Discussion

Several international study groups have recommended establishing standards for timely care of patients with known or suspected lung cancer. 5-10 According to a study in Brazil, an application interval exceeding 30 days is considered patient delay. 6 The Swedish Lung Cancer Study Group recommended that diagnostic tests be completed within 4 weeks in 80% of all patients and that treatment be started within 2 weeks thereafter. 7 The recommendations from Canada are a maximum of 4 weeks between first PCP visit and diagnosis and 2 weeks for surgery. 8 The British Thoracic Society recommended that all patients have completed diagnostic tests within 2 weeks of request with specific time intervals for treatment initiation based on treatment modality. 9

Numerous studies 10-27 and 2 meta-analyses 28,29 have addressed timeliness of care or associations between timeliness and clinical outcomes, and 1 study 27 tested an intervention to improve timeliness of care in patients with lung cancer. These studies varied in important ways because of the complexities inherent in the diagnosis and management of lung cancer, patient- and system-specific factors, and the definitions used for “delays.”

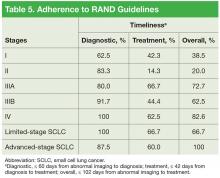

For this study, the authors examined Dayton VAMC adherence to RAND guidelines regarding time from imaging to diagnosis, time from diagnosis to treatment initiation, and time from abnormal imaging to treatment initiation. Separately, the authors examined the impact of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation on delay.

The 89.2% adherence to RAND diagnostic time guidelines (avoiding diagnostic delay) in this study’s population (excluding patients who participated in cardiopulmonary rehabilitation) was better than the 59% and 68.8% found in 2 larger VAMC studies. 24,26 In addition, adherence to the RAND time standard for the interval from diagnosis to treatment initiation (avoiding treatment delay) was similar between this study (58.6%) and one of those studies (62.2%), which was a multicenter investigation. 26 The other VAMC study, a singleinstitution investigation, was superior to the present study with respect to avoiding treatment delay (adherence, 76% vs 58.6%). 24 These overtly similar results suggest that system delay is accompanied by patient delay involving time for decision making, acute illness, missed appointments, and so forth.

In this study, timeliness was most disappointing for the patients who underwent primary surgical resection. Surgery patients’ poor diagnostic timeliness rate (14.3%) was likely multifactorial, involving additional pretissue procurement staging workup, including more imaging scans, invasive procedures (mediastinoscopy), and repeat biopsy in cases of negative initial biopsy results. In addition, patients who initially qualified for definitive surgical resection of early-stage lung cancer likely underwent extensive postdiagnostic workup that included pulmonary function testing, split-function studies, and preoperative assessment for cardiac clearance. In a single-center prospective study, O’Rourke and Edwards found that progression of early-stage lung cancer after a median system delay of 94 days resulted in decreased candidacy for curative therapy in 21% of patients. 22

Surgical resection was previously thought to be the best curative option for early-stage lung cancer. However, recent data on use of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) in early-stage non-SCLC (NSCLC) showed equivalent outcomes. In a pooled study, Chang and colleagues found 3-year overall survival of 95% in their SABR group and 79% in their surgery group. 30 Given these data, findings from this study, and significant delays experienced by surgery patients, it is worth considering whether SABR should be used more often.