Discussion

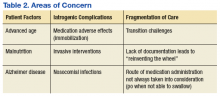

Following the IM injection of paliperidone palmitate, Mr. W had a complicated hospital stay resulting in his demise from sepsis and multiorgan failure. Severe immobilization, rigidity, and dystonia prevented Mr. W from conducting activities of daily living, which resulted in invasive interventions, such as continued foley catheterization. His sepsis was likely secondary to aspiration, catheterization, and eventual ventilation—all iatrogenic complications. Previous estimates in the U.S. have suggested a total of 225,000 deaths per year from iatrogenic causes.8

There are several areas of concern. Clearly, Mr. W had severe illness that greatly affected his life. He was estranged from family and had endured a 2-decade period of homelessness. He deserved effective treatment for his psychiatric illness to relieve his suffering. His long period of mental illness without effective treatment very likely biased the initial treatment team toward an aggressive approach.

Fragmented Care

The prolonged hospital stay and multiple complications directly led to fragmentation in Mr. W’s care. He was hospitalized for months on 3 different main services: psychiatry, medicine, and the MICU. Even when he remained on the same service, the primary members of his treatment team changed every few weeks. Many different specialties were consulted and reconsulted. Members of the specialty consult teams changed throughout the hospitalization as well. Given the nature of the local clinical administration, Mr. W likely received the most consistent team members from the attendings on the psychiatry consult-liaison service (who do not rotate) and from a local subspecialty delirium consult team (all members stay consistent except pharmacy residents).

Documentation of clinical reasoning behind treatment decisions was not ideal and occasionally lacking. This led to a tendency to “reinvent the wheel” with Mr. W’s treatment approach every few weeks. It was not until Mr. W had spent a significant amount of time on the medical service that an interdisciplinary treatment team meeting involving medicine, psychiatry, nursing, delirium, and neurology experts occurred. Although the interdisciplinary meeting helped by reviewing the hospital course, agreeing on a likely cause of the symptoms, and creating a treatment plan going forward, Mr. W was not able to recover.

Even when team members were stable, communication in a timely fashion did not always occur. At several points, expert recommendations were delayed by a day or more. Difficulties in treatment implementation were not communicated back to the specialty teams. The most significant example was a delay in recognition when Mr. W could no longer take oral pills secondary to the parkinsonism. Many days passed before an alternative liquid or dissolved medication was recommended on 2 separate occasions.

Subspecialty Consult

Addressing these documentation, communication, and transition challenges is neither easy nor unique to this large rural VA medical center. The authors have attempted to address this in the local system with the creation of a delirium team subspecialty consult service. Team members do not rotate and are able to follow patients throughout their hospital course. At the time of Mr. W’s hospitalization, the team included representatives from nursing, psychiatry, and occasionally pharmacy. Since then, it has expanded to include geriatrics and medicine. In addition to delirium being a marker for complex patients at risk for hospital complications, medical reasons for an extended length of stay could serve as a trigger for a referral to such a team of experts. In Mr. W’s case, that could have led to interdisciplinary consultation up to 2 months before it occurred. This may have led to a much better outcome.

Secondary parkinsonism is most notable with the typical antipychotics. The prevalence can vary between 50% and 75% and may be higher within the elderly population. However, all antipsychotics have a chance of demonstrating EPS. Risperidone has a low incidence at low doses; studies have shown dose-related parkinsonism at doses of 2 to 6 mg/d. Significant risk of parkinsonism is further exacerbated when drug-drug interactions are considered.9 Concurrently receiving 2 antipsychotics, olanzapine and paliperidone, initially caused the EPS. The veteran’s cerebral atrophy from significant malnutrition related to chronic homelessness, and the presence of Alzheimer disease only identified postmortem exacerbated this AE. Further complicating the management of the EPS, paliperidone palmitate has a long half-life of 25 to 49 days.9 Simply discontinuing the medication did not remove it from Mr. W’s system. Paliperidone would have continued to be present for months.

Conclusion

In this case, aggressive changes in the antipsychotic medications in a short period led to Mr. W effectively having 3 different agents in his system at the same time. This significantly elevated his risk of AEs, including parkinsonism. The clinician must be vigilant to further recognize the initial symptoms of parkinsonism on clinical presentation. Administration of clinical scales, such as the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effect, can help in these situations.10 Malnutrition and increased age can predispose patients to neurolepticAEs, so treatment teams should exercise caution when administering antipsychotics in such a population. Pharmacokinetic changes in all major organ systems from aging result in higher and more variable drug concentrations. This leads to an increased sensitivity to drugs and AEs.9

Given the increasing geriatric patient population in the U.S., treating mania in the elderly will become more common. Providers should carefully consider the risks vs benefit ratio for each individual because a serious adverse reaction may result in detrimental consequences. Even with severe symptoms leading to a bias toward an aggressive approach, it may be better to “start low and go slow.” Early inclusion of interdisciplinary expertise should be sought in complex cases.