Treatment

Unfortunately, no pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic therapy has been shown to reverse or halt the progression of OA. A comprehensive approach to the treatment of patients with OA is imperative for reducing disability and improving quality of life. Several sources have published guidelines for the management of OA. 9-11 More recently, comprehensive clinical practice guidelines have been published regarding nonsurgical management of hip and knee OA in the veteran population. 12

Initially, a conservative approach is generally recommended with reduction of modifiable risk factors and patient education. Weight loss, aerobic conditioning, and physical therapy can improve function and stability. Notably, a weight reduction of 5% has been associated with an 18% to 24% improvement in knee OA. 6 A supervised walking exercise program can be extremely beneficial for patients, with several studies showing improvement in pain, ambulatory function, and psychological well-being. Bracing devices and orthotic footwear can be helpful for compartmental unloading of the knee. The use of ambulatory assist devices (eg, canes, walkers) and splinting may also be of benefit. Topical lidocaine, capsaicin, and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) therapy can be useful adjuncts.

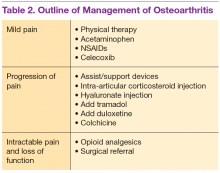

Medications are used mainly to provide analgesia and improve function while causing the fewest adverse effects (AEs) (Table 2). Contrary to conventional teaching, acetaminophen may not be as effective in the treatment of OA as previously thought. A recently published metaanalysis comparing treatments for knee OA revealed acetaminophen to be the least effective agent. 13 Another meta-analysis showed that acetaminophen provided clinically insignificant pain relief in OA of the hip and knee. 14 However, acetaminophen may be useful in the treatment of mild OA or in patients with contraindications to other oral therapies. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy is more effective in a patient with inflammatory OA symptoms (eg, effusion, erosive OA) and can be added to acetaminophen if ineffective alone. Gastrointestinal protection against ulceration may be warranted, and use of NSAIDs may be contraindicated in the patient with high bleeding risk, renal insufficiency, or cardiovascular disease. In patients with low cardiac risk, celecoxib can be effective. Patients who have a contraindication to NSAIDs may find benefit from other analgesic agents, such as tramadol or duloxetine. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections can be particularly helpful for patients with a single osteoarthritic joint that has been unresponsive to oral or topical analgesics. Opioid analgesics may be used as a last resort when all other agents and therapies have failed. Most patients who require opioid therapy are awaiting surgical repair or are not surgical candidates.

Use of nutritional supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of primary knee OA is controversial. These agents are not regulated by the FDA and their potency, purity, and safety are not guaranteed. Furthermore, the bioavailability of oral glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate is particularly poor, and studies have revealed conflicting evidence on their ability to reduce pain in patients with OA. Nonetheless, some evidence exists for cartilage proteoglycan integration and synthesis with glucosamine and chondroitin compounds. Most patients taking these supplements experience few AEs, and some report good responses to therapy. Some patients allergic to shellfish may experience a reaction to glucosamine products.