Results

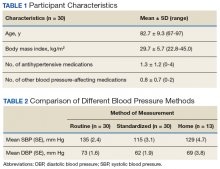

Thirty veterans aged > 65 years participated in the study. The average age (SD) was 82.7 (9.3) years. The average BMI (SD) was overweight at 29.7 kg/m2 (5.7). Most (87.6%) of the study participants had been diagnosed with hypertension prior to the study, and no new diagnoses were made as a result of the study.

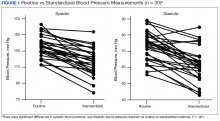

Participants were prescribed an average of 1.3 antihypertensive medications and 0.8 medications that had BP effects (Table 1).Both systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BPs (DBP) measured by the standardized method were significantly lower than those by the routine method (P < .01 and P < .01, respectively) (Figure 1).

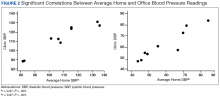

The average SBP measured by routine method was 135 mm Hg compared with 115 mm Hg for the standardized method (Table 2). The average routine method DBP was 73 mm Hg vs 62 mm Hg by the standardized method (Table 2). Home BPs approximated routine BPs more closely with an average SBP of 129 mm Hg and DBP of 69 mm Hg. All participants were given instructions about how to monitor BP, but only 13 out of 30 returned completed home BP logs. There was no statistically significant difference between home and routine or between home and standardized BP readings.To determine the accuracy of the home BP monitors, the average routine VAGLAHS BP measure was compared with home BP results. For SBPs, there was a significant correlation coefficient of 0.91 (P < .01).

For DBPs, the correlation coefficient was 0.97 and were also significant (P < .01) (Figure 2).Discussion

The present study demonstrated that standardized measurements of BP were lower than that of the routine method used in most office settings. These results suggest that there could be a risk of overtreatment for some patients those of whose results are higher than the SPRINT BP target of < 120/80 mm Hg. Clinicians might be treating BPs that are elevated due to improper measurement, which can lead to deleterious consequences in older adults, such as syncope and falls.16

Each participant exhibited a significantly lower BP reading with the standardized method than the routine method. The 20-point decrease in SBP and 10-point decrease in DBP are clinically significant. The routine method of measurement was intended to simulate BP measurement in outpatient settings. There is usually little time structured for rest, and because the protocol established by the AHA and other professional organizations is time consuming, it usually is not strictly followed. With guidelines proposed by JNC 8 and new findings from SPRINT, the method of BP readings should be reviewed in all clinical settings.

While changes in BP management are not necessarily immediate, the differences in recommendations proposed by SPRINT and JNC 8 can lead to confusion regarding how intensely to treat BP. These recommendations guide clinical practice, but clinicians’ best judgment ultimately determines BP management. Physicians who utilize routine office measurements likely rely on BP readings that are higher on average than are readings done under proper conditions. This leads to the prospect of overtreatment, where physicians attempt to control hypertension too aggressively, potentially leading to orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and increased risk for falls.16 With findings from SPRINT recommending even lower BPs than that by JNC 8, overtreatment risk becomes especially relevant. While BP protocol was strictly followed in SPRINT, some clinicians may not necessarily follow the same fastidious protocol.

The average differences between the home and standardized BPs were not statistically significant possibly due to the small sample size in the home BP measurements; however, the difference might represent some clinical relevance. There was a 15-point difference in SBP results between home (129 mm Hg) and standardized (115 mm Hg) measures. There also was a difference in DBP between home (69 mm Hg) and standardized (62 mm Hg) results. The close correlation between both home and BPs measured in VAGLAHS demonstrated that any difference was not due to variability in the measurement devices. Previous studies have demonstrated that home BPs are better indicators of cardiovascular risk than office BP.8

Despite lack of statistical significance, home BPs were lower than routine, which suggests that they still may be more reliable than routine office measurements. Definitive conclusions regarding the accuracy of the home BPs in the present study cannot be drawn due to the small sample size (n = 13). Further exploration with comparisons to ambulatory BP monitoring could yield more information on accuracy of home BP monitoring.

In this study’s cohort of older veterans, the average BMI was between 25 and 30 (overweight), which is a risk factor for hypertension.17 Every participant with hypertension was taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication and being actively managed. In this study, the authors accounted for other medications that may affect BP, such as α blockers used in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.18 These could have potential elevating or lowering effects on BP measurements.

An issue in this study was the lack of adherence to home BP monitoring. Many patients forgot to bring in their records or to measure their BPs at home. The difficulties highlight real-life issues. Clinicians often request that patients monitor their BP at home, but few may actually remember, let alone keep diligent records. There are many barriers between measuring and reporting home BPs, which may prevent the usefulness of monitoring BP at home.