Gout is an extremely painful arthritis initiated by innate immune responses to monosodium urate crystals that accumulate in affected joints and surrounding tissues. As a result, gout is characterized by painful arthritis flares followed by intervening periods of disease quiescence. Over time, gout can lead to chronic pain, disability, and tophi. Nearly 10% of those aged > 65 years report having gout. The overall prevalence in the U.S. population approaches 4%.1

Gout treatment has 2 overarching goals: alleviating the pain and inflammation caused by acute gout attacks and long-term management that is focused on lowering serum urate (sUA) levels to reduce the risk of future attacks. Alleviating the pain and inflammation of an acute attack is often complicated by patient characteristics, namely, other chronic health conditions that frequently accompany gout, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Patients with gout tend to be older and have multiple comorbidities that require the use of many medications.2 Because the VA patient population tends to be older, acute gout and attendant complications of treatment are an important consideration for VA health care providers (HCPs).

Recently, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) released management recommendations for gout, including those for the treatment of acute gout.3 The ACR recommends 3 first-line therapies, but limited guidance is provided for deciding among therapies. This article briefly reviews the relevant ACR recommendations and details important comorbidity and concomitant medication considerations in the treatment of acute gout.

Acute Gout Characteristics

Acute gout attacks are characterized by a rapid onset and escalation with joint pain typically peaking within 24 hours of attack onset. An acute attack often begins to remit after 5 to 12 days without intervention, but complete resolution may take longer in some patients.4 In one study, at 24 hours after attack onset, 16% of patients on placebo had > 50% reduction in pain compared with 70% that had no recovery at all.5 By 48 hours, one-third of patients on placebo achieved a 50% reduction in pain.6

Acute gout attacks are most commonly monoarticular, although 10% to 40% can involve ≥ 2 joints.7 The first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is the initial site of involvement in about 50% of cases and is eventually observed in the majority of patients with gout (Figure 1).7 Other commonly affected joints include the midfoot, ankle, knee, wrist, elbow, and fingers. Most patients still reach peak pain within 24 hours with pain remitting predictably over 1 to 2 weeks. Chronic or variable intensity pain is more common among those with long-standing disease, polyarticular gout, or tophi.Treatment Recommendations

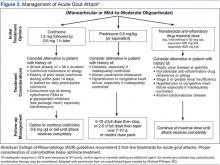

Therapy for acute gout attacks aims to reduce pain and promote a full, early resolution. The ACR recommends pharmacologic therapy as first-line treatment with adjunctive topical ice and rest as needed.3 Typically, monotherapy is appropriate if the individual is experiencing mild-to-moderate pain affecting ≤ 2 joints of any size. Severe pain or attacks affecting multiple joints may benefit from initial combination therapy. Three first-line therapies are available: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, colchicine, or systemic glucocorticoids (Figure 2).

Few studies compare the efficacy of first-line therapeutic categories. There are no clinical trials directly comparing colchicine with NSAIDs or colchicine with glucocorticoids. No difference in mean reduction of pain and no differences in adverse events (AEs) were shown in a trial that compared glucocorticoids with NSAIDs.8 Thus, without further study, treatment choices made by HCPs are often guided by factors other than the existence of robust evidence.

Treatment with NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors should be initiated at the approved dose and continued until the gout attack has completely resolved. In one study, 73% of patients had pain reduction of ≥ 50% when taking NSAIDs relative to only 27% of patients on placebo.8 All available NSAIDs are considered effective, but only 3 NSAIDs are specifically approved for treatment of acute gout (naproxen, indomethacin, and sulindac). There is no evidence supporting one NSAID as being more effective than another; evidence fails to show a meaningful difference.8 Limited evidence indicates that selective COX-2 inhibitors, including celexocib, have similar efficacy as nonselective NSAIDs but may have fewer AEs, driven in part by fewer gastrointestinal (GI) events (6% vs 16% for GI events).8

Colchicine has long been used as prophylaxis for acute gout attacks and has been endorsed for the treatment of acute attacks. Recent evidence suggests that colchicine initially dosed at 1.2 mg followed by a single 0.6-mg dose 1 hour later is as effective with fewer AEs compared with a traditional regimen of 1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg every hour for up to 6 hours.5 About 40% of patients have 50% pain reduction within 24 hours and a 40% absolute risk reduction in AEs on this low-dose regimen. The efficacy of colchicine relative to other therapies is poorly defined, especially for patients presenting longer after attack onset. The ACR guidelines recommend colchicine only if treatment is initiated within 36 hours of attack onset, but this is based solely on expert consensus. Likewise, the above trial for low-dose colchicine did not provide information about dosing beyond the first 6 hours, leaving little guidance for follow-up treatment of residual pain beyond the 32 hours reported.5 Traditionally, one 0.6-mg dose is provided every 12 to 24 hours.3