User login

Policy in Clinical Practice: Medicare Advantage and Observation Hospitalizations

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 73-year-old man presents to the emergency department with sepsis secondary to community-acquired pneumonia. The patient requires supplemental oxygen and is started on intravenous antibiotics. His admitting physician expects he will need more than two nights of hospital care and suggests that inpatient status, rather than outpatient (observation) status, would be appropriate under Medicare’s “Two-Midnight Rule.” The physician also suspects the patient may need a brief stay in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) following the mentioned hospitalization and notes that the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan (Table) and wonders if the Two-Midnight Rule applies. Further, she questions whether Medicare’s “Three-Midnight Rule” for SNF benefits will factor in the patient’s discharge planning.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Since the 1970s, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has allowed enrollees to receive their Medicare benefits from privately managed health plans through the so-called Medicare Advantage programs. CMS contracts with commercial insurers who, in exchange for a set payment per Medicare enrollee, “accept full responsibility (ie, risk) for the costs of their enrollees’ care.”1 Over the past 20 years the percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees has nearly doubled nationwide, from 18% to 34%, and is projected to grow even further to 42% by 2028.2,3 The reasons beneficiaries choose to enroll in Medicare Advantage over Traditional Medicare have yet to be thoroughly studied; ease of enrollment and plan administration, as well as lower deductibles, copays, and out-of-pocket maximums for in-network services, are thought to be some of the driving factors.

The federal government has asserted two goals for the development of Medicare Advantage: beneficiary choice and economic efficiency.1 Medicare Advantage plans must be actuarially equal to Traditional Medicare but do not have to cover services in precisely the same way. Medicare Advantage plans may achieve cost savings through narrower networks, strict control of access to SNF services and acute care inpatient rehabilitation, and prior authorization requirements, the latter of which has received recent congressional attention.4,5 On the other hand, many Medicare Advantage plans offer dental, fitness, optical, and caregiver benefits that are not included under Traditional Medicare. Beneficiaries can theoretically compare the coverage and costs of Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage programs and make informed choices based on their individualized needs. The second stated goal for the Medicare Advantage option assumes that privately managed plans provide care at lower costs compared with CMS; this assumption has yet to be confirmed with solid data. Indeed, a recent analysis comparing the overall costs of Medicare Advantage to those of Traditional Medicare concluded that Medicare Advantage costs CMS more than Traditional Medicare,6 perhaps in part due to risk adjustment practices.7

POLICY IN PRACTICE

There are a number of areas of uncertainty regarding the specifics of how Medicare Advantage plans work, including Medicare Advantage programs’ use of outpatient (observation) stays. CMS has tried to provide guidance to healthcare organizations and clinicians regarding the appropriate use of inpatient hospitalizations for patients with Traditional Medicare, including the implementation of the Two-Midnight Rule in 2013. According to the rule, clinicians should place inpatient admission orders when they reasonably expect a patient’s care to extend across two midnights.8 Such admission decisions are subject to review by Medicare contractors and Quality Improvement Organizations.

In contrast, Medicare Advantage plans which enter into contracts with specific healthcare systems are not required to abide by CMS’ guidelines for the Two-Midnight Rule.9 When Medicare Advantage firms negotiate contracts with individual hospitals and healthcare organizations, CMS has been clear that such contracts are not required to include the Two-Midnight Rule when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10 Instead, in these instances, Medicare Advantage plans often use proprietary decision tools containing clinical criteria, such as Milliman Care Guidelines or InterQual, and/or their own plan’s internal criteria as part of the decision-making process to grant inpatient or outpatient (observation) status. More importantly, CMS has stated that for hospitals and healthcare systems that do not contract with Medicare Advantage programs, the Two-Midnight Rule should apply when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10

Implications for Patients

Currently, there are no data available to compare between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional medicine beneficiaries in terms of the frequency of observation use and out-of-pocket cost for observation stays. As alluded to in the patient’s case, the use of outpatient (observation) status has implications for a patient’s posthospitalization SNF benefit. Under Traditional Medicare, patients must be hospitalized for three consecutive inpatient midnights in order to qualify for the SNF benefit. Time spent under outpatient (observation) status does not count toward this three-day requirement. Interestingly, some Medicare Advantage programs have demonstrated innovation in this area, waiving the three inpatient midnight requirement for their beneficiaries;11 there is evidence, however, that compared with their Traditional Medicare counterparts, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are admitted to lower quality SNFs.12 The posthospitalization consequences of an inpatient versus outpatient (observation) status determination for a Medicare Advantage beneficiary is thus unclear, further complicating the decision-making process for patients when it comes to choosing a Medicare policy, and for providers when it comes to choosing an admission status.

Implications for Clinicians and Healthcare Systems

After performing an initial history and physical exam, if a healthcare provider determines that a patient requires hospitalization, an order is placed to classify the stay as inpatient or outpatient (observation). For beneficiaries with Traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan that has not contracted with the hospital, clinicians should follow the Two-Midnight Rule for making this determination. For contracted Medicare Advantage, the rules are variable. Under Medicare’s Conditions of Participation, hospitals and healthcare organizations are required to have utilization management (UM) programs to assist physicians in making appropriate admission decisions. UM reviews can happen at any point during or after a patient’s stay, however, and physicians may have to make decisions using their best judgment at the time of admission without real-time input from UM teams.

