Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.

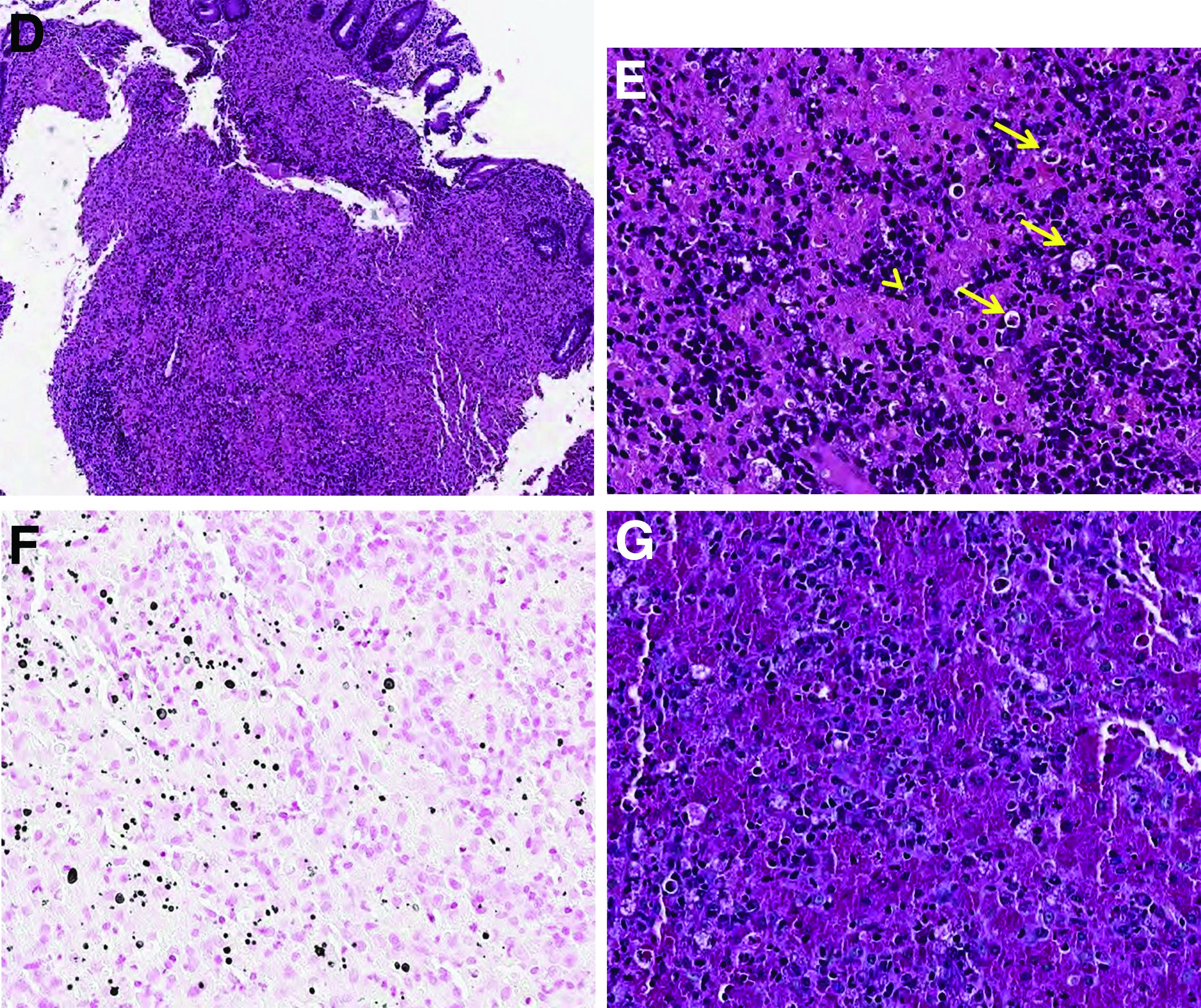

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens revealed nodular mixed inflammatory cells and infiltration of the epithelioid histiocytes in lamina propria (Figure D; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 40×). The histiocytes showed foamy and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure E, arrow) and some of them had a targetoid appearance (Figure E, arrow head; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). Von Kossa stains highlighted the targetoid structures in the histiocytes (Figure F, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies). The granular cytoplasm of the histiocytes was positive on periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure G). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with colonic malakoplakia.

