Results

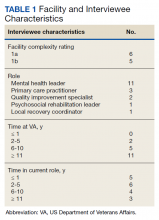

The 170 participants had a mean (SD) age of 62.1 (4.6) years and were 70.6% male (Table 1). Hyperlipidemia was the most prevalent cardiac risk factor with almost 70% of participants on a statin. There was no incidence of ischemic ASCVD during follow-up, although 1 participant was later diagnosed with lung cancer after evaluation of suspicious pulmonary findings on ECG-gated CT. CAC was identified on both scan types in 126 participants; however, LDCT was discordant with gated CT in identifying CAC in 24 subjects (P < .001).

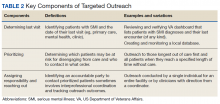

The correlation between CAC scores on ECG-gated CT and LDCT was 0.945 (P < .001) and the concordance was 0.643, indicating moderate agreement between CAC scores on the 2 different scans (Figure 1). Median CAC scores were significantly higher on ECG-gated CT when compared with LDCT (107.5 vs 48.1 Agatston units, respectively; P < .05). Table 2 shows the CAC score characteristics for both scan types. The κ statistic for agreement between categorical CAC scores on ECG-gated CT compared with LDCT was 0.49 (SEκ= 0.05; 95% CI, -0.73-1.71), and the weighted κ statistic was 0.71, indicating moderate to substantial agreement between the 2 scans using the specified cutoff points. The Bland-Altman analysis presented a mean bias of 111.45 Agatston units, with limits of agreement between -268.64 and 491.54, as shown in Figure 2, suggesting that CAC scores on ECG-gated CT were, on average, about 111 units higher than those on LDCT. Finally, there were 24 participants with CAC seen on ECG-gated CT but none identified on LDCT (P < .001); of this cohort 20 were already on a statin, and of the remaining 4 individuals, 1 met statin criteria based on a > 20% ASCVD risk score alone (regardless of CAC score), 1 with an intermediate risk score met statin criteria based on CAC score reporting, 1 did not meet criteria due to a low-risk score, and the last had no reportable ASCVD risk score.

In the study, there were 80 participants with reportable borderline to intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk scores (5% ≤ 10-year ASCVD risk < 20%), 49 of which were taking a statin. Of the remaining 31 participants not on a statin, 19 met statin criteria after CAC was identified on ECG-gated CT (of these 18 also had CAC identified on LDCT). Subsequently, the number of participants who met statin criteria after additional CAC reporting (on ECG-gated CT and LDCT) was statistically significant (P < .001 and P < .05, respectively). Of the 49 participants on a statin, only 1 individual no longer met statin criteria due to a CAC score < 1 on gated CT.

Discussion

In this study population of recruited MHS beneficiaries, there was a strong correlation and moderate to substantial agreement between CAC scores calculated from LDCT and conventional ECG-gated CT. The number of nonstatin participants who met statin criteria and would have benefited from additional CAC score reporting was statistically significant as compared to their statin counterparts who no longer met the criteria.

CAC screening using nongated CT has become an increasingly available and consistently reproducible means for stratifying ASCVD risk and guiding statin therapy in individuals with equivocal ASCVD risk scores.24-26 As has been demonstrated in previous studies, our study additionally highlights the effective use of LDCT in not only identifying CAC, but also in beneficially impacting statin decisions in the high-risk smoking population.24-26 Our results also showed LDCT missed CAC in participants, the majority of which were already on a statin, and only 1 nonstatin individual benefited from additional CAC reporting. CAC scoring on LDCT should be an adjunct, not a substitute, for ASCVD risk stratification to help guide statin management.25,27

Our results may provide cost considerate implications for preventive CAC screening. While TRICARE covers the cost of ECG-gated CT for MHS beneficiaries, the same is not true of most nonmilitary insurance providers. Concerns about cancer risk from radiation exposure may also lead to hesitation about receiving additional CTs in the smoking population. Since the LCS population already receives annual LDCT, these scans can also be used for CAC scoring to help primary care professionals risk stratify their patients, as has been previously shown.28-31 Clinicians should consider implementing CAC scoring with annual LDCT scans, which would curtail further risks and expenses from CAC-specified scans.

Although CAC is scored visually and routinely reported in the body of LDCT reports at our facility, this is not a universal practice and was performed in only 44% of subjects with known CAC by a previous study.32 In 2007, there were 600,000 CAC scoring scans and > 9 million routine chest CTs performed in the United States.33 Based on our results and the growing consensus in the existing literature, CAC scoring on nongated CT is not only valid and reliable, but also can estimate ASCVD risk and subsequent mortality.34-36 Routine chest CTs remain an available resource for providing additional ASCVD risk stratification.

As we demonstrated, median CAC scores on LDCT were on average significantly lower than those from gated CT. This could be due to slice thickness variability between the GE and Siemens scanners or CAC progression between the time of the retrospective LDCT and prospective ECG-gated CT. Aside from this potential limitation, LDCT has been shown to have a high level of agreement with gated CT in predicting CAC, both visually and by the Agatston technique.37-39 Our results further support previous recommendations of utilizing CAC score categories when determining ASCVD risk from LDCT and that establishing scoring cutoff points warrants further development for potential standardization.37-39 Readers should be mindful that LDCT may still be less sensitive and underestimate low CAC levels and that ECG-gated CT may occasionally be more optimal in determining ASCVD risk when considering the negative predictive value of CAC.40