User login

Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy: Public health problem or lab finding with minimal clinical significance?

In a US study of more than 17,000 people, overt hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were detected in about 4.6% and 1.3% of adults, respectively.1 In this population-based study, thyroid disease was 5 times more prevalent among women than among men. In our ObGyn practices, there are many women of reproductive age with thyroid disease who are considering pregnancy. Treatment of active hyperthyroidism in a woman planning pregnancy is complex and best managed by endocrinologists. Treatment of hypothyroidism is more straightforward, however, and typically managed by internists, family medicine clinicians, and obstetrician-gynecologists.

Clinical management of hypothyroidism and pregnancy

Pregnancy results in a doubling of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) levels and a 40% increase in plasma volume, resulting in a need for more thyroxine production.2 Of note, from conception to approximately 13 weeks’ gestation, the sole source of embryonic and fetal thyroid hormones is from the mother.2 Women who have been taking chronic thyroxine treatment may have suppressed thyroid gland activity and be unable to increase thyroxine production in response to pregnancy, necessitating a 30% to 50% increase in their thyroxine dose to maintain TSH levels in the normal range.

For hypothyroid women on long-term thyroxine treatment, recommend increasing the thyroxine dose when pregnancy is recognized. For your patients on chronic thyroxine treatment who are planning a pregnancy, a multiprong approach is helpful in preparing the patient for the increased thyroxine requirements of early pregnancy. First, it is important to counsel the woman that she should not stop the thyroxine medication because it may adversely affect the pregnancy. In my experience, most cases of overt hypothyroidism during pregnancy occur because the patient stopped taking her thyroxine therapy. Second, for hypothyroid women who are considering conception it is reasonable to adjust the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration in the lower range of normal (0.5 to 2.5 mU/L). This will give the woman a “buffer,” reducing the risk that in early pregnancy she and her fetus will have a thyroxine deficit. Third, in early pregnancy, following detection of a positive pregnancy test, your patient can start to increase her thyroxine dose by about two tablets weekly (a 28% increase in the dose). Fourth, TSH levels can be measured every 4 weeks during the first trimester, with appropriate adjustment of the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration below the trimester-specific upper limit of normal (< 4 mU/L).2

TSH and free thyroxine measurements identify women with overt hypothyroidism who need thyroxine treatment. Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, including decreased fertility, increased spontaneous abortion, increased fetal loss, and preterm birth.2,3 Hence it is important to immediately initiate thyroxine treatment in pregnant women who have overt hypothyroidism. A diagnosis of overt hypothyroidism is indicated in women with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary axis and a TSH level ≥10 mU/L plus a low free thyroxine concentration. A TSH level of >4 to 10 mU/L, with normal free thyroxine concentration, is evidence of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH). Among women, there are about 5 times more cases of SCH than overt hypothyroidism.

Continue to: The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy...

The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy is vast, and often contradictory, leading to confusion among clinicians. Contributing to the confusion is that some observational studies report a modest association between SCH and adverse pregnancy outcomes. To date, however, randomized clinical trials show no benefit of thyroxine treatment in these cases. I explore these contradictory pieces of evidence below.

Is SCH associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes due to low thyroxine levels?

There is conflicting literature about the association of SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes. A meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with SCH and euthyroid women (normal TSH and normal free thyroxine levels) was 6.1% and 5.0%, respectively (odds ratio [OR], 1.29; 95% CI, 1.01–1.64).4 Interestingly, pregnant women with normal TSH levels but a low free thyroxine level also had an increased rate of preterm birth (7.1% vs 5.0%; OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.12–1.90).

