Although 2.4 million adults in the United States have been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, particularly among difficult to reach populations, such as persons who inject drugs, marginally housed individuals, correctional populations, and pregnant women.1 Though the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) broadened HCV screening recommendations to include individuals aged 18 to 79 years, rates of new HCV prescriptions sharply declined during the COVID-19 pandemic.2,3

During the pandemic, many health care systems adopted virtual health care modalities. Within the Veteran Health Administration (VHA), there was an 11-fold increase in virtual encounters. However, veterans aged > 45 years, homeless, and had other insurance were less likely to utilize virtual care.4,5 As health care delivery continues to evolve, health systems must adapt and test innovative models for the treatment of HCV.

There is limited understanding of HCV treatments when exclusively conducted virtually. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of the HCV treatment program at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, when telehealth modalities and mail-order prescriptions were used for HCV diagnosis and treatment. The secondary aim of this study was to understand patient factors associated with treatment initiation and discontinuation for patients using telehealth.

Methods

The VHA is the largest provider of HCV care in the US.6 At VAGLAHS, veterans with HCV are referred for evaluation to a viral hepatitis clinic staffed by gastroenterologists and infectious disease specialists. Veterans with detectable HCV on an HCV RNA test have an additional workup ordered if necessary and are referred to an HCV-specialist pharmacist or physician’s assistant to start treatment. In March 2020, all HCV evaluations and treatment initiation in the viral hepatitis clinic started being conducted exclusively via telehealth. This was the primary modality of HCV evaluations and treatment initiation until COVID-19 restrictions were lifted to permit in-person evaluations. Prescriptions were delivered by mail to patients following treatment initiation appointments.

We retrospectively reviewed electronic health records of veterans referred to start treatment March 1, 2020, through September 30, 2020. The endpoint of the reviewed records was set because during this specific time frame, VAGLAHS used an exclusively telehealth-based model for HCV evaluation and treatment. Patients were followed until June 15, 2021. Due to evolving COVID-19 restrictions at the time, and despite requests received, treatment initiations by the pharmacy team were suspended in March 2020 but HCV treatments resumed in May. Data collected included baseline demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, housing status, distance to VAGLAHS), comorbidities (cirrhosis, hepatitis B virus coinfection, HIV coinfection), psychiatric conditions (mood or psychotic disorder, alcohol use disorder [AUD], opioid use disorder), and treatment characteristics (HCV genotype, HCV treatment regimen, baseline viral load). Distance from the patient’s home to VAGLAHS was calculated using CDXZipStream software. Comorbidities and psychiatric conditions were identified by the presence of the appropriate diagnosis via International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes in the health record and confirmed by review of clinician notes. Active AUD was defined as: (1) the presence of AUD diagnosis code; (2) AUD Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) score of high or severe risk based on established cutoffs; and (3) active alcohol use noted in the electronic health record. All patients had an AUDIT-C score completed within 1 year of initiating treatment. Opioid use disorder was defined by the presence of diagnostic codes for opioid dependence or opioid abuse.

The reasons for treatment noninitiation and discontinuation were each captured. We calculated descriptive statistics to analyze the frequency distributions of all variables. Independent t tests were used to analyze continuous data and Pearson χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data. Statistical significance was set as P < .05.

Results

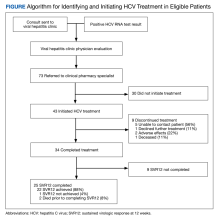

From March 1, 2020, through September 30, 2020, 73 veterans were referred to the HCV clinical pharmacist for treatment (Figure). Forty-three veterans (59%) initiated HCV treatment and 34 (79%) completed the full treatment course (Table 1). Twenty-five patients (65%) had their sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR12) testing and 22 patients achieved SVR12 (88%; 30% of total sample). One patient did not achieve SVR, and 2 patients died (variceal hemorrhage and progression of cerebral amyloidosis/function decline) before the completion of laboratory testing. From March 2020 to May 2020, HCV treatments requests were paused as new COVID-19 policies were being introduced; 33 patients were referred during this time and 21 initiated treatment.

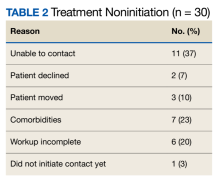

Veterans that did not start HCV treatment had a significantly higher rate of active AUD when compared with those that initiated treatment: 30% vs 9% (P = .02). Of the patients who started and discontinued treatment, none had active AUD. Other baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment characteristics were similar between the groups. No patient demographic characteristics were significantly associated with HCV treatment discontinuation. We did not observe any major health disparities in initiation or discontinuation by sex, race, ethnicity, or geography. Eleven patients (37%) could not be contacted, which was the most common reason veterans did not initiate treatment (Table 2). Of the 9 patients that did not complete SVR12, 5 patients could not be contacted for follow-up, which was the most common reason veterans discontinued treatment.