Outpatient (observation) care and the challenges surrounding appropriate status orders have complicated the admission decision. In one study of 2014 Traditional Medicare claims, almost half of outpatient (observation) stays contained a status change.13 Based on a recent survey of hospitalist physicians, about two-thirds of hospitalists report at least monthly requests from patients to change their status.14 Hospital medicine physicians report that these requests “can severely damage the therapeutic bond”14 between provider and patient because the provider must assign status based on CMS rules, not patient request.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could improve the current system in one of two ways. First, CMS could require that all Medicare Advantage plans follow the same polices as Traditional Medicare policies regarding the Two- and Three-Midnight Rules. This would eliminate the need for both hospitals and healthcare organizations to dedicate time and resources to negotiating with each Medicare Advantage program and to managing each Medicare Advantage patient admission based on a specific contract. Ideally, CMS could completely eliminate its outpatient (observation) policy so that all hospitalizations are treated exactly the same, classified under the same billing status and with beneficiaries having the same postacute benefit. This would be consistent with the sentiment behind the recent Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) report suggesting that CMS consider counting outpatient midnights toward the three-midnight requirement for postacute SNF care “so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”15

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

The physician in the example above should tell their patient that they will be admitted as an inpatient given her expectation that the patient will need hospitalization for oxygen support, parenteral antibiotics, and evaluation by physical therapy to determine a medically appropriate discharge plan. The physician should document the medical necessity for the admission, specifically her expectation that the patient will require at least two midnights of medically necessary hospital care. If the patient has Traditional Medicare, this documentation, along with the inpatient status order, will fulfill the requirements for an inpatient stay. If the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan, the physician can advise the patient that the plan administrators will ultimately determine if an inpatient stay will be covered or denied.

CONCLUSIONS

In the proposed clinical scenario, the rules determining the patient’s hospitalization status depend on whether the hospital contracts with the patient’s Medicare Advantage plan, and if so, what the contracted criteria are in determining inpatient and outpatient (observation) status. The physician could consider real-time input from the hospital’s UM team, if available. Regardless of UM input, if the physician hospitalizes the patient as an inpatient, the Medicare Advantage plan administrators will make a determination regarding the appropriateness of the admission status, as well as whether the patient qualifies for posthospitalization Medicare SNF benefits (if requested) and, additionally, which SNFs will be covered. If denied, the hospitalist will have the option of a peer-to-peer discussion with the insurance company to overturn the denial. Given the confusion, complexity, and implications presented by this admission status decision-making process, standardization across Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, or a budget-neutral plan to eliminate status distinction altogether, is certainly warranted.

1.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Millbank Q. 2011;89(2):289-332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x.

2. Medicare Advantage. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/.

3. Neuman P, Jacobson G. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163-2172. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089.

4. HR 3107: improving seniors’ timely access to Care Act of 2019. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3107/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22prior+authorization%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1.

5. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield RR, et al. Medicare Advantage control of postacute costs: perspective from stakeholders. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(12):e386-e392.

6. Rooke-Ley H, Broome T, Mostashari F, Cavanaugh S. Evaluating Medicare programs against saving taxpayer dollars. Health Affairs, August 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190813.223707/full/.

7. Office of Inspector General. Billions in estimated Medicare Advantage payments from chart reviews raise concerns. December 2019. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-17-00470.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2019.

8. Fact sheet: two-midnight rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-two-midnight-rule-0.

9. Locke C, Hu E. Medicare’s two-midnight rule: what hospitalists must know. Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/194971/medicares-two-midnight-rule.

10. Announcement of calendar year (CY) 2019 Medicare Advantage capitation rates and Medicare Advantage and part D payment policies and final call letter. Page 206. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2019.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019.

11. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trivedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Aff. 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054.

12. Meyers D, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):78-85. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714.

13. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: Policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

14. The hospital observation care problem: perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/policy-and-advocacy/advocacy-pdf/shms-observation-white-paper-2017. Accessed November 18, 2019.

15. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Solutions to reduce fraud, waste and abuse in HHS programs: OIG’s top recommendations. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/. Accessed November 22, 2019.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 73-year-old man presents to the emergency department with sepsis secondary to community-acquired pneumonia. The patient requires supplemental oxygen and is started on intravenous antibiotics. His admitting physician expects he will need more than two nights of hospital care and suggests that inpatient status, rather than outpatient (observation) status, would be appropriate under Medicare’s “Two-Midnight Rule.” The physician also suspects the patient may need a brief stay in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) following the mentioned hospitalization and notes that the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan (Table) and wonders if the Two-Midnight Rule applies. Further, she questions whether Medicare’s “Three-Midnight Rule” for SNF benefits will factor in the patient’s discharge planning.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Since the 1970s, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has allowed enrollees to receive their Medicare benefits from privately managed health plans through the so-called Medicare Advantage programs. CMS contracts with commercial insurers who, in exchange for a set payment per Medicare enrollee, “accept full responsibility (ie, risk) for the costs of their enrollees’ care.”1 Over the past 20 years the percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees has nearly doubled nationwide, from 18% to 34%, and is projected to grow even further to 42% by 2028.2,3 The reasons beneficiaries choose to enroll in Medicare Advantage over Traditional Medicare have yet to be thoroughly studied; ease of enrollment and plan administration, as well as lower deductibles, copays, and out-of-pocket maximums for in-network services, are thought to be some of the driving factors.

