With an increasing demand for mental health services for veterans in rural clinics, telehealth can deliver services to veterans at home or in other nonclinic settings. Telehealth can reduce demands on VA clinic space and staff required for traditional videoconferencing.

Clinic-based telemental health started at the VA in 2003 and has provided access to more than 1 million appointments.1 Despite the great strides in accessibility, logistic barriers limit expansion of clinic-based telehealth appointments. A VA staff member at the patient site must be available to “greet and seat” the veteran; scheduling requires 2 separate appointments (on patient and provider sites); and limited telehealth equipment and clinic space need to be reserved ahead of time.

The first known use of telehealth technologies to deliver mental health services within the VA network information technology system to at-home veterans occurred in 2009 at the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPORHCS) in Oregon. Between 2010 and 2013, the VAPORHCS Home-Based Telemental Health (HBTMH) pilot served about 82 veterans through about 740 appointments. The HBTMH pilot transitioned from a single facility to a regional implementation model under an Office of Innovation Grant Innovation #669: Home-Based Telemental Health (Innovation), which served about 84 veterans from 2013 to 2014.

In 2014, about 4,200 veterans accessed some health care via the national Clinical Video Telehealth–Into the Home (CVT-IH) program, with all 21 VISNs participating (John Peters, e-mail communication, February 2014). In all 3 implementation models (HBTMH pilot, Innovation, and CVT-IH), the veteran can receive health services via videoconferencing in real time, on personal or loaned computers, at home or in another nonclinic setting.

As the VA’s use of telehealth services grows in non-VA settings, technical support remains a significant challenge.2 Increased use of CVT-IH through veterans’ personal computers and devices has generated a corresponding need for technical support. The National Telehealth Technical Help Desk (NTTHD), which supports the national CVT-IH program, does not provide technical support directly to veterans. Instead, recommendations are given to the providers who are expected to transmit and implement the technical solutions with the veterans. Similarly, HBTMH pilot providers were initially responsible for all technical issues for home-based telehealth work, including helping patients with software installation and subsequent troubleshooting.

Providers participating in the HBTMH pilot project encountered veterans with all levels of comfort and skill with the required technology. Some veterans have never used a personal computer, e-mail, and/or webcam. Addressing technical issues often required up to 15 to 20 minutes during an HBTMH pilot session; some cases took hours spread over several days. In VISN 20, providers in Oregon and Washington have reported discontinuation of treatment of veterans enrolled in CVT-IH for technical reasons, including poor connections, lack of timely technical support, and incompatibility of veteran-owned computers with VA-approved third-party software (Anders Goranson, Sara Smucker Barnwell, Kathleen Woodside, e-mail communication, December 2013).

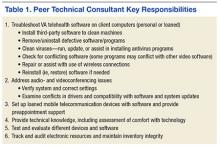

A peer technical consultant (PTC) who directly serves patients and providers may be better positioned to meet the technical needs of everyone involved in a home-based telehealth program. The PTC role was developed for the HBTMH Pilot and expanded during the Innovation program. The authors describe the role of the PTC, outline key responsibilities, and highlight how the PTC can provide effective technical support and improve provider and patient access and engagement with nonclinic-based telehealth services.

Methods

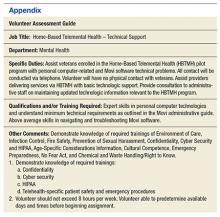

Lessons from the initial phases of the HBTMH pilot strongly suggested that technical barriers had to be reduced. In 2010, a former patient in the HBTMH pilot who had a background in information technology and computer systems and interest in helping other veterans contacted Dr. Peter Shore. They developed the novel role of a PTC, focused on delivering technical support with compassion (Table 1). A functional statement and position description were submitted to volunteer services at the VAPORHCS (Appendix). With the regionwide expansion of the HBTMH pilot into the Innovation program, the PTC was hired as a full-time contract employee to increase the availability of technical support.

The PTC assumed responsibility for installations and troubleshooting for both providers and veterans enrolled in the HBTMH pilot. The PTC, who was based at the VAPORHCS, received referrals, contacted veterans by telephone, addressed technical problems, and reported the result to the provider. No face-to-face contact occurred between the PTC and the veterans. The PTC received regular supervision from the project director. Starting in mid-2012, local providers who were using the national CVT-IH program also requested PTC services. The PTC was able to add technical support for veterans beyond the NTTHD model, allowing for immediate in-session attention in some cases.