User login

Once a month, a "dream team" of community and hospital physicians and nurses meets at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. Their goal: To improve the transition out of the hospital for patients with heart failure. Their progress: Since the group’s first meeting in 2008, the hospital’s 30-day, all-cause readmission rates for heart failure have fallen from 27% to less than 19%, according to figures tracked by the Connecticut Hospital Association.

"That’s a significant drop and puts the hospital below the state average of 25%. "We’re pretty proud of that," said Dr. Jason Ryan, a cardiologist and codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the university.

Dr. Ryan attributes the "dream team’s" successes to intensive patient education in the hospital, a mandatory follow-up visit with a physician at 7 days after discharge, and better communication between clinicians in the hospital and those in the community.

But possibly the biggest factor in their success has been physician commitment to keeping patients with preventable readmissions out of the hospital.

In the UConn program, the cardiologists have made a point of getting patients immediate clinic appointments to evaluate whether they are having a minor issue that can be dealt with in an outpatient setting or if they have a more serious concern that requires readmission to the hospital.

"Some of our patients call us with complaints that I could easily over the phone say, ‘Well, you need to go to the emergency room for that,’ " Dr. Ryan said. "If you’ve got a group of physicians who are not interested in this work, it’s very easy to send people to the emergency room."

The UConn program could end up being a model for other hospitals that are looking to reduce their readmission rates for heart failure and acute myocardial infarction ahead of financial penalties coming down the pike this fall from the Medicare program.

But can hospitals that serve diverse communities meaningfully enact such programs and expect similar successes?

And what will be the impact of the penalties on safety net hospitals that lack the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems?

Even after the data are risk adjusted for their sicker patients, safety net hospitals could still end up with higher than average readmissions. If CMS penalizes them with lower reimbursements due to their excessive readmission rates, they could be left with even fewer resource to care for sicker patients.

Medicare Turns Up the Heat

Starting in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin cutting Medicare payments to hospitals whose acute MI and heart failure readmission rates are considered too high.

It’s still unclear exactly what the cutoff point will be. CMS will use readmission data from July 2008 through June 2011 to determine excessive rates and penalties for fiscal year 2013, which begins this October.

CMS is defining all-cause readmission as occurring when a patient is discharged from a hospital and then admitted to the same hospital or another acute care hospital within 30 days.

Recent, risk-adjusted data from CMS offer a glimpse of where the country is in terms of reducing readmission rates.

For acute MI, the national rate for 30-day all-cause readmissions has dropped slightly, going from 19.9% from 2006 through 2009 to 19.8% from 2007 through 2010. During the same time period, readmissions for heart failure rose slightly, creeping up from 24.5% to 24.8%.

The data show the similar trends for mortality during the two reporting periods. The acute MI rates fell from 16.2% to 15.9%, while heart failure mortality rose from 11.2% to 11.3%.

Blaming Length of Stay

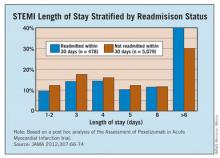

A study published earlier this year paints a gloomy picture about how U.S. hospitals stack up against other countries in readmission for ST-elevation MI. The study found that 30-day readmission rates were on average 14.5% in the United States vs. 9.9% among the other countries studied (JAMA 2012;307:66-74). The study included patients in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and 13 European countries.

At the same time, the median length of stay was shortest in the United States at 3 days. The longest median length of stay noted in the study was 8 days in Germany.

The study investigators pointed to the shorter length of stay in U.S. hospitals as a possible driver of the country’s higher rate of readmissions. But other experts say there are more complex factors at work, such as gaps in the discharge planning process and a lack of resources for patients once they leave the hospital.

There weren’t a lot of patients who were readmitted 2 days later for the same condition, which might indicate that they had been discharged too soon, Dr. Ryan said. More often, patients return to the hospital a week or several days later with a new problem. That tends to indicate that their medications may not have been adjusted correctly or that they were unable to access services in the outpatient world, he said.

There is very little evidence to support the idea that a longer initial length of stay would lead to either better use of evidence-based therapies or produce better clinical outcomes, said Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, director of the Cardiomyopathy Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Though there’s plenty of evidence to show that more time in the hospital increases patients’ risk for hospital-acquired infection, he added.

Over the last 2 decades, readmissions for heart failure patients have gone up as length of stay has decreased. But, Dr. Fonarow points out, during that same time the total number of days patients spent in the hospital has actually gone down, along with mortality. So from a global resource utilization perspective, patients are spending less time in the hospital and having better outcomes, he said.