The federal government has asserted two goals for the development of Medicare Advantage: beneficiary choice and economic efficiency.1 Medicare Advantage plans must be actuarially equal to Traditional Medicare but do not have to cover services in precisely the same way. Medicare Advantage plans may achieve cost savings through narrower networks, strict control of access to SNF services and acute care inpatient rehabilitation, and prior authorization requirements, the latter of which has received recent congressional attention.4,5 On the other hand, many Medicare Advantage plans offer dental, fitness, optical, and caregiver benefits that are not included under Traditional Medicare. Beneficiaries can theoretically compare the coverage and costs of Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage programs and make informed choices based on their individualized needs. The second stated goal for the Medicare Advantage option assumes that privately managed plans provide care at lower costs compared with CMS; this assumption has yet to be confirmed with solid data. Indeed, a recent analysis comparing the overall costs of Medicare Advantage to those of Traditional Medicare concluded that Medicare Advantage costs CMS more than Traditional Medicare,6 perhaps in part due to risk adjustment practices.7

POLICY IN PRACTICE

There are a number of areas of uncertainty regarding the specifics of how Medicare Advantage plans work, including Medicare Advantage programs’ use of outpatient (observation) stays. CMS has tried to provide guidance to healthcare organizations and clinicians regarding the appropriate use of inpatient hospitalizations for patients with Traditional Medicare, including the implementation of the Two-Midnight Rule in 2013. According to the rule, clinicians should place inpatient admission orders when they reasonably expect a patient’s care to extend across two midnights.8 Such admission decisions are subject to review by Medicare contractors and Quality Improvement Organizations.

In contrast, Medicare Advantage plans which enter into contracts with specific healthcare systems are not required to abide by CMS’ guidelines for the Two-Midnight Rule.9 When Medicare Advantage firms negotiate contracts with individual hospitals and healthcare organizations, CMS has been clear that such contracts are not required to include the Two-Midnight Rule when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10 Instead, in these instances, Medicare Advantage plans often use proprietary decision tools containing clinical criteria, such as Milliman Care Guidelines or InterQual, and/or their own plan’s internal criteria as part of the decision-making process to grant inpatient or outpatient (observation) status. More importantly, CMS has stated that for hospitals and healthcare systems that do not contract with Medicare Advantage programs, the Two-Midnight Rule should apply when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10

Implications for Patients

Currently, there are no data available to compare between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional medicine beneficiaries in terms of the frequency of observation use and out-of-pocket cost for observation stays. As alluded to in the patient’s case, the use of outpatient (observation) status has implications for a patient’s posthospitalization SNF benefit. Under Traditional Medicare, patients must be hospitalized for three consecutive inpatient midnights in order to qualify for the SNF benefit. Time spent under outpatient (observation) status does not count toward this three-day requirement. Interestingly, some Medicare Advantage programs have demonstrated innovation in this area, waiving the three inpatient midnight requirement for their beneficiaries;11 there is evidence, however, that compared with their Traditional Medicare counterparts, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are admitted to lower quality SNFs.12 The posthospitalization consequences of an inpatient versus outpatient (observation) status determination for a Medicare Advantage beneficiary is thus unclear, further complicating the decision-making process for patients when it comes to choosing a Medicare policy, and for providers when it comes to choosing an admission status.

Implications for Clinicians and Healthcare Systems

After performing an initial history and physical exam, if a healthcare provider determines that a patient requires hospitalization, an order is placed to classify the stay as inpatient or outpatient (observation). For beneficiaries with Traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan that has not contracted with the hospital, clinicians should follow the Two-Midnight Rule for making this determination. For contracted Medicare Advantage, the rules are variable. Under Medicare’s Conditions of Participation, hospitals and healthcare organizations are required to have utilization management (UM) programs to assist physicians in making appropriate admission decisions. UM reviews can happen at any point during or after a patient’s stay, however, and physicians may have to make decisions using their best judgment at the time of admission without real-time input from UM teams.

Outpatient (observation) care and the challenges surrounding appropriate status orders have complicated the admission decision. In one study of 2014 Traditional Medicare claims, almost half of outpatient (observation) stays contained a status change.13 Based on a recent survey of hospitalist physicians, about two-thirds of hospitalists report at least monthly requests from patients to change their status.14 Hospital medicine physicians report that these requests “can severely damage the therapeutic bond”14 between provider and patient because the provider must assign status based on CMS rules, not patient request.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could improve the current system in one of two ways. First, CMS could require that all Medicare Advantage plans follow the same polices as Traditional Medicare policies regarding the Two- and Three-Midnight Rules. This would eliminate the need for both hospitals and healthcare organizations to dedicate time and resources to negotiating with each Medicare Advantage program and to managing each Medicare Advantage patient admission based on a specific contract. Ideally, CMS could completely eliminate its outpatient (observation) policy so that all hospitalizations are treated exactly the same, classified under the same billing status and with beneficiaries having the same postacute benefit. This would be consistent with the sentiment behind the recent Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) report suggesting that CMS consider counting outpatient midnights toward the three-midnight requirement for postacute SNF care “so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”15

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

The physician in the example above should tell their patient that they will be admitted as an inpatient given her expectation that the patient will need hospitalization for oxygen support, parenteral antibiotics, and evaluation by physical therapy to determine a medically appropriate discharge plan. The physician should document the medical necessity for the admission, specifically her expectation that the patient will require at least two midnights of medically necessary hospital care. If the patient has Traditional Medicare, this documentation, along with the inpatient status order, will fulfill the requirements for an inpatient stay. If the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan, the physician can advise the patient that the plan administrators will ultimately determine if an inpatient stay will be covered or denied.

