This article has been adapted from an article originally published in Current Psychiatry (http://currentpsychiatry.com):Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(10):29-32,35-40,e6.

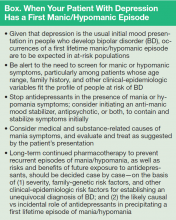

When a known depressed patient newly develops signs of mania or hypomania, a cascade of diagnostic and therapeutic questions ensues: Does the event “automatically” signify the presence of bipolar disorder (BD), or could manic symptoms be secondary to another underlying medical problem, a prescribed antidepressant or non-psychotropic medication, or illicit substances?

Even more questions confront the clinician: If mania symptoms are nothing more than an adverse drug reaction, will they go away by stopping the presumed offending agent? Or do symptoms always indicate the unmasking of a bipolar diathesis? Should anti-manic medication be prescribed immediately? If so, which one(s) and for how long? How extensive a medical or neurologic workup is indicated?

And how do you differentiate ambiguous hypomania symptoms (irritability, insomnia, agitation) from other phenomena, such as akathisia, anxiety, and overstimulation?

In this article, we present an overview of how to approach and answer these key questions, so that you can identify, comprehend, and manage manic symptoms that arise in the course of your patient’s treatment for depression (Box).

Does Disease Exist on a Unipolar-Bipolar Continuum.

There has been a resurgence of interest in Kraepelin’s original notion of mania and depression as falling along a continuum, rather than being distinct categories of pathology. True bipolar mania has its own identifiable epidemiology, familiality, and treatment, but symptomatic shades of gray often pose a formidable diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

For example, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) relaxed its definition of “mixed” episodes of BD to include subsyndromal mania features in unipolar depression. When a patient with unipolar depression develops a full, unequivocal manic episode, there usually isn’t much ambiguity or confusion about initial management: assure a safe environment, stop any antidepressants, rule out drug- or medically induced causes, and begin an acute anti-manic medication.

Next steps can, sometimes, be murkier:

- Formulate a definitive, overarching diagnosis

- Provide psycho-education

- Forecast return to work or school

- Discuss prognosis and likelihood of relapse

- Address necessary lifestyle modifications (eg, sleep hygiene, elimination of alcohol and illicit drug use)

- Determine whether indefinite maintenance pharmacotherapy is indicated—and, if so, with which medication(s).

A Diagnostic Formulation Isn’t Always Black and White

Ms. J, age 56, a medically healthy woman, has a 10-year history of depression and anxiety that has been treated effectively for most of that time with venlafaxine,

225 mg/d. The mother of 4 grown children, Ms. J has worked steadily for > 20 years as a flight attendant for an international airline.

Today, Ms. J is brought by ambulance from work to the emergency department in a paranoid and agitated state. The admission follows her having e-blasted airline corporate executives with a voluminous manifesto that she worked on around the clock the preceding week, in which she explained her bold ideas to revolutionize the airline industry, under her leadership.

Ms. J’s family history is unremarkable for psychiatric illness.