User login

Understanding Principles of High Reliability Organizations Through the Eyes of VIONE, A Clinical Program to Improve Patient Safety by Deprescribing Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Reducing Polypharmacy

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

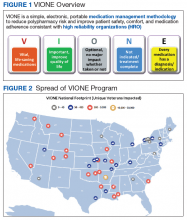

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

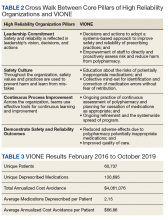

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

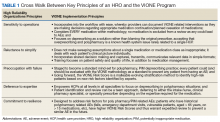

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact vavione@va.gov.

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

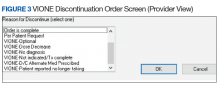

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

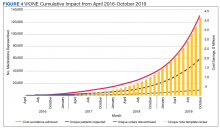

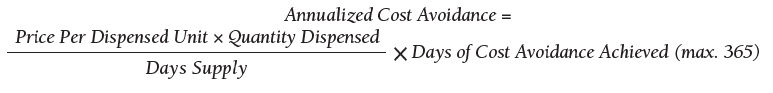

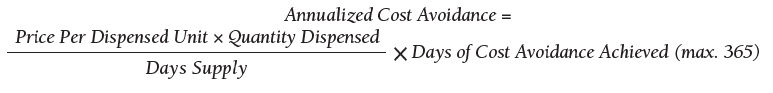

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact vavione@va.gov.

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact vavione@va.gov.

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

Aging and Trauma: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Korean War Veterans

The Korean War lasted from June 25, 1950 through July 27, 1953. Although many veterans of the Korean War experienced traumas during extremely stressful combat conditions. However, they would not have been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at the time because the latter did not exist as a formal diagnosis until the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1980.1 Prior to 1980, psychiatric syndromes resulting from war and combat exposure where known by numerous other terms including shell shock, chronic traumatic war neurosis, and combat fatigue/combat exhaustion.2,3 Military psychiatrists attended to combat fatigue during the course of the Korean War, but as was true of World War I and II, the focus was on returning soldiers to duty. Combat fatigue was generally viewed as a transient condition.4-8

Although now octo- and nonagenarians, in 2019 there are 1.2 million living Korean War veterans in the US, representing 6.7% of all current veterans.9 Understanding their war experiences and the nature of their current and past presentation of PTSD is relevant not only in formal mental health settings, but in primary care settings, including home-based primary care, as well as community living centers, skilled nursing facilities and assisted living facilities. Older adults with PTSD often present with somatic concerns rather than spontaneously reporting mental health symptoms.10 Beyond the short-term clinical management of Korean War veterans with PTSD, consideration of their experiences also has long-term relevance for the appropriate treatment of other veteran cohorts as they age in coming decades.

The purpose of this article is to provide a clinically focused overview of PTSD in Korean War veterans, to help promote understanding of this often-forgotten group of veterans, and to foster optimized personalized care. This overview will include a description of the Korean War veteran population and the Korean War itself, the manifestations and identification of PTSD among Korean War veterans, and treatment approaches using evidence-based psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies. Finally, we provide recommendations for future research to address present empirical gaps in the understanding and treatment of Korean War veterans with PTSD.

Causes and Course of the Korean War

When working with Korean War veterans it is important to consider the special nature of that specific conflict. Space considerations limit our ability to do justice to the complex history and numerous battles of the Korean War, but information in the following summary was gleaned from several excellent histories.11-13

The Korean War has been referred to as The Forgotten War, a concern expressed even during the latter parts of the war.14,15 But the war and its veterans warrant remembering. The root and proximal causes of the Korean War are complex and not fully agreed upon by the main participants.16-19 In part this may reflect the fact that there was no clear victor in the Korean War, so that the different protagonists have developed their own versions of the history of the conflict. Also, US involvement and the public reaction to the war must be viewed within the larger historical context of that time. This context included the recent end of 4 years of US involvement in World War II (1941-1945) and the subsequent rapid rise of Cold War tensions between the US and the Soviet Union. The latter also included a worldwide fear of nuclear war and the US fear of the global spread of communism. These fears were fueled by the Soviet-led Berlin Blockade from June 1948 through May 1949, the Soviet Union’s successful atomic bomb test in August 1949, the founding of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, and the February 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.13