CONCLUSIONS

In the proposed clinical scenario, the rules determining the patient’s hospitalization status depend on whether the hospital contracts with the patient’s Medicare Advantage plan, and if so, what the contracted criteria are in determining inpatient and outpatient (observation) status. The physician could consider real-time input from the hospital’s UM team, if available. Regardless of UM input, if the physician hospitalizes the patient as an inpatient, the Medicare Advantage plan administrators will make a determination regarding the appropriateness of the admission status, as well as whether the patient qualifies for posthospitalization Medicare SNF benefits (if requested) and, additionally, which SNFs will be covered. If denied, the hospitalist will have the option of a peer-to-peer discussion with the insurance company to overturn the denial. Given the confusion, complexity, and implications presented by this admission status decision-making process, standardization across Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, or a budget-neutral plan to eliminate status distinction altogether, is certainly warranted.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 73-year-old man presents to the emergency department with sepsis secondary to community-acquired pneumonia. The patient requires supplemental oxygen and is started on intravenous antibiotics. His admitting physician expects he will need more than two nights of hospital care and suggests that inpatient status, rather than outpatient (observation) status, would be appropriate under Medicare’s “Two-Midnight Rule.” The physician also suspects the patient may need a brief stay in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) following the mentioned hospitalization and notes that the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan (Table) and wonders if the Two-Midnight Rule applies. Further, she questions whether Medicare’s “Three-Midnight Rule” for SNF benefits will factor in the patient’s discharge planning.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Since the 1970s, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has allowed enrollees to receive their Medicare benefits from privately managed health plans through the so-called Medicare Advantage programs. CMS contracts with commercial insurers who, in exchange for a set payment per Medicare enrollee, “accept full responsibility (ie, risk) for the costs of their enrollees’ care.”1 Over the past 20 years the percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees has nearly doubled nationwide, from 18% to 34%, and is projected to grow even further to 42% by 2028.2,3 The reasons beneficiaries choose to enroll in Medicare Advantage over Traditional Medicare have yet to be thoroughly studied; ease of enrollment and plan administration, as well as lower deductibles, copays, and out-of-pocket maximums for in-network services, are thought to be some of the driving factors.

The federal government has asserted two goals for the development of Medicare Advantage: beneficiary choice and economic efficiency.1 Medicare Advantage plans must be actuarially equal to Traditional Medicare but do not have to cover services in precisely the same way. Medicare Advantage plans may achieve cost savings through narrower networks, strict control of access to SNF services and acute care inpatient rehabilitation, and prior authorization requirements, the latter of which has received recent congressional attention.4,5 On the other hand, many Medicare Advantage plans offer dental, fitness, optical, and caregiver benefits that are not included under Traditional Medicare. Beneficiaries can theoretically compare the coverage and costs of Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage programs and make informed choices based on their individualized needs. The second stated goal for the Medicare Advantage option assumes that privately managed plans provide care at lower costs compared with CMS; this assumption has yet to be confirmed with solid data. Indeed, a recent analysis comparing the overall costs of Medicare Advantage to those of Traditional Medicare concluded that Medicare Advantage costs CMS more than Traditional Medicare,6 perhaps in part due to risk adjustment practices.7

POLICY IN PRACTICE

There are a number of areas of uncertainty regarding the specifics of how Medicare Advantage plans work, including Medicare Advantage programs’ use of outpatient (observation) stays. CMS has tried to provide guidance to healthcare organizations and clinicians regarding the appropriate use of inpatient hospitalizations for patients with Traditional Medicare, including the implementation of the Two-Midnight Rule in 2013. According to the rule, clinicians should place inpatient admission orders when they reasonably expect a patient’s care to extend across two midnights.8 Such admission decisions are subject to review by Medicare contractors and Quality Improvement Organizations.

In contrast, Medicare Advantage plans which enter into contracts with specific healthcare systems are not required to abide by CMS’ guidelines for the Two-Midnight Rule.9 When Medicare Advantage firms negotiate contracts with individual hospitals and healthcare organizations, CMS has been clear that such contracts are not required to include the Two-Midnight Rule when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10 Instead, in these instances, Medicare Advantage plans often use proprietary decision tools containing clinical criteria, such as Milliman Care Guidelines or InterQual, and/or their own plan’s internal criteria as part of the decision-making process to grant inpatient or outpatient (observation) status. More importantly, CMS has stated that for hospitals and healthcare systems that do not contract with Medicare Advantage programs, the Two-Midnight Rule should apply when it comes to making hospitalization status decisions.10

Implications for Patients

Currently, there are no data available to compare between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional medicine beneficiaries in terms of the frequency of observation use and out-of-pocket cost for observation stays. As alluded to in the patient’s case, the use of outpatient (observation) status has implications for a patient’s posthospitalization SNF benefit. Under Traditional Medicare, patients must be hospitalized for three consecutive inpatient midnights in order to qualify for the SNF benefit. Time spent under outpatient (observation) status does not count toward this three-day requirement. Interestingly, some Medicare Advantage programs have demonstrated innovation in this area, waiving the three inpatient midnight requirement for their beneficiaries;11 there is evidence, however, that compared with their Traditional Medicare counterparts, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are admitted to lower quality SNFs.12 The posthospitalization consequences of an inpatient versus outpatient (observation) status determination for a Medicare Advantage beneficiary is thus unclear, further complicating the decision-making process for patients when it comes to choosing a Medicare policy, and for providers when it comes to choosing an admission status.

Implications for Clinicians and Healthcare Systems

After performing an initial history and physical exam, if a healthcare provider determines that a patient requires hospitalization, an order is placed to classify the stay as inpatient or outpatient (observation). For beneficiaries with Traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan that has not contracted with the hospital, clinicians should follow the Two-Midnight Rule for making this determination. For contracted Medicare Advantage, the rules are variable. Under Medicare’s Conditions of Participation, hospitals and healthcare organizations are required to have utilization management (UM) programs to assist physicians in making appropriate admission decisions. UM reviews can happen at any point during or after a patient’s stay, however, and physicians may have to make decisions using their best judgment at the time of admission without real-time input from UM teams.

