User login

The Great Pretender

Susannah Cahalan’s new book challenges an experiment that changed psychiatry

As an undergraduate psychology major, I was taught about the Rosenhan study in several of my courses. My professors lectured about the shocking findings psychologist David Rosenhan, PhD, documented in a 1973 Science article, “On Being Sane in Insane Places” and these findings lent themselves to lecture hall drama. Eight people presented to hospitals and said they heard voices saying: “empty, hollow, thud.” These “pseudopatients” exhibited no other psychiatric symptoms but were admitted, diagnosed with schizophrenia, and observations of their behavior were made. The charts included notes such as, “Patient exhibits writing behavior,” my professors said. The pseudopatients were kept for an average of 19 days, and one for as long as 51 days. The decades have passed, and there are many things I learned in college that I have since forgotten, but I remember “empty, hollow, thud,” and the famous Rosenhan experiment.

I was eager to read Susannah Cahalan’s book, “The Great Pretender” (Grand Central Publishing, 2019), which puts both Dr. Rosenhan and his pseudopatient study under a microscope. Ms. Cahalan is the author of the page-turner, Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness (Free Press, 2012), where she recounted her own struggle with a psychotic episode. Ms. Cahalan, a young reporter in New York City, became psychotic and then catatonic; her condition perplexed the neurologists who were treating her on an inpatient unit, and they were on the verge of transferring her to psychiatry when a diagnosis of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis was suspected and then confirmed with a brain biopsy. Ms. Cahalan made a full recovery after treatment with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis. While Ms. Cahalan’s symptoms were classic for a severe psychotic disorder, there was reason to believe that this was not a primary psychiatric disorder: She was having grand mal seizures. Her book was a bestseller, and she has spoken widely to make others aware of this rare illness that masquerades as psychosis. I heard her speak at the opening session of the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in May of 2017.“My family, like many families before them, fought against the tyranny of the mental illness label,” Ms. Cahalan writes at the very beginning of “The Great Pretender.” She goes on to talk about how psychiatry differs from other medical fields: It’s the only specialty where people can be treated against their will; psychiatry casts judgments on the person; mental illness is poorly defined – perhaps there is no clear divide between normal and mad; and psychiatric disorders are less “real” than other illnesses. Throughout the book she refers to psychiatrists as smug and arrogant.

Ms. Cahalan takes on the task of documenting the horrors of psychiatry’s often sordid history, starting with journalist Nellie Bly’s 1887 journey into to a psychiatric facility to expose the abuses there. Certainly, psychiatry’s history is sordid. Ms. Cahalan talks about inhumane conditions in overcrowded psychiatric hospitals, about our sad chapter of lobotomies, about the influence of psychoanalysis on diagnosis and treatment, and about how homosexuality was once an illness and now is not. She includes “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “The Myth of Mental Illness,” big pharma, and the Goldwater fiasco. In her recounting of the history, it’s all bad. She mentions Benjamin Rush, MD, only once, as the creator of “ ‘... the tranquilizing chair’ (a case of the worst false advertising ever), a terrifying sensory-deprivation apparatus in which patients were strapped down to a chair with a wooden box placed over their heads to block stimulation, restrict movement, and reduce blood to the brain.” Dr. Rush’s role as the father of American psychiatry who challenged the belief that mental illness was the result of demonic possession, gets no mention. Nor does Ms. Cahalan note that he founded Pennsylvania Hospital, where moral and occupational therapy revolutionized the treatment of those with mental illness.

So there’s her story, her rendition of the history of American psychiatry, and through this she weaves in the story of the Rosenhan experiment.

“ ‘It all started out as a dare,’ Dr. Rosenhan told a local newspaper, ‘I was teaching psychology at Swarthmore, and my students were saying that the course was too conceptual and abstract. So I said, ‘Okay, if you really want to know what mental patients are like, become mental patients.’ ”

Really? I read this and wondered how a psychologist could talk about people who had been hospitalized with psychiatric disorders as though they were aliens. Certainly, some of these students, their family members, or their friends must have been hospitalized at some point. Yet all through, there is this sense that the patients are other, and the discovery of the undercover operation is that the patients are actually human beings! Dr. Rosenhan, who was one of the pseudopatients, goes on to conclude that the label is everything, that once labeled they are treated differently by the nurses in “cages” and the doctors who walk by and avert their gaze. A second man Ms. Cahalan named, also one of the pseudopatients, had a similar experience. A third subject she located was not included in the study: His experience was counter to the findings of the study, his time in the hospital was a positive, he found it comforting, and the experiences he had there had a lasting positive influence on his life.

Ms. Cahalan talks about the publication of “On Being Sane in Insane Places” as a study that was finally scientific, one that changed all of psychiatry, and was the driving force for the creation of the DSM-III and the closure of state hospitals. I wondered if it was as influential as Ms. Cahalan claims, and I asked some psychiatrists who were practicing in 1973 when the article was published. I wanted to know if this study rocked their world.

“At first, with the great amount of publicity the study generated, it was added fodder for the antipsychiatrists, including the Scientologists and Szaszians,” Steven Sharfstein, MD, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, told me. “But as young psychiatrists in the trenches, business continued to boom, and we continued to do the best job we could with diagnosis, assessment of risk, involuntary commitment, and treatment. And from what I recall, morale was high in the 1970s. We had some new medications and psychotherapies, and there was community activism. Faking symptoms to gain admission seemed to be a no-brainer, but keeping people for long stays was more problematic.”

E. Fuller Torrey, MD, the founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center who worked for many years treating patients at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, replied: “It is important to remember that this study was published at the height of the deinstitutionalization movement and quite likely accelerated it. As I recall, at the time it seemed odd that all eight patients claimed to have had similar experiences while hospitalized. I think the main effect of the study was to provide ammunition for the antipsychiatrists.”

Ms. Cahalan has bought into the antipsychiatry movement full force. It’s not until the very end that there is any acknowledgment that psychiatry ever helped anyone, and even then, it’s a bit begrudging. Worse, she neglects to mention that people with psychiatric disorders suffer because of their psychic pain; one could get through this book and believe that people with mental illness struggle only because they are labeled and then mistreated, and for someone who has suffered herself, she misses the essence of how awful it is to be ill, and that people are often helped by psychiatric treatments. When she finally adds a paragraph talking about the usefulness of psychotropics, it’s with a caveat. “But I’m not here to rail against the drugs. There are plenty of places you can get that perspective. I see that these drugs help many people lead full and meaningful lives. It would be folly to discount their worth. We also can’t deny that the situation is complicated.”