In the closing days of World War II, the US and Soviet Union agreed to a temporary division of Korea along the 38th parallel to facilitate timely and efficient surrender of Japanese troops. But as Cold War tensions rose, the temporary division became permanent, and Soviet- and US-backed governments of the north and south, respectively, were officially established on the Korean peninsula in 1948. Although by 1949 the Soviets and US had withdrawn most troops from the peninsula, tensions between the north and south continued to mount and hostilities increased. To this day the exact causes of the eruption of war remain disputed, although it is clear that ideological as well as economic factors played a role, and both leaders of North and South Korea were pledging to reunite the peninsula under their respective leadership.16-19 The tension culminated on June 25, 1950, when North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea. On June 27, 1950, President Truman ordered US naval and air forces to support South Korea and then ordered the involvement of ground troops on June 30.16,17,19

Although several other member countries of the United Nations (UN) provided troops, 90% of the troops were from the US. About 5.7 million US military personnel served during the war, including about 1.8 million in Korea itself. The US forces experienced approximately 34,000 battle-related deaths, 103,000 were wounded, and 7,000 were prisoners of war (POWs).11,20-22 The nature and events of the Korean War made it particularly stressful and traumatizing for the soldiers, sailors, and marines involved throughout its entire course. These included near defeat in the early months, a widely alternating war front along the north/south axis during the first year, and subsequently, not only intense constant battles on the fronts, but also a demanding and exhausting guerrilla war in the south, which lasted throughout the remainder of the conflict.11,15 The US troops during the initial months of the war have been described as outnumbered and underprepared, as many in the initial phase were reassigned from peace-time occupation duty in Japan.7

The first year of war was characterized by a repeated north-to-south/south-to-north shifts in control of territory. During the first 3 months, the North Korean forces overwhelmed the South and captured control of all but 2 South Korean cities in the far southeastern region (Pusan, now Busan; and Daegu), and US and UN forces were forced to retreat to the perimeter around Pusan. The intense Battle of Pusan Perimeter lasted from August 4, 1950 to September 18, 1950, and resulted in massive causalities as well as a flood of civilian refugees.

The course of the war began to change in early September 1950 with the landing of amphibious US/UN forces at Inchon, behind North Korean lines, which cut off southern supply routes for the North Korean troops.11 US/UN forces soon crossed to the north of the 38th parallel and captured the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, on October 19, 1950. They continued to push north and approached the Yalu River border with China by late November 1950, but then the Chinese introduced their own troops forcing a southward retreat of US/UN troops during which there were again numerous US/UN casualties. Chinese troops retook Seoul in late December 1950/early January 1951. However, the US/UN forces soon recaptured Seoul and advanced back to the 38th parallel. This back-and-forth across the 38th parallel continued until July 1951 when the front line of battle stabilized there. Although the line stabilized, intense battles and casualties continued for 2 more years. During this period US/UN troops also had to deal with guerrilla warfare behind the front lines due to the actions of communist partisans and isolated North Korean troops. This situation continued until the armistice was signed July 27, 1953.