Outpatient (observation) care and the challenges surrounding appropriate status orders have complicated the admission decision. In one study of 2014 Traditional Medicare claims, almost half of outpatient (observation) stays contained a status change.13 Based on a recent survey of hospitalist physicians, about two-thirds of hospitalists report at least monthly requests from patients to change their status.14 Hospital medicine physicians report that these requests “can severely damage the therapeutic bond”14 between provider and patient because the provider must assign status based on CMS rules, not patient request.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could improve the current system in one of two ways. First, CMS could require that all Medicare Advantage plans follow the same polices as Traditional Medicare policies regarding the Two- and Three-Midnight Rules. This would eliminate the need for both hospitals and healthcare organizations to dedicate time and resources to negotiating with each Medicare Advantage program and to managing each Medicare Advantage patient admission based on a specific contract. Ideally, CMS could completely eliminate its outpatient (observation) policy so that all hospitalizations are treated exactly the same, classified under the same billing status and with beneficiaries having the same postacute benefit. This would be consistent with the sentiment behind the recent Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) report suggesting that CMS consider counting outpatient midnights toward the three-midnight requirement for postacute SNF care “so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”15

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

The physician in the example above should tell their patient that they will be admitted as an inpatient given her expectation that the patient will need hospitalization for oxygen support, parenteral antibiotics, and evaluation by physical therapy to determine a medically appropriate discharge plan. The physician should document the medical necessity for the admission, specifically her expectation that the patient will require at least two midnights of medically necessary hospital care. If the patient has Traditional Medicare, this documentation, along with the inpatient status order, will fulfill the requirements for an inpatient stay. If the patient has a Medicare Advantage plan, the physician can advise the patient that the plan administrators will ultimately determine if an inpatient stay will be covered or denied.

CONCLUSIONS

In the proposed clinical scenario, the rules determining the patient’s hospitalization status depend on whether the hospital contracts with the patient’s Medicare Advantage plan, and if so, what the contracted criteria are in determining inpatient and outpatient (observation) status. The physician could consider real-time input from the hospital’s UM team, if available. Regardless of UM input, if the physician hospitalizes the patient as an inpatient, the Medicare Advantage plan administrators will make a determination regarding the appropriateness of the admission status, as well as whether the patient qualifies for posthospitalization Medicare SNF benefits (if requested) and, additionally, which SNFs will be covered. If denied, the hospitalist will have the option of a peer-to-peer discussion with the insurance company to overturn the denial. Given the confusion, complexity, and implications presented by this admission status decision-making process, standardization across Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, or a budget-neutral plan to eliminate status distinction altogether, is certainly warranted.

1.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Millbank Q. 2011;89(2):289-332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x.

2. Medicare Advantage. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/.

3. Neuman P, Jacobson G. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163-2172. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089.

4. HR 3107: improving seniors’ timely access to Care Act of 2019. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3107/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22prior+authorization%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1.

5. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield RR, et al. Medicare Advantage control of postacute costs: perspective from stakeholders. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(12):e386-e392.

6. Rooke-Ley H, Broome T, Mostashari F, Cavanaugh S. Evaluating Medicare programs against saving taxpayer dollars. Health Affairs, August 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190813.223707/full/.

7. Office of Inspector General. Billions in estimated Medicare Advantage payments from chart reviews raise concerns. December 2019. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-17-00470.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2019.

8. Fact sheet: two-midnight rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-two-midnight-rule-0.

9. Locke C, Hu E. Medicare’s two-midnight rule: what hospitalists must know. Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/194971/medicares-two-midnight-rule.

10. Announcement of calendar year (CY) 2019 Medicare Advantage capitation rates and Medicare Advantage and part D payment policies and final call letter. Page 206. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2019.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019.

11. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trivedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Aff. 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054.

12. Meyers D, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):78-85. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714.

13. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: Policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

14. The hospital observation care problem: perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/policy-and-advocacy/advocacy-pdf/shms-observation-white-paper-2017. Accessed November 18, 2019.

15. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Solutions to reduce fraud, waste and abuse in HHS programs: OIG’s top recommendations. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/. Accessed November 22, 2019.

1.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Millbank Q. 2011;89(2):289-332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x.

2. Medicare Advantage. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/.

3. Neuman P, Jacobson G. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163-2172. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089.

4. HR 3107: improving seniors’ timely access to Care Act of 2019. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3107/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22prior+authorization%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1.

5. Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield RR, et al. Medicare Advantage control of postacute costs: perspective from stakeholders. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(12):e386-e392.

6. Rooke-Ley H, Broome T, Mostashari F, Cavanaugh S. Evaluating Medicare programs against saving taxpayer dollars. Health Affairs, August 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190813.223707/full/.

7. Office of Inspector General. Billions in estimated Medicare Advantage payments from chart reviews raise concerns. December 2019. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-17-00470.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2019.

8. Fact sheet: two-midnight rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-two-midnight-rule-0.

9. Locke C, Hu E. Medicare’s two-midnight rule: what hospitalists must know. Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/194971/medicares-two-midnight-rule.

10. Announcement of calendar year (CY) 2019 Medicare Advantage capitation rates and Medicare Advantage and part D payment policies and final call letter. Page 206. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2019.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019.

11. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trivedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Aff. 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054.

12. Meyers D, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):78-85. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714.

13. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: Policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

14. The hospital observation care problem: perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/policy-and-advocacy/advocacy-pdf/shms-observation-white-paper-2017. Accessed November 18, 2019.

15. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Solutions to reduce fraud, waste and abuse in HHS programs: OIG’s top recommendations. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/. Accessed November 22, 2019.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Next Steps for Next Steps: The Intersection of Health Policy with Clinical Decision-Making

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to nextsteps@hospitalmedicine.org.

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to nextsteps@hospitalmedicine.org.

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine introduced the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series in 20151 as a companion to the popular Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do For No Reason™ series2 that was introduced in October in the same year. Both series were created in partnership with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and were designed in the spirit of the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s mission to “promote conversations between clinicians and patients” in choosing care supported by evidence that minimizes harm, including avoidance of unnecessary treatments and tests.3 The Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series extends these principles as a forum for manuscripts that focus on translating value-based concepts into daily operations, including systems-level care delivery redesign initiatives, payment model innovations, and analyses of relevant policies or practice trends.

INITIAL EXPERIENCE

Since its inception, 16 Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscripts have been published, encompassing a wide range of topics such as postacute care transitions,4 the role of hospital medicine practice within accountable care organizations (ACOs),5 and quality and value at end-of-life.6

NEXT STEPS WITH NEXT STEPS

Few physicians receive health policy training.7,8 Hospital medicine practitioners are a core component of the workforce, driving change and value-based improvements at almost every inpatient facility across the country. Regardless of their background or experience, hospital medicine practitioners must interface with legislation, regulation, and other policies every day while providing patient care. Intentional, value-based improvements are more likely to succeed if those providing direct patient care understand health policies, particularly the effects of those policies on transactional, point-of-care decisions.

We are pleased to expand the Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value series to include articles exploring health policy implications at the bedside. These articles will use common clinical scenarios to illuminate health policies most germane to hospital medicine practitioners and present applications of the policies as they relate to value at the level of patient–provider interactions. Each article will present a clinical scenario, explain key policy terms, address implications of specific policies in clinical practice, and propose how those policies can be improved (Appendix). Going forward, Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value manuscript titles will include either “Policy in Clinical Practice” or “Improving Healthcare Value” to better establish a connection to the series and distinguish between the two article types.

The first Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value—Implications of Health Policy on Clinical Decision-Making manuscript appears in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.9 As is the current practice for Choosing Wisely®: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value, authors are requested to send series editors a 500-word precis for review to ensure topic suitability before submission of a full manuscript. The precis, as well as any questions pertaining to the new series, can be directed to nextsteps@hospitalmedicine.org.

The authors thank the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation for supporting this series.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

1. Horwitz L, Masica A, Auerbach A. Introducing choosing wisely: Next steps in improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3): 187-189.

2. Feldman L. Choosing wisely: Things we do for no reasons. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

3. Choosing wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed July 8, 2019.

4. Conway S, Parekh A, Hughes A, et al. Next steps in improving healthcare value: Postacute care transitions: Developing a skilled nursing facility collaborative within an academic health system. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):174-177. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3117.

5. Li J, Williams M. Hospitalist value in an ACO world. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):272-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2965.

6. Fail R, Meier D. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: Opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896.

7. Fry C, Buntin M, Jain S. Medical schools and health policy: Adapting to the changing health care system. NEJM Catalyst, 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/medical-schools-health-policy-research/. Accessed July 10, 2019.

8. For doctors-in-training, a dose of health policy helps the medicine go down. National Public Radio (NPR), 2016. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/06/09/481207153/for-doctors-in-training-a-dose-of-health-policy-helps-the-medicine-go-down. Accessed July 10, 2019.

9. Kaiksow FA, Powell WR, Ankuda CK, et al. Policy in clinical practice: Medicare advantage and observation hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):6-8. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3364.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Papules on trunk

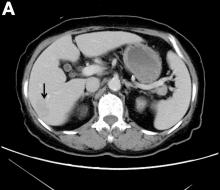

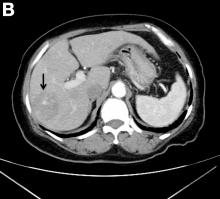

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

SABCS research changes practice

In this edition of “How I Will Treat My Next Patient,” I highlight two presentations from the recent San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) that will likely change practice for some breast cancer patients – even before the ball drops in Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

Residual cancer burden

Researchers reported a multi-institutional analysis of individual patient-level data on 5,160 patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for localized breast cancer at 11 different centers. They found that residual cancer burden (RCB) was significantly associated with event-free (EFS) and distant recurrence-free survival. The value of calculating RCB was seen across all breast cancer tumor phenotypes (SABCS 2019, Abstract GS5-01).

RCB is calculated by analyzing the residual disease after NAC for the primary tumor bed, the number of positive axillary nodes, and the size of largest node metastasis. It is graded from RCB-0 (pCR) to RCB-III (extensive residual disease).

Both EFS and distant recurrence-free survival were strongly associated with RCB for the overall population and for each breast cancer subtype. For hormone receptor–positive/HER2-negative disease there was a slight hiccup in that RCB-0 was associated with a 10-year EFS of 81%, but EFS was 86% for RCB-I. Fortunately, the prognostic reliability of RCB was clear for RCB-II (69%) and RCB-III (52%). The presenter, W. Fraser Symmans, MD, commented that RCB is most prognostic when higher levels of residual disease are present. RCB remained prognostic in multivariate models adjusting for age, grade, and clinical T and N stage at diagnosis.

How these results influence practice

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with localized breast cancer, we struggle when patients ask: “So, doctor, how am I likely to do?” We piece together a complicated – and inconsistent – answer, based on breast cancer subtype, original stage of disease, whether pCR was attained, and other factors.

