About 24% of women and 1% of men will experience military sexual trauma (MST) during their service.1 Despite the higher percentage of women reporting MST, the estimated number of men (55,491) and women (72,497) who endorse MST is relatively similar. Military sexual trauma is associated with negative psychosocial (eg, decreased quality of life) and psychiatric (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression) sequelae. Surís and colleagues provided a full review of sequelae, with PTSD being the most discussed consequence of MST.2 However, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during or after MST are a consequence of growing concern.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The link between sexual trauma and increased incidence of STIs is well established. Survivors of rape are at a higher risk of exposure to STIs due to unprotected sexual contact that may occur during the assault(s).3 Numerous studies have demonstrated that sexual trauma is directly related to greater engagement in risky sexual behaviors (eg, more sexual partners, unprotected sex, and “sex trading”).2,4

This relationship is particularly concerning given that individuals in the military tend to report sexual trauma with greater propensity than that reported in civilian populations.4 Additionally, military personnel and veteran populations tend to engage in high-risk behaviors (eg, alcohol and drug use) more often than their civilian counterparts, increasing their potential susceptibility to predatory sexual trauma(s) and victimization.2,5 Taken in aggregate, military personnel and veterans may be at increased risk for STIs compared with the civilian population due to the increased incidence of risky sexual behavior and sexual traumatization during military service.

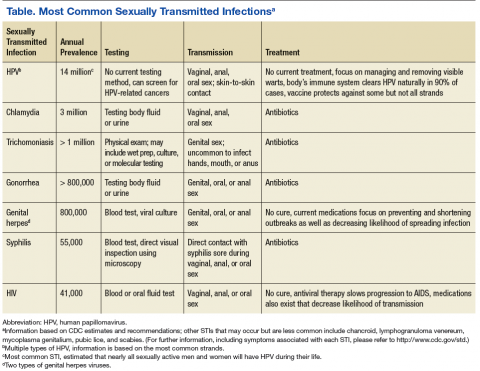

Sexually transmitted infections potentially lead to immediate-term (eg, physical discomfort, sexual dysfunction) and long-term (eg, cancer, infertility) adverse health consequences.6 Early detection is crucial in the treatment of STIs because it can aid in preventing STI transmission and allow for early intervention. See Table for a list of common STIs and their prevalence, testing method, method of sexual transmission, and treatment. Early detection is also important because many STIs may be asymptomatic (eg, HIV, human papillomavirus [HPV]), which decreases the likelihood of seeking testing or treatment as well as increases the likelihood of transmission.7

Current Research

To date, only 1 study has explicitly examined the relationship between MST and STIs. In 2011, researchers analyzed a large national database of 420,725 male and female Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans.6 In the study, both male and female OEF/OIF veterans who endorsed MST were significantly more likely than those who did not endorse MST to have a STI diagnosis. The researchers noted that this finding underscored the necessity for sexual health assessment in survivors of MST, to facilitate early detection and treatment.

STI Risk Assessment

Because military personnel and veterans often initially disclose their MST to a mental health provider (MHP), these providers operate in a unique circumstance where they may be the individual’s first point of contact for determining STI risk. In these circumstances, the MHP should consider the utility of briefly assessing the patient’s sexual health and making subsequent medical referrals as necessary.

To accurately assess a patient’s STI risk, the MHP should gather information regarding both current/acute risk (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact, for instance, genital contact without a condom or oral sex without a dental dam, in the past month?”) as well as longer standing (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact... in the past year?”) STI risk. Providers also should consider oral, anal, and genital modes of sexual contact as well as common STI symptoms (eg, warts, sores, genital discharge, and/or pain or burning sensation when peeing or during sex). Additionally, psychoeducation should be provided, especially information regarding the asymptomatic nature of certain STIs, such as HIV and HPV, and the risk of transmission in all forms of sexual contact, including nongenital anal contact. Appropriate referrals to sexual health education, including safe sex practices, also should be considered in order to minimize risk of future STI transmission.

Mental health providers also should determine the date of patient’s most recent STI test. Not all STIs can be detected via a blood test or routine yearly Papanicolaou (Pap test) physicals. Additionally, MHPs should be aware that risky practices, including substance misuse, are more common in survivors of MST and that there is an association between substance misuse and STIs.2,6 If testing has not occurred recently, MHPs should strongly encourage the individual to access STI testing and provide resources as necessary, such as access to low-cost STI testing. Further, if the MHP has reason to suspect the presence of an STI after the brief assessment (eg, individual endorses unprotected sexual contact or risky behaviors, including substance misuse, sex trading, and STI symptomatology; a positive STI test but the patient has not accessed treatment), an appropriate sexual health referral should be made.

During the assessment and psychoeducation processes, terminology and language plays an integral role. If a MHP assumes an individual has sexual contact only with opposite sex partners (eg, asking a male “How many women have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?” vs “How many partners have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?”), the MHP will not accurately assess the individual’s level of current risk. Additionally, it is important to remember that sexual behavior does not always align with sexual identity: A man who identifies as heterosexual may still have sexual contact with men. Due to the sensitive nature of sexual health, MHPs should be careful to use nonjudgmental language, such as using the term sex work rather than the more pejorative term prostitution, to avoid offending patients and to increase their likelihood to disclose sexual health information.

Nonjudgmental language is especially relevant when working with gender-minority veterans (eg, transgender, gender nonconforming, gender transitioning), because this clinical population has a higher risk of victimization and lower rates of help-seeking health behavior.7 In particular, a sizable portion of individuals who identify as transgender do not seek services out of fear that they will be discriminated against, humiliated, or misunderstood.7 To assuage these concerns, MHPs should ensure they refer to the veteran with the veteran’s preferred pronouns. For example, a MHP could ask “I would like to be respectful, how would you like to be addressed?” or “What name and pronoun would you like me/us to use?” Providers also should consider nonbinary pronouns when appropriate (eg, singular: ze/hir/hirs; plural: they/them/theirs). Providers also should recognize that making a mistake is not uncommon, and they should apologize to maintain rapport and maximize the patient’s comfort during this distressing process. Further, MHPs should consider additional training, education, and/or consultation if they feel uncomfortable or ill prepared when working with gender-minority veterans.