Evaluation of oral antineoplastic agent (OAN) adherence patterns have identified correlations between nonadherence or over-adherence and poorer disease-related outcomes. Multiple studies have focused on imatinib use in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) due to its continuous, long-term use. A study by Ganesan and colleagues found that nonadherence to imatinib showed a significant decrease in 5-year event-free survival between 76.7% of adherent participants compared with 59.8% of nonadherent participants.1 This study found that 44% of patients who were adherent to imatinib achieved complete cytogenetic response vs only 26% of patients who were nonadherent. In another study of imatinib for CML, major molecular response (MMR) was strongly correlated with adherence and no patients with adherence < 80% were able to achieve MMR.2 Similarly, in studies of tamoxifen for breast cancer, < 80% adherence resulted in a 10% decrease in survival when compared to those who were more adherent.3,4

In addition to the clinical implications of nonadherence, there can be a significant cost associated with suboptimal use of these medications. The price of a single dose of OAN medication may cost as much as $440.5

The benefits of multidisciplinary care teams have been identified in many studies.6,7 While studies are limited in oncology, pharmacists provide vital contributions to the oncology multidisciplinary team when managing OANs as these health care professionals have expert knowledge of the medications, potential adverse events (AEs), and necessary monitoring parameters.8 In one study, patients seen by the pharmacist-led oral chemotherapy management program experienced improved clinical outcomes and response to therapy when compared with preintervention patients (early molecular response, 88.9% vs 54.8%, P = .01; major molecular response, 83.3% vs 57.6%, P = .06).9 During the study, 318 AEs were reported, leading to 235 pharmacist interventions to ameliorate AEs and improve adherence.

The primary objective of this study was to measure the impact of a pharmacist-driven OAN renewal clinic on medication adherence. The secondary objective was to estimate cost-savings of this new service.

Methods

Prior to July 2014, several limitations were identified related to OAN prescribing and monitoring at the Richard L. Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Indianapolis, Indiana (RLRVAMC). The prescription ordering process relied primarily on the patient to initiate refills, rather than the prescriber OAN prescriptions also lacked consistency for number of refills or quantities dispensed. Furthermore, ordering of antineoplastic products was not limited to hematology/oncology providers. Patients were identified with significant supply on hand at the time of medication discontinuation, creating concerns for medication waste, tolerability, and nonadherence.

As a result, opportunities were identified to improve the prescribing process, recommended monitoring, toxicity and tolerability evaluation, medication reconciliation, and medication adherence. In July of 2014, the RLRVAMC adopted a new chemotherapy order entry system capable of restricting prescriptions to hematology/oncology providers and limiting dispensed quantities and refill amounts. A comprehensive pharmacist driven OAN renewal clinic was implemented on September 1, 2014 with the goal of improving long-term adherence and tolerability, in addition to minimizing medication waste.

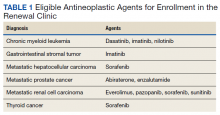

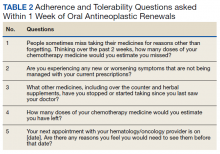

Patients were eligible for enrollment in the clinic if they had a cancer diagnosis and were concomitantly prescribed an OAN outlined in Table 1. All eligible patients were automatically enrolled in the clinic when they were deemed stable on their OAN by a hematology/oncology pharmacy specialist. Stability was defined as ≤ Grade 1 symptoms associated with the toxicities of OAN therapy managed with or without intervention as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03. Once enrolled in the renewal clinic, patients were called by an oncology pharmacy resident (PGY2) 1 week prior to any OAN refill due date. Patients were asked a series of 5 adherence and tolerability questions (Table 2) to evaluate renewal criteria for approval or need for further evaluation. These questions were developed based on targeted information and published reports on monitoring adherence.10,11 Criteria for renewal included: < 10% self-reported missed doses of the OAN during the previous dispensing period, no hospitalizations or emergency department visits since most recent hematology/oncology provider appointment, no changes to concomitant medication therapies, and no new or worsening medication-related AEs. Patients meeting all criteria were given a 30-day supply of OAN. Prescribing, dispensing, and delivery of OAN were facilitated by the pharmacist. Patient cases that did not meet criteria for renewal were escalated to the hematology/oncology provider or oncology clinical pharmacy specialist for further evaluation.

Study Design and Setting

This was a pre/post retrospective cohort, quality improvement study of patients enrolled in the RLRVAMC OAN pharmacist renewal clinic. The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board (IRB) by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Research and Development Department.

Study Population

Patients were included in the preimplementation group if they had received at least 2 prescriptions of an eligible OAN. Therapy for the preimplementation group was required to be a monthly duration > 21 days and between the dates of September 1, 2013 and August 31, 2014. Patients were included in the postimplementation group if they had received at least 2 prescriptions of the studied OANs between September 1, 2014 and January 31, 2015. Patients were excluded if they had filled < 2 prescriptions of OAN; were managed by a non-VA oncologist or hematologist; or received an OAN other than those listed in Table 1.

Data Collection

For all patients in both the pre- and postimplementation cohorts, a standardized data collection tool was used to collect the following via electronic health record review by a PGY2 oncology resident: age, race, gender, oral antineoplastic agent, refill dates, days’ supply, estimated unit cost per dose cancer diagnosis, distance from the RLRVAMC, copay status, presence of hospitalizations/ED visits/dosage reductions, discontinuation rates, reasons for discontinuation, and total number of current prescriptions. The presence or absence of dosage reductions were collected to identify concerns for tolerability, but only the original dose for the preimplementation group and dosage at time of clinic enrollment for the postimplementation group was included in the analysis.

Outcomes and Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome was medication adherence defined as the median medication possession ratio (MPR) before and after implementation of the clinic. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who were adherent from before implementation to after implementation and estimated cost-savings of this clinic after implementation. MPR was used to estimate medication adherence by taking the cumulative day supply of medication on hand divided by the number of days on therapy.12 Number of days on therapy was determined by taking the difference on the start date of the new medication regimen and the discontinuation date of the same regimen. Patients were grouped by adherence into one of the following categories: < 0.8, 0.8 to 0.89, 0.9 to 1, and > 1.1. Patients were considered adherent if they reported taking ≥ 90% (MPR ≥ 0.9) of prescribed doses, adopted from the study by Anderson and colleagues.12 A patient with an MPR > 1, likely due to filling prior to the anticipated refill date, was considered 100% adherent (MPR = 1). If a patient switched OAN during the study, both agents were included as separate entities.

A conservative estimate of cost-savings was made by multiplying the RLRVAMC cost per unit of medication at time of initial prescription fill by the number of units taken each day multiplied by the total days’ supply on hand at time of therapy discontinuation. Patients with an MPR < 1 at time of therapy discontinuation were assumed to have zero remaining units on hand and zero cost savings was estimated. Waste, for purposes of cost-savings, was calculated for all MPR values > 1. Additional supply anticipated to be on hand from dose reductions was not included in the estimated cost of unused medication.

Descriptive statistics compared demographic characteristics between the pre- and postimplementation groups. MPR data were not normally distributed, which required the use of nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests to compare pre- and postMPRs. Pearson χ2 compared the proportion of adherent patients between groups while descriptive statistics were used to estimate cost savings. Significance was determined based on a P value < .05. IBM SPSS Statistics software was used for all statistical analyses. As this was a complete sample of all eligible subjects, no sample size calculation was performed.