There are moments in the manuscript where I found it difficult to know what were Dr. Rosenhan’s interpretations and what were Ms. Callahan’s interpretations of Dr. Rosenhan’s experiences. A lot of assumptions are made – particularly about the motivations of the hospital staff – and I wasn’t always sure they were correct. For example, on his second day in the hospital, Dr. Rosenhan asked a nurse for the newspaper. When she tells him it hasn’t come yet, he concludes that the staff is keeping the newspapers from the patients. And when a staff member is initially chatty then later shuns Dr. Rosenhan, he concludes that the man initially mistook him for a psychiatrist because he looks professorial. Both Ms. Cahalan and Dr. Rosenhan approach psychiatry with biases, and they don’t always question their assumptions.

, a professor who didn’t treat patients. This intermixing of the two fields felt contrived to me, and gave too much credence to the idea that no one really knows sane from disordered, and everyone was embracing the antipsychiatry dogma. Surely, someone during the those years must have liked their psychiatrist.

That said, Ms. Cahalan does a phenomenal job of infiltrating the world of the late Dr. Rosenhan. She starts out enamored by him and by his finding that psychiatrists can’t tell real illness from faked disorder. She meets with his friends, his son, his colleagues, his students, and she flies all over the country to meet with those who can help her understand him. She gains access to his personal files and to the book he started to write about the experiment, then abandoned, which eventually resulted in a lawsuit by Doubleday to have the book’s advance returned. At one point, she even hires a private detective.

What is Ms. Cahalan looking for so desperately? She’s looking for these anonymous pseudopatients, the people who were admitted to these unnamed state hospitals, who made observations and took notes, who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and then finally released. She’s looking for the truth, and while she identifies Dr. Rosenhan and two other pseudopatients as people who faked their way into the hospital, she finds a mass of contradictions. The one pseudopatient was excluded from the study – he is the one who felt comforted by his time in the hospital. The other six pseudopatients could not be found, despite Ms. Cahalan’s heroic attempts. Furthermore, she found many inconsistencies in what Dr. Rosenhan reported, and his hospital notes revealed more than a presentation for voices saying “empty, hollow, thud.” He reported it had been going on for months, that he had put copper over his ears to block the sound, and that he felt suicidal.

Ultimately, Ms. Cahalan was left to conclude that the Rosenhan experiment was a lie, that the pseudopatients likely never existed and the article was a fabrication. She brings up other studies that have been proven to be fraudulent, and by this point, our faith in all of science is pretty shaken.

Ms. Cahalan took a long journey to get us to this place, one that spent a lot of effort in bashing psychiatry, finally concluding that, as a result of this fraudulent experiment, too many hospitals have been shuttered – leaving our sickest patients to the streets and to the jails – and that there are not enough mental health professionals. As a psychiatrist – one who is often willing to question our practices – I was distracted by the flagrant antipsychiatry sentiments. Reading past that, Ms. Cahalan’s remarkable detective work and creative intermingling of the Rosenhan experiment layered on the history of psychiatry, further layered on her own experience with psychosis, makes for an amazing story. The Rosenhan study may have rocked the world of psychiatry; the fact that it was fabricated should rock us even more.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Susannah Cahalan’s new book challenges an experiment that changed psychiatry

Susannah Cahalan’s new book challenges an experiment that changed psychiatry

As an undergraduate psychology major, I was taught about the Rosenhan study in several of my courses. My professors lectured about the shocking findings psychologist David Rosenhan, PhD, documented in a 1973 Science article, “On Being Sane in Insane Places” and these findings lent themselves to lecture hall drama. Eight people presented to hospitals and said they heard voices saying: “empty, hollow, thud.” These “pseudopatients” exhibited no other psychiatric symptoms but were admitted, diagnosed with schizophrenia, and observations of their behavior were made. The charts included notes such as, “Patient exhibits writing behavior,” my professors said. The pseudopatients were kept for an average of 19 days, and one for as long as 51 days. The decades have passed, and there are many things I learned in college that I have since forgotten, but I remember “empty, hollow, thud,” and the famous Rosenhan experiment.

I was eager to read Susannah Cahalan’s book, “The Great Pretender” (Grand Central Publishing, 2019), which puts both Dr. Rosenhan and his pseudopatient study under a microscope. Ms. Cahalan is the author of the page-turner, Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness (Free Press, 2012), where she recounted her own struggle with a psychotic episode. Ms. Cahalan, a young reporter in New York City, became psychotic and then catatonic; her condition perplexed the neurologists who were treating her on an inpatient unit, and they were on the verge of transferring her to psychiatry when a diagnosis of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis was suspected and then confirmed with a brain biopsy. Ms. Cahalan made a full recovery after treatment with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis. While Ms. Cahalan’s symptoms were classic for a severe psychotic disorder, there was reason to believe that this was not a primary psychiatric disorder: She was having grand mal seizures. Her book was a bestseller, and she has spoken widely to make others aware of this rare illness that masquerades as psychosis. I heard her speak at the opening session of the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in May of 2017.“My family, like many families before them, fought against the tyranny of the mental illness label,” Ms. Cahalan writes at the very beginning of “The Great Pretender.” She goes on to talk about how psychiatry differs from other medical fields: It’s the only specialty where people can be treated against their will; psychiatry casts judgments on the person; mental illness is poorly defined – perhaps there is no clear divide between normal and mad; and psychiatric disorders are less “real” than other illnesses. Throughout the book she refers to psychiatrists as smug and arrogant.

Ms. Cahalan takes on the task of documenting the horrors of psychiatry’s often sordid history, starting with journalist Nellie Bly’s 1887 journey into to a psychiatric facility to expose the abuses there. Certainly, psychiatry’s history is sordid. Ms. Cahalan talks about inhumane conditions in overcrowded psychiatric hospitals, about our sad chapter of lobotomies, about the influence of psychoanalysis on diagnosis and treatment, and about how homosexuality was once an illness and now is not. She includes “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “The Myth of Mental Illness,” big pharma, and the Goldwater fiasco. In her recounting of the history, it’s all bad. She mentions Benjamin Rush, MD, only once, as the creator of “ ‘... the tranquilizing chair’ (a case of the worst false advertising ever), a terrifying sensory-deprivation apparatus in which patients were strapped down to a chair with a wooden box placed over their heads to block stimulation, restrict movement, and reduce blood to the brain.” Dr. Rush’s role as the father of American psychiatry who challenged the belief that mental illness was the result of demonic possession, gets no mention. Nor does Ms. Cahalan note that he founded Pennsylvania Hospital, where moral and occupational therapy revolutionized the treatment of those with mental illness.

So there’s her story, her rendition of the history of American psychiatry, and through this she weaves in the story of the Rosenhan experiment.

