis—its value in present clinical practice. Ann Clin Biochem 1989; 26:13–18.

- Demetriou ET, Pietras SM, Holick MF. Hypercalcemia and soft tissue calcification owing to sarcoidosis: the sunlight-cola connection. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25:1695–1699.

- Beegle SH, Barba K, Gobunsuy R, Judson MA. Current and emerging pharmacological treatments for sarcoidosis: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013; 7:325–338.

- Roberts SD, Wilkes DS, Burgett RA, Knox KS. Refractory sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Chest 2003; 124:2028–2031.

- Ahmed MM, Mubashir E, Dossabhoy NR. Isolated renal sarcoidosis: a rare presentation of a rare disease treated with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26:1346–1349.

- Gupta R, Beaudet L, Moore J, Mehta T. Treatment of sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis with adalimumab. NDT Plus 2009; 2:139–142.

- Moudgil A, Przygodzki RM, Kher KK. Successful steroid-sparing treatment of renal limited sarcoidosis with mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Nephrol 2006; 21:281–285.

- Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2:222–230.

- Lutalo PM, D'Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener's granulomatosis). J Autoimmun 2014; 48–49:94–98.

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1224–1234.

- Rajakariar R, Sharples EJ, Raftery MJ, Sheaff M, Yaqoob MM. Sarcoid tubulo-interstitial nephritis: long-term outcome and response to corticosteroid therapy. Kidney Int 2006; 70:165–169.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al; Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS) research group. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1885–1889.

- Rizzato G, Palmieri G, Agrati AM, Zanussi C. The organ-specific extrapulmonary presentation of sarcoidosis: a frequent occurrence but a challenge to an early diagnosis. A 3-year-long prospective observational study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004; 21:119–126.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2153–2165.

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13:1244–1252.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med 1983; 52:525–533.

- Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE, Scott JH. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med 1963; 35:67–89.

- Berliner AR, Haas M, Choi MJ. Sarcoidosis: the nephrologist's perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:856–870.

- Longcope WT, Freiman DG. A study of sarcoidosis; based on a combined investigation of 160 cases including 30 autopsies from The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 1952; 31:1–132.

- Branson JH, Park JH. Sarcoidosis hepatic involvement: presentation of a case with fatal liver involvement; including autopsy findings and review of the evidence for sarcoid involvement of the liver as found in the literature. Ann Intern Med 1954; 40:111–145.

- Muther RS, McCarron DA, Bennett WM. Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141:643–645.

- Mahevas M, Lescure FX, Boffa JJ, et al. Renal sarcoidosis: clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentation and outcome in 47 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009; 88:98–106.

- Robson MG, Banerjee D, Hopster D, Cairns HS. Seven cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of extrarenal sarcoid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:280–284.

- Casella FJ, Allon M. The kidney in sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993; 3:1555–1562.

- Rafat C, Bobrie G, Chedid A, Nochy D, Hernigou A, Plouin PF. Sarcoidosis presenting as severe renin-dependent hypertension due to kidney vascular injury. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7:383–386.

- Reichel H, Koeffler HP, Barbers R, Norman AW. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by cultured alveolar macrophages from normal human donors and from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 65:1201–1209.

- Brause M, Magnusson K, Degenhardt S, Helmchen U, Grabensee B. Renal involvement in sarcoidosis—a report of 6 cases. Clin Nephrol 2002; 57:142–148.

- Hannedouche T, Grateau G, Noel LH, et al. Renal granulomatous sarcoidosis: report of six cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1990; 5:18–24.

- Kettritz R, Goebel U, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of sarcoidosis revisited. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:2690–2694.

- Bergner R, Hoffmann M, Waldherr R, Uppenkamp M. Frequency of kidney disease in chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003; 20:126–132.

- O’Riordan E, Willert RP, Reeve R, et al. Isolated sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis: review of five cases at one center. Clin Nephrol 2001; 55:297–302.

- Gobel U, Kettritz R, Schneider W, Luft F. The protean face of renal sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:616–623.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Bijol V, Mendez GP, Nose V, Rennke HG. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases from a single institution. Int J Surg Pathol 2006; 14:57–63.

- Mignon F, Mery JP, Mougenot B, Ronco P, Roland J, Morel-Maroger L. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 1984; 13:219–245.

- Shah R, Shidham G, Agarwal A, Albawardi A, Nadasdy T. Diagnostic utility of kidney biopsy in patients with sarcoidosis and acute kidney injury. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2011; 4:131–136.

- Studdy PR, Bird R. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis—its value in present clinical practice. Ann Clin Biochem 1989; 26:13–18.

- Demetriou ET, Pietras SM, Holick MF. Hypercalcemia and soft tissue calcification owing to sarcoidosis: the sunlight-cola connection. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25:1695–1699.

- Beegle SH, Barba K, Gobunsuy R, Judson MA. Current and emerging pharmacological treatments for sarcoidosis: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013; 7:325–338.

- Roberts SD, Wilkes DS, Burgett RA, Knox KS. Refractory sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Chest 2003; 124:2028–2031.

- Ahmed MM, Mubashir E, Dossabhoy NR. Isolated renal sarcoidosis: a rare presentation of a rare disease treated with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26:1346–1349.

- Gupta R, Beaudet L, Moore J, Mehta T. Treatment of sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis with adalimumab. NDT Plus 2009; 2:139–142.

- Moudgil A, Przygodzki RM, Kher KK. Successful steroid-sparing treatment of renal limited sarcoidosis with mycophenolate mofetil. Pediatr Nephrol 2006; 21:281–285.