Trauma and Characteristic Stresses of the War

There were many factors that made the Korean War experience different from previous wars, particularly World War II. For example, in contrast to the strong public support during and after World War II, public support for the Korean War in the US was low, particularly during its final year.23 In public opinion polls from October 1952 through April 1953, only 23% to 39% reported feeling that the war was worth fighting.23 A retrospective 1985 survey also found that 70% of World War II veterans, but only 33% of Korean War veterans reported feeling appreciated by the US public on their return from the war.24

Those fighting in the initial months of the war faced a particularly grim situation. According to LTC Philip Smith, who served as Division Psychiatrist on the Masan Front (Pusan Perimeter) during August and September of 1950, “Fighting was almost continuous and all available troops were on the fighting front… For the most part these soldiers were soft from occupation duty, many had not received adequate combat basic training, no refresher combat training in Korea had as yet been instituted,” he reported.7 “The extremes of climate coupled with the generally rugged mountainous terrain in Korea were physical factors of importance…These men were psychologically unprepared for the horrors and isolation of war.” LTC Smith noted that the change in status from civilian or occupation life to the marked deprivation of the war in Korea had been “too abrupt to allow as yet for a reasonable adjustment to the new setting” and that as a result “the highest rate of wounded and neuropsychiatric casualties in the Korean campaign resulted.”7

Even after this initial period, the nature of the shifting war, the challenging terrain, the high military casualty rate, and the high rate of civilian casualties and displacement continued throughout the war.

PTSD in Korean War Veterans

It is clear that Korean War combat veterans were exposed to traumatic events. It is unknown how many developed PTSD. While notions of psychological distress and disability related to combat trauma exposure have existed for centuries, Korean War and World War II veterans are a remaining link to pre-DSM PTSD mental health in the military. Military/forward psychiatry—psychiatric services near the battle zone rather than requiring evacuation of patients—was present in Korea from the early months of the war, but the focus of forward psychiatry was to reduce psychiatric causalities from combat fatigue and maximize rapid return-to-duty.4-6 With no real conception of PTSD, there were limited treatments available, and evidenced-based trauma-focused treatments for PTSD would not be introduced for at least another 4 decades.27-29

Skinner and Kaplick conducted a historical review of case descriptions of trauma-related conditions from World War I through the Vietnam War and noted the consistent inclusion of hyperarousal and intrusive symptoms, although there also was a greater emphasis on somatic conversion or hysteria symptoms in the earlier descriptions.30 By the Korean War, descriptions of combat fatigue included a number of symptoms that overlap with PTSD, including preoccupation with the traumatic stressor, nightmares, irritability/anger, increased startle, and hyperarousal.31 But following the acute phases, attention to any chronic problems associated with these conditions waned. As was acknowledged by a military psychiatrist in a 1954 talk, studies of the long-term adjustment of those who had “broken down in combat” were sorely needed.6 In a small 1965 study reported by Archibald and Tuddenham, persistent symptoms of combat fatigue among Korean War veterans were definitely present, and there was even a suggestion that the symptoms had increased over the decade since the war.32

Given the stoicism that typified cultural expectations for military men during this period, Korean War veterans may also have been reluctant to seek mental health treatment either at the time or later. In short, it is likely that a nontrivial proportion of Korean War veterans with PTSD were underdiagnosed and received suboptimal or no mental health treatment for decades following their war experiences.33 Although the nature of the war, deployment, and public support were distinct in World War II vs the Korean War, the absence of attention to the long-term effects of disorders related to combat trauma and the cultural expectations for stoicism suggest that PTSD among aging World War II veterans may also have gone underrecognized and undertreated.

Apart from the lack of interest in chronic effects of stressors, another problem that has plagued the limited empirical research on Korean War veterans has been the propensity to combine Korean War with World War II veteran samples in studies. Because World War II veterans have outnumbered Korean War veterans until recently, combined samples tended to have relatively few Korean War veterans. Nevertheless, from those studies that have been reported in which 2 groups were compared, important differences have been revealed. Specifically, although precise estimates of the prevalence of PTSD among Korean War combat veterans have varied depending on sampling and method, studies from the 1990s and early 2000s suggested that the prevalence of PTSD and other mental health concerns as well as the severity of symptoms, suicide risk, and psychosocial adjustment difficulties were worse among Korean War combat veterans relative to those among World War II combat veterans; however, both groups had lower prevalence than did Vietnam War combat veterans.21,34-37 Several authors speculated that these differences in outcome were at least partially due to differences in public support for the respective wars.36,37