“ ‘It all started out as a dare,’ Dr. Rosenhan told a local newspaper, ‘I was teaching psychology at Swarthmore, and my students were saying that the course was too conceptual and abstract. So I said, ‘Okay, if you really want to know what mental patients are like, become mental patients.’ ”

Really? I read this and wondered how a psychologist could talk about people who had been hospitalized with psychiatric disorders as though they were aliens. Certainly, some of these students, their family members, or their friends must have been hospitalized at some point. Yet all through, there is this sense that the patients are other, and the discovery of the undercover operation is that the patients are actually human beings! Dr. Rosenhan, who was one of the pseudopatients, goes on to conclude that the label is everything, that once labeled they are treated differently by the nurses in “cages” and the doctors who walk by and avert their gaze. A second man Ms. Cahalan named, also one of the pseudopatients, had a similar experience. A third subject she located was not included in the study: His experience was counter to the findings of the study, his time in the hospital was a positive, he found it comforting, and the experiences he had there had a lasting positive influence on his life.

Ms. Cahalan talks about the publication of “On Being Sane in Insane Places” as a study that was finally scientific, one that changed all of psychiatry, and was the driving force for the creation of the DSM-III and the closure of state hospitals. I wondered if it was as influential as Ms. Cahalan claims, and I asked some psychiatrists who were practicing in 1973 when the article was published. I wanted to know if this study rocked their world.

“At first, with the great amount of publicity the study generated, it was added fodder for the antipsychiatrists, including the Scientologists and Szaszians,” Steven Sharfstein, MD, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, told me. “But as young psychiatrists in the trenches, business continued to boom, and we continued to do the best job we could with diagnosis, assessment of risk, involuntary commitment, and treatment. And from what I recall, morale was high in the 1970s. We had some new medications and psychotherapies, and there was community activism. Faking symptoms to gain admission seemed to be a no-brainer, but keeping people for long stays was more problematic.”

E. Fuller Torrey, MD, the founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center who worked for many years treating patients at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, replied: “It is important to remember that this study was published at the height of the deinstitutionalization movement and quite likely accelerated it. As I recall, at the time it seemed odd that all eight patients claimed to have had similar experiences while hospitalized. I think the main effect of the study was to provide ammunition for the antipsychiatrists.”

Ms. Cahalan has bought into the antipsychiatry movement full force. It’s not until the very end that there is any acknowledgment that psychiatry ever helped anyone, and even then, it’s a bit begrudging. Worse, she neglects to mention that people with psychiatric disorders suffer because of their psychic pain; one could get through this book and believe that people with mental illness struggle only because they are labeled and then mistreated, and for someone who has suffered herself, she misses the essence of how awful it is to be ill, and that people are often helped by psychiatric treatments. When she finally adds a paragraph talking about the usefulness of psychotropics, it’s with a caveat. “But I’m not here to rail against the drugs. There are plenty of places you can get that perspective. I see that these drugs help many people lead full and meaningful lives. It would be folly to discount their worth. We also can’t deny that the situation is complicated.”

There are moments in the manuscript where I found it difficult to know what were Dr. Rosenhan’s interpretations and what were Ms. Callahan’s interpretations of Dr. Rosenhan’s experiences. A lot of assumptions are made – particularly about the motivations of the hospital staff – and I wasn’t always sure they were correct. For example, on his second day in the hospital, Dr. Rosenhan asked a nurse for the newspaper. When she tells him it hasn’t come yet, he concludes that the staff is keeping the newspapers from the patients. And when a staff member is initially chatty then later shuns Dr. Rosenhan, he concludes that the man initially mistook him for a psychiatrist because he looks professorial. Both Ms. Cahalan and Dr. Rosenhan approach psychiatry with biases, and they don’t always question their assumptions.

, a professor who didn’t treat patients. This intermixing of the two fields felt contrived to me, and gave too much credence to the idea that no one really knows sane from disordered, and everyone was embracing the antipsychiatry dogma. Surely, someone during the those years must have liked their psychiatrist.

That said, Ms. Cahalan does a phenomenal job of infiltrating the world of the late Dr. Rosenhan. She starts out enamored by him and by his finding that psychiatrists can’t tell real illness from faked disorder. She meets with his friends, his son, his colleagues, his students, and she flies all over the country to meet with those who can help her understand him. She gains access to his personal files and to the book he started to write about the experiment, then abandoned, which eventually resulted in a lawsuit by Doubleday to have the book’s advance returned. At one point, she even hires a private detective.

What is Ms. Cahalan looking for so desperately? She’s looking for these anonymous pseudopatients, the people who were admitted to these unnamed state hospitals, who made observations and took notes, who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and then finally released. She’s looking for the truth, and while she identifies Dr. Rosenhan and two other pseudopatients as people who faked their way into the hospital, she finds a mass of contradictions. The one pseudopatient was excluded from the study – he is the one who felt comforted by his time in the hospital. The other six pseudopatients could not be found, despite Ms. Cahalan’s heroic attempts. Furthermore, she found many inconsistencies in what Dr. Rosenhan reported, and his hospital notes revealed more than a presentation for voices saying “empty, hollow, thud.” He reported it had been going on for months, that he had put copper over his ears to block the sound, and that he felt suicidal.

Ultimately, Ms. Cahalan was left to conclude that the Rosenhan experiment was a lie, that the pseudopatients likely never existed and the article was a fabrication. She brings up other studies that have been proven to be fraudulent, and by this point, our faith in all of science is pretty shaken.

Ms. Cahalan took a long journey to get us to this place, one that spent a lot of effort in bashing psychiatry, finally concluding that, as a result of this fraudulent experiment, too many hospitals have been shuttered – leaving our sickest patients to the streets and to the jails – and that there are not enough mental health professionals. As a psychiatrist – one who is often willing to question our practices – I was distracted by the flagrant antipsychiatry sentiments. Reading past that, Ms. Cahalan’s remarkable detective work and creative intermingling of the Rosenhan experiment layered on the history of psychiatry, further layered on her own experience with psychosis, makes for an amazing story. The Rosenhan study may have rocked the world of psychiatry; the fact that it was fabricated should rock us even more.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

As an undergraduate psychology major, I was taught about the Rosenhan study in several of my courses. My professors lectured about the shocking findings psychologist David Rosenhan, PhD, documented in a 1973 Science article, “On Being Sane in Insane Places” and these findings lent themselves to lecture hall drama. Eight people presented to hospitals and said they heard voices saying: “empty, hollow, thud.” These “pseudopatients” exhibited no other psychiatric symptoms but were admitted, diagnosed with schizophrenia, and observations of their behavior were made. The charts included notes such as, “Patient exhibits writing behavior,” my professors said. The pseudopatients were kept for an average of 19 days, and one for as long as 51 days. The decades have passed, and there are many things I learned in college that I have since forgotten, but I remember “empty, hollow, thud,” and the famous Rosenhan experiment.

