Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

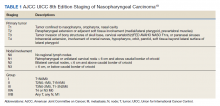

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

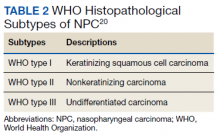

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.