Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare, usually self-limited cause of cervical lymphadenitis that is more prevalent among patients of Asian descent.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown. Clinically, KFD may mimic malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. The most common presentation of KFD involves fever and rapidly evolving cervical lymphadenopathy.2,3 Due to its rarity, KFD is not always considered in the differential diagnosis for fever with tender lymphadenopathy, and up to one-third of cases are initially misdiagnosed.2

Definitive diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. It is critical to achieving a timely diagnosis of KFD to exclude more serious conditions, initiate appropriate treatment, and minimize undue stress for patients. We describe a case of KFD in a patient who was met with delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis for his symptoms.

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old previously healthy White man presented to the emergency department with subacute, progressive right-sided neck pain and swelling. In the week leading up to presentation, he also noted intermittent fevers, night sweats, and abdominal pain. His symptoms were unrelieved with acetaminophen and aspirin. He reported no sick contacts, recent travel, or animal exposures. He had no known history of autoimmune disease, malignancy, or immunocompromising conditions. Vital signs at the time of presentation were notable for a temperature of 39.0 °C. On examination, he had several firm, mobile, and exquisitely tender lymph nodes in the right upper anterior cervical chain. Abdominal examination was notable for left upper quadrant tenderness with palpable splenomegaly. Due to initial concern that his symptoms represented bacterial lymphadenitis, he was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and admitted to the hospital for an expedited infectious workup.

Initial laboratory studies were notable for a white blood cell count of 3.7 × 109/L with 57.5% neutrophils and 27.0% lymphocytes on differential.

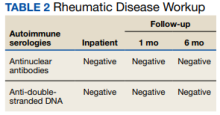

His hemoglobin level was 12.3 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 85.1 fL. A broad infectious workup including blood cultures and serologies was sent to evaluate for an infectious cause of lymphadenopathy. His serologies demonstrated evidence of prior infection with Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1, and HSV 2, but otherwise did not explain his current symptoms. Autoimmune serologic tests including antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) were unremarkable (Tables 1 and 2).