METHODS

We created a brief questionnaire regarding MMFC use and perspectives and distributed it to veteran patients at the infusion center at the CTHVAMC. The study was approved by the CTHVAMC department of research, and the institutional review board determined that informed consent was not required. The questionnaire did not collect any specific personal identifying data but included the participant’s sex, age, and diagnosis. Although there are standardized questionnaires concerning the use of CAM, we designed a new survey for MMFCs. The participants in the study were consecutive patients referred to the CTHVAMC infusion center for IV or other nonoral therapies. Referrals came from endocrinology, gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, neurology, rheumatology, and other specialties (eg, allergy/immunology).

The questionnaire was 1 page (front and back) and was completed anonymously without involvement by the study investigators or infusion center staff. Dated and consecutively numbered questionnaires were given to patients receiving therapy regardless of their diagnosis. Ages were categorized into groups: 18 to 30 years; 31 to 50 years; 51 to 65 years; and ≥ 66 years. Diagnoses were categorized by specialty: endocrinology, gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, neurology, rheumatology, and other. We noted in a previous similar study that the exact diagnosis was often left blank, but the specialty was more often completed.9 Since some patients required multiple visits to the infusion center, respondents were asked whether they had previously answered the questionnaire; there were no duplications.

The population we studied was under stress while receiving therapy for underlying illnesses. To improve the response rate and accuracy of the responses, we limited the number of survey questions. Since many of the respondents in the infusion center for therapy received medications that could alter their ability to respond, all questionnaires were administered prior to therapeutic intervention. In addition to the background data, respondents were asked: Do you apply magnets to your body, use magnetic field therapy, or copper devices? If you use any of these therapies, is it for pain, your diagnosis, or other? Would you consider participating in a clinical trial using magnets applied to the body or magnetic therapy?

RESULTS

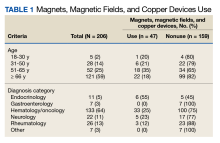

We collected 210 surveys. Four surveys were missing data and were excluded. The majority of respondents (n = 133, 64%) were in the hematology/oncology diagnostic group and 121 (59%) were aged ≥ 66 years (Table 1).

Most respondents (n = 173, 84%) were male.Respondents were asked whether they were using MMFC therapies. The results from all age groups showed an 18% overall use and in the diagnosis groups an overall use of 23%. Eighteen respondents (35%) aged 51 to 65 years reported using MMFC, followed by 6 respondents (21%) aged 31 to 50 years. Patients with an endocrinology diagnosis had the highest rate of MMFC use (6 of 11 patients; 55%) but more patients (33 of 133 [25%]) with a hematology/oncology diagnosis used MMFCs.

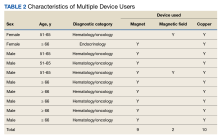

Copper was the most widely used MMFC therapy among individuals who used a single MMFC therapy. Twenty respondents reported copper use, 6 used magnets, and no respondents used magnetic field therapy (Table 2).

Some respondents reported the use of multiple therapies, including 2 who used magnetic field therapy (eAppendix, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0397).Although we were interested in understanding veterans’ use of these therapies, we were also interested in whether the respondent group would see MMFC as a potential therapy. The highest level of interest in participation in magnet clinical trials was reported by patients aged 31 to 50 years (64%) age group, followed by those aged 51 to 65 (62%). All of the respondents in hematology/oncology, rheumatology, neurology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology groups indicated that they would consider participating in clinical studies using magnets.