The costs for wound care play a significant role in total health care costs and are expected to rise dramatically. A 2018 Medicare analysis estimated chronic wound care cost $28.1 to $96.8 billion in supplies, hospitalization, and nursing care: Most costs were accrued in outpatient wound care.1 The global market for advanced wound care supplies is projected to reach $13.7 billion by 2027, and negative wound pressure therapy alone is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 5% over the analysis period 2020 to 2027.2 Chronic wound care also impacts the patient physiologically, socially, and psychologically. One study compared the 5-year mortality of a patient with a diabetic foot ulcer (30.5%) as similar to those patients with cancer (31%).3 Yet the investment in cancer research far outstrips wound care research.

There is no perfect wound dressing for all chronic wounds, but there is expert consensus on interventions that facilitate wound healing. In 2021, Nuutila and Eriksson stated that wound dressings should fulfill the following criteria: protection against trauma, esthetically acceptable, painless to remove, easy to apply, protection for the wound from contamination and further trauma, a moist environment, and an optimal water vapor transmission rate.4 Balanced moisture control is considered essential for healing chronic wounds. Indeed, moisture control within the wound bed may be the most important factor in chronic wound management and healing. The body communicates through a liquid medium, and if that medium is compromised, communication and marshaling of the immune and healing responses may become inefficient.4 Too much moisture, exudate, or fluid in the wound, and the healing is slowed; too little moisture in the wound results in a compromised responses from the body’s immune system, thus delaying healing. In 1988, Dyson and colleagues demonstrated that moist wound care was superior for the inflammatory and proliferative phases of dermal repair compared with dry wound care. The results showed that 5 days after injury, 66% of the cells in the moist wound were fibroblasts and endothelial cells vs 48% of those in the dry wounds.5

The question of dry vs moist wound care has resulted in various wound dressings that produce favorable moisture balance. Moisture balance in a wound creates the ideal environment for wound healing. Sound wound care practices promote the following physiologic responses: increased probability of autolytic debridement; increased collagen synthesis; keratinocyte migration and reepithelization; decreased pain, inflammation, scarring, and necrosis;enhancement of cell-to-cell signaling; and increase in growth factors.5,6 All these processes are mediated through proper wound moisture control. In addition to proper moisture control, antibiotics added to the wound care milieu (either directly to the wound or systemically) may have a place in chronic wound care. In 2013, Junker and colleagues reported that low-dose antibiotics combined with appropriate moisture balance in wounds demonstrated less scar tissue compared with dry wound care.6

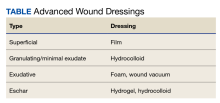

Approaches to chronic wound care are worlds apart: In developing nations the care of chronic wounds often involves traditional management with local products (eg, honey, boiled potato peels, aloe vera gel, banana leaves), whereas in developed nations, more expensive and technologically advanced products are available (eg, wound vacuum, saline wound chamber, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, antibacterial foam). Developing countries often do not have access to technologically advanced wound care products. Local products are often used by local healers, priests, and shamans. The use of these wound interventions in developing countries has produced satisfactory results. In contrast, developed countries have multiple chronic wound care products available (Table).

This report serves as an overview of the spectrum of products and strategies available to the wound care practitioner as well as a case presentation of a chronic wound in an otherwise healthy active-duty man in the Utah National Guard who required surgical debridement due to septicemia.