"It’s important to have appropriate comparisons," he said.

Dr. Fonarow cautioned that there aren’t simple solutions to this problem. While there are many opportunities to improve readmission rates, there are also many rehospitalizations that are unavoidable or unrelated to the cardiovascular condition responsible for the initial hospitalization. Many patients hospitalized with acute MI, and to an even greater degree with heart failure, have multiple other cardiovascular and noncardiovascular comorbid conditions, he said.

"Efforts to try and reduce preventable readmissions have to go well beyond even the primary disease state that led to the hospitalization," Dr. Fonarow said. "They need to involve multiple components of care that go beyond just treating the single acute condition and focus on the multiple comorbid conditions that exist within that patient."

To make it even more complicated, patients who are hospitalized with heart failure tend to be older and to have multiple comorbid conditions. These individuals may face other challenges such as cognitive impairment, frailty, and poor socioeconomic support.

"It’s really a complex problem," he said.

Ensuring Needed Care

The looming Medicare readmission penalties have caused many hospital administrators, and in turn physicians, to look closely at the factors behind readmissions for the first time over the last few years.

"Everyone’s trying to figure this out because they do see the shift coming in the payment system," said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

And the payment cuts for excessive readmissions aren’t the only way that CMS is focusing on the issue, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Readmissions are also at the heart of pilot projects Medicare is launching for Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payments.

Dr. Rumsfeld said he’s concerned that physicians are getting the message that all readmissions are bad. "This is a potentially dangerous message for clinical care," he said.

The conversation needs to shift to unnecessary or potentially preventable readmissions, he said. It’s often underappreciated, Dr. Rumsfeld said, that patients who are having recurrent chest pain or severe shortness of breath after an acute MI should be admitted to the hospital for care. "There shouldn’t be anything in the system that disincentivizes that," he said.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, Chief of the Division of Cardiology at Northwestern University and Associate Director of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, agrees.

"We’re beating the drum about this problem mostly because it’s a health care utilization problem," Dr. Yancy said. "In the process of beating the drum, we have to have enough wherewithal as clinicians and administrators to realize that there are those – and not a small number – who should in fact be readmitted because their disease is unstable, or it’s advanced, or it requires that attention."

The fate of safety net hospitals is also a concern. Safety net hospitals are unlikely to have the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems, which could leave them with higher than average readmissions, even after the data is risk adjusted for their sicker patients, Dr. Yancy said. Then, if CMS cuts their reimbursement due to their excessive readmission rates, they will be left to care for sicker patients with even fewer resources.

"There has to be a point in this whole process where reasonable people sit back and look at how the landscape is truly impacted by this focus on readmissions," he said. "We can’t allow our safety net hospitals to be further disadvantaged."

Dr. Vincent Bufalino, Senior Vice President and Senior Medical Director of Cardiology at Advocate Health Care, a 100-physician cardiology group serving 10 hospitals in the Chicago area, said he thinks the readmission rates are a bit deceptive. While the numbers are high, especially in heart failure, these are also very sick patients, he said. "I’m not so disturbed with the readmission rate, although there are obviously opportunities for us to do better," Dr. Bufalino said.

One of those opportunities is in home health. Many heart failure and acute MI patients who could benefit from home health care after discharge aren’t getting it, he said, and it’s mostly because of a paperwork burden. Physicians aren’t making the referrals for home health because the paperwork required by CMS is so daunting.

While there are plenty of areas where physicians and hospitals can do a better job at care coordination, it’s important not to set unrealistic targets that force patients to be sent home when they should be admitted, Dr. Bufalino said.

"If someone is sick and they need to be readmitted, readmit them," he said.

Lessons Learned in Heart Failure

Physicians looking to make a dent in their readmission rates for heart failure can take some cues from successful programs around the country.

While the implementation varies from place to place, programs that have been able to cut their readmissions stress the need for patients to see a physician or nurse practitioner shortly after discharge. Another essential element for success is improving the communication between providers in the hospital and those who will be caring for patients after discharge.

At the University of Connecticut Heart Failure Center, where the all-cause 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients dropped from 27% in 2008 to under 19% in 2011, patients don’t leave the hospital without an appointment to see a physician within 7 days of discharge.

The appointment might be with a primary care physician, a cardiologist, or a physician or nurse practitioner at the university’s heart failure clinic.