For patients with triple-negative breast cancer, we have the option of adding capecitabine and/or participation in ongoing clinical trials, for patients with residual disease after NAC. Among the HER2-positive patients, we have data from the KATHERINE, ExtaNET, and APHINITY trials that provide options for additional treatment in those patients, as well. For patients with potentially hormonally responsive, HER2-negative disease, we can emphasize the importance of postoperative adjuvant endocrine therapy, the mandate for continued adherence to oral therapy, and the lower likelihood of (and prognostic value of) pCR in that breast cancer subtype.

Where we previously had a complicated, nuanced discussion, we now have data from a multi-institutional, meticulous analysis to guide further treatment, candidacy for clinical trials, and our expectations of what would be meaningful results from additional therapy. This meets my definition of “practice-changing” research.

APHINITY follow-up

APHINITY was a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that previously demonstrated that pertuzumab added to standard chemotherapy plus 1 year of trastuzumab in operable HER2-positive breast cancer was associated with modest, but statistically significant, improvement in invasive disease–free survival (IDFS), compared with placebo and chemotherapy plus trastuzumab (hazard ratio, 0.81; P = .04). When the initial results – with a median follow-up of 45.4 months – were published, the authors promised an update at 6 years. Martine Piccart, MD, PhD, provided that update at the 2019 SABCS (Abstract GS1-04).

In the updated analysis, overall survival was 94.8% among patients on the pertuzumab arm and 93.9% among patients taking placebo (HR, 0.85). IDFS rates were 90.6% versus 87.8% in the intent-to-treat population. The investigator commented that this difference was caused mainly by a reduction in distant and loco-regional recurrences.

Central nervous system metastases, contralateral invasive breast cancers, and death without a prior event were no different between the two treatment groups.

Improvement in IDFS (the primary endpoint) from pertuzumab was most impressive in the node-positive cohort, 87.9% versus 83.4% for placebo (HR, 0.72). There was no benefit in the node-negative population (95.0% vs. 94.9%; HR, 1.02).

In contrast to the 3-year analysis, the benefits in IDFS were seen regardless of hormone receptor status. Additionally, no new safety concerns emerged. The rate of severe cardiac events was below 1% in both groups.

How these results influence practice

“Patience is a virtue” appeared for the first time in the English language around 1360, in William Langland’s poem “Piers Plowman.” They are true words, indeed.

When the initial results of APHINITY were published in 2017, they led to the approval of pertuzumab as an addition to chemotherapy plus trastuzumab for high-risk, early, HER2-positive breast cancer patients. Still, the difference in IDFS curves was visually unimpressive (absolute difference 1.7% in the intent-to-treat and 3.2% in the node-positive patients) and pertuzumab was associated with more grade 3 toxicities (primarily diarrhea) and treatment discontinuations.

An optimist would have observed that the IDFS curves in 2017 did not start to diverge until 24 months and would have noted that the divergence increased with time. That virtuously patient person would have expected that the second interim analysis would show larger absolute benefits, and that the hormone receptor–positive patients (64% of the total) would not yet have relapsed by the first interim analysis and that pertuzumab’s benefit in that group would emerge late.

That appears to be what is happening. It provides hope that an overall survival benefit will become more evident with time. If the target P value for an overall survival difference (.0012) is met by the time of the third interim analysis, our patience (and the FDA’s decision to grant approval for pertuzumab for this indication) will have been amply rewarded. For selected HER2-posiitve patients with high RCB, especially those who tolerated neoadjuvant trastuzumab plus pertuzumab regimens, postoperative adjuvant pertuzumab may be an appealing option.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I Will Treat My Next Patient,” I highlight two presentations from the recent San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) that will likely change practice for some breast cancer patients – even before the ball drops in Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

Residual cancer burden

Researchers reported a multi-institutional analysis of individual patient-level data on 5,160 patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for localized breast cancer at 11 different centers. They found that residual cancer burden (RCB) was significantly associated with event-free (EFS) and distant recurrence-free survival. The value of calculating RCB was seen across all breast cancer tumor phenotypes (SABCS 2019, Abstract GS5-01).

RCB is calculated by analyzing the residual disease after NAC for the primary tumor bed, the number of positive axillary nodes, and the size of largest node metastasis. It is graded from RCB-0 (pCR) to RCB-III (extensive residual disease).

Both EFS and distant recurrence-free survival were strongly associated with RCB for the overall population and for each breast cancer subtype. For hormone receptor–positive/HER2-negative disease there was a slight hiccup in that RCB-0 was associated with a 10-year EFS of 81%, but EFS was 86% for RCB-I. Fortunately, the prognostic reliability of RCB was clear for RCB-II (69%) and RCB-III (52%). The presenter, W. Fraser Symmans, MD, commented that RCB is most prognostic when higher levels of residual disease are present. RCB remained prognostic in multivariate models adjusting for age, grade, and clinical T and N stage at diagnosis.

How these results influence practice

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with localized breast cancer, we struggle when patients ask: “So, doctor, how am I likely to do?” We piece together a complicated – and inconsistent – answer, based on breast cancer subtype, original stage of disease, whether pCR was attained, and other factors.

For patients with triple-negative breast cancer, we have the option of adding capecitabine and/or participation in ongoing clinical trials, for patients with residual disease after NAC. Among the HER2-positive patients, we have data from the KATHERINE, ExtaNET, and APHINITY trials that provide options for additional treatment in those patients, as well. For patients with potentially hormonally responsive, HER2-negative disease, we can emphasize the importance of postoperative adjuvant endocrine therapy, the mandate for continued adherence to oral therapy, and the lower likelihood of (and prognostic value of) pCR in that breast cancer subtype.

