Insulin injection therapy is one of the most widely used health care interventions to manage both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM/T2DM). Globally, more than 150 to 200 million people inject insulin into their upper posterior arms, buttocks, anterior and lateral thighs, or abdomen.1,2 In an ideal world, every patient would be using the correct site and rotating their insulin injection sites in accordance with health care professional (HCP) recommendations—systematic injections in one general body location, at least 1 cm away from the previous injection.2 Unfortunately, same-site insulin injection (repeatedly in the same region within 1 cm of previous injections) is a common mistake made by patients with DM—in one study, 63% of participants either did not rotate sites correctly or failed to do so at all.

Insulin-resistant cutaneous complications may occur as a result of same-site insulin injections. The most common is lipohypertrophy, reported in some studies in nearly 50% of patients with DM on insulin therapy.4 Other common cutaneous complications include lipoatrophy and amyloidosis. Injection-site acanthosis nigricans, although uncommon, has been reported in 18 cases in the literature.

Most articles suggest that same-site insulin injections decrease local insulin sensitivity and result in tissue hypertrophy because of the anabolic properties of insulin and increase in insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor.5-20 The hyperkeratotic growth and varying insulin absorption rates associated with these cutaneous complications increase chances of either hyper- or hypoglycemic episodes in patients.10,11,13 It is the responsibility of the DM care professional to provide proper insulin-injection technique education and perform routine inspection of injection sites to reduce cutaneous complications of insulin therapy. The purpose of this article is to (1) describe a case of acanthosis nigricans resulting from insulin injection at the same site; (2) review case reports in the literature describing injection-site acanthosis nigricans resulting from same-site insulin injections; (3) describe localized cutaneous complications associated with the use of insulin; and (4) discuss clinical implications and lessons learned from the literature.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old patient with an 8-year history of T2DM, as well as stable coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stage 3 chronic kidney disease, presented with 2 discrete abdominal hyperpigmented plaques. At the time of the initial clinic visit, the patient was taking metformin 1000 mg twice daily and insulin glargine 40 units once daily. When insulin was initiated 7 years prior, the patient received neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin for the first year and transitioned to insulin glargine. After 4 years of insulin therapy, insulin aspart was added and discontinued after 2 years. The patient’s hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 6.8%, suggesting good glycemic control.

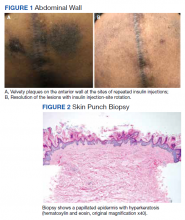

The patient reported 5 years of progressive, asymptomatic hyperpigmentation of the skin surrounding his insulin glargine injection sites and injecting in these same sites daily without rotation. He reported no additional skin changes or symptoms. He had noticed no skin changes while using NPH insulin during his first year of insulin therapy. On examination, the abdominal wall skin demonstrated 2 well-demarcated, nearly black, soft, velvety plaques, measuring 9 × 8 cm on the left side and 4 × 3.5 cm on the right, suggesting acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1A). The remainder of the skin examination, including the flexures, was normal. Of note, the patient received biweekly intramuscular testosterone injections in the gluteal region for secondary hypogonadism with no adverse dermatologic effects. A skin punch biopsy was performed and revealed epidermal papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis, confirming the clinical diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans (Figure 2).

After a review of insulin-injection technique at his clinic visit, the patient started rotating insulin injection sites over his entire abdomen, and the acanthosis nigricans partially improved. A few months later, the patient stopped rotating the insulin injection site, and the acanthosis nigricans worsened again. Because of worsening glycemic control, the patient was then started on insulin aspart. He did not develop any skin changes at the insulin aspart injection site, although he was not rotating its site of injection.

Subsequently, with reeducation and proper injection-site rotation, the patient had resolution of his acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1b).