Mortality

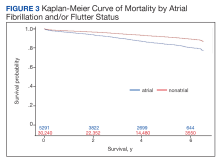

Over the 6-year study period, there was a lower survival probability for patients with AF/AFL. In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 129,391 total person-years, there were 3130 (8.8%) deaths and an incidence rate of 2.42 per 100 person-years. Death occurred 786 times with a 4.09 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL vs 2344 deaths and a 2.13 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). In the non-AF/AFL subgroup, death occurred 2344 times during a mean (SD) follow-up of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 110,151 total person-years. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of mortality by AF/AFL status.

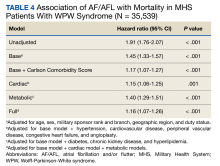

After adjusting for the base, metabolic and cardiac covariates, the HRs for mortality were 1.45 (95% CI, 1.33-1.57, P < .001), 1.40 (95% CI, 1.29-1.51, P < .001) and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.06-1.25, P = .001), respectively (Table 4). The HR after adjusting for the full model was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26, P < .001).

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, patients with WPW syndrome and comorbid AF/AFL had a significantly higher association with the cardiac composite outcome and death during a 3-year follow-up period when compared with patients without AF/AFL. After adjusting for confounding variables, the AF/AFL subgroup maintained a 12% and 16% higher association with the composite outcome and mortality, respectively. There was minimal difference in confounding effects between demographic data and metabolic profiles, suggesting one may serve as a proxy for the other.

To our knowledge, this is the largest WPW syndrome cohort study evaluating cardiac outcomes and mortality to date. Although previous research has shown the relatively low and mostly anecdotal SCD incidence within this population, our results demonstrate a higher association of adverse cardiac outcomes and death in an AF/AFL subgroup.16-18 Notably, in this study the AF/AFL cohort was older and had higher CCI scores than their counterparts (P < .001), thus inferring an inherently greater degree of morbidity and 10-year mortality risk. Our study is also unique in that the mean patient age was significantly older than previously reported (63 vs 27 years), which may suggest a longer living history of both ventricular pre-excitation and the comorbidities outlined in Figure 1.19 Given these age discrepancies, it is possible that our overall study population was still relatively low risk and that not all reported deaths were necessarily related to WPW syndrome. Despite these assumptions, when comparing the WPW syndrome subgroups, we still found the AF/AFL cohort maintained a statistically significant higher association with the 2 study outcomes, even after adjusting for the greater presence of comorbidities. This suggests that the presence of AF/AFL may still portend a worse prognosis in patients with WPW syndrome.

Although the association of AF and development of VF in patients with WPW syndrome—due to rapid conduction over the accessory pathway(s)—was first reported > 40 years ago, there has still been few large, long-term data studies exploring mortality in this cohort.19-25 Furthermore, even though the current literature attributes the development of AF with the electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, as well as intrinsic atrial architecture and muscle vulnerability, there is still equivocal consensus regarding EPT screening and ablation indications for asymptomatic patients with WPW syndrome.26-28 Notably, Pappone and colleagues demonstrated the potential benefit of liberal ablation indications for asymptomatic patients, arguing that the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway—ie, short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period, inducibility of atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, and multiple accessory pathway—rather than symptoms, are independent predictors of developing malignant arrhythmia.1-5

These findings contradict those reported by Obeyesekere and colleagues, who concluded that the low SCD incidence rates in patients with WPW syndrome precluded routine invasive screening.19,28 They argued that Pappone and colleagues used malignant arrhythmia as a surrogate marker for death, and that the positive predictive value of a short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period for developing malignant arrhythmia was lower than reported (15% vs 82%, respectively) and that its negative predictive value was 100%.1,19,28 Given these conflicting recommendations, we hope our data elucidates the higher association of adverse outcomes and support considerations for more intensive EPT indications in patients with WPW syndrome.

While our study does not report SCD incidence, it does provide robust and reliable mortality data that suggests a greater association of death within an AF/AFL subgroup. Our findings would support more liberal EPT recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome.1-5,8,9 In this study, the SCA incidence rate was more than double the rate in the AF/AFL cohort (P < .001) and is commonly the initial presenting event in WPW syndrome.9 Even though the reported SCD incidence rate is low in WPW syndrome, our data demonstrated an increased association of death within the AF/AFL cohort. Physicians should consider early risk stratification and ablation to prevent potential recurrent malignant arrhythmia leading to death.1-5,8,9,12,19,20