I was eager to read Susannah Cahalan’s book, “The Great Pretender” (Grand Central Publishing, 2019), which puts both Dr. Rosenhan and his pseudopatient study under a microscope. Ms. Cahalan is the author of the page-turner, Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness (Free Press, 2012), where she recounted her own struggle with a psychotic episode. Ms. Cahalan, a young reporter in New York City, became psychotic and then catatonic; her condition perplexed the neurologists who were treating her on an inpatient unit, and they were on the verge of transferring her to psychiatry when a diagnosis of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis was suspected and then confirmed with a brain biopsy. Ms. Cahalan made a full recovery after treatment with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis. While Ms. Cahalan’s symptoms were classic for a severe psychotic disorder, there was reason to believe that this was not a primary psychiatric disorder: She was having grand mal seizures. Her book was a bestseller, and she has spoken widely to make others aware of this rare illness that masquerades as psychosis. I heard her speak at the opening session of the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in May of 2017.“My family, like many families before them, fought against the tyranny of the mental illness label,” Ms. Cahalan writes at the very beginning of “The Great Pretender.” She goes on to talk about how psychiatry differs from other medical fields: It’s the only specialty where people can be treated against their will; psychiatry casts judgments on the person; mental illness is poorly defined – perhaps there is no clear divide between normal and mad; and psychiatric disorders are less “real” than other illnesses. Throughout the book she refers to psychiatrists as smug and arrogant.

Ms. Cahalan takes on the task of documenting the horrors of psychiatry’s often sordid history, starting with journalist Nellie Bly’s 1887 journey into to a psychiatric facility to expose the abuses there. Certainly, psychiatry’s history is sordid. Ms. Cahalan talks about inhumane conditions in overcrowded psychiatric hospitals, about our sad chapter of lobotomies, about the influence of psychoanalysis on diagnosis and treatment, and about how homosexuality was once an illness and now is not. She includes “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “The Myth of Mental Illness,” big pharma, and the Goldwater fiasco. In her recounting of the history, it’s all bad. She mentions Benjamin Rush, MD, only once, as the creator of “ ‘... the tranquilizing chair’ (a case of the worst false advertising ever), a terrifying sensory-deprivation apparatus in which patients were strapped down to a chair with a wooden box placed over their heads to block stimulation, restrict movement, and reduce blood to the brain.” Dr. Rush’s role as the father of American psychiatry who challenged the belief that mental illness was the result of demonic possession, gets no mention. Nor does Ms. Cahalan note that he founded Pennsylvania Hospital, where moral and occupational therapy revolutionized the treatment of those with mental illness.

So there’s her story, her rendition of the history of American psychiatry, and through this she weaves in the story of the Rosenhan experiment.

“ ‘It all started out as a dare,’ Dr. Rosenhan told a local newspaper, ‘I was teaching psychology at Swarthmore, and my students were saying that the course was too conceptual and abstract. So I said, ‘Okay, if you really want to know what mental patients are like, become mental patients.’ ”

Really? I read this and wondered how a psychologist could talk about people who had been hospitalized with psychiatric disorders as though they were aliens. Certainly, some of these students, their family members, or their friends must have been hospitalized at some point. Yet all through, there is this sense that the patients are other, and the discovery of the undercover operation is that the patients are actually human beings! Dr. Rosenhan, who was one of the pseudopatients, goes on to conclude that the label is everything, that once labeled they are treated differently by the nurses in “cages” and the doctors who walk by and avert their gaze. A second man Ms. Cahalan named, also one of the pseudopatients, had a similar experience. A third subject she located was not included in the study: His experience was counter to the findings of the study, his time in the hospital was a positive, he found it comforting, and the experiences he had there had a lasting positive influence on his life.

Ms. Cahalan talks about the publication of “On Being Sane in Insane Places” as a study that was finally scientific, one that changed all of psychiatry, and was the driving force for the creation of the DSM-III and the closure of state hospitals. I wondered if it was as influential as Ms. Cahalan claims, and I asked some psychiatrists who were practicing in 1973 when the article was published. I wanted to know if this study rocked their world.

“At first, with the great amount of publicity the study generated, it was added fodder for the antipsychiatrists, including the Scientologists and Szaszians,” Steven Sharfstein, MD, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, told me. “But as young psychiatrists in the trenches, business continued to boom, and we continued to do the best job we could with diagnosis, assessment of risk, involuntary commitment, and treatment. And from what I recall, morale was high in the 1970s. We had some new medications and psychotherapies, and there was community activism. Faking symptoms to gain admission seemed to be a no-brainer, but keeping people for long stays was more problematic.”

E. Fuller Torrey, MD, the founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center who worked for many years treating patients at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, replied: “It is important to remember that this study was published at the height of the deinstitutionalization movement and quite likely accelerated it. As I recall, at the time it seemed odd that all eight patients claimed to have had similar experiences while hospitalized. I think the main effect of the study was to provide ammunition for the antipsychiatrists.”

Ms. Cahalan has bought into the antipsychiatry movement full force. It’s not until the very end that there is any acknowledgment that psychiatry ever helped anyone, and even then, it’s a bit begrudging. Worse, she neglects to mention that people with psychiatric disorders suffer because of their psychic pain; one could get through this book and believe that people with mental illness struggle only because they are labeled and then mistreated, and for someone who has suffered herself, she misses the essence of how awful it is to be ill, and that people are often helped by psychiatric treatments. When she finally adds a paragraph talking about the usefulness of psychotropics, it’s with a caveat. “But I’m not here to rail against the drugs. There are plenty of places you can get that perspective. I see that these drugs help many people lead full and meaningful lives. It would be folly to discount their worth. We also can’t deny that the situation is complicated.”

There are moments in the manuscript where I found it difficult to know what were Dr. Rosenhan’s interpretations and what were Ms. Callahan’s interpretations of Dr. Rosenhan’s experiences. A lot of assumptions are made – particularly about the motivations of the hospital staff – and I wasn’t always sure they were correct. For example, on his second day in the hospital, Dr. Rosenhan asked a nurse for the newspaper. When she tells him it hasn’t come yet, he concludes that the staff is keeping the newspapers from the patients. And when a staff member is initially chatty then later shuns Dr. Rosenhan, he concludes that the man initially mistook him for a psychiatrist because he looks professorial. Both Ms. Cahalan and Dr. Rosenhan approach psychiatry with biases, and they don’t always question their assumptions.

, a professor who didn’t treat patients. This intermixing of the two fields felt contrived to me, and gave too much credence to the idea that no one really knows sane from disordered, and everyone was embracing the antipsychiatry dogma. Surely, someone during the those years must have liked their psychiatrist.

