At PIT, HPACT care was provided during business hours in a flexible model that allowed for walk-in visits. Providers from the existing addiction-focused PACT identified and referred homeless veterans, as well as patients deemed at-risk for becoming homeless. In addition, other homeless veterans who did not have a PCP could be referred through e-consults placed by any VA staff member. If a referred homeless veteran was already enrolled on a PCP’s panel, HPACT facilitated reengagement with the existing provider. Near the end of this data collection period, a peer support specialist also began community outreach to engage both enrolled and potential HPACT patients.

Patient Characteristics

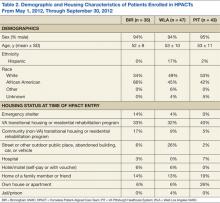

Table 2 presents the demographic and housing characteristics of enrolled HPACT patients at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012, to September 30, 2012. Each site had a similar number of patients (n = 35/47/43 at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Across sites, most patients were male and African American or white. The majority of patients at each site were housed in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs (33%/32%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Fewer patients were unsheltered (on the streets or other places not meant for sleeping), though WLA had the most unsheltered patients (26%) compared with BIR (6%) and PIT (2%). BIR had more patients from emergency shelters (14%) than did the other 2 sites (4% at WLA and 0% at PIT). PIT had the most domiciled patients in houses/apartments (26%, compared with 6% each at BIR and WLA), but who were at risk for homelessness.

Table 3 summarizes the diagnoses and VA health care use patterns of these cohorts. In the first week of HPACT care, WLA addressed the most acute medical conditions (81% of patients had≥ 1 common condition), followed by BIR (54%) and PIT (23%). Among chronic conditions, chronic pain was diagnosed in 51% of patients at BIR, 30% of patients at WLA, and 12% of patients at PIT. Hepatitis C diagnoses were most common at WLA (36%), similar at PIT (33%), and lower at BIR (17%). Overall, chronic medical diagnoses were most common among patients at BIR (91%), followed by WLA (85%), and PIT (60%).

Among mental health diagnoses, mood disorders were the most prevalent across sites (49%/55%/42% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), followed by posttraumatic stress disorder (17%/21%/9% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). WLA had more patients with psychosis (19%) than did the other 2 sites (7% at PIT and 0% at BIR). Overall, mental illness was common among HPACT patients across sites (60%/72%/72% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively).

Health care use in the 6 months before HPACT enrollment differed between sites. BIR and PIT had similar rates of ED/urgent care use (46% and 47% sought care over the prior 6 months, respectively), but WLA had the highest rate (62%). However, inpatient admission rates were lowest at WLA (13%) and again similar at BIR (23%) and PIT (26%). BIR patients had the most VA primary care exposure before HPACT entry (71% obtained primary care in the past 6 months), followed by WLA (38%) and PIT (18%). Mental health specialty care was also highest at BIR (60%), followed by PIT (56%), then WLA (39%)

Table 4 presents the prevalence of ATOD abuse or dependence among HPACT patients in the6 months before clinic enrollment. The most commonly misused substances were alcohol (60%/35%/44% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), tobacco (71%/47%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), and cocaine (37%/19%/23% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). PIT had the highest percentages of patients with opioid misuse (21%), followed by BIR (9%) and WLA (6%). Overall, these disorders were prevalent across sites, highest at BIR (94%) and similar at WLA (72%) and PIT (67%).

DISCUSSION

In this case report of early HPACT implementation, strikingly different models of homeless-focused primary care at the geographically distinct facilities were found. The lack of a gold standard primary care medical home for homeless persons—compounded by contrasting local contextual features—led to distinct clinic designs. BIR capitalized on primary care needs among veterans who previously sought housing and relied on the available space within an operating primary care clinic. As WLA already offered primary care for homeless veterans that was colocated with mental health services, the HPACT at this site was devised as an after-hours clinic colocated with the ED.11 At PIT, an existing primary care team with addiction expertise expanded its role to include a focus on homelessness, without needing new space or staff.

The initial HPACT patient cohorts likely reflected these contrasting clinic structures. That is, at WLA, the higher rates of unsheltered patients, prevalence of acute medical conditions and psychotic disorders, and greater ED use was likely driven by ED colocation. The physical location of this site’s HPACT may also speak to greater future decreases in ED use. At BIR, the use of a dedicated HPACT community outreach worker likely led to greater recruitment from emergency shelters. However, the clinic mainly recruited veterans who had previously engaged in VA mainstream primary care services and individuals with ATOD use. At PIT, higher rates of psychotherapy were likely facilitated by the HPACT’s placement within an addiction treatment setting, which may favor psychosocial rehabilitation. The distinctly higher rate of patients with opioid misuse at PIT likely paralleled the ATOD expertise of its providers and/or buprenorphine availability.