Although there has been a paucity of research on psychiatric issues and PTSD in Korean War veterans, POWs who were very likely to have been exposed to extreme psychological traumas have received some attention. There have been comparisons of mortality and morbidity among POWs from the Korean War (PWK), World War II Pacific Theater (PWJ), and Europe (PWE).38 Among measures that were administered to the former POWs, the overall pattern seen from survey data in the mid-1960s revealed significantly worse health and functioning among the PWK and PWJ groups relative to the PWE group, with psychiatric difficulties being the most commonly reported impairments among the former 2 groups. This pattern was found most strongly with regards to objective measures, such as hospitalizations for “psychoneuroses,” and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) disability records, as well as based on self-reported psychosocial/recreational difficulties measured using the Cornell Medical Index (CMI).38

Gold and colleagues reported a follow-up study of more than 700 former POWs who were reinterviewed between 1989 and 1992.39 Although there was no scale of PTSD symptoms prior to formulation of the diagnosis in 1980, the CMI was a self-reported checklist that included a large range of both medical as well as behavioral and psychiatric symptoms. Thus, using CMI survey responses from 1965, the authors examined the factor structure (ie, the correlational relationships between multiple scale items and subgroupings of items) of the CMI relative to diagnosis of PTSD in 1989 to 1992 based on results from the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R (SCID). The intent was to help discern whether the component domains of PTSD were present and intercorrelated in a pattern similar to that of the contemporary diagnosis. The investigators examined the factor structure of 20 psychological items from the CMI that appeared relevant to PTSD criteria using the 1965 data. Three factors (subgroups of highly intercorrelated items) were found: irritability (31% of variance), fearfulness/anxiousness (9% of the variance), and social withdrawal (7% of the variance). Although these did not directly correspond to, or fully cover, DSM PTSD domains or criteria, there does appear to be a thematic resemblance of the CMI findings with PTSD, including alterations in arousal and mood, vigilance, and startle.

Identification and Treatment of PTSD in Older Veterans

Of the 1.2 million living Korean War veterans in the US, 36.3% use VA provided health care.40 There are a number of complicating factors to consider in the current identification and treatment of PTSD in this cohort, including their advanced age; physical, cognitive, and social changes associated with normal aging; the associated medical and cognitive comorbidities; and the specific social-contextual factors in that age cohort. Any combination of these factors may complicate recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. It is also important to be cognizant of the additional stressors that may have been experienced by ethnic minorites and women serving in Korea, which are poorly documented and studied. Racial integration of the US military began during the Korean War, but the general pattern was for African American soldiers to be assigned to all-white units, rather than the reverse.14,41,42 And although the majority of military personnel serving in Korea were male, there were women serving in health care positions at mobile army surgical hospital (MASH) units, medical air evacuation (Medevac) aircraft, and off-shore hospital ships.

The clinical presentation of PTSD in older adults has varied, which may partially relate to the time elapsed since the index trauma. For example, older veterans in general may show less avoidance behavior as a part of PTSD, but in those who experience trauma later in life there may actually be greater avoidance.43,44 There have also been discrepant reports of intrusion or reexperiencing of symptoms, with these also potentially reduced in older veterans.43,44 However, sleep disturbances seem to be very common among elderly combat veterans, and attention should be paid to the possible presence of sleep apnea, which may be more common in veterans with PTSD in general.43,45,46

PTSD symptoms may reemerge after decades of remission or quiescence during retirement and/or with the emergence of neurocognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer disease or dementia. These individuals may have more difficulty engaging in distracting activities and work and spend more time engaging in reminiscence about the past, which can include increased focus on traumatic memories.45,47 Davison and colleagues have suggested a concept they call later-adulthood trauma reengagement (LATR) where later in life combat veterans may “confront and rework their wartime memories in an effort to find meaning and build coherence.”48 This process can be a double-edged sword, leading at times positively to enhanced personal growth or negatively to increased symptoms; preventive interventions may be able foster a more positive outcome.48

