Study Outcomes

There were 2 primary endpoints: difference in percentage of patients who achieved target ACEI or ARB doses and difference in percentage of patients who achieved target BB doses. Secondary endpoints were difference between PMTC and no-PMTC groups in percentage of patient achievement in clinical GDMT; percentage medication adherence; percentage of patients with change in NYHA class of HF; percentage of patients with change in EF, including mean change; percentage of patients with 30-day and 90-day readmissions for HF; mean LOS if readmitted within 30 days and 90 days; percentage of patients with ED visits for HF within 6 months after baseline; and percentage mortality within 6 months after baseline.

Statistical Analysis

A 2-tailed Fisher exact test was used for nominal data, and a Student t test for continuous data. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 228 HFDMP enrollees, 29 were seen in the PMTC during the study period, and 199 were not seen in the PMTC. Of the 29 patients seen in the PMTC, 24 met the criteria for the PMTC study group. Charts of 106 of the 199 patients not seen in the PMTC were randomly reviewed until 24 patients who met the study criteria were selected for the no-PMTC study group. Thus, the PMTC group and the no-PMTC group each had 24 patients for 1:1 comparison. Eighty-seven patients were excluded from the study: 22 with EF > 40%, 50 with 1 or no appointment attended, and 15 who were enrolled in HFDMP before April 15, 2011.

Mean age was 66 years. All patients were male, and most were African American. The baseline characteristics of the PMTC and no-PMTC groups were similar, except a higher percentage of patients in the PMTC group had NYHA class II or III of HF (Table 1).

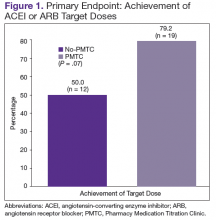

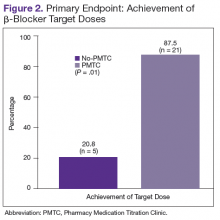

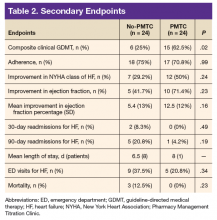

The ACEI or ARB target dose was achieved by a higher percentage of patients in the PMTC group, 79.2% (n = 19) vs 50% (n = 12), but the difference was not significant (P = .07) (Figure 1). However, BB target dose was achieved by a significantly higher (P = .01) percentage of patients in the PMTC group, 87.5% (n = 21) vs 20.8% (n = 5)(Figure 2). Furthermore, a significantly higher (P = .02) percentage of patients in the PMTC group, 62.5% (n = 15) vs 25% (n = 6), achieved composite clinical GDMT (Table 2). Last, there was not a statistically significant difference in 80% adherence with ACEI or ARB dosing or with BB dosing between the PMTC group (70.8%; n = 17) and the no-PMTC group (75%; n = 18).

For a higher percentage of patients in the PMTC group, 50% (n = 12) vs 29.2% (n = 7), NYHA class of HF improved, but the difference was not significant (P = .24). In addition, EF improved in a higher percentage of patients in the PMTC group, 71.4% (n = 10) vs 41.7% (n = 5), and mean (SD) improvement in EF was higher in the PMTC group, 12.5% (12%) vs 5.4% (13%), but neither difference was significant (P = .23 and P = .16, respectively).

A higher percentage of patients in the no-PMTC group were readmitted for HF within 30 days, 8.3% (n = 2) vs 0%, but the difference was not significant. Likewise, a higher percentage of patients in the no-PMTC group were readmitted for HF within 90 days, 20.8% (n = 5) vs 4.2% (n = 1; P = .19). Mean LOS for these readmissions was longer in the PMTC group, 8 days (n = 1) vs 6.5 days (n = 8). There was a higher percentage of ED visits for HF in the no-PMTC group, 37.5% (n = 9) vs 20.8% (n = 5), but did not reach statistical significance (P = .34). Last, the no-PMTC group had a higher percentage of deaths within 6 months after baseline, 37.5% (n = 9) vs 20.8% (n = 9), which also was not significant.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that, within HFDMPs, there is a role for a pharmacist who has prescribing authority and interacts face-to-face with patients in the clinic. Significantly more patients in the PMTC group achieved target BB doses by the end of the study. Target doses of BBs have been found to decrease morbidity and mortality.8-10

The present study also found a positive trend toward achieving target ACEI or ARB doses. Reasons for not achieving target doses included contraindication to the medication, medication discontinuation during hospital admission, hypotension, hyperkalemia, and titration not complete by end of study period. Two of the many reasons for titration not being complete were clinic enrollment timing and nonadherence. Although achievement of target ACEI or ARB doses did not reach statistical significance, statistically significantly more patients achieved composite clinical GDMT.

As defined in the study, clinical GDMT captured the prescribing of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate in patients intolerant to ACEIs and ARBs. This study, the first known to evaluate achievement in GDMT, demonstrated a pharmacist’s ability to titrate more than just ACEI, ARB, and BB doses. This finding is clinically important in that appropriate pharmacologic therapy can reduce the number of hospitalizations for HF and improve survival, even though the study found that its PMTC group showed only trends toward fewer 30-day and 90-day readmissions for HF, fewer ED visits for HF, and less mortality.6 This finding may be attributable to the small number of readmissions for HF and deaths among the study groups.