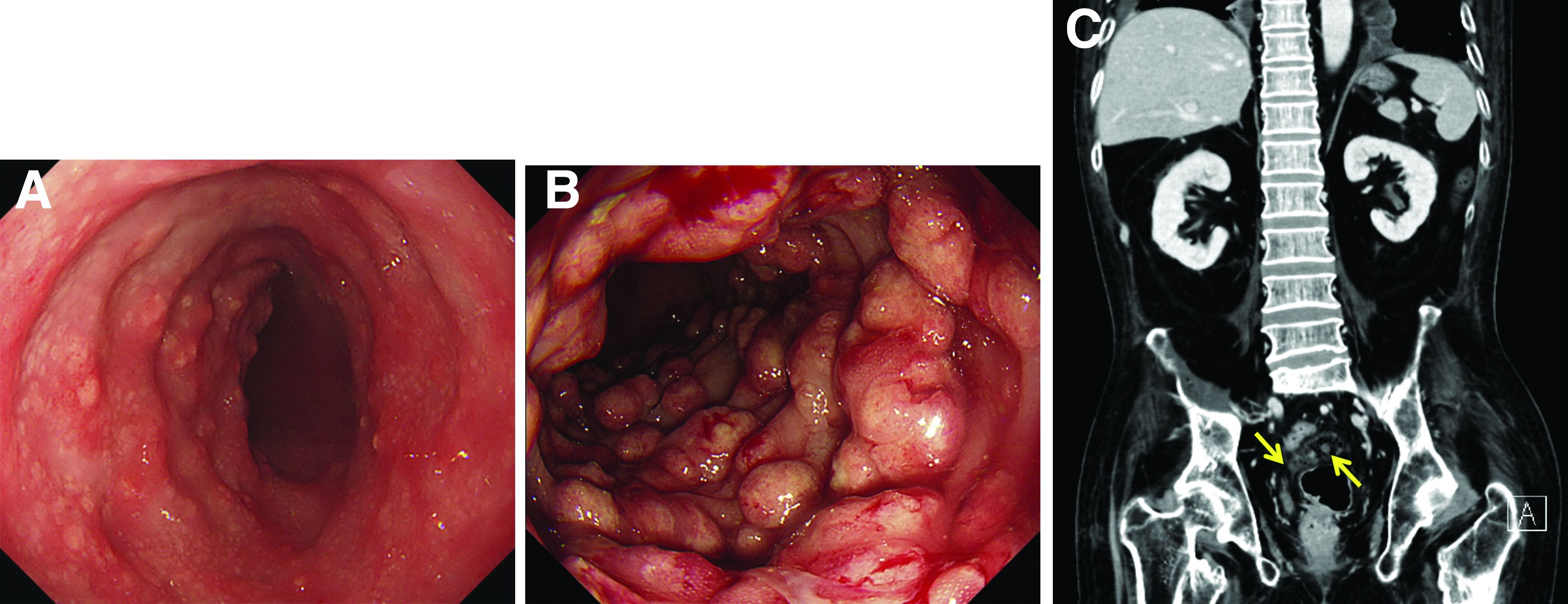

Malakoplakia is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease. It most commonly affects the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, but may occur at any anatomic site. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract are seen most frequently in the rectum, sigmoid, and right colon.1 It is diagnosed by the characteristic histologic feature of accumulated histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing basophilic inclusions, consistent with Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia are unclear, it seems to originate from an acquired defect in the intracellular destruction of phagocytosed bacteria, usually associated with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium.2 It can have various causes, such as immunosuppression, malignant neoplasms, systemic diseases, and genetic diseases. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic to malaise, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and intestinal obstruction. Granulomatous reaction of malakoplakia generates the endoscopic appearance of lesions, which ranges from plaques to nodules and yellow-brown masses. In the early stage, malakoplakia commonly presents as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques endoscopically, as seen in our case (Figure A). As the disease progresses in the later stage, malakoplakia presents as raised, grey to tan polypoid lesions of various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area, as seen in our case (Figure B).3 Owing to this endoscopic morphology, colonic malakoplakia may be misdiagnosed as atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, and metastatic carcinoma. To date, the natural course of malakoplakia of the colon is unclear, and no guidelines for treatment, treatment methods, duration of treatment, or surveillance are currently available. However, treatment of malakoplakia is essential to reduce immunosuppression and includes antibiotics with intracellular action and choline agonists that replenish the decreased cyclic 3’, 5’-guanosine monophosphate levels. In summary, although malakoplakia of the colon is very rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of polypoid colonic lesions, especially in immunocompromised or malnourished patients.

References

1. Cipolletta L et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar;41(3):255-8.

2. Berney T et al. Transpl Int. 1999;12(4):293-6.

3. Weinrach DM et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Oct;128(10):e133-4.