There is some evidence supporting the validity of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for the evaluation of PTSD in older adults, although this was based on the DSM-III-revised criteria for PTSD and an earlier version of CAPS.49 Bhattarai and colleagues examined responses to the 35-item Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD) using VA clinical data collected between 2008 and 2015 on veterans of each combat era from World War II through the post-9/11.50 Strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the M-PTSD was observed within each veteran era sample. However, using chart diagnosis of PTSD as the criterion standard, the cut-scores for optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity of the M-PTSD scores were substantially lower for the older cohorts (World War II and Korean War veterans) relative to those for Vietnam and more recent veteran cohorts. The authors concluded that M-PTSD can be validly used to screen for PTSD in veterans within each of these cohorts but recommended using lower than standard cut-scores for Korean War and World War II veterans.50

This is also consistent with reports that suggest the use of lower cut-scores on self-administered PTSD symptom screens.43,44 For the clinician interested in quantifying the severity of PTSD, the most recent tools available are the CAPS-5 and the PCL-5, which have both been created in accordance with the DSM-5. The CAPS-5 is a rater-administered tool, and the PCL-5 is self-administered by the veteran. Although there has been little research using these newer tools in geriatric populations, they can currently serve as a means of tracking the severity of PTSD while we await measures that are better validated in Korean War and other older veterans.

Beyond specific empirical guidance, VA clinicians must presently rely on clinical observations and experience. Patients from the Korean War cohort often present at the insistence of a family member for changes in sleep, mood, behavior, or cognition. When the veterans themselves present, older adults with PTSD often focus more on somatic concerns (including pain, sleep, and gastrointestinal disturbance) than psychiatric problems per se. The latter tendency may in part be due to the salience of such symptoms for them, but perhaps also due to considerable stigma of mental health care that is still largely present in this group.43,44

Psychotherapy

Current VA treatment guidelines recommend trauma-focused therapies, with the strongest evidence base for prolonged exposure (PE), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapies.51

There have been several excellent prior reviews discussing treatment of PTSD in older adults generally.10,43,44,52 These reviews have invariably expressed concern about the lack of sufficient empirical studies, but based on evidence from studies and case reports, there seems to be tentative support that trauma-focused therapies are acceptable and efficacious for use with older adults with PTSD. In their recent scoping review, Pless Kaiser and colleagues made several recommendations for trauma-focused therapy with older adults, including slow/careful pacing and use of compensatory aids for cognitive and sensory deficits.44 When cognitive impairment has exacerbated PTSD symptoms, they suggest therapists consider using an adapted form of CPT completed without a trauma narrative. For PE they recommend extending content across sessions and involving spouse or caregivers to assist with in vivo exposure and homework completion.44

Recent studies suggest that PTSD may be a risk factor for the later development of neurodegenerative disorders, and it is often during assessments for dementia that a revelation of PTSD occurs.10,43,47,55 Cognitive impairment may also be of relevance in deciding on the type of psychotherapy to be implemented, as it may have more adverse effects on the effectiveness of CPT than of exposure-based treatments (PE or EMDR). It may be useful to perform a cognitive assessment prior to initiation of a cognitive-based therapy, although extensive cognitive testing may not be practical or may be contraindicated because of fatigue. A brief screening tool such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or the Mini-Mental State Examinationmay be helpful.56, 57

Prolonged exposure has been reported by many clinicians to be effective in older adults with PTSD; however, due consideration should be given to the needs of individuals, as many have functioned for decades by suppressing memories.

