RESULTS

We identified 30 studies; 19 articles did not meet inclusion criteria. The remaining 11 articles were divided into 4 cohorts. Five articles were based on data from the STAR trial, a multicenter study that included adults with moderate-to-severe OSA and inadequate adherence to CPAP.20-24 Four articles used the same patient selection criteria as the STAR trial for a long-term German postmarket study of upper airway stimulation efficacy with OSA.25-28 The third and fourth cohorts each consist of 31 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA with CPAP nonadherence or failure.29,30 The STAR trial included follow-up at 5 years, and the German-postmarket had a follow-up at3 years. The remaining 2 cohorts have 1-year follow-ups.

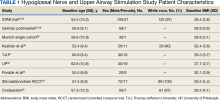

The Scopus review identified 304 studies; 299 did not meet inclusion criteria and 1 was part of the STAR trial.31 The remaining 4 articles were classified as distinct cohorts. Huntley and colleagues included patients from Thomas Jefferson University (TJU) and University of Pittsburgh (UP) academic medical centers.32 The Pordzik and colleagues cohort received implantation at a tertiary medical center, an RCCT, and a 1:1 comparator trial (Table 1).33-35

STAR Trial

This multicenter, prospective, single-group cohort study was conducted in the US, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, and France. The STAR trial included 126 patients who were not CPAP therapy adherent. Patients were excluded if they had AHI < 20 or > 50, central sleep apnea > 25% of total AHI, anatomical abnormalities that prevent effective assessment of upper-airway stimulation, complete concentric collapse of the retropalatal airway during drug-induced sleep, neuromuscular disease, hypoglossal-nerve palsy, severe restrictive or obstructive pulmonary disease, moderate-to-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, severe valvular heart disease, New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, recent myocardial infarction or severe cardiac arrhythmias (within the past 6 months), persistent uncontrolled hypertension despite medication use, active psychiatric illness, or coexisting nonrespiratory sleep disorders that would confound functional sleep assessment. Primary outcome measures included the AHI and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) with secondary outcomes using the ESS, the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), and the percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation < 90%. Of 126 patients who received implantation, 71 underwent an overnight PSG evaluation at 5-year follow-up. Mean (SD) AHI at baseline was reduced with HGNS treatment to from 32.0 (11.8) to 12.4 (16.3). Mean (SD) ESS for 92 participants with 2 measurements declined from 11.6 (5.0) at baseline to 6.9 (4.7) at 5-year follow-up.

The STAR trial included a randomized controlled withdrawal study for 46 patients who had a positive response to therapy to evaluate efficacy and durability of upper airway stimulation. Patients were randomly assigned to therapy maintenance or therapy withdrawal groups for ≥ 1 week. The short-term withdrawal effect was assessed using the original trial outcome measures and indicated that both the withdrawal and maintenance groups showed improvements at 12 months compared with the baseline. However, after the randomized withdrawal, the withdrawal group’s outcome measures deteriorated to baseline levels while the maintenance group showed no change. At 18 months of therapy, outcome measures for both groups were similar to those observed with therapy at 12 months.24 The STAR trial included self-reported outcomes at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months that used ESS to measure daytime sleepiness. These results included subsequent STAR trial reports.20-24,31

The German Postmarket Cohort

This multicenter, prospective, single-arm study used selection criteria that were based on those used in the STAR trial and included patients with moderate-to-severe OSA and nonadherence to CPAP. Patients were excluded if they had a BMI > 35, AHI < 15 or > 65; central apnea index > 25% of total AHI; or complete concentric collapse at the velopharynx during drug-induced sleep. Measured outcomes included AHI, ODI, FOSQ, and ESS. Among the 60 participants, 38 received implantation and a 3-year follow-up. Mean (SD) AHI decreased from 31.2 (13.2) at baseline to 13.1 (14.1) at follow-up, while mean (SD) ESS decreased from 12.8 (5.3) at baseline to 6.0 (3.2) at follow-up.25-28

Munich Cohort

This single-center, prospective clinical trial included patients with AHI > 15 and < 65, central apnea index < 25% of total AHI, and nonadherence to CPAP. Patients were excluded if they had a BMI > 35, anatomical abnormalities that would prevent effective assessment of upper-airway stimulation; all other exclusion criteria matched those used in the STAR trial. Among 31 patients who received implants and completed a 1-year follow-up, mean (SD) AHI decreased from 32.9 (11.2) at baseline to 7.1 (5.9) at follow-up and mean (SD) ESS decreased from 12.6 (5.6) at baseline to 5.9 (5.2) at follow-up.29

Kezirian and Colleagues Cohort

This prospective, single-arm, open-label study was conducted at 4 Australian and 4 US sites. Selection criteria included moderate-to-severe OSA with failure of CPAP, AHI of 20 to 100 with ≥ 15 events/hour occurring in sleep that was non-REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, BMI ≤ 40 (Australia) or ≤ 37 (US), and a predominance of hypopneas (≥ 80% of disordered breathing events during sleep). Patients were excluded if they had earlier upper airway surgery, markedly enlarged tonsils, uncontrolled nasal obstruction, severe retrognathia, > 5% central or mixed apneic events, incompletely treated sleep disorders other than OSA, or a major disorder of the pulmonary, cardiac, renal, or nervous systems. Data were reported for 31 patients whose mean (SD) AHI declined from 45.4 (17.5) at baseline to 25.3 (20.6) at 1-year follow-up and mean (SD) ESS score declined from 12.1 (4.6) at baseline to 7.9 (3.8) 1 year later.30