HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

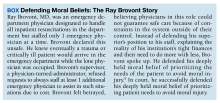

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.