"If we can’t get them in with someone else, we will always make room for them and see them," said Dr. Jason Ryan, codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

While patients are still in the hospital, they also meet with nurses who train them in taking their medications and monitoring for heart failure symptoms. Patients also meet with social workers who ensure they have transportation to their appointments and a way to pick up their medicines. And they spend time with a pharmacist who reviews their medications.

The other element they have employed at the University of Connecticut is community outreach. Before the push to reduce readmissions, physicians at the hospital didn’t know anyone at the nursing homes or visiting nurse organizations. Now they hold a monthly meeting with physicians and other providers who work outside the hospital. They have gone from not knowing each other’s names to exchanging cell phone numbers, Dr. Ryan said.

"So when our patients are out there we can communicate a lot more easily when problems crop up," he said.

At the University of California, San Francisco’s Medical Center, they have used similar strategies to cut their readmission rates.

The UCSF Heart Failure Readmission Reduction Program began in 2008 with a 2-year, $575,000 grant aimed at rapidly bringing down readmissions. Now in its fourth year, the nurse-run program has been a success. The 30-day all-cause readmission rates for heart failure patients age 65 and older was around 24% in 2009 but had dropped to less than 10% at the beginning of this year.

But the program couldn’t run without its two nurse coordinators, said Karen Rago, a nurse and executive director of Service Line Administration at UCSF.

"They own this population," she said. "If you don’t have a single point that owns it, there are so many things that fall through the cracks."

The nurses at the UCSF heart failure program spent the first year working with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to learn the principles in their readmissions toolkit: teach-back, follow-up phone calls at 7 and 14 days, an appointment with a physician or heart failure nurse practitioner within 7 days, and medication reconciliation.

The nurse coordinators also serve as a bridge to providers in the outpatient setting, Ms. Rago said. During the second year of the program, they began making site visits to skilled nursing facilities and reaching out to primary care physicians, cardiologists, and home health agencies from outside of the hospital.

They created an e-mail group for each patient’s care team that includes physicians, nurses, home care, social work, and pharmacy, depending on the services the patient needed. An email goes out to the team at the time of admission and it provides a way to update everyone virtually in real-time about the care of the patient.

Having a closer relationship with the skilled nursing facilities has been a big help, Ms. Rago said. During one of the site visits, the nurses discovered that one of the facilities didn’t offer a low-salt diet. That helped explain why so many patients from that facility were being readmitted to the hospital and they were able to quickly address it, she said.

What physicians need to keep in mind is that while many of these solutions are common sense, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to readmissions, said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

"It’s different in each community, so you can’t be prescriptive," he said.

The American College of Cardiology offers resources for reducing readmissions as part of a joint effort with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement called the Hospital to Home initiative.

Unlike other areas of care, such as getting a faster angioplasty, there aren’t six key steps for physicians to implement, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Instead, Hospital to Home is a place for physicians to share best practices based on their individual experiences. So far, more than 1,100 hospitals around the country have signed up.

Once a month, a "dream team" of community and hospital physicians and nurses meets at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. Their goal: To improve the transition out of the hospital for patients with heart failure. Their progress: Since the group’s first meeting in 2008, the hospital’s 30-day, all-cause readmission rates for heart failure have fallen from 27% to less than 19%, according to figures tracked by the Connecticut Hospital Association.

"That’s a significant drop and puts the hospital below the state average of 25%. "We’re pretty proud of that," said Dr. Jason Ryan, a cardiologist and codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the university.

Dr. Ryan attributes the "dream team’s" successes to intensive patient education in the hospital, a mandatory follow-up visit with a physician at 7 days after discharge, and better communication between clinicians in the hospital and those in the community.

But possibly the biggest factor in their success has been physician commitment to keeping patients with preventable readmissions out of the hospital.

In the UConn program, the cardiologists have made a point of getting patients immediate clinic appointments to evaluate whether they are having a minor issue that can be dealt with in an outpatient setting or if they have a more serious concern that requires readmission to the hospital.

"Some of our patients call us with complaints that I could easily over the phone say, ‘Well, you need to go to the emergency room for that,’ " Dr. Ryan said. "If you’ve got a group of physicians who are not interested in this work, it’s very easy to send people to the emergency room."

The UConn program could end up being a model for other hospitals that are looking to reduce their readmission rates for heart failure and acute myocardial infarction ahead of financial penalties coming down the pike this fall from the Medicare program.

