Your next patient is a 67-year-old Medicare beneficiary with corticosteroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Despite 4 months of maximally dosed mesalamine, his colitis flares with prednisone taper below 20 mg daily. Hepatitis B serologies and tuberculin skin test were negative 10 months ago. Which of the following do you recommend?

A. Steroid-sparing therapy initiation

B. Repeat latent tuberculosis screening in anticipation of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

C. Bone loss assessment

D. Pneumococcal vaccination

E. Tobacco use screening

All of the above may be appropriate for optimal clinical care, but only two (C and E) will impact your bottom line when using the new GI Measures Set to report quality measures through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). For the 75.1% of physicians who have not heard of – or don’t know much about – MIPS,1 the gastroenterology world will come to know it as the dominant of two Quality Payment Program (QPP) tracks introduced as part of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Starting in 2017, the QPP handles quality measure reporting and reimbursement adjustments based on the quality and cost of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. MIPS replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), Value-Based Payment Modifier, and electronic health record Meaningful Use programs that previously executed these tasks.Quality measure reporting is a costly undertaking, with medical practices spending an average of 15.1 hours per physician per week ($40,069 per physician annually) dealing with external quality measures.2 How did this expensive alphabet soup of quality measure reporting arise and how does it impact inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care?

Why are IBD quality measures needed?

There is substantial variation in care provided to IBD patients. Examples include geographic variation in rates of prolonged corticosteroid3 and biologic therapy use (Figure 1),4 hospitalization, and colectomy.5 IBD experts and community gastroenterologists manage IBD differently.6,7 This variation reflects more than mere “art of medicine” stylistic differences. Patient, provider, and system-level factors contribute to practice variation, including the heterogeneity of IBD phenotypes, lack of knowledge about best practices, insufficient evidence on which to base treatment decisions, and variable access to care. Variation likely indicates resource underuse, overuse, and misuse and may be a marker of poor quality care.8,9 Closing the gap between current and ideal IBD care – by reducing unnecessary variation – may reduce suboptimal outcomes, preventable complications, care costs, and waste. Financially incentivized quality metrics have been proposed as a performance improvement and standardization strategy.What makes a good quality measure?

Quality must be defined and measured before it can be improved. This is easier said than done, especially for IBD where a gold standard in “ideal care” is ill defined and continually evolving as new research emerges. Nonetheless, hundreds of health care quality measures have been proposed. Desirable quality measure attributes should satisfy three broad categories: importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.10 Quality measures should address relevant and important aspects of health that are highly prevalent and for which evidence indicates a need for improvement. There should be strong evidence supporting the beneficial impact of adhering to a given measure.

From a practicality standpoint, measures should relate to actions that are under the control of the providers whose performance is being measured. Measures should also be parsimonious with a goal of minimizing the number of measures needed to adequately represent performance in a given area.11 More simply stated, a good quality measure reflects consensus about a minimally acceptable level of care that applies broadly to all patients.Quality measures are commonly classified as process measures or outcome measures. Process measures (“doing the right thing”) are steps taken by providers in the care of an individual patient. These often derive from evidence-based best practices. Outcome measures (“having the desired result”) identify what happens to patients as a result of care received.8 Outcome measures may be more meaningful, but there are limitations in using them to study quality of IBD care. For example, factors beyond physician control affect patient outcomes and long delays may exist between care decisions and subsequent outcomes (e.g., surgery, malnutrition).8

What IBD quality measures already exist?

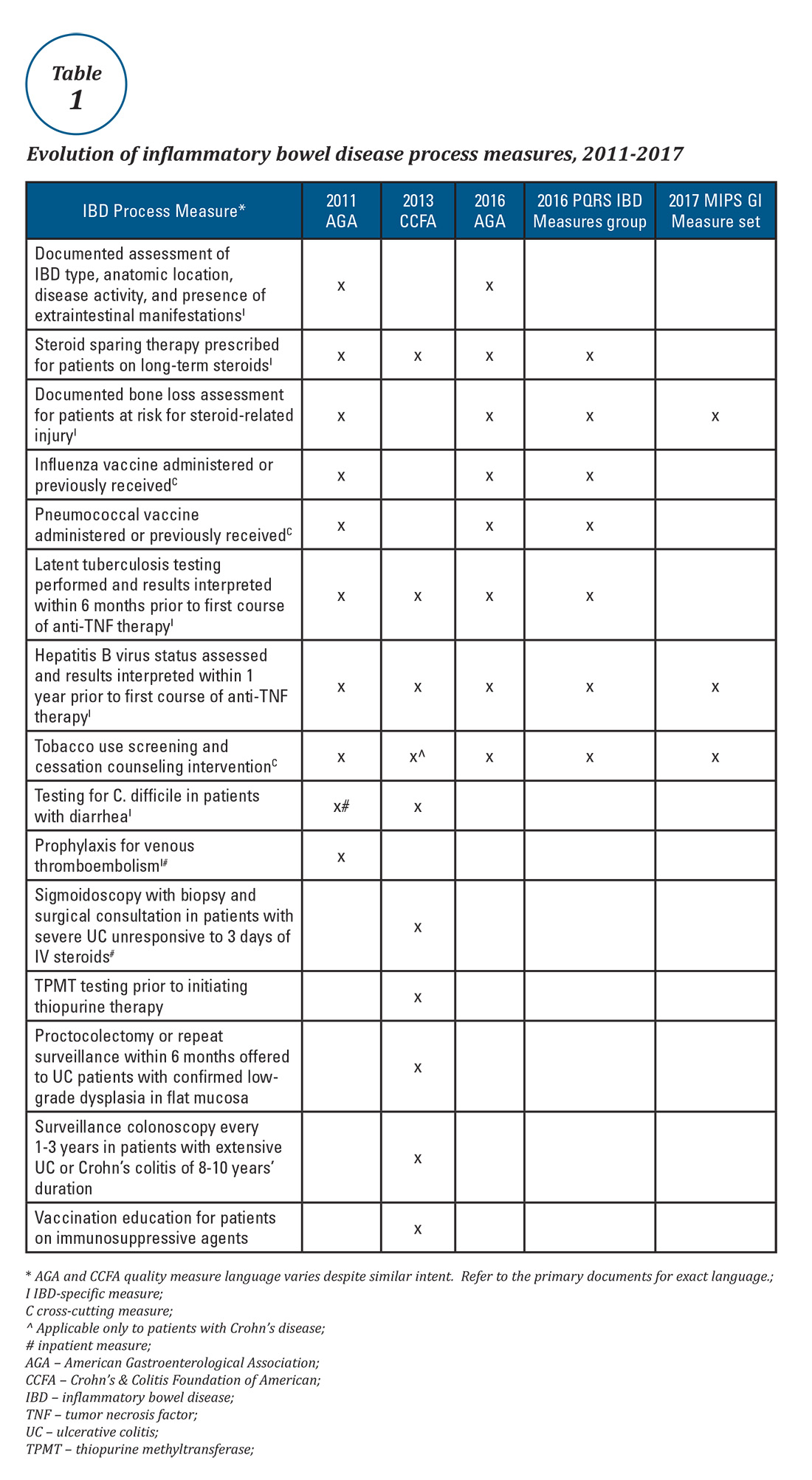

Expert panels from the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) produced IBD quality measure sets comprising mostly process measures (Table 1). The original 10 AGA measures released in 2011 address aspects of disease assessment, treatment, complication prevention, and health care maintenance.12 They include seven IBD-specific measures, three cross-cutting measures – defined by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as being broadly applicable across multiple clinical settings – and two inpatient measures. A major goal of the AGA measures was to facilitate quality reporting to the former PQRS program.