Pancytopenia is a condition in which all 3 hematologic cell lines are lower than expected in the blood, often representing either an increase in cellular destruction or decrease in bone marrow production. Destruction often occurs in the setting of autoimmune conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis) or splenic sequestration, often affecting erythrocytes and platelets more than leukocytes. Decreased production represents central etiologies, which are often due to nutritional deficiencies, infections, drug toxicities, or malabsorption.1 Pancytopenia secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency is rare, accounting for about 5% of the hematologic manifestations of symptomatic vitamin B12 deficient patients.2

Pernicious anemia, named for a once lethal disease, is a form of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency that results from an autoimmune (type II hypersensitivity) reaction to gastric parietal cells or intrinsic factor. Antibodies bind to gastric parietal cells and reduce gastric acid production, leading to atrophic gastritis, or they bind intrinsic factor and block the binding and absorption of vitamin B12 in the gastrointestinal tract. While first described in the 1820s, it was not until a century later when scientists were studying hematopoiesis in response to the heavy casualty burden from battlefield exsanguination in World War I that dogs fed raw liver were noted to have significantly better blood regeneration response than those fed cooked liver. This discovery led physicians Minot and Murphy to use raw liver to treat pernicious anemia and found that jaundice improved, reticulocyte counts increased, and hemoglobin (Hb) concentration improved, resulting in the duo becoming the first American recipients of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.3 It was ultimately determined in 1948 by chemists Folkers and Todd that the active ingredient in raw liver responsible for this phenomenon was vitamin B12.4

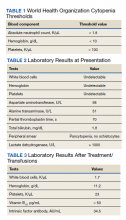

Patients with pernicious anemia typically present with macrocytic anemia, low reticulocyte count, hypersegmented neutrophils, as well as mild leukopenia and/or thrombocytopenia, distinguishable from folate deficiency by an elevated serum methylmalonic acid level. World Health Organization cytopenia thresholds are listed in Table 1.5 Treatment consists of lifelong vitamin B12 supplementation, and endoscopic screening is often recommended after diagnosis due to increased risk of gastrointestinal malignancy.6 Pernicious anemia can be difficult to distinguish from thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP), a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia that can cause rapid end-organ failure and death if treatment is delayed.7 While pernicious anemia is not typically hemolytic, case reports of hemolysis in severe deficiency have been reported.7 Adequate bone marrow response to hemolysis in TTP results in an elevated reticulocyte count, which can be useful in differentiating from pernicious anemia where there is typically an inadequate bone marrow response and low reticulocyte count.8,9

The approach to working up pancytopenia begins with a detailed history inquiring about medications, exposures (benzenes, pesticides), alcohol use, and infection history. A thorough physical examination may help point the health care practitioner (HCP) toward a certain etiology, as the differential for pancytopenia is broad. In the deployed soldier downrange, resources are often limited, and the history/physical are crucial in preventing an expensive and unnecessary workup.