Apart from the treatment needs for specific PTSD symptoms, the decades-long effects of poor sleep, irritability, hypervigilance, and dissociation also have social consequences for patients, including marital discord and divorce, and social and family isolation that should be addressed in therapy when appropriate. In addition, many Korean War veterans, like all veterans, sought postmilitary employment in professions that are associated with higher rates of exposure to psychological trauma, such as police or fire departments, and this may have an exacerbating effect on PTSD.58

Pharmacotherapy

There is very little empirical evidence guiding pharmacologic approaches to PTSD in older veterans. This population is at increased risk for many comorbidities, and pharmacologic treatments many require dosage adjustments, as is the case for any geriatric patient. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) medications have been proposed for some cases of PTSD.59,60 Health care providers may consider the SSRIs escitalopram or sertraline preferentially given their decreased potential for drug-drug interactions, anticholinergic effects, or cardiac toxicity compared with that of other drugs in this class.60,61 As venlafaxine can increase blood pressure, especially at higher doses, prescribers may choose duloxetine as an alternative if a SNRI is indicated.60 For veterans when prazosin is being considered for nightmare control, monitoring for hypotension, orthostasis, and the administration of other antihypertensives or prostatic hypertrophy medications is necessary.61 The use of benzodiazepines, while not recommended for PTSD, should be viewed with even greater trepidation in a geriatric population given enhanced risk of falls and confusion in the geriatric veteran population.60,62

Conclusions

Many of the oldest veterans (aged > 80 years) are from the Korean War era. The harsh and unique nature of the war, as well as the differences in context and support from the US public, and the outcome of the war, may have all contributed to and elevation of “combat fatigue” and PTSD among combat veterans from the Korean War. As the “forgotten war” cohort also has been forgotten by researchers, relatively little is known about posttraumatic stress sequelae of these veterans in the decades following the war.

From available evidence, we can readily surmise that problems were underrecognized and suboptimally diagnosed and treated. There is tentative evidence supporting the use of standard interviews and rating scales, such as the CAPS, M-PTSD, and PCL, but lower cut-scores than applied with Vietnam and later veteran cohorts are generally recommended to avoid excessive false negative errors. In terms of psychotherapy treatment, there is again a stark paucity of systematic research, but the limited evidence from studies of PTSD treatment in older adults from the general population tentatively support the acceptability and potential efficacy of recognized evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapies for PTSD. Research on medication treatment is similarly lacking, but the general recommendations for the use of SSRI or SNRI medications seem to be valid, at least in our clinical experience, and the general rules for geriatric psychopharmacology definitely apply here—start low, go slow.

There are several important avenues for future research. Most pressing among these are establishing the effectiveness of existing treatments, and the modifications that may be needed in the broader context of the above factors, as well as the physical and cognitive changes associated with advanced age. Further research on the phenomenologic aspects of PTSD among Korean War and subsequent cohorts are also needed, as the information obtained will not only guide more effective personalized treatment of the Korean War veterans who remain with us, but also inform future generations of care in terms of the degree and dimensions of variability that may present between cohorts and within cohorts over the life span.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

2. Friedman MJ, Schnurr PP, McDonagh-Coyle A. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the military veteran. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1994;17(2):265-277.

3. Salmon TW. The Care and Treatment of Mental Diseases and War Neuroses (“Shell Shock”) in the British Army. New York: War Work Committee of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, Inc; 1917.

4. Jones E, Wessely S. “Forward psychiatry” in the military: its origins and effectiveness. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(4):411-419.

5. Newman RA. Combat fatigue: a review to the Korean conflict. Mil Med. 1964;129:921-928.

6. Harris FG. Some comments on the differential diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric breakdowns in Korea. https://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/korea/recad2/ch9-2.html. Published April 30, 1954. Accessed November 8, 2019.

7. Smith PB. Psychiatric experiences during the Korean conflict. Am Pract Dig Treat. 1955;6(2):183-189.

8. Koontz AR. Psychiatry in the Korean War. Military Surg.

1950;107(6):444-445.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population Tables - Table 2L: VETPOP2016 Living Veterans by period of service, gender, 2015-2045. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Demographics/New_Vetpop_Model/2L_VetPop2016

_POS_National.xlsx. Accessed November 8, 2019.