But can hospitals that serve diverse communities meaningfully enact such programs and expect similar successes?

And what will be the impact of the penalties on safety net hospitals that lack the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems?

Even after the data are risk adjusted for their sicker patients, safety net hospitals could still end up with higher than average readmissions. If CMS penalizes them with lower reimbursements due to their excessive readmission rates, they could be left with even fewer resource to care for sicker patients.

Medicare Turns Up the Heat

Starting in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin cutting Medicare payments to hospitals whose acute MI and heart failure readmission rates are considered too high.

It’s still unclear exactly what the cutoff point will be. CMS will use readmission data from July 2008 through June 2011 to determine excessive rates and penalties for fiscal year 2013, which begins this October.

CMS is defining all-cause readmission as occurring when a patient is discharged from a hospital and then admitted to the same hospital or another acute care hospital within 30 days.

Recent, risk-adjusted data from CMS offer a glimpse of where the country is in terms of reducing readmission rates.

For acute MI, the national rate for 30-day all-cause readmissions has dropped slightly, going from 19.9% from 2006 through 2009 to 19.8% from 2007 through 2010. During the same time period, readmissions for heart failure rose slightly, creeping up from 24.5% to 24.8%.

The data show the similar trends for mortality during the two reporting periods. The acute MI rates fell from 16.2% to 15.9%, while heart failure mortality rose from 11.2% to 11.3%.

Blaming Length of Stay

A study published earlier this year paints a gloomy picture about how U.S. hospitals stack up against other countries in readmission for ST-elevation MI. The study found that 30-day readmission rates were on average 14.5% in the United States vs. 9.9% among the other countries studied (JAMA 2012;307:66-74). The study included patients in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and 13 European countries.

At the same time, the median length of stay was shortest in the United States at 3 days. The longest median length of stay noted in the study was 8 days in Germany.

The study investigators pointed to the shorter length of stay in U.S. hospitals as a possible driver of the country’s higher rate of readmissions. But other experts say there are more complex factors at work, such as gaps in the discharge planning process and a lack of resources for patients once they leave the hospital.

There weren’t a lot of patients who were readmitted 2 days later for the same condition, which might indicate that they had been discharged too soon, Dr. Ryan said. More often, patients return to the hospital a week or several days later with a new problem. That tends to indicate that their medications may not have been adjusted correctly or that they were unable to access services in the outpatient world, he said.

There is very little evidence to support the idea that a longer initial length of stay would lead to either better use of evidence-based therapies or produce better clinical outcomes, said Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, director of the Cardiomyopathy Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Though there’s plenty of evidence to show that more time in the hospital increases patients’ risk for hospital-acquired infection, he added.

Over the last 2 decades, readmissions for heart failure patients have gone up as length of stay has decreased. But, Dr. Fonarow points out, during that same time the total number of days patients spent in the hospital has actually gone down, along with mortality. So from a global resource utilization perspective, patients are spending less time in the hospital and having better outcomes, he said.

"It’s important to have appropriate comparisons," he said.

Dr. Fonarow cautioned that there aren’t simple solutions to this problem. While there are many opportunities to improve readmission rates, there are also many rehospitalizations that are unavoidable or unrelated to the cardiovascular condition responsible for the initial hospitalization. Many patients hospitalized with acute MI, and to an even greater degree with heart failure, have multiple other cardiovascular and noncardiovascular comorbid conditions, he said.

"Efforts to try and reduce preventable readmissions have to go well beyond even the primary disease state that led to the hospitalization," Dr. Fonarow said. "They need to involve multiple components of care that go beyond just treating the single acute condition and focus on the multiple comorbid conditions that exist within that patient."

To make it even more complicated, patients who are hospitalized with heart failure tend to be older and to have multiple comorbid conditions. These individuals may face other challenges such as cognitive impairment, frailty, and poor socioeconomic support.

"It’s really a complex problem," he said.

Ensuring Needed Care

The looming Medicare readmission penalties have caused many hospital administrators, and in turn physicians, to look closely at the factors behind readmissions for the first time over the last few years.

"Everyone’s trying to figure this out because they do see the shift coming in the payment system," said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

And the payment cuts for excessive readmissions aren’t the only way that CMS is focusing on the issue, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Readmissions are also at the heart of pilot projects Medicare is launching for Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payments.

Dr. Rumsfeld said he’s concerned that physicians are getting the message that all readmissions are bad. "This is a potentially dangerous message for clinical care," he said.

