Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic cancers, accounting for 65% of all hepatic cancers.1 Among all cancers, HCC is one of the fastest growing causes of death in the United States, and the rate of new HCC cases are on the rise over several decades.2 There are many risk factors leading to HCC, including alcohol use, obesity, and smoking. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a significant risk.1

The pathogenesis of HCV-induced carcinogenesis is mediated by a unique host-induced immunologic response. Viral replication induces production of inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon (IFN), and oxidative stress on hepatocytes, resulting in cell injury, death, and regeneration. Repetitive cycles of cellular death and regeneration induce fibrosis, which may lead to cirrhosis.3 Hence, early treatment of HCV infection and achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) may lead to decreased incidence and mortality associated with HCC.

Treatment of HCV infection has become more effective with the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) leading to SVR in > 90% of patients compared with 40 to 50% with IFN-based treatment.4,5 DAAs have been proved safe and highly effective in eradicating HCV infection even in patients with advanced liver disease with decompensated cirrhosis.6 Although achieving SVR indicates a complete cure from chronic HCV infection, several studies have shown subsequent risk of developing HCC persists even after successful HCV treatment.7-9 Some studies show that using DAAs to achieve SVR in patients with HCV infection leads to a decreased relative risk of HCC development compared with patients who do not receive treatment.10-12 But data on HCC risk following DAA-induced SVR vs IFN-induced SVR are somewhat conflicting.

Much of the information regarding the association between SVR and HCC has been gleaned from large data banks without accounting for individual patient characteristics that can be obtained through full chart review. Due to small sample sizes in many chart review studies, the impact that SVR from DAA therapy has on the progression and severity of HCC is not entirely clear. The aim of our study is to evaluate the effect of HCV treatment and SVR status on overall survival (OS) in patients with HCC. Second, we aim to compare survival benefits, if any exist, among the 2 major HCV treatment modalities (IFN vs DAA).

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of patients at Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee to determine whether treatment for HCV infection in general, and achieving SVR in particular, makes a difference in progression, recurrence, or OS among patients with HCV infection who develop HCC. We identified 111 patients with a diagnosis of both HCV and new or recurrent HCC lesions from November 2008 to March 2019 (Table 1). We divided these patients based on their HCV treatment status, SVR status, and treatment types (IFN vs DAA).

The inclusion criteria were patients aged > 18 years treated at the Memphis VAMC who have HCV infection and developed HCC. Exclusion criteria were patients who developed HCC from other causes such as alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatitis B virus infection, hemochromatosis, patients without HCV infection, and patients who were not established at the Memphis VAMC. This protocol was approved by the Memphis VAMC Institutional Review Board.

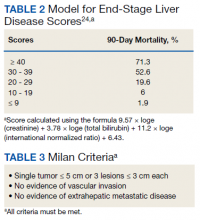

HCC diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Diseases codes (9th revision: 155 and 155.2; 10th revision: CD 22 and 22.9). We also used records of multidisciplinary gastrointestinal malignancy tumor conferences to identify patient who had been diagnosed and treated for HCV infection. We identified patients who were treated with DAA vs IFN as well as patients who had achieved SVR (classified as having negative HCV RNA tests at the end of DAA treatment). We were unable to evaluate Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging since this required documented performance status that was not available in many patient records. We selected cases consistent with both treatment for HCV infection and subsequent development of HCC. Patient data included age; OS time; HIV status HCV genotype; time and status of progression to HCC; type and duration of treatment; and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. Disease status was measured using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (Table 2), Milan criteria (Table 3), and Child-Pugh score (Table 4).