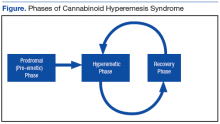

The prodromal, or preemetic phase, is characterized by early morning nausea without emesis and abdominal discomfort. The hyperemetic phase begins when the patient accesses the health care system via either the ED or primary care physician. This phase is characterized by intractable nausea and vomiting and may be associated with mild diffuse abdominal pain. The nausea and vomiting typically do not respond to antiemetic medications. Patients in this stage also develop a compulsive behavior of hot showers that temporarily relieve the symptoms. These behaviors are thought to be learned through their cyclical periods of emesis and may not be present during the first few hyperemetic phases. During the recovery phase, the patient returns to a baseline state of health and often ceases utilizing the hot shower. The recovery phase can last weeks to months despite continued cannabis use prior to returning to the hyperemetic phase (Figure).6,7

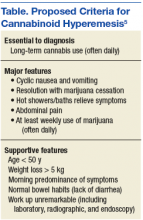

Simonetto and colleagues proposed clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CHS based on their case series as well as on previously proposed criteria presented by Sontineni and colleagues.5,8 Long-term cannabis use is required for the diagnosis. In the Simonetto and colleagues case series, the majority of patients developed symptoms within the first 5 years of cannabis use; however, Soriano and colleagues conducted a smaller case series that showed that the majority of subjects used marijuana for roughly 16 years prior to the onset of vomiting.5,7

The major CHS features that suggest the diagnosis are severe cyclic nausea and vomiting, relief of symptoms with abstinence from cannabis, temporary symptom relief with hot bathing, abdominal pain, and at least weekly use of marijuana. Other supportive features include aged < 50 years, weight loss > 5 kg, symptoms that are worse in the morning, normal bowel habits, and negative evaluation, including laboratory, radiography, and endoscopy (Table).5The differential diagnosis for nausea and vomiting is very broad, including several gastrointestinal,peritoneal, central nervous system, endocrine, psychiatric, and metabolic causes. The suggested initial workup includes laboratory evaluation with CBC with differential, complete metabolic panel, lipase, urine analysis, UDS, and abdominal series. Further imaging and EGD may be indicated in certain patient populations, depending on the patient presentation.6 When performed, the EGD can show a mild, nonspecific gastritis or distal esophagitis.7

Treatment often is supportive with emphasis placed on marijuana cessation. Intravenous fluids often are used due to dehydration from the emesis. The use of antiemetics, such as 5-HT3 (eg, ondansetron), D2 (eg, prochlorperazine), H1 (eg, promethazine), or neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (eg, aprepitant) can be tried, but these therapies often are ineffective. Diet can be advanced as the patient tolerates. Given that many patients are found to have a mild gastritis, H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors may be used. Extensive counseling on marijuana cessation is needed as it is the only therapy shown to have prolonged relief of the hyperemetic phase.6 The length of cessation from marijuana for resolution of the cyclical hyperemesis varies from 1 to 3 months. Returning to marijuana use often results in the returning of CHS.5

The pathophysiology of CHS is largely unknown; however, there are several hypothesized mechanisms. Many theorize that due to the lipophilicity and long half-life of THC, a primary compound in marijuana, it accumulates in the body over time.4,6 It is thought that this accumulation may cause toxicity in both the gastrointestinal tract as well as in the brain. Central effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis may play a major role, and the reason for the symptom relief of hot baths is due to a change in thermoregulation in the hypothalamus.5 One interesting mechanism relates to CB1 receptor activation and vasodilation within the gastrointestinal tract due to chronic THC accumulation. The relief of the abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with hot showers can be secondary to the vasodilation of the skin, causing a redistribution from the gut. This theorized mechanism has been referred to as “cutaneous steal.”9

Conclusion

With the increased prevalence of marijuana use in the U.S. over the past decade and reform in legislation taking place over the next couple of years, it is increasingly important to be able to recognize CHS to avoid frequent hospital utilization and repeated costly evaluations. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is recognized by the triad of chronic cannabis use, cyclical hyperemesis, and compulsive hot bathing.4

The syndrome has 3 phases. In the prodromal phase the patient has morning predominance of nausea, usually without emesis. This is followed by the hyperemesis phase, which is characterized by hyperemesis, vague abdominal pain, and learned compulsive hot bathing.

The third phase is the recovery phase, which is a return to normal behavior. During the recovery phase, if patients cease marijuana use, they remain asymptomatic; however, if patients continue to use marijuana, they often have recurrence of the hyperemesis phase.5 The diagnosis of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is difficult as it is a diagnosis of exclusion. Patients may present to the ED many times prior to diagnosis. With the changing climate of marijuana laws, it is an important condition to consider when establishing a differential. More studies will be required to evaluate the overall prevalence of this condition as well as if there are any changes following the liberalization of marijuana laws in many states.