That said, Ms. Cahalan does a phenomenal job of infiltrating the world of the late Dr. Rosenhan. She starts out enamored by him and by his finding that psychiatrists can’t tell real illness from faked disorder. She meets with his friends, his son, his colleagues, his students, and she flies all over the country to meet with those who can help her understand him. She gains access to his personal files and to the book he started to write about the experiment, then abandoned, which eventually resulted in a lawsuit by Doubleday to have the book’s advance returned. At one point, she even hires a private detective.

What is Ms. Cahalan looking for so desperately? She’s looking for these anonymous pseudopatients, the people who were admitted to these unnamed state hospitals, who made observations and took notes, who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and then finally released. She’s looking for the truth, and while she identifies Dr. Rosenhan and two other pseudopatients as people who faked their way into the hospital, she finds a mass of contradictions. The one pseudopatient was excluded from the study – he is the one who felt comforted by his time in the hospital. The other six pseudopatients could not be found, despite Ms. Cahalan’s heroic attempts. Furthermore, she found many inconsistencies in what Dr. Rosenhan reported, and his hospital notes revealed more than a presentation for voices saying “empty, hollow, thud.” He reported it had been going on for months, that he had put copper over his ears to block the sound, and that he felt suicidal.

Ultimately, Ms. Cahalan was left to conclude that the Rosenhan experiment was a lie, that the pseudopatients likely never existed and the article was a fabrication. She brings up other studies that have been proven to be fraudulent, and by this point, our faith in all of science is pretty shaken.

Ms. Cahalan took a long journey to get us to this place, one that spent a lot of effort in bashing psychiatry, finally concluding that, as a result of this fraudulent experiment, too many hospitals have been shuttered – leaving our sickest patients to the streets and to the jails – and that there are not enough mental health professionals. As a psychiatrist – one who is often willing to question our practices – I was distracted by the flagrant antipsychiatry sentiments. Reading past that, Ms. Cahalan’s remarkable detective work and creative intermingling of the Rosenhan experiment layered on the history of psychiatry, further layered on her own experience with psychosis, makes for an amazing story. The Rosenhan study may have rocked the world of psychiatry; the fact that it was fabricated should rock us even more.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Patients need physicians who see – and feel – beyond the EMR

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

CHICAGO – Speaking to a rapt audience of radiologists, an infectious disease physician who writes and teaches about the importance of human touch in medicine held sway at the opening session of the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

It wasn’t hard for Abraham Verghese, MD, to find points of commonality between those who sit in dark reading rooms and those who roam the wards.

The EMR, Dr. Verghese said, is a “system of epic disaster. It was not designed for ease of use; it was designed for billing. ... Frankly, we are the highest-paid clerical workers in the hospital, and that has to change. The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stone; it ended because we had better ideas.”

The daily EMR click count for physicians has been estimated at 4,000, and it’s but part of the problem, said Dr. Verghese, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “For every hour of cumulative patient care, physicians spend 1½ hours on the computer, and another hour of our personal time at home dealing with our inbox,” he said. EMR systems may dominate clinical life for physicians, “but they were not built for our ease.”

Dr. Verghese is a practicing physician and medical educator, and is also the author of a body of fiction and nonfiction literature that delineates the physician-patient relationship. His TED-style talk followed opening remarks from Valerie Jackson, MD, the president of the Radiological Society of North America, who encouraged radiologists to reach out for a more direct connection with patients and with nonradiologist colleagues.

The patient connection – the human factor that leads many into the practice of medicine – can be eroded for myriad reasons, but health care systems that don’t elevate the physician-patient relationship do so at the peril of serious physician burnout, said Dr. Verghese. By some measures, and in some specialties, half of physicians score high on validated burnout indices – and a burned-out physician is at high risk for leaving the profession.

Dr. Verghese quoted the poet Anatole Broyard, who was treated for prostate cancer and wrote extensively about his experiences.

Wishing for a more personal connection with his physician, Mr. Broyard wrote: “I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps 5 minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh, to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way.”

It’s this opportunity for connection and contemplation that is sacrificed when, as Dr. Verghese said, “the patient in the bed has become a mere icon for the ‘real’ patient in the computer.”

Dr. Jackson, executive director of the American Board of Radiology, and Dr. Verghese both acknowledged that authentic patient connections can make practice more rewarding and reduce the risk of burnout.

Dr. Verghese also discussed other areas of risk when patients and their physicians are separated by an electronic divide.

“We are all getting distracted by our peripheral brains,” and patients may suffer when medical errors result from inattention and a reluctance to “trust what our eyes are showing us,” he said. He and his colleagues solicited and reported 208 vignettes of medical error. In 63% of the cases, the root cause of the error was failure to perform a physical examination (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1322-4.e3). “Patients have a front side – and a back side!” he said, to appreciative laughter. A careful physical exam, he said, involves inspecting – and palpating – both sides.

The act of putting hands on an unclothed patient for a physical exam would violate many societal norms, said Dr. Verghese, were it not for the special rules conferred on the physician-patient relationship.

“One individual in this dyad disrobes and allows touch. In any other context in this society, this is assault,” he said. “The very great privilege of our profession ... is that we are privileged to examine [patients’] bodies, and to touch.”

The gift of this ritual is not to be squandered, he said, adding that patients understand the special rhythm of the physical examination. “If you come in and do a half-assed probe of their belly and stick your stethoscope on top of their paper gown, they are on to you.”

Describing his own method for the physical exam, Dr. Verghese said that there’s something that feels commandeering and intrusive about beginning directly at the head, as one is taught. Instead, he offers an outstretched hand and begins with a handshake, noting grip strength, any tremor, hydration, and condition of skin and nails. Then, he caps the handshake with his other hand and slides two fingers over to the radial pulse, where he gathers more information, all the while strengthening his bond with his patient. His exam, he said, is his own, with its own rhythms and order which have not varied in decades.

Whatever the method, “this skill has to be passed on, and there is no easy way to do it. ... But when you examine well, you are preserving the ‘person-ality,’ the embodied identity of the patient.”

From the time of William Osler – and perhaps before – the physical examination has been a “symbolic centering on the body as a locus of personhood and disease,” said Dr. Verghese.

Dr. Jackson encouraged her radiologist peers to come out from the reading room to greet and connect with patients in the imaging suite. Similarly, Dr. Verghese said, technology can be used to “connect the image, or the biopsy report, or the lab test, to the personhood” of the patient. Bringing a tablet with imaging results or a laboratory readout to the bedside or the exam table and helping the patient place the findings on or within her own body marries the best of old and new.

He shared with the audience his practice for examining patients presenting with chronic fatigue – a condition that can be challenging to diagnose and manage.

