Discussion

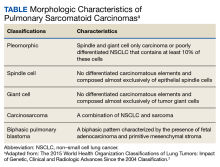

An interdisciplinary discussion regarding the diagnosis considered the clinical features of the patient along with the imaging characteristics. The histological examination demonstrating sarcomatoid features with the supporting immunohistochemistry that confirmed both mesenchymal and epithelioid presence and was used to make the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC).

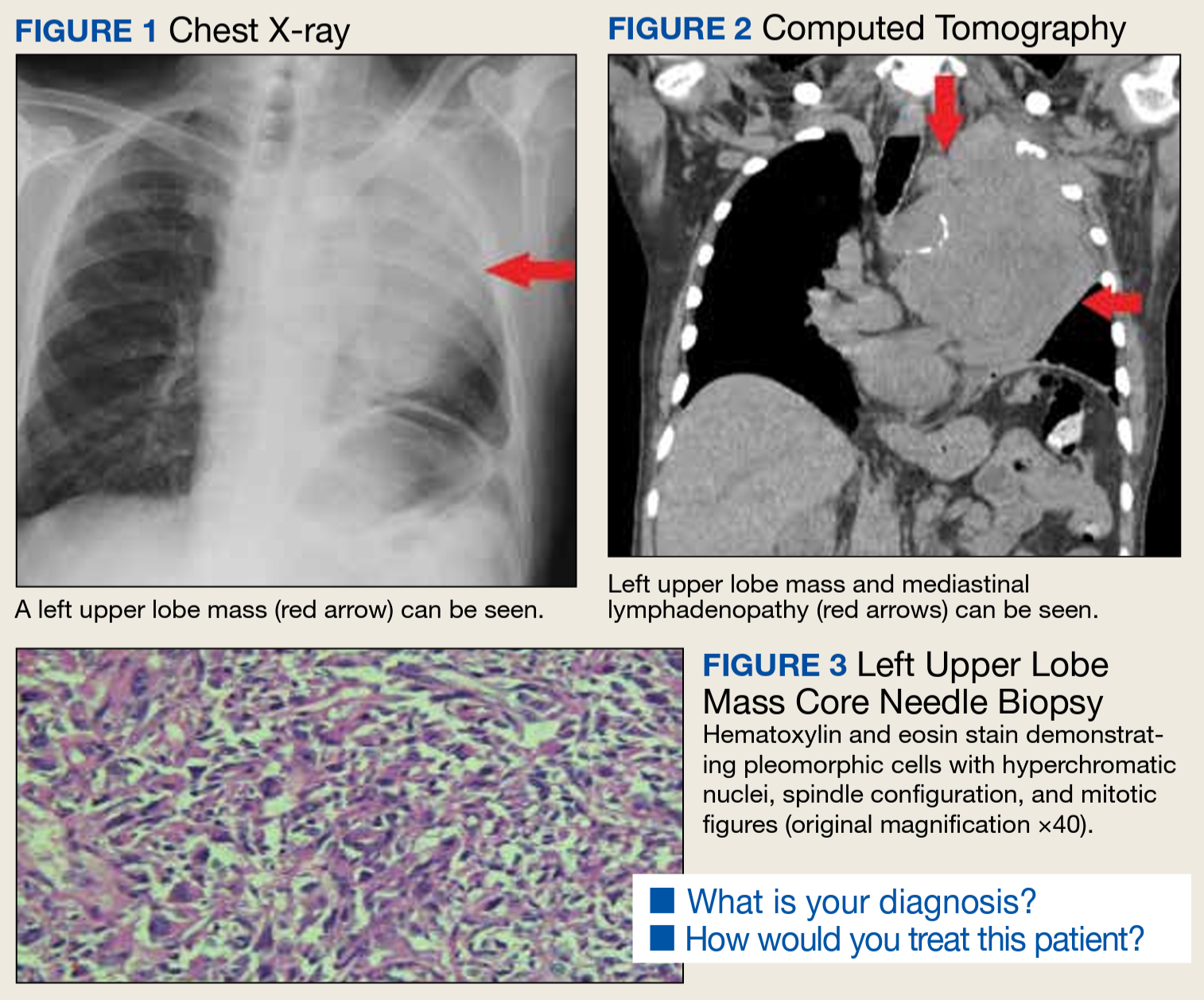

PSC is a very rare aggressive subtype of poorly differentiated non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). This tumor is clinically characterized by tumor cells with molecular, histological, and cytological properties of epithelial and mesenchymal tumors, distinguishing it from other types of NSCLC. PSC has a sarcoma-like differentiation (spindle and/or giant cell) or a component of sarcoma (malignant bone, cartilage, or skeletal muscle).1-5 The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified PSC based on morphological characteristics (Table).The incidence of PSC ranges between 0.1% and 0.4% of all lung malignancies.1,4-7 PSC usually occurs in older men whose weight is moderate to heavy and who smoke. PSC appears to have an upper lobe predilection; also, these tumors tend to be bulky with invasive tendency, early recurrence, and systemic metastases. PSC frequently involves the adjacent lung, chest wall, diaphragm, pericardium, and other tissues.1-5 The source of the sarcoma component of the PSC remains uncertain. However, prior research suggests that it is associated with a clonal evolution that induces epidermal and mesenchymal tumor histological characteristics.1,8,9 The tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition may induce transformation of the carcinoma component of PSC to into a sarcoma component. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with the PSC high risk for invasiveness and induces metastasis sites, such as the esophagus, colon, rectum, kidneys, and the common sites of NSCLC.

The most common symptoms include productive cough, chest congestion, and chest pain.1,7 In view of PSC’s clinical presentation and imaging, numerous differential diagnoses should be considered, such as sarcomatoid carcinomas, primary or secondary metastatic sarcomas, malignant melanoma, and pleural mesothelioma.6,10

The tumor is initially identified by a chest CT, confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry. Several biomarkers are useful for diagnosis and classification of an undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Those biomarkers help to understand the tumor pathobiology, to select the therapeutic regimen, and to predict the patient’s outcome. Although immunohistochemical staining of epithelial and mesenchymal