One endpoint that did not show an expected difference with pharmacist intervention was medication adherence. However, medication nonadherence likely was a reason for patient referral to the PMTC. Baseline medication adherence was not determined, so improvement in adherence could not be assessed. Findings might have been different, too, if medication adherence had been evaluated with patient interviews and refill history, not just refill history.

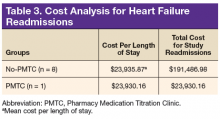

In the PMTC group, LOS for readmissions for HF did not improve. However, the group had only 1 readmission, which may have skewed the result. No studies have linked outpatient pharmacist intervention to decreased LOS for readmission for HF. The endpoint was evaluated to assess whether medication stability leads to reduced LOS and to complete a limited cost analysis. Analysis of mean cost based on number of readmissions, bed type, and LOS revealed a cost savings of $167,556.82 for the PMTC group (Table 3). Other potential cost savings that are difficult to quantify and that were not accounted for include extended time between ED visits or readmissions for HF and increased quality of life and daily functioning.

This is the first study known to evaluate a pharmacist who had prescribing authority and interacted face-to-face with patients. Other studies have evaluated the role of the pharmacist in the multidisciplinary management of patients with HF. In 1999, the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) study reported the effect of direct HF-related patient care by a pharmacist who performed medication evaluations, provided patient education, and made medication recommendations to a physician.11

After a medication dosing change, the pharmacist provided telephone follow-up to assess for problems with the drug therapy and then, if any were identified, referred patients to the physician. Pharmacist intervention demonstrated a decrease in all-cause mortality and HF events and an increase in ACEI doses. Unlike the pharmacist in the present study, the pharmacist had to get recommendations approved and prescribed by a physician. The present PMTC allows for pharmacist intervention, including medication therapy changes and follow-up appointments without consultation with a physician. If needed, the HF cardiologist is available in the HFDMP clinic or by telephone.

Jain and colleagues evaluated a protocol-driven medication titration clinic staffed by nurse and pharmacist specialists.12 Although their study was limited by its descriptive nature, the authors concluded that the clinic increased the number of patients who achieved target ACEI/ARB or target BB doses. In the present study, the percentage of PMTC patients who achieved target doses increased during the study period, from 50% to 79.2% (ACEI/ARB) and from 20.8% to 87.5% (BB). Unlike other clinic pharmacists, however, the PMTC pharmacist titrates medications independently and does not follow a set clinic protocol.

Similar to the PHARM study, the Heart Failure Optimal Outcomes From Pharmacy Study (HOOPS) evaluated pharmacists who worked collaboratively with physicians to optimize HF therapy.13 As in the PMTC, patients and pharmacists had 30-minute appointments together. In HOOPS, however, physician agreement was needed before pharmacist recommendations were implemented. That study found that more patients with pharmacist intervention started an ACEI or ARB, had the medication titrated, and received recommended doses. More patients also either started a BB or increased its dose, but this did not increase the number of patients who received recommended BB doses. In addition, pharmacist intervention did not affect clinical outcomes. The authors acknowledged this finding might be attributable to the pharmacists’ lack of proper HF management training. Patients in the study were also more stable, whereas PMTC patients arrived after HF discharge and were followed until medication therapy was optimized. The HOOPS followed patients for only 3 or 4 visits, regardless of target dose achievement status.

In a study conducted within the VA health care system, Martinez and colleagues evaluated the use of pharmacists who had prescribing authority and were permitted to order laboratory tests under a scope of practice similar to that in the present study.14 However, their coordination agreement allowed them only to initiate and adjust doses of certain HF medications according to defined protocols. The pharmacist conducted monthly education classes and had medication titration appointments with individual patients by telephone over 2-week intervals. Face-to-face appointments were limited to medication reconciliations, whereas all appointments in the present study were face-to-face. In addition, Martinez and colleagues found that a higher percentage of patients who attended pharmacist appointments achieved target ACEI, ARB, and BB doses, whereas the present study found a higher percentage only of achieved target BB doses, not ACEI or ARB. However, the present study also found increased composite clinical GDMT achievement, which Martinez and colleagues did not evaluate. As mentioned, GDMT achievement may be a broader evaluation of optimal HF medical therapy, as it incorporates ACEI or ARB intolerance.

Martinez and colleagues acknowledged several study limitations different from those of the present study.14 Most members of their study population were white men, unlike this study’s population. Combining these 2 studies’ results may support use of pharmacist intervention for both white and African American men. In addition, the authors noted that patients often forgot their medications or were confused about doses, and concluded that forgetfulness and confusion may stem from having only telephone interviews and lacking written instructions for the interval between clinic appointments. By contrast, all PMTC patients were seen face-to-face, and handouts detailing any changes helped minimized confusion. Even with face-to-face appointments, however, patient nonadherence persisted, making it difficult to optimize HF therapy. Patients did not always follow instructions to bring HF medications (or medication lists) and daily weight measurements to clinic visits, which complicated medication reconciliations, interventions, and educational efforts regarding dose changes. Furthermore, patients sometimes missed face-to-face appointments, often because of transportation difficulties. In these situations, telephone appointments may be beneficial. The obstacle of transportation is removed, and, during the at-home telephone call, the patient has easy access to medications and measurements.