These patients “come to you ready for you to join the long line of physicians who have disappointed them,” said Dr. Verghese, who at one time saw many such patients. He said that he developed a strategy of first listening, and then examining. “A very interesting thing happened – the voluble patient began to quiet down” under his examiner’s hands. If patients could, through his approach, relinquish their ceaseless quest for a definitive diagnosis “and instead begin a partnership toward wellness,” he felt he’d reached success. “It was because something magical had transpired in that encounter.”

Neither Dr. Verghese nor Dr. Jackson reported any conflicts of interest relevant to their presentations.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RSNA 2019

Capecitabine extends survival in triple-negative breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment may extend overall survival, according to a meta-analysis involving more than 15,000 patients.

Although a variety of trials have tested capecitabine therapy for early-stage breast cancer, this study is the first to evaluate individual patient data across trials, reported lead author Marion van Mackelenbergh, MD, of University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany, and colleagues.

According to Dr. Mackelenbergh, who presented findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, the two previous literature-based meta-analyses of capecitabine for patients with early-stage breast cancer reported conflicting results; the first study suggested that capecitabine had no benefit as a neoadjuvant therapy, whereas the second study concluded that capecitabine could improve disease-free survival (DFS).

To build upon these findings, the primary objective of the present meta-analysis was to determine how treatment with capecitabine impacts DFS, Dr. Mackelenbergh said. A variety of secondary objectives were also evaluated, including overall survival and a possible interaction between capecitabine-specific toxicities and treatment effects.

The analysis involved 15,457 patients from 12 randomized prospective clinical trials, of whom about half (n = 7,477) were treated in control arms. Slightly more than half (55.9%) of the patients had stage II tumors and about three-fourths (74.0%) presented with nodal involvement. About two-thirds of patients (66.0%) had estrogen receptor–positive disease, about half (56.9%) were progesterone receptor–positive, and 15.1% were human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive. Most of the patients (81.8%) were treated with chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting, whereas the remainder (18.2%) received neoadjuvant therapy.

Cox regression analysis involving all patients in the dataset showed that capecitabine was not associated with a significant improvement in DFS, nor was a significant improvement seen in trials that compared capecitabine against other treatment options. In contrast, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment supported a modest but significant improvement in DFS (hazard ratio, 0.888; P = .0005).

Across all patients, capecitabine was associated with an overall survival advantage, although this benefit was relatively small, with a hazard ratio of 0.892. The overall survival benefit became more pronounced when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment (HR, 0.837).

Of clinical importance, biological subtype analysis showed that only patients with triple-negative breast cancer were deriving survival benefit from capecitabine, particularly when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment. Among patients with triple-negative disease, a 17% overall survival benefit was associated with capecitabine (HR, 0.828). When capecitabine was added to systemic treatment, this survival advantage improved to 22% (HR, 0.778).

No relationship was found between capecitabine-specific toxicity (mucositis, hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea) and patient outcome.

“It can be concluded that the addition of capecitabine to other systemic treatment may be recommended for triple-negative breast cancer patients,” Dr. Mackelenbergh said.

Invited discussant Priyanka Sharma, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City agreed with this conclusion.

“Routine use of capecitabine as a component of neoadjuvant or adjuvant regimens in unselected patients cannot be endorsed,” Dr. Sharma said. “However, capecitabine should be considered in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, especially if response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is utilized as a way to identify eligible patients so as to limit exposure and toxicity to those at the highest risk.”

In terms of the future, Dr. Sharma suggested that research is needed to determine the potential for adjuvant capecitabine among patients with triple-negative breast cancer who have received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy as part of their neoadjuvant regimen. In addition, investigators should evaluate capecitabine efficacy in terms of residual disease and identify relevant predictive biomarkers, Dr. Sharma said.

The investigators reported relationships with Amgen, Lilly, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: van Mackelenbergh M et al. SABCS 2019, Abstract GS1-07.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment may extend overall survival, according to a meta-analysis involving more than 15,000 patients.

Although a variety of trials have tested capecitabine therapy for early-stage breast cancer, this study is the first to evaluate individual patient data across trials, reported lead author Marion van Mackelenbergh, MD, of University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany, and colleagues.

According to Dr. Mackelenbergh, who presented findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, the two previous literature-based meta-analyses of capecitabine for patients with early-stage breast cancer reported conflicting results; the first study suggested that capecitabine had no benefit as a neoadjuvant therapy, whereas the second study concluded that capecitabine could improve disease-free survival (DFS).

To build upon these findings, the primary objective of the present meta-analysis was to determine how treatment with capecitabine impacts DFS, Dr. Mackelenbergh said. A variety of secondary objectives were also evaluated, including overall survival and a possible interaction between capecitabine-specific toxicities and treatment effects.

The analysis involved 15,457 patients from 12 randomized prospective clinical trials, of whom about half (n = 7,477) were treated in control arms. Slightly more than half (55.9%) of the patients had stage II tumors and about three-fourths (74.0%) presented with nodal involvement. About two-thirds of patients (66.0%) had estrogen receptor–positive disease, about half (56.9%) were progesterone receptor–positive, and 15.1% were human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive. Most of the patients (81.8%) were treated with chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting, whereas the remainder (18.2%) received neoadjuvant therapy.

Cox regression analysis involving all patients in the dataset showed that capecitabine was not associated with a significant improvement in DFS, nor was a significant improvement seen in trials that compared capecitabine against other treatment options. In contrast, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment supported a modest but significant improvement in DFS (hazard ratio, 0.888; P = .0005).

Across all patients, capecitabine was associated with an overall survival advantage, although this benefit was relatively small, with a hazard ratio of 0.892. The overall survival benefit became more pronounced when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment (HR, 0.837).

Of clinical importance, biological subtype analysis showed that only patients with triple-negative breast cancer were deriving survival benefit from capecitabine, particularly when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment. Among patients with triple-negative disease, a 17% overall survival benefit was associated with capecitabine (HR, 0.828). When capecitabine was added to systemic treatment, this survival advantage improved to 22% (HR, 0.778).

No relationship was found between capecitabine-specific toxicity (mucositis, hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea) and patient outcome.

“It can be concluded that the addition of capecitabine to other systemic treatment may be recommended for triple-negative breast cancer patients,” Dr. Mackelenbergh said.

Invited discussant Priyanka Sharma, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City agreed with this conclusion.

“Routine use of capecitabine as a component of neoadjuvant or adjuvant regimens in unselected patients cannot be endorsed,” Dr. Sharma said. “However, capecitabine should be considered in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, especially if response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is utilized as a way to identify eligible patients so as to limit exposure and toxicity to those at the highest risk.”

In terms of the future, Dr. Sharma suggested that research is needed to determine the potential for adjuvant capecitabine among patients with triple-negative breast cancer who have received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy as part of their neoadjuvant regimen. In addition, investigators should evaluate capecitabine efficacy in terms of residual disease and identify relevant predictive biomarkers, Dr. Sharma said.