10. Cook JM, McCarthy E, Thorp SR. Older adults with PTSD: brief state of research and evidence-based psychotherapy case illustration. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(5):522-530.

11. Millett AR. Korean War: 1950-1953. Encylopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Korean-War#accordion-article-history. Updated Nov 7, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2019.

12. Stack L. Korean War, a ‘forgotten’ conflict that shaped the modern world. The New York Times. January 2, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/01/world/asia/korean-war-history.html. Accessed November 8, 2019.

13. Westad OA. The Cold War: A World History. New York: Basic Books; 2018.

14. Young C, Conard PL, Armstrong ML, Lacy D. Older military veteran care: many still believe they are forgotten. J Holist Nurs. 2018;36(3):291-300.

15. Huebner AJ. Kilroy is back, 1950-1953. In: The Warrior Image: Soldiers in American Culture From the Second World War to the Vietnam Era. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press; 2008:97-131.

16. The annexation of Korea (editorial). Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2010/08/29/editorials/the-annexation-of-korea/#.XPgvJvlKhhE. Published August 29, 2010. Accessed November 8, 2019.

17. Gupta K. How did the Korean war begin? China Q. 1972;52:699-716.

18. Lin L, Zhao Y, Ogawa M, Hoge J, Kim BY. Whose history? An analysis of the Korean War in history textbooks from the United States, South Korea, Japan, and China. Social Studies. 2009;100(5):222-232.

19. Weathersby K. The Korean War revisited. Wilson Q. 1999;23(3):91.

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Program and Data Analyses, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Analysis. Data on veterans of the Korean War. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/KW2000.pdf. Published June 2000. Accessed November 8, 2019.

21. Brooks MS, Fulton L. Evidence of poorer life-course mental health outcomes among veterans of the Korean War cohort. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(2):177-183.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public Affairs. America’s wars. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2019.

23. Memorandum on recent polls on Korea. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/korean-war/public-opinion-1953-06-02.pdf. Published June 2, 1953. Accessed November 8, 2019.

24. Elder GH Jr, Clipp EC. Combat experience and emotional health: impairment and resilience in later life. J Pers. 1989;57(2):311-341.

25. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: cold injuries. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/PUBLICHEALTH/exposures/cold-injuries/index.asp. Updated July 31, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2019.

26. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Korean War veterans health issues. https://www.va.gov/health-care/health-needs-conditions/health-issues-related-to-service-era

/korean-war/. Updated June 14, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2019.

27. Shapiro F. Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. J Trauma Stress. 1989;2(2):199-223.

28. Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1992;60(5):748-756.

29. Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating Trauma of Rape: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford; 2001.

30. Skinner R, Kaplick PM. Cultural shift in mental illness: a comparison of stress responses in World War I and the Vietnam War. JRSM Open. 2017;8(12):2054270417746061.

31. Kardiner A, Spiegel H. War Stress and Neurotic Illness. New York: Hoeber; 1947.

32. Archibald HC, Tuddenham RD. Persistent stress reaction after combat: a 20-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:475-481.

33. Cook JM, Simiola V. Trauma and aging. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(10):93.

34. Rosenheck R, Fontana A. Long-term sequelae of combat in World War II, Korea and Vietnam: a comparative study. In: McCaughey BG, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, eds. Individual

and Community Responses to Trauma and Disaster: The Structure of Human Chaos. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994:330-359.

35. Blake DD, Keane TM, Wine PR, Mora C, Taylor KL, Lyons JA. Prevalence of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans seeking medical treatment. J Trauma Stress. 1990;3(1):15-27.

36. McCranie EW, Hyer LA. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Korean conflict and World War II combat veterans seeking outpatient treatment. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(3):427-439.

37. Fontana A, Rosenheck R. Traumatic war stressors and psychiatric symptoms among World War II, Korean, and Vietnam War veterans. Psychology Aging. 1994;9(1):27-33.

