Discussion

This project created a successful program to screen veterans for psychosocial distress and triage them to appropriate services. During the project, patients in VA-outpatient oncology clinics reported significant cancer-related distress due to baseline psychosocial needs, changes in emotional and physical functioning, logistical and financial challenges of receiving cancer care, and lack of instrumental support.23

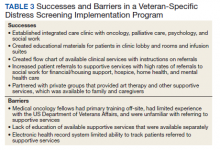

Staff education supported successful buy-in, development and implementation of supportive oncology programs. We used a combination of in-service trainings, online trainings, and handouts to provide evidence for distress screening.24 Highlighting the evidence-base that demonstrates how cancer-related distress screening improves cancer and quality of life outcomes helped to address physician reluctance to accept the additional requirements needed to address veterans’ psychosocial needs and care concerns. To increase buy-in and collaboration among team members and foster heightened understanding between providers and patients, we recommend creating accessible education for all staff levels.

One specific area of education we focused on was primary palliative care, which includes the core competencies of communication and symptom management recommended for generalists and specialists of all disciplines.25 Program staff supported oncology fellows in developing their primary palliative care skills by being available to discuss basic symptom management and communication issues. VA cancer care programs could benefit from ongoing palliative care education of oncology staff to facilitate primary palliative care as well as earlier integration of secondary palliative care when needed.26 Secondary palliative care or care provided directly by the palliative care team assists with complex symptom management or communication issues. For these needs, oncology fellows were encouraged to refer to either the palliative care staff available in one of the half-day clinics or to the outpatient palliative care clinic. As a unique strength, the VA allows veterans to receive concurrent cancer-directed therapy and hospice care, which enables earlier referrals to hospice care and higher quality end-of-life care and emphasizes the need for primary palliative care in oncology.27,28

Integrating supportive oncology team members, such as licensed clinical social worker and psychology interns, was successful. This was modeled on the VA PACT, which focuses on prevention, health promotion, coordination and chronic disease management.29 Social determinants of health have a major impact on health outcomes especially in veteran-specific and African American populations, making screening for distress critical.30-32 The VA Office of Health Equity actively addresses health inequities by supporting initiation of screening programs for social determinants of health, including education, employment, exposure to abuse and violence, food insecurity, housing instability, legal needs, social isolation, transportation needs, and utility needs. This is especially needed for African-American individuals who are not only more likely to experience cancer, but also more likely to be negatively impacted by the consequences of cancer diagnosis/treatment, such as complications related to one’s job security, access to care, adverse effects, and other highly distressing needs.33,34

Our program found that veterans with cancer often had concerns associated with food and housing insecurity, transportation and paying for medication or medical care, and screening allowed health care providers to detect and address these social determinants of health through referrals to VA and community-specific programs. Social workers integrated into VA cancer clinics are uniquely equipped to coordinate distress screening and support continuity of care by virtue of their training, connections to preexisting VA supportive services, and knowledge of community resources. This model could be used in other VA specialty clinics serving veterans with chronic illness and those with high levels of physical frailty.35

Our ability to roll out distress screening was scaffolded by technological integration into existing VA systems (eg, screening results in CPRS and electronic referrals). Screening procedures could have been even more efficient with improved technology (Table 3). For example, technological limitations made it challenging to easily identify patients due for screening, requiring a cumbersome process of tracking, collecting and entering patients’ paper forms. Health care providers seeking to develop a distress screening program should consider investing in technology that allows for identification of patients requiring screening at a predetermined interval, completion of screening via tablet or personal device, integration of screening responses into the electronic health record, and automatic generation of notifications to the treating physician and appropriate support services.

We also established partnerships with community cancer support groups to offer both referral pathways and in-house programming. Veterans’ cancer care programs could benefit from identifying and securing community partnerships to capitalize on readily available low-cost or no-cost options for supportive oncology in the community. Further, as was the case in our program, cancer support centers may be willing to collaborate with VA hospitals to provide services on site (eg, support groups, art therapy). This would extend the reach of these supportive services while allowing VA employees to address the extensive psychosocial needs of individual veterans.

Conclusions

Veterans with cancer benefited from enhanced screening and psychosocial service availability, similar to a PCMHI model. Robust screening programs helped advocate for veterans dealing with the effects of poverty through identification of need and referral to existing VA programs and services quickly and efficiently. Providing comprehensive care within ambulatory cancer clinics can address cancer-related distress and any potential barriers to care in real time. VA hospitals typically offer an array of supportive services to address veterans’ psychosocial needs, yet these services tend to be siloed. Integrated referrals can help to resolve such access barriers. Since many veterans with burdensome cancers are not able to see their VA primary care physician regularly, offering comprehensive care within medical oncology ensures complete and integrated care that includes psychosocial screening.

We believe that this program is an example of a mechanism for oncologists and palliative care clinicians to integrate their care in a way that identifies needs and triages services for vulnerable veterans. As colleagues have written, “it is fundamental to our commitment to veterans that we ensure comparable, high quality care regardless of a veteran’s gender, race, or where they live.”34 Health care providers may underestimate the extensive change a cancer diagnosis can have on a patient’s quality of life. Cancer diagnosis and treatment have a large impact on all individuals, but this impact may be greater for individuals in poverty due to inability to work from home, inflexible work hours, and limited support structures. By creating screening programs with psychosocial integration in oncology clinics such as we have described, we hope to improve access to more equitable care for vulnerable veterans.