The investigators reported relationships with Amgen, Lilly, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: van Mackelenbergh M et al. SABCS 2019, Abstract GS1-07.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment may extend overall survival, according to a meta-analysis involving more than 15,000 patients.

Although a variety of trials have tested capecitabine therapy for early-stage breast cancer, this study is the first to evaluate individual patient data across trials, reported lead author Marion van Mackelenbergh, MD, of University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany, and colleagues.

According to Dr. Mackelenbergh, who presented findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, the two previous literature-based meta-analyses of capecitabine for patients with early-stage breast cancer reported conflicting results; the first study suggested that capecitabine had no benefit as a neoadjuvant therapy, whereas the second study concluded that capecitabine could improve disease-free survival (DFS).

To build upon these findings, the primary objective of the present meta-analysis was to determine how treatment with capecitabine impacts DFS, Dr. Mackelenbergh said. A variety of secondary objectives were also evaluated, including overall survival and a possible interaction between capecitabine-specific toxicities and treatment effects.

The analysis involved 15,457 patients from 12 randomized prospective clinical trials, of whom about half (n = 7,477) were treated in control arms. Slightly more than half (55.9%) of the patients had stage II tumors and about three-fourths (74.0%) presented with nodal involvement. About two-thirds of patients (66.0%) had estrogen receptor–positive disease, about half (56.9%) were progesterone receptor–positive, and 15.1% were human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive. Most of the patients (81.8%) were treated with chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting, whereas the remainder (18.2%) received neoadjuvant therapy.

Cox regression analysis involving all patients in the dataset showed that capecitabine was not associated with a significant improvement in DFS, nor was a significant improvement seen in trials that compared capecitabine against other treatment options. In contrast, adding capecitabine to systemic treatment supported a modest but significant improvement in DFS (hazard ratio, 0.888; P = .0005).

Across all patients, capecitabine was associated with an overall survival advantage, although this benefit was relatively small, with a hazard ratio of 0.892. The overall survival benefit became more pronounced when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment (HR, 0.837).

Of clinical importance, biological subtype analysis showed that only patients with triple-negative breast cancer were deriving survival benefit from capecitabine, particularly when capecitabine was added to systemic treatment. Among patients with triple-negative disease, a 17% overall survival benefit was associated with capecitabine (HR, 0.828). When capecitabine was added to systemic treatment, this survival advantage improved to 22% (HR, 0.778).

No relationship was found between capecitabine-specific toxicity (mucositis, hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea) and patient outcome.

“It can be concluded that the addition of capecitabine to other systemic treatment may be recommended for triple-negative breast cancer patients,” Dr. Mackelenbergh said.

Invited discussant Priyanka Sharma, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City agreed with this conclusion.

“Routine use of capecitabine as a component of neoadjuvant or adjuvant regimens in unselected patients cannot be endorsed,” Dr. Sharma said. “However, capecitabine should be considered in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, especially if response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is utilized as a way to identify eligible patients so as to limit exposure and toxicity to those at the highest risk.”

In terms of the future, Dr. Sharma suggested that research is needed to determine the potential for adjuvant capecitabine among patients with triple-negative breast cancer who have received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy as part of their neoadjuvant regimen. In addition, investigators should evaluate capecitabine efficacy in terms of residual disease and identify relevant predictive biomarkers, Dr. Sharma said.

The investigators reported relationships with Amgen, Lilly, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: van Mackelenbergh M et al. SABCS 2019, Abstract GS1-07.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2019

Evidence builds for effects of obesity, low physical activity on development of psoriatic arthritis