The conversation needs to shift to unnecessary or potentially preventable readmissions, he said. It’s often underappreciated, Dr. Rumsfeld said, that patients who are having recurrent chest pain or severe shortness of breath after an acute MI should be admitted to the hospital for care. "There shouldn’t be anything in the system that disincentivizes that," he said.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, Chief of the Division of Cardiology at Northwestern University and Associate Director of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, agrees.

"We’re beating the drum about this problem mostly because it’s a health care utilization problem," Dr. Yancy said. "In the process of beating the drum, we have to have enough wherewithal as clinicians and administrators to realize that there are those – and not a small number – who should in fact be readmitted because their disease is unstable, or it’s advanced, or it requires that attention."

The fate of safety net hospitals is also a concern. Safety net hospitals are unlikely to have the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems, which could leave them with higher than average readmissions, even after the data is risk adjusted for their sicker patients, Dr. Yancy said. Then, if CMS cuts their reimbursement due to their excessive readmission rates, they will be left to care for sicker patients with even fewer resources.

"There has to be a point in this whole process where reasonable people sit back and look at how the landscape is truly impacted by this focus on readmissions," he said. "We can’t allow our safety net hospitals to be further disadvantaged."

Dr. Vincent Bufalino, Senior Vice President and Senior Medical Director of Cardiology at Advocate Health Care, a 100-physician cardiology group serving 10 hospitals in the Chicago area, said he thinks the readmission rates are a bit deceptive. While the numbers are high, especially in heart failure, these are also very sick patients, he said. "I’m not so disturbed with the readmission rate, although there are obviously opportunities for us to do better," Dr. Bufalino said.

One of those opportunities is in home health. Many heart failure and acute MI patients who could benefit from home health care after discharge aren’t getting it, he said, and it’s mostly because of a paperwork burden. Physicians aren’t making the referrals for home health because the paperwork required by CMS is so daunting.

While there are plenty of areas where physicians and hospitals can do a better job at care coordination, it’s important not to set unrealistic targets that force patients to be sent home when they should be admitted, Dr. Bufalino said.

"If someone is sick and they need to be readmitted, readmit them," he said.

Lessons Learned in Heart Failure

Physicians looking to make a dent in their readmission rates for heart failure can take some cues from successful programs around the country.

While the implementation varies from place to place, programs that have been able to cut their readmissions stress the need for patients to see a physician or nurse practitioner shortly after discharge. Another essential element for success is improving the communication between providers in the hospital and those who will be caring for patients after discharge.

At the University of Connecticut Heart Failure Center, where the all-cause 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients dropped from 27% in 2008 to under 19% in 2011, patients don’t leave the hospital without an appointment to see a physician within 7 days of discharge.

The appointment might be with a primary care physician, a cardiologist, or a physician or nurse practitioner at the university’s heart failure clinic.

"If we can’t get them in with someone else, we will always make room for them and see them," said Dr. Jason Ryan, codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

While patients are still in the hospital, they also meet with nurses who train them in taking their medications and monitoring for heart failure symptoms. Patients also meet with social workers who ensure they have transportation to their appointments and a way to pick up their medicines. And they spend time with a pharmacist who reviews their medications.

The other element they have employed at the University of Connecticut is community outreach. Before the push to reduce readmissions, physicians at the hospital didn’t know anyone at the nursing homes or visiting nurse organizations. Now they hold a monthly meeting with physicians and other providers who work outside the hospital. They have gone from not knowing each other’s names to exchanging cell phone numbers, Dr. Ryan said.

"So when our patients are out there we can communicate a lot more easily when problems crop up," he said.

At the University of California, San Francisco’s Medical Center, they have used similar strategies to cut their readmission rates.

The UCSF Heart Failure Readmission Reduction Program began in 2008 with a 2-year, $575,000 grant aimed at rapidly bringing down readmissions. Now in its fourth year, the nurse-run program has been a success. The 30-day all-cause readmission rates for heart failure patients age 65 and older was around 24% in 2009 but had dropped to less than 10% at the beginning of this year.

But the program couldn’t run without its two nurse coordinators, said Karen Rago, a nurse and executive director of Service Line Administration at UCSF.

"They own this population," she said. "If you don’t have a single point that owns it, there are so many things that fall through the cracks."

The nurses at the UCSF heart failure program spent the first year working with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to learn the principles in their readmissions toolkit: teach-back, follow-up phone calls at 7 and 14 days, an appointment with a physician or heart failure nurse practitioner within 7 days, and medication reconciliation.