markers can be helpful, a reliable diagnosis requires a precise histopathological examination. This is often difficult on small biopsy samples, such as fine-needle aspiration, as all the histological elements of PSC required to make the correct evaluation may not be present. Adequate sampling to generate a considerable number of histological slides is essential for an accurate diagnosis, which can be reached only with surgical resection.5

Due to rarity, rapid progression, short survival, and heterogeneous pathological qualities, PSC has been difficult to formulate treatment recommendations. Compared with other histological subtypes of NSCLC, PSC is more aggressive and has a poor prognosis. Survival time on average is about 13.3 months due to early metastasis, lower than other types of NSCLC. The greatest overall survival (OS) benefit has been shown with surgery in early-stage operable PSC, which remains the standard of care. Because most patients with PSC present in the advanced stage, they lose their opportunity for curative surgery. Auxiliary methods of treatment include radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Prior studies have shown that systemic chemotherapy efficacy has varied, some showing no OS benefit; others showing a modest benefit. It has also been noted that advanced-stage PSC has minimal response to chemotherapy. Further larger prospective studies are needed to outline the efficacy and role of systemic chemotherapy and other therapeutic agents, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy.1,4,11-13 However, two-thirds of patients are not sensitive to conventional chemotherapy. In comparison with other types of NSCLC, PSC carries a poor prognosis even in early-stage disease or if tumor metastasis is present. Therefore, further research on novel treatment options is needed to improve long-term survival.1,3-8

Conclusions

PSC is diagnostically challenging because it is rare and has an aggressive progression. Identification of this tumor requires knowledge of histological criteria to identify their subtypes. Immunohistochemistry has an important role in the classification and to rule out differential diagnoses, including metastatic spread. Nevertheless, a reliable diagnosis requires precise histopathological examination, reached with surgical resection. Therefore, a detailed history, physical examination, systematic investigation, and correlation with chest imaging are needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

Our case highlights the importance of keeping this rare, aggressive tumor as part of the differential diagnosis. In view of its natural history, heterogeneity, and low incidence, published cases of PSC are limited. Thus, further investigation could optimize rapid identification and treatment options.