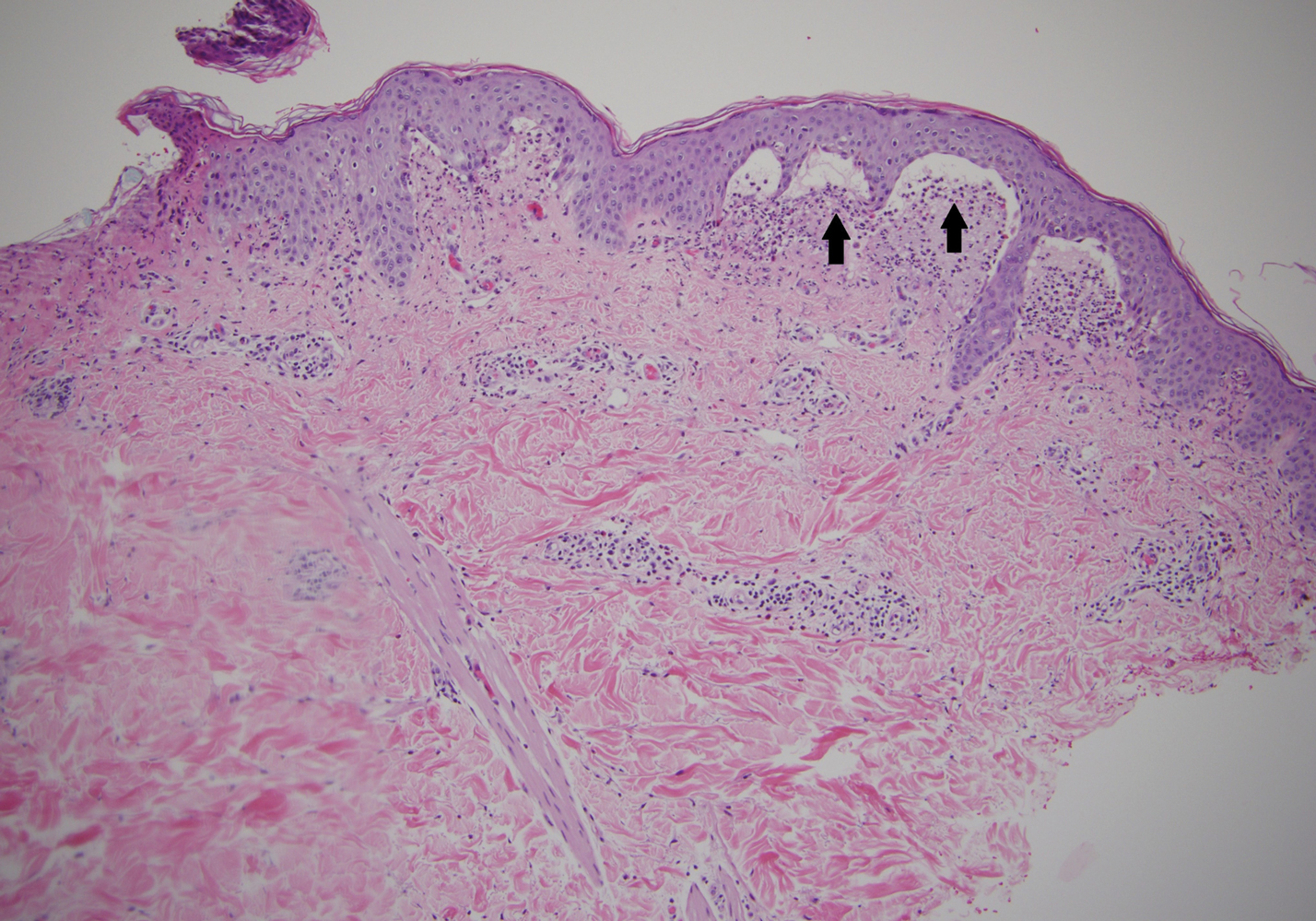

A new Norwegian study has identified a high body mass index and lower levels of physical activity as modifiable risk factors for developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“Our study adds to the growing evidence that the risk of PsA is modifiable and highlights the importance of preventive work against obesity as well as encouraging physical activity in order to reduce the incidence of PsA,” wrote Ruth S. Thomsen, MD, of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine the impact that adiposity and body fat distribution have on developing PsA, the researchers analyzed data from 36,626 women and men who participated in two surveys from the longitudinal, population-based Norwegian HUNT Study. All participants did not have diagnosed PsA at baseline in 1995-1997. Variables used in statistical analysis included calculated baseline BMI, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and level of physical activity.

Between baseline and follow-up in 2012, 185 new cases of PsA were reported. One standard deviation increase in BMI (4.2 kg/m2 for women, 3.5 kg/m2 for men) and waist circumstance (10.8 cm for women, 8.6 cm for men) was associated with adjusted hazard ratios of 1.40 (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.58) and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.31-1.68), accordingly. Obese individuals – defined as BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher – had an adjusted HR of 2.46 (95% CI, 1.65-3.68) when compared with individuals at normal weight.

Compared to individuals with BMI less than 25 kg/m2 and a high level of physical activity, individuals with BMI at 25 kg/m2 or higher and any lower level of physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.06 (95% CI, 1.18-3.58). In addition, individuals with a high waist circumference – defined as 81 cm or more in women and 95 cm or more in men – and low physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.37-3.58) in comparison to those with a high waist circumference and high physical activity (adjusted HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.97-3.47). Physical activity level was considered low with less than 3 hours of light physical activity and no hard physical activity per week and high with any amount of light activity plus 1 or more hours of hard physical activity.

The authors acknowledged the study’s potential limitations, including the requirement for participants to complete the final two HUNT study surveys and the use of stricter criteria than usual in validating PsA diagnoses.

The study was partially funded by a grant Dr. Thomsen received from the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thomsen RS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Dec 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.24121.

A new Norwegian study has identified a high body mass index and lower levels of physical activity as modifiable risk factors for developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“Our study adds to the growing evidence that the risk of PsA is modifiable and highlights the importance of preventive work against obesity as well as encouraging physical activity in order to reduce the incidence of PsA,” wrote Ruth S. Thomsen, MD, of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine the impact that adiposity and body fat distribution have on developing PsA, the researchers analyzed data from 36,626 women and men who participated in two surveys from the longitudinal, population-based Norwegian HUNT Study. All participants did not have diagnosed PsA at baseline in 1995-1997. Variables used in statistical analysis included calculated baseline BMI, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and level of physical activity.

Between baseline and follow-up in 2012, 185 new cases of PsA were reported. One standard deviation increase in BMI (4.2 kg/m2 for women, 3.5 kg/m2 for men) and waist circumstance (10.8 cm for women, 8.6 cm for men) was associated with adjusted hazard ratios of 1.40 (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.58) and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.31-1.68), accordingly. Obese individuals – defined as BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher – had an adjusted HR of 2.46 (95% CI, 1.65-3.68) when compared with individuals at normal weight.

Compared to individuals with BMI less than 25 kg/m2 and a high level of physical activity, individuals with BMI at 25 kg/m2 or higher and any lower level of physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.06 (95% CI, 1.18-3.58). In addition, individuals with a high waist circumference – defined as 81 cm or more in women and 95 cm or more in men – and low physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.37-3.58) in comparison to those with a high waist circumference and high physical activity (adjusted HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.97-3.47). Physical activity level was considered low with less than 3 hours of light physical activity and no hard physical activity per week and high with any amount of light activity plus 1 or more hours of hard physical activity.

The authors acknowledged the study’s potential limitations, including the requirement for participants to complete the final two HUNT study surveys and the use of stricter criteria than usual in validating PsA diagnoses.

The study was partially funded by a grant Dr. Thomsen received from the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thomsen RS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Dec 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.24121.

A new Norwegian study has identified a high body mass index and lower levels of physical activity as modifiable risk factors for developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“Our study adds to the growing evidence that the risk of PsA is modifiable and highlights the importance of preventive work against obesity as well as encouraging physical activity in order to reduce the incidence of PsA,” wrote Ruth S. Thomsen, MD, of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine the impact that adiposity and body fat distribution have on developing PsA, the researchers analyzed data from 36,626 women and men who participated in two surveys from the longitudinal, population-based Norwegian HUNT Study. All participants did not have diagnosed PsA at baseline in 1995-1997. Variables used in statistical analysis included calculated baseline BMI, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and level of physical activity.

Between baseline and follow-up in 2012, 185 new cases of PsA were reported. One standard deviation increase in BMI (4.2 kg/m2 for women, 3.5 kg/m2 for men) and waist circumstance (10.8 cm for women, 8.6 cm for men) was associated with adjusted hazard ratios of 1.40 (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.58) and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.31-1.68), accordingly. Obese individuals – defined as BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher – had an adjusted HR of 2.46 (95% CI, 1.65-3.68) when compared with individuals at normal weight.

Compared to individuals with BMI less than 25 kg/m2 and a high level of physical activity, individuals with BMI at 25 kg/m2 or higher and any lower level of physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.06 (95% CI, 1.18-3.58). In addition, individuals with a high waist circumference – defined as 81 cm or more in women and 95 cm or more in men – and low physical activity had an adjusted HR of 2.22 (95% CI, 1.37-3.58) in comparison to those with a high waist circumference and high physical activity (adjusted HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.97-3.47). Physical activity level was considered low with less than 3 hours of light physical activity and no hard physical activity per week and high with any amount of light activity plus 1 or more hours of hard physical activity.

The authors acknowledged the study’s potential limitations, including the requirement for participants to complete the final two HUNT study surveys and the use of stricter criteria than usual in validating PsA diagnoses.

The study was partially funded by a grant Dr. Thomsen received from the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thomsen RS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Dec 7. doi: 10.1002/acr.24121.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Phase 2 studies show potential of FcRn blockade in primary ITP