Where we previously had a complicated, nuanced discussion, we now have data from a multi-institutional, meticulous analysis to guide further treatment, candidacy for clinical trials, and our expectations of what would be meaningful results from additional therapy. This meets my definition of “practice-changing” research.

APHINITY follow-up

APHINITY was a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that previously demonstrated that pertuzumab added to standard chemotherapy plus 1 year of trastuzumab in operable HER2-positive breast cancer was associated with modest, but statistically significant, improvement in invasive disease–free survival (IDFS), compared with placebo and chemotherapy plus trastuzumab (hazard ratio, 0.81; P = .04). When the initial results – with a median follow-up of 45.4 months – were published, the authors promised an update at 6 years. Martine Piccart, MD, PhD, provided that update at the 2019 SABCS (Abstract GS1-04).

In the updated analysis, overall survival was 94.8% among patients on the pertuzumab arm and 93.9% among patients taking placebo (HR, 0.85). IDFS rates were 90.6% versus 87.8% in the intent-to-treat population. The investigator commented that this difference was caused mainly by a reduction in distant and loco-regional recurrences.

Central nervous system metastases, contralateral invasive breast cancers, and death without a prior event were no different between the two treatment groups.

Improvement in IDFS (the primary endpoint) from pertuzumab was most impressive in the node-positive cohort, 87.9% versus 83.4% for placebo (HR, 0.72). There was no benefit in the node-negative population (95.0% vs. 94.9%; HR, 1.02).

In contrast to the 3-year analysis, the benefits in IDFS were seen regardless of hormone receptor status. Additionally, no new safety concerns emerged. The rate of severe cardiac events was below 1% in both groups.

How these results influence practice

“Patience is a virtue” appeared for the first time in the English language around 1360, in William Langland’s poem “Piers Plowman.” They are true words, indeed.

When the initial results of APHINITY were published in 2017, they led to the approval of pertuzumab as an addition to chemotherapy plus trastuzumab for high-risk, early, HER2-positive breast cancer patients. Still, the difference in IDFS curves was visually unimpressive (absolute difference 1.7% in the intent-to-treat and 3.2% in the node-positive patients) and pertuzumab was associated with more grade 3 toxicities (primarily diarrhea) and treatment discontinuations.

An optimist would have observed that the IDFS curves in 2017 did not start to diverge until 24 months and would have noted that the divergence increased with time. That virtuously patient person would have expected that the second interim analysis would show larger absolute benefits, and that the hormone receptor–positive patients (64% of the total) would not yet have relapsed by the first interim analysis and that pertuzumab’s benefit in that group would emerge late.

That appears to be what is happening. It provides hope that an overall survival benefit will become more evident with time. If the target P value for an overall survival difference (.0012) is met by the time of the third interim analysis, our patience (and the FDA’s decision to grant approval for pertuzumab for this indication) will have been amply rewarded. For selected HER2-posiitve patients with high RCB, especially those who tolerated neoadjuvant trastuzumab plus pertuzumab regimens, postoperative adjuvant pertuzumab may be an appealing option.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I Will Treat My Next Patient,” I highlight two presentations from the recent San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) that will likely change practice for some breast cancer patients – even before the ball drops in Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

Residual cancer burden

Researchers reported a multi-institutional analysis of individual patient-level data on 5,160 patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for localized breast cancer at 11 different centers. They found that residual cancer burden (RCB) was significantly associated with event-free (EFS) and distant recurrence-free survival. The value of calculating RCB was seen across all breast cancer tumor phenotypes (SABCS 2019, Abstract GS5-01).

RCB is calculated by analyzing the residual disease after NAC for the primary tumor bed, the number of positive axillary nodes, and the size of largest node metastasis. It is graded from RCB-0 (pCR) to RCB-III (extensive residual disease).

Both EFS and distant recurrence-free survival were strongly associated with RCB for the overall population and for each breast cancer subtype. For hormone receptor–positive/HER2-negative disease there was a slight hiccup in that RCB-0 was associated with a 10-year EFS of 81%, but EFS was 86% for RCB-I. Fortunately, the prognostic reliability of RCB was clear for RCB-II (69%) and RCB-III (52%). The presenter, W. Fraser Symmans, MD, commented that RCB is most prognostic when higher levels of residual disease are present. RCB remained prognostic in multivariate models adjusting for age, grade, and clinical T and N stage at diagnosis.

How these results influence practice

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with localized breast cancer, we struggle when patients ask: “So, doctor, how am I likely to do?” We piece together a complicated – and inconsistent – answer, based on breast cancer subtype, original stage of disease, whether pCR was attained, and other factors.

For patients with triple-negative breast cancer, we have the option of adding capecitabine and/or participation in ongoing clinical trials, for patients with residual disease after NAC. Among the HER2-positive patients, we have data from the KATHERINE, ExtaNET, and APHINITY trials that provide options for additional treatment in those patients, as well. For patients with potentially hormonally responsive, HER2-negative disease, we can emphasize the importance of postoperative adjuvant endocrine therapy, the mandate for continued adherence to oral therapy, and the lower likelihood of (and prognostic value of) pCR in that breast cancer subtype.

Where we previously had a complicated, nuanced discussion, we now have data from a multi-institutional, meticulous analysis to guide further treatment, candidacy for clinical trials, and our expectations of what would be meaningful results from additional therapy. This meets my definition of “practice-changing” research.

APHINITY follow-up