Veterans had a follow-up visit to review the test results. Patients were counseled on treatment recommendations, including a copy of current consensus recommendations, and disclosure to the family. The recommendations were then included in the patient’s electronic medical record. For example, BRCA patients had a discussion of risks and benefits of various management options, including breast magnetic resonance imaging, prophylactic mastectomy, and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, once childbearing was complete.

Results

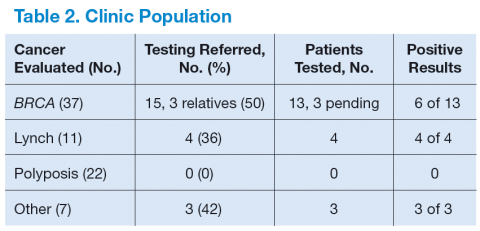

Table 2 shows the number of veterans referred to the GCRA clinic since it started in late 2010, categorized by the likely genetic syndrome, the number and percentage of veterans where genetic testing was recommended, and the results of testing. Four veterans, 2 with LS, 1 with CHEK2 mutation, and 1 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, were identified outside the VA system but were referred for counseling. One of the veterans with LS was referred by an outside provider who obtained a suspicious family history, and the other was identified via pathologic screening. The miscellaneous group included 1 veteran with MEN 1 and 1 veteran with Birt-Hogg-Dube.

There are a number of interesting results. Although the number of patients referred for LS was low, the number of annual referrals for possible BRCA was about equal to the number of patients with breast cancer who were diagnosed and treated yearly. Although this could have been due to pent up demand initially, the number of annual referrals has not decreased with time. Furthermore, the number of patients referred for polyposis has been considerably higher than would be expected by the rarity of attenuated FAP. Initially, patients with 10 to 20 polyps of any type were referred for evaluation. All but 1 had their first polyp diagnosed after the age of 50 years. Five veterans who were referred to GCRA had < 10 polyps lifetime, 3 veterans had between 10 and 20 polyps, and 12 veterans have had ≥ 20 adenomatous polyps over their lifetime. None seen to date have had a personal or family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer.

Discussion

A genetic cancer risk assessment clinic was set up in a VA hospital and has been running successfully for 4 years. Although many parts of setting up such a clinic are common to a community GCRA clinic, there are also aspects that are specific to a VA setting. 6

Because genetic testing is relatively expensive, a budget must be set up and approved by VA administration. This budget is based on the estimated number of veterans that will be referred yearly, the likely percentage that will need to be tested, and the cost of testing. Currently, the average cost of a single gene test is about $2,000 to $3,000. Some patients will need to have 2 to 4 genes tested. Furthermore, many centers are now moving to multigene testing, and the cost of these panels is about $10,000 or more, though this is less than the cumulative cost of the genes done individually.

Since there is currently no national VA contract for genetic cancer testing, each VA facility needs to negotiate contracts with outside laboratories. Several of these laboratories offer gene panel testing, but the panels vary from one laboratory to another.