On admission to the psychiatric service, the patient complained of body aches, chills, rhinorrhea, and significantly worsened irritability from his baseline. Initial point-of-care admission drug testing had been negative as had expanded urine tests looking for synthetic opioids, cannabinoids, and cathinones. The patient reported no opioid use but was unable to explain his current symptom patterns, which were worsening his chronic pain and hampering any attempt to build rapport. On hospital day 3, the patient’s additional sequelae had passed, and psychiatric treatment was able to progress fully. On hospital day 4, the inpatient treatment team received a message from the patient’s primary care manager stating that a friend of the patient had found a bottle of herbal pills in the patient’s car. This was later revealed to be a kratom formulation that he had purchased online.

Background

Kratom is the colloquial name of a tree that is native to Thailand, Malaysia, and other countries in Southeast Asia. These trees, which can grow to 50 feet high and 15 feet wide, have long been the source of herbal remedies in Southeast Asia (eFigure).2,3 The leaves contain psychoactive substances that have a variety of effects when consumed. At low doses, kratom causes a stimulant effect (akin to the leaves of the coca plant in South America); laborers and farmers often use it to help boost their energy. At higher doses, kratom causes an opioid-l

ike effect, which at mega doses produces an intense euphoric state and has led to a steady growth in abuse worldwide. Although the government of Thailand banned the planting of Mitragyna speciosa as early as 1943, its continued proliferation in Southeast Asia and throughout the world has not ceased.2,3,6In the United Kingdom, kratom is currently the second most common drug that is considered a legal high, only behind salvia (Salvia divinorum), a hallucinogenic herb that is better known as a result of its use by young celebrities over the past decade.5,8 Presently, kratom’s legal status in the U.S. continues to be nebulous: It has not been officially scheduled by the DEA, and it is easily obtained.

Kratom can be taken in a variety of ways: Crushed leaves often are placed in gel caps and swallowed; it can be drunk as a tea, juice, or boiled syrup; and it can be smoked or insufflated.2,3,5,6

Pharmacology and Clinical Presentation

More than 20 psychoactive compounds have been isolated from kratom. Although a discussion of all these compounds is beyond the scope of this review, the 2 major compounds are mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine.

Mitragynine

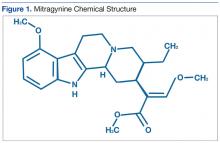

Mitragynine, the most abundant psychoactive compound found in kratom, is an indole alkaloid (Figure 1). Extraction and analysis of this compound has demonstrated numerous effects on multiple receptors, including μ, δ, and κ opioid receptors, leading to its opioid-like ef

fects, including analgesia and euphoria. Also similar to common opioids, withdrawal symptomatology can present after only 5 days of daily use. There is limited evidence that mitragynine can activate postsynaptic α-2 adrenergic receptors, which may act synergistically with the μ agonist with regard to its analgesic effect.2,57-Hydroxymitragynine

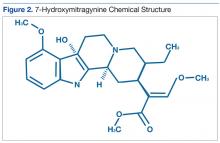

7-hydroxymitragynine, despite being far less concentrated in kratom preparations, is about 13 times more potent than morphine and 46 times more potent than mitragynine. It is thought that its hydroxyl side chain added to C7 (Figure 2) adds to its lipophilicity and ability to cross the blood-brain barrier at a far more rapid rate than that of mitragynine.2

Mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine remain the best-studied psychoactive components of kratom at this time. Other compounds that have been isolated, such as speciociliatine, paynantheine, and speciogynine, may play a role in kratom’s analgesic and psychoactive effects. Animal studies have demonstrated antimuscarinic properties in these compounds, but the properties do not seem to have any demonstrable effect at the opioid receptors.2

Intoxication and Withdrawal

Due to its increasing worldwide popularity, it is now imperative for HCPs to be aware of the clinical presentation of kratom abuse as well as the management of withdrawal in light of its dependence potential. However, large-scale studies have not been performed, and much of the evidence comes not from the medical literature but from prodrug websites like Erowid or SageWisdom.2,5-9 To that end, such information will be discussed along with the limited research and expert consensuses available in peer-reviewed medical literature.

Kratom seems to have dose-dependent effects. At low doses (1 g-5 g of raw crushed leaves), kratom abusers often report a mild energizing effect, thought to be secondary to the stimulant properties of kratom’s multiple alkaloids. Users have reported mild euphoria and highs similar to those of the abuse of methylphenidate or modafinil.2,9,10 Also similar to abuse of those substances, users have reported anxiety, irritability, and aggressiveness as a result of the stimulant-like effects.

At moderate-to-high doses (5 g-15 g of raw crushed leaves), it is believed that the μ opiate receptor agonism overtakes the stimulant effects, leading to the euphoria, relaxation, and analgesia seen with conventional opioid use and abuse.2,10 In light of the drug’s substantial binding and agonism of all opioid receptors, constipation and itching also are seen.2 As such, if an individual is intoxicated, he or she should be managed symptomatically with judicious use of benzodiazepines and continuous monitoring of heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation.2,10 Kratom intoxication can precipitate psychotic episodes similar to those caused by opiate intoxication, so monitoring for agitation or psychotic behaviors is also indicated.9,10

The medical management of an acute kratom overdose (typically requiring ingestion of > 15 g of crushed leaves) begins with addressing airway blockage, breathing, and circulation along with continuous vital sign monitoring and laboratory testing, including point-of-care glucose, complete blood count, electrolytes, lactate, venous blood gas, and measurable drug levels (ethanol, acetaminophen, tricyclic antidepressants, etc).11 If it is determined that kratom was the intoxicant, the greatest concern of death is similar to that of opioid overdose: respiratory depression. Although there are no large-scale human studies demonstrating efficacy, multiple authors suggest the use of naloxone in kratom-related hypoventilation.9,10

The development of dependence on kratom and its subsequent withdrawal phenomena are thought to be similar to that of opioids, in light of its strong μ agonism.2,5,9,10 Indeed, kratom has a long history of being used by opioid-dependent patients as an attempt to quit drug abuse or stave off debilitating withdrawal symptoms when they are unable to acquire their substance of choice.2,5-10 As such, withdrawal and the treatment thereof will also mimic that of opioid detoxification.

The kratom-dependent individual will often present with rhinorrhea, lacrimation, dry mouth, hostility, aggression, and emotional lability similar to the case study described earlier.2,9,10 Kratom withdrawal, much like intoxication, also may precipitate or worsen psychotic symptoms, and monitoring is necessary throughout the detoxification process.2,5,10 Withdrawal management should proceed along ambulatory clinic or hospital opioid withdrawal protocols that include step-down administration of opioids or with nonopioid medications for symptomatic relief, including muscle relaxants, α-2 agonists, and antidiarrheal agents.5,9,10