The nurse coordinators also serve as a bridge to providers in the outpatient setting, Ms. Rago said. During the second year of the program, they began making site visits to skilled nursing facilities and reaching out to primary care physicians, cardiologists, and home health agencies from outside of the hospital.

They created an e-mail group for each patient’s care team that includes physicians, nurses, home care, social work, and pharmacy, depending on the services the patient needed. An email goes out to the team at the time of admission and it provides a way to update everyone virtually in real-time about the care of the patient.

Having a closer relationship with the skilled nursing facilities has been a big help, Ms. Rago said. During one of the site visits, the nurses discovered that one of the facilities didn’t offer a low-salt diet. That helped explain why so many patients from that facility were being readmitted to the hospital and they were able to quickly address it, she said.

What physicians need to keep in mind is that while many of these solutions are common sense, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to readmissions, said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

"It’s different in each community, so you can’t be prescriptive," he said.

The American College of Cardiology offers resources for reducing readmissions as part of a joint effort with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement called the Hospital to Home initiative.

Unlike other areas of care, such as getting a faster angioplasty, there aren’t six key steps for physicians to implement, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Instead, Hospital to Home is a place for physicians to share best practices based on their individual experiences. So far, more than 1,100 hospitals around the country have signed up.

Once a month, a "dream team" of community and hospital physicians and nurses meets at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. Their goal: To improve the transition out of the hospital for patients with heart failure. Their progress: Since the group’s first meeting in 2008, the hospital’s 30-day, all-cause readmission rates for heart failure have fallen from 27% to less than 19%, according to figures tracked by the Connecticut Hospital Association.

"That’s a significant drop and puts the hospital below the state average of 25%. "We’re pretty proud of that," said Dr. Jason Ryan, a cardiologist and codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the university.

Dr. Ryan attributes the "dream team’s" successes to intensive patient education in the hospital, a mandatory follow-up visit with a physician at 7 days after discharge, and better communication between clinicians in the hospital and those in the community.

But possibly the biggest factor in their success has been physician commitment to keeping patients with preventable readmissions out of the hospital.

In the UConn program, the cardiologists have made a point of getting patients immediate clinic appointments to evaluate whether they are having a minor issue that can be dealt with in an outpatient setting or if they have a more serious concern that requires readmission to the hospital.

"Some of our patients call us with complaints that I could easily over the phone say, ‘Well, you need to go to the emergency room for that,’ " Dr. Ryan said. "If you’ve got a group of physicians who are not interested in this work, it’s very easy to send people to the emergency room."

The UConn program could end up being a model for other hospitals that are looking to reduce their readmission rates for heart failure and acute myocardial infarction ahead of financial penalties coming down the pike this fall from the Medicare program.

But can hospitals that serve diverse communities meaningfully enact such programs and expect similar successes?

And what will be the impact of the penalties on safety net hospitals that lack the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems?

Even after the data are risk adjusted for their sicker patients, safety net hospitals could still end up with higher than average readmissions. If CMS penalizes them with lower reimbursements due to their excessive readmission rates, they could be left with even fewer resource to care for sicker patients.

Medicare Turns Up the Heat

Starting in October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin cutting Medicare payments to hospitals whose acute MI and heart failure readmission rates are considered too high.

It’s still unclear exactly what the cutoff point will be. CMS will use readmission data from July 2008 through June 2011 to determine excessive rates and penalties for fiscal year 2013, which begins this October.

CMS is defining all-cause readmission as occurring when a patient is discharged from a hospital and then admitted to the same hospital or another acute care hospital within 30 days.

Recent, risk-adjusted data from CMS offer a glimpse of where the country is in terms of reducing readmission rates.

For acute MI, the national rate for 30-day all-cause readmissions has dropped slightly, going from 19.9% from 2006 through 2009 to 19.8% from 2007 through 2010. During the same time period, readmissions for heart failure rose slightly, creeping up from 24.5% to 24.8%.

The data show the similar trends for mortality during the two reporting periods. The acute MI rates fell from 16.2% to 15.9%, while heart failure mortality rose from 11.2% to 11.3%.

Blaming Length of Stay

A study published earlier this year paints a gloomy picture about how U.S. hospitals stack up against other countries in readmission for ST-elevation MI. The study found that 30-day readmission rates were on average 14.5% in the United States vs. 9.9% among the other countries studied (JAMA 2012;307:66-74). The study included patients in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and 13 European countries.

