VTCs connect veterans within the criminal-legal system to needed behavioral health, community, and social services. 31-33,37 VTC participants are commonly connected to case management, behavioral health care, therapeutic journaling programs, and vocational rehabilitation. 38,39 Accordingly, the most common difficulties faced by veterans participating in these courts include substance use, mental health, family issues, anger management and/or aggressive behavior, and homelessness. 36,39 There is limited research on the effectiveness of VTCs. Evidence on their overall effectiveness is largely mixed, though some studies suggest VTC graduates tend to have lower recidivism rates than offenders more broadly or persons who terminate VTC programs prior to completion. 40,41 Other studies suggest that VTC participants are more likely to have jail sanctions, new arrests, and new incarcerations relative to nontreatment court participants. 42 Notably, experimental designs (considered the gold standard in assessing effectiveness) to date have not been applied to evaluate the effectiveness of VTCs; as such, the effectiveness of these programs remains an area in need of continued empirical investigation.

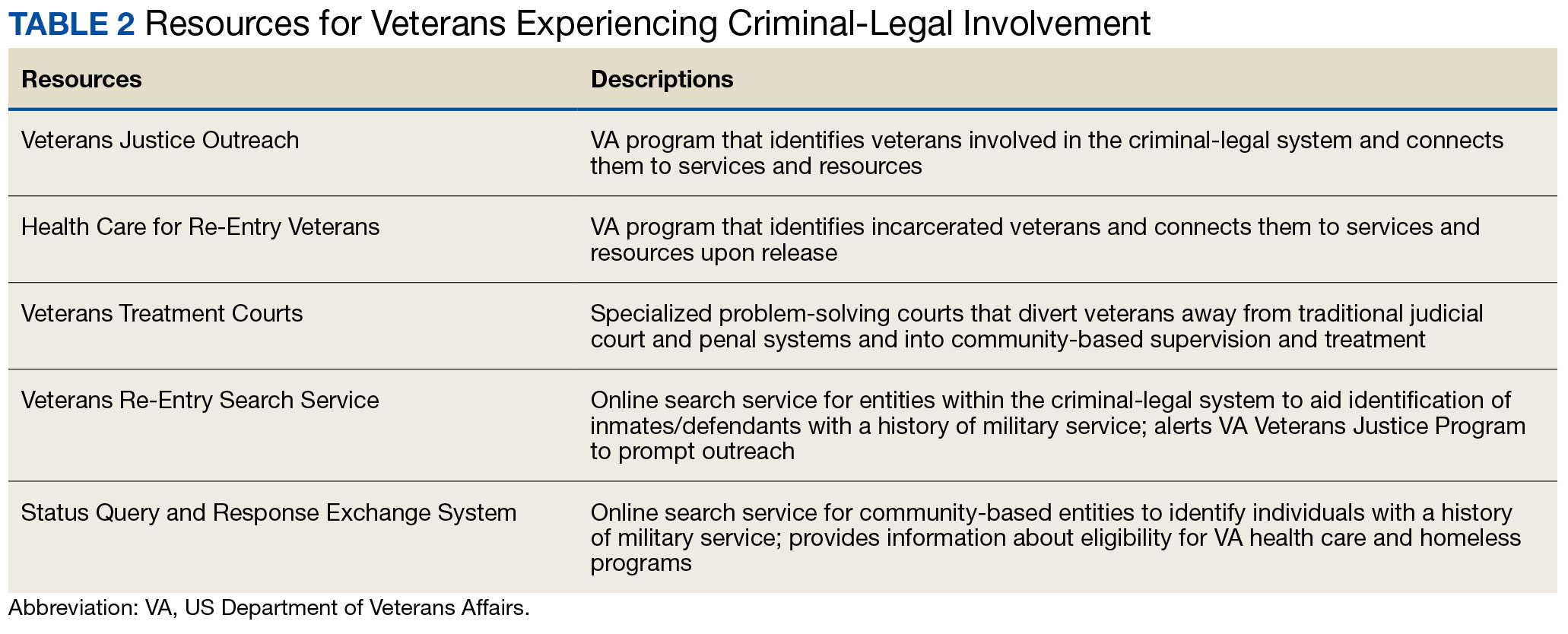

Like all problem-solving courts, VTCs occasionally struggle to connect participating defendants with appropriate care, particularly when encountering structural barriers (eg, insurance, transportation) and/or complex behavioral health needs (eg, personality disorders). 34,43 As suicide rates among veterans experiencing criminal-legal involvement surge (about 150 per 100,000 in 2021, a 10% increase from 2020 to 2021 compared to about 40 per 100,000 and a 1.8% increase among other veterans), efficiency of adequate care coordination is vital. 44 Many VTCs rely on VTC-VA partnerships and collaborations to navigate these difficulties and facilitate connection of participating veterans to needed services. 32-34,45 For example, within the VHA, Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-Entry Veterans (HCRV) specialists assist and bridge the gap between the criminal-legal system (including, but not limited to VTCs) and VA services by engaging veterans involved in the criminal-legal system and connecting them to needed VA-based services (Table 2). Generally, VJO specialists support veterans involved with the front end of the criminallegal system (eg, arrest, pretrial incarceration, or participation in VTCs), while HCRV specialists tend to support veterans transitioning back into the community after a period of incarceration. 46,47 Specific to VTCs, VJO specialists typically serve as liaisons between the courts and VA, coordinating VA services for defendants to fulfill their terms of VTC participation. 46

The historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations from VA-based services has restricted many from accessing VTC programs. 32 Of 17 VTC programs active in Pennsylvania in 2014, only 5 accepted veterans with OTstayH discharges, and 3 required application to and eligibility for VA benefits. 33 Similarly, in national surveys of VTC programs, about 1 in 3 report excluding veterans deemed ineligible for VA services. 35,36 When veterans with OTH discharges have accessed VTC programs, they have historically relied on non-VA, community-based programming to fulfill treatment mandates, which may be less suited to addressing the unique needs of veterans. 48

Veterans who utilize VTCs receive several benefits, namely peer support and mentorship, acceptance into a veteran-centric space, and connection with specially trained staff capable of supporting the veteran through applications for a range of VA benefits (eg, service connection, housing support). 31-33,37 Given the disparate prevalence of OTH discharge characterizations among service members from racial, sexual, and gender minorities and among service members with mental health disorders, exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VTCs solely based on the type of discharge likely contributes to structural inequities among these already underserved groups by restricting access to these potential benefits. Such structural inequity stands in direct conflict with VTC best practice standards, which admonish programs to adjust eligibility requirements to facilitate access to treatment court programs for historically marginalized groups. 49