Physical exercise offers preventative and therapeutic benefits for a range of chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer disease, and depression.1,2 Exercise has been well studied for its antidepressant effects, its ability to reduce risk of aging-related dementia, and favorable effects on a range of cognitive functions.2 Lesser evidence exists regarding the impact of exercise on other mental health concerns. Therefore, an accurate understanding of whether physical exercise may ameliorate other conditions is important.

A small meta-analysis by Rosenbaum and colleagues found that exercise interventions were superior to control conditions for symptom reduction in study participants with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 This meta-analysis included 4 randomized clinical trials representing 200 cases. The trial included a variety of physical activities (eg, yoga, aerobic, and strength-building exercises) and control conditions, and participants recruited from online, community, inpatient, and outpatient settings. The standardized mean difference (SMD) produced by the analysis indicated a small-to-medium effect (Hedges g, -0.35), with the authors reporting no evidence of publication bias, although an assessment of potential bias associated with individual trial design characteristics was not conducted. Of note, a meta-analysis by Watts and colleagues found that effect sizes for PTSD treatments tend to be smaller in veteran populations.4 Therefore, how much the mean effect size estimate in the study is applicable to veterans with PTSD is unknown.3

Veterans represent a unique subpopulation in which PTSD is common, although no meta-analysis yet published has synthesized the effects of exercise interventions from trials of veterans with PTSD.5 A recent systematic review by Whitworth and Ciccolo concluded that exercise may be associated with reduced risk of PTSD, a briefer course of PTSD symptoms, and/or reduced sleep- and depression-related difficulties.6 However, that review primarily included observational, cross-sectional, and qualitative works. No trials included in our meta-analysis were included in that review.6

Evidence-based psychotherapies like cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure have been shown to be effective for treating PTSD in veterans; however, these modalities are accompanied by high rates of dropout (eg, 40-60%), thereby limiting their clinical utility.7 The use of complementary and alternative approaches for treatment in the United States has increased in recent years, and exercise represents an important complementary treatment option.8 In a study by Baldwin and colleagues, nearly 50% of veterans reported using complementary or alternative approaches, and veterans with PTSD were among those likely to use such approaches.9 However, current studies of the effects of exercise interventions on PTSD symptom reduction are mostly small and varied, making determinations difficult regarding the potential utility of exercise for treating this condition in veterans.

Literature Search

No previous research has synthesized the literature on the effects of exercise on PTSD in the veteran population. The current meta-analysis aims to provide a synthesis of systematically selected studies on this topic to determine whether exercise-based interventions are effective at reducing veterans’ symptoms of PTSD. Our hypothesis was that, when used as a primary or adjuvant intervention for PTSD, physical exercise would be associated with a reduction of PTSD symptom scale scores. We planned a priori to produce separate estimates for single-arm and multi-arm trials. We also wanted to conduct a careful risk of bias assessment—or evaluation of study features that may have systematically influenced results—for included trials, not only to provide context for interpretation of results, but also to inform suggestions for research to advance this field of inquiry.10

Methods

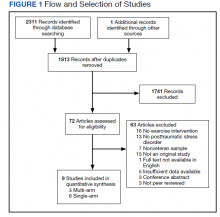

This study was preregistered on PROSPERO and followed PRISMA guidelines for meta-analyses and systematic reviews.11 Supplementary materials, such as the PRISMA checklist, study data, and funnel plots, are available online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1). Conference abstracts were omitted due to a lack of necessary information. We decided early in the planning process to include both randomized and single-arm trials, expecting the number of completed studies in the area of exercise for PTSD symptom reduction in veterans, and particularly randomized trials of such, would be relatively small.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study was a single- or multi-arm interventional trial; (2) participants were veterans; (3) participants had a current diagnosis of PTSD or exhibited subthreshold PTSD symptoms, as established by authors of the individual studies and supported by a structured clinical interview, semistructured interview, or elevated scores on PTSD symptom self-report measures; (4) the study included an intervention in which exercise (physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive in the sense that improvement or maintenance of physical fitness or health is an objective) was the primary component; (5) PTSD symptom severity was by a clinician-rated or self-report measure; and (6) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal.12 Studies were excluded if means, standard deviations, and sample sizes were not available or the full text of the study was not available in English.

The systematic review was conducted using PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases, from the earliest record to February 2021. The following search phrase was used, without additional limits, to acquire a list of potential studies: (“PTSD” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “posttraumatic stress disorder” or “post traumatic stress disorder”) and (“veteran” or “veterans”) and (“exercise” or “aerobic” or “activity” or “physical activity”). The references of identified publications also were searched for additional studies. Then, study titles and abstracts were evaluated and finally, full texts were evaluated to determine study inclusion. All screening, study selection, and risk of bias and data extraction activities were performed by 2 independent reviewers (DR and MJ) with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus (Figure 1). A list of studies excluded during full-text review and rationales can be viewed online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1).