At the same time, the median length of stay was shortest in the United States at 3 days. The longest median length of stay noted in the study was 8 days in Germany.

The study investigators pointed to the shorter length of stay in U.S. hospitals as a possible driver of the country’s higher rate of readmissions. But other experts say there are more complex factors at work, such as gaps in the discharge planning process and a lack of resources for patients once they leave the hospital.

There weren’t a lot of patients who were readmitted 2 days later for the same condition, which might indicate that they had been discharged too soon, Dr. Ryan said. More often, patients return to the hospital a week or several days later with a new problem. That tends to indicate that their medications may not have been adjusted correctly or that they were unable to access services in the outpatient world, he said.

There is very little evidence to support the idea that a longer initial length of stay would lead to either better use of evidence-based therapies or produce better clinical outcomes, said Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, director of the Cardiomyopathy Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Though there’s plenty of evidence to show that more time in the hospital increases patients’ risk for hospital-acquired infection, he added.

Over the last 2 decades, readmissions for heart failure patients have gone up as length of stay has decreased. But, Dr. Fonarow points out, during that same time the total number of days patients spent in the hospital has actually gone down, along with mortality. So from a global resource utilization perspective, patients are spending less time in the hospital and having better outcomes, he said.

"It’s important to have appropriate comparisons," he said.

Dr. Fonarow cautioned that there aren’t simple solutions to this problem. While there are many opportunities to improve readmission rates, there are also many rehospitalizations that are unavoidable or unrelated to the cardiovascular condition responsible for the initial hospitalization. Many patients hospitalized with acute MI, and to an even greater degree with heart failure, have multiple other cardiovascular and noncardiovascular comorbid conditions, he said.

"Efforts to try and reduce preventable readmissions have to go well beyond even the primary disease state that led to the hospitalization," Dr. Fonarow said. "They need to involve multiple components of care that go beyond just treating the single acute condition and focus on the multiple comorbid conditions that exist within that patient."

To make it even more complicated, patients who are hospitalized with heart failure tend to be older and to have multiple comorbid conditions. These individuals may face other challenges such as cognitive impairment, frailty, and poor socioeconomic support.

"It’s really a complex problem," he said.

Ensuring Needed Care

The looming Medicare readmission penalties have caused many hospital administrators, and in turn physicians, to look closely at the factors behind readmissions for the first time over the last few years.

"Everyone’s trying to figure this out because they do see the shift coming in the payment system," said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

And the payment cuts for excessive readmissions aren’t the only way that CMS is focusing on the issue, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Readmissions are also at the heart of pilot projects Medicare is launching for Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payments.

Dr. Rumsfeld said he’s concerned that physicians are getting the message that all readmissions are bad. "This is a potentially dangerous message for clinical care," he said.

The conversation needs to shift to unnecessary or potentially preventable readmissions, he said. It’s often underappreciated, Dr. Rumsfeld said, that patients who are having recurrent chest pain or severe shortness of breath after an acute MI should be admitted to the hospital for care. "There shouldn’t be anything in the system that disincentivizes that," he said.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, Chief of the Division of Cardiology at Northwestern University and Associate Director of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, agrees.

"We’re beating the drum about this problem mostly because it’s a health care utilization problem," Dr. Yancy said. "In the process of beating the drum, we have to have enough wherewithal as clinicians and administrators to realize that there are those – and not a small number – who should in fact be readmitted because their disease is unstable, or it’s advanced, or it requires that attention."

The fate of safety net hospitals is also a concern. Safety net hospitals are unlikely to have the money to undertake a major overhaul of their discharge and care coordination systems, which could leave them with higher than average readmissions, even after the data is risk adjusted for their sicker patients, Dr. Yancy said. Then, if CMS cuts their reimbursement due to their excessive readmission rates, they will be left to care for sicker patients with even fewer resources.

"There has to be a point in this whole process where reasonable people sit back and look at how the landscape is truly impacted by this focus on readmissions," he said. "We can’t allow our safety net hospitals to be further disadvantaged."

Dr. Vincent Bufalino, Senior Vice President and Senior Medical Director of Cardiology at Advocate Health Care, a 100-physician cardiology group serving 10 hospitals in the Chicago area, said he thinks the readmission rates are a bit deceptive. While the numbers are high, especially in heart failure, these are also very sick patients, he said. "I’m not so disturbed with the readmission rate, although there are obviously opportunities for us to do better," Dr. Bufalino said.