38. Beebe GW. Follow-up studies of World War II and Korean war prisoners. II. Morbidity, disability, and maladjustments. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;101(5):400-422.

39. Gold PB, Engdahl BE, Eberly RE, Blake RJ, Page WF, Frueh BC. Trauma exposure, resilience, social support, and PTSD construct validity among former prisoners of war. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(1):36-42.

40. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Key statistics by veteran status and period of service. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/KeyStats.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2019.

41. Bowers WT, Hammond WM, MacGarrigle GL. Black Soldier, White Army. Washington DC: US Army Center of Military History; 1996.

42. Black HK. Three generations, three wars: African American veterans. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):33-41.

43. Thorp SR, Sones HM, Cook JM. Posttraumatic stress disorder among older adults. In: Sorocco KH, Lauderdale S, eds. Cognitive Behavior Therapy With Older Adults: Innovations Across Care Settings. New York: Springer; 2011:189-217.

44. Pless Kaiser A, Cook JM, Glick DM, Moye J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults: a conceptual review. Clinical Gerontol. 2019;42(4):359-376.

45. Sadavoy J. Survivors. A review of the late-life effects of prior psychological trauma. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5(4):287-301.

46. Tamanna S, Parker JD, Lyons J, Ullah MI. The effect of continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) on nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):631-636.

47. Mota N, Tsai J, Kirwin PD, et al. Late-life exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in US veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):348-354.

48. Davison EH, Kaiser AP, Spiro A 3rd, Moye J, King LA, King DW. From Late-onset stress symptomatology to later-adulthood trauma reengagement in aging combat veterans: taking a broader view. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):14-21.

49. Hyer L, Summers MN, Boyd S, Litaker M, Boudewyns P. Assessment of older combat veterans with the clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):587-593.

50. Bhattarai JJ, Oehlert ME, Weber DK. Psychometric properties of the Mississippi Scale for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder based on veterans’ period of service. Psychol Serv. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]

51. US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DOD Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Version 3.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal012418.pdf.

Updated 2017. Accessed November 11, 2019.

52. Dinnen S, Simiola V, Cook JM. Post-traumatic stress disorder in older adults: a systematic review of the psychotherapy treatment literature. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(2):144-150.

53. Jakel RJ. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Elderly. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):165-175.

54. Thorp SR, Glassman LH, Wells SY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prolonged exposure therapy versus relaxation training for older veterans with military-related PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;64:45-54.

55. Kang B, Xu H, McConnell ES. Neurocognitive and psychiatric comorbidities of posttraumatic stress disorder among older veterans: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(4):522-538.

56. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.

57. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

58. Paton D. Traumatic Stress in Police Officers a Career-Length Assessment From Recruitment to Retirement. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2009.

59. Alexander W. Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in combat veterans: focus on antidepressants and atypical antipsychotic agents. P T. 2012;37(1):32-38.

60. Beck JG, Sloan DM, Friedman MJ. Pharmacotherapy for PTSD. In: The Oxford Handbook of Traumatic Stress Disorders. Oxford University Press; 2012.

61. Waltman SH, Shearer D, Moore BA. Management of posttraumatic nightmares: a review of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments since 2013. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(12):108.

62. Díaz-Gutiérrez MJ, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, Sáez de Adana E, et al. Relationship between the use of benzodiazepines and falls in older adults: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2017;101:17-22.

The Korean War lasted from June 25, 1950 through July 27, 1953. Although many veterans of the Korean War experienced traumas during extremely stressful combat conditions. However, they would not have been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at the time because the latter did not exist as a formal diagnosis until the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1980.1 Prior to 1980, psychiatric syndromes resulting from war and combat exposure where known by numerous other terms including shell shock, chronic traumatic war neurosis, and combat fatigue/combat exhaustion.2,3 Military psychiatrists attended to combat fatigue during the course of the Korean War, but as was true of World War I and II, the focus was on returning soldiers to duty. Combat fatigue was generally viewed as a transient condition.4-8