One of those opportunities is in home health. Many heart failure and acute MI patients who could benefit from home health care after discharge aren’t getting it, he said, and it’s mostly because of a paperwork burden. Physicians aren’t making the referrals for home health because the paperwork required by CMS is so daunting.

While there are plenty of areas where physicians and hospitals can do a better job at care coordination, it’s important not to set unrealistic targets that force patients to be sent home when they should be admitted, Dr. Bufalino said.

"If someone is sick and they need to be readmitted, readmit them," he said.

Lessons Learned in Heart Failure

Physicians looking to make a dent in their readmission rates for heart failure can take some cues from successful programs around the country.

While the implementation varies from place to place, programs that have been able to cut their readmissions stress the need for patients to see a physician or nurse practitioner shortly after discharge. Another essential element for success is improving the communication between providers in the hospital and those who will be caring for patients after discharge.

At the University of Connecticut Heart Failure Center, where the all-cause 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients dropped from 27% in 2008 to under 19% in 2011, patients don’t leave the hospital without an appointment to see a physician within 7 days of discharge.

The appointment might be with a primary care physician, a cardiologist, or a physician or nurse practitioner at the university’s heart failure clinic.

"If we can’t get them in with someone else, we will always make room for them and see them," said Dr. Jason Ryan, codirector of the Heart Failure Center at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

While patients are still in the hospital, they also meet with nurses who train them in taking their medications and monitoring for heart failure symptoms. Patients also meet with social workers who ensure they have transportation to their appointments and a way to pick up their medicines. And they spend time with a pharmacist who reviews their medications.

The other element they have employed at the University of Connecticut is community outreach. Before the push to reduce readmissions, physicians at the hospital didn’t know anyone at the nursing homes or visiting nurse organizations. Now they hold a monthly meeting with physicians and other providers who work outside the hospital. They have gone from not knowing each other’s names to exchanging cell phone numbers, Dr. Ryan said.

"So when our patients are out there we can communicate a lot more easily when problems crop up," he said.

At the University of California, San Francisco’s Medical Center, they have used similar strategies to cut their readmission rates.

The UCSF Heart Failure Readmission Reduction Program began in 2008 with a 2-year, $575,000 grant aimed at rapidly bringing down readmissions. Now in its fourth year, the nurse-run program has been a success. The 30-day all-cause readmission rates for heart failure patients age 65 and older was around 24% in 2009 but had dropped to less than 10% at the beginning of this year.

But the program couldn’t run without its two nurse coordinators, said Karen Rago, a nurse and executive director of Service Line Administration at UCSF.

"They own this population," she said. "If you don’t have a single point that owns it, there are so many things that fall through the cracks."

The nurses at the UCSF heart failure program spent the first year working with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to learn the principles in their readmissions toolkit: teach-back, follow-up phone calls at 7 and 14 days, an appointment with a physician or heart failure nurse practitioner within 7 days, and medication reconciliation.

The nurse coordinators also serve as a bridge to providers in the outpatient setting, Ms. Rago said. During the second year of the program, they began making site visits to skilled nursing facilities and reaching out to primary care physicians, cardiologists, and home health agencies from outside of the hospital.

They created an e-mail group for each patient’s care team that includes physicians, nurses, home care, social work, and pharmacy, depending on the services the patient needed. An email goes out to the team at the time of admission and it provides a way to update everyone virtually in real-time about the care of the patient.

Having a closer relationship with the skilled nursing facilities has been a big help, Ms. Rago said. During one of the site visits, the nurses discovered that one of the facilities didn’t offer a low-salt diet. That helped explain why so many patients from that facility were being readmitted to the hospital and they were able to quickly address it, she said.

What physicians need to keep in mind is that while many of these solutions are common sense, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to readmissions, said Dr. John Rumsfeld, National Director of Cardiology at the Veterans Health Administration and Chief Science Officer for the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

"It’s different in each community, so you can’t be prescriptive," he said.

The American College of Cardiology offers resources for reducing readmissions as part of a joint effort with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement called the Hospital to Home initiative.

Unlike other areas of care, such as getting a faster angioplasty, there aren’t six key steps for physicians to implement, Dr. Rumsfeld said. Instead, Hospital to Home is a place for physicians to share best practices based on their individual experiences. So far, more than 1,100 hospitals around the country have signed up.