Although observational studies report an association between SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes, multiple randomized clinical trials conducted in women with SCH or hypothyroxinemia have failed to demonstrate that thyroxine replacement improves reproductive outcomes. For example, in a study of 794 pregnant women with elevated TSH and/or low free thyroxine levels randomly assigned to thyroxine treatment (0.15 mg daily) or no treatment, there was no difference in preterm birth rate (5.6% vs 7.9%, P = .2), mean birth weight (3.5 kg vs 3.3 kg, P = .15), gestational age at delivery (40.1 vs 40.2 weeks, P = .10), or the intelligence quotient of children at 3 years (99 vs 100, P = .40).5

In another study, 674 pregnant women with mild SCH (mean TSH, 4.4 mU/L) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (0.1 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal TSH level) or placebo. In this study there was no difference between the thyroxine treatment or placebo groups in preterm birth rate (9% vs 11%, P = .44), gestational age at delivery (39.1 vs 38.9 weeks, P = .57) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (97 and 94, P = .71).6

The same investigators also randomized 524 pregnant women with isolated hypothyroxinema (mean free thyroxine level, 0.83 ng/dL) and normal TSH level (mean, 1.5 mU/L) to thyroxine (0.05 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal free thyroxine level) or placebo.6 In this study there was no difference in preterm birth rate (12% vs 8%, P = .11), gestational age at delivery (39.0 vs 38.8 weeks, P = .46) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (94 and 91, P = .31).6

When large randomized clinical trials and observational studies report discrepant results, many authorities prioritize the findings from the randomized clinical trials because those results are less prone to being confounded by unrecognized factors. Randomized trials do not demonstrate that mild SCH or isolated hypothyroxinemia have a major impact on pregnancy outcomes.

Thyroid antibodies, fertility, miscarriage, and preterm birth

Some observational studies report that the presence of thyroid antibodies in a euthyroid woman reduces fecundity and increases the risk for miscarriage and preterm birth. For example, a meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with and without antithyroid antibodies was 6.9% and 4.9%, respectively (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.56). However, in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, low-dose thyroxine therapy has not been shown to improve fertility, or reduce miscarriages or preterm birth rate.

Continue to: In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women...

In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women (normal TSH level; range, 0.44 to 3.63 mIU/L and free thyroxine level; range, 10 to 21 pmol/L) who were planning on conceiving and had elevated thyroid peroxidase antibodies were randomized prior to conception to receive either thyroxine (50 µg) or placebo.7 After 12 months, outcomes were similar for women treated with thyroxine or placebo, including live birth rate (37.4% vs 37.9%), miscarriage rate for those who became pregnant (28.2% vs 29.6%), and preterm birth ≤ 34 weeks of gestation (3.8% vs 3.6%, respectively).7 The investigators concluded that the use of low-dose thyroxine in euthyroid women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies was not effective for increasing the rate of live birth or reducing the rate of miscarriage or early preterm birth.

Thyroid antibodies and the rate of IVF pregnancy and miscarriage

Some observational studies suggest that the presence of antithyroid antibodies may be associated with an increased rate of miscarriage.8 To test the effects of thyroxine treatment on the rate of miscarriage in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, 600 euthyroid infertile women with antithyroid antibodies (antithyroid peroxidase levels ≥ 60 IU/mL) scheduled to have in vitro fertilization (IVF) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (dose adjustment to keep TSH levels in the range of 0.1 to 2.5 mIU/L) or no treatment.9 The thyroxine treatment was initiated 2 to 4 weeks before initiation of ovarian stimulation. In this study, treatment with thyroxine or no treatment resulted in similar rates of clinical pregnancy (35.7% vs 37.7%) and live birth (31.7% vs 32.3%).9 Among the women who achieved a clinical pregnancy, miscarriage rates were similar in the thyroxine and no treatment groups (10.3% vs 10.6%).9

Let’s focus on more serious problems that affect pregnancy

There is a clear consensus that women with overt hypothyroidism should be treated with thyroxine prior to attempting pregnancy.2,6 There is no clear consensus about how to treat women considering pregnancy who have one isolated laboratory finding, such as mild subclinical hypothyroidism, mild isolated hypothyroxinemia, or antithyroid antibodies. Given the lack of evidence from randomized trials that thyroxine improves pregnancy outcomes in these cases, obstetrician-gynecologists may want to either refer women with these problems to an endocrinologist for consultation or sequentially measure laboratory values to assess whether the patient’s laboratory abnormality is transient, stable, or worsening.

Obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients are confronted by many serious problems that adversely affect pregnancy and deserve priority attention, including iron deficiency anemia, excess gestational weight gain, peripartum depression, intimate partner violence, housing insecurity, cigarette smoking, substance misuse, chronic hypertension, morbid obesity, diabetes, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, venous thromboembolism, obstetrical hemorrhage, sepsis, and infectious diseases. Given limited resources our expertise should be focused on these major obstetric public health problems rather than screening for mild subclinical hypothyroidism.

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

- Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

- Abalovich M, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, et al. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Thyroid. 2012;12:63-68.

- Consortium on Thyroid and Pregnancy--Study Group on Preterm Birth. Association of thyroid function test abnormalities and thyroid autoimmunity with preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2019;322:632-641.

- Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, et al. Antenatal thyroid screening and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:493-501.

- Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825.

- Dhillon-Smith RK, Middleton LJ, Sunner KK, et al. Levothyroxine in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1316-1325.

- Chen L, Hu R. Thyroid autoimmunity and miscarriage: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74:513-519.

- Wang H, Gao H, Chi H, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on miscarriage among women with normal thyroid function and thyroid autoimmunity undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2190-2198.

In a US study of more than 17,000 people, overt hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were detected in about 4.6% and 1.3% of adults, respectively.1 In this population-based study, thyroid disease was 5 times more prevalent among women than among men. In our ObGyn practices, there are many women of reproductive age with thyroid disease who are considering pregnancy. Treatment of active hyperthyroidism in a woman planning pregnancy is complex and best managed by endocrinologists. Treatment of hypothyroidism is more straightforward, however, and typically managed by internists, family medicine clinicians, and obstetrician-gynecologists.

Clinical management of hypothyroidism and pregnancy

Pregnancy results in a doubling of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) levels and a 40% increase in plasma volume, resulting in a need for more thyroxine production.2 Of note, from conception to approximately 13 weeks’ gestation, the sole source of embryonic and fetal thyroid hormones is from the mother.2 Women who have been taking chronic thyroxine treatment may have suppressed thyroid gland activity and be unable to increase thyroxine production in response to pregnancy, necessitating a 30% to 50% increase in their thyroxine dose to maintain TSH levels in the normal range.

For hypothyroid women on long-term thyroxine treatment, recommend increasing the thyroxine dose when pregnancy is recognized. For your patients on chronic thyroxine treatment who are planning a pregnancy, a multiprong approach is helpful in preparing the patient for the increased thyroxine requirements of early pregnancy. First, it is important to counsel the woman that she should not stop the thyroxine medication because it may adversely affect the pregnancy. In my experience, most cases of overt hypothyroidism during pregnancy occur because the patient stopped taking her thyroxine therapy. Second, for hypothyroid women who are considering conception it is reasonable to adjust the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration in the lower range of normal (0.5 to 2.5 mU/L). This will give the woman a “buffer,” reducing the risk that in early pregnancy she and her fetus will have a thyroxine deficit. Third, in early pregnancy, following detection of a positive pregnancy test, your patient can start to increase her thyroxine dose by about two tablets weekly (a 28% increase in the dose). Fourth, TSH levels can be measured every 4 weeks during the first trimester, with appropriate adjustment of the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration below the trimester-specific upper limit of normal (< 4 mU/L).2

TSH and free thyroxine measurements identify women with overt hypothyroidism who need thyroxine treatment. Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, including decreased fertility, increased spontaneous abortion, increased fetal loss, and preterm birth.2,3 Hence it is important to immediately initiate thyroxine treatment in pregnant women who have overt hypothyroidism. A diagnosis of overt hypothyroidism is indicated in women with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary axis and a TSH level ≥10 mU/L plus a low free thyroxine concentration. A TSH level of >4 to 10 mU/L, with normal free thyroxine concentration, is evidence of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH). Among women, there are about 5 times more cases of SCH than overt hypothyroidism.

Continue to: The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy...

The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy is vast, and often contradictory, leading to confusion among clinicians. Contributing to the confusion is that some observational studies report a modest association between SCH and adverse pregnancy outcomes. To date, however, randomized clinical trials show no benefit of thyroxine treatment in these cases. I explore these contradictory pieces of evidence below.

Is SCH associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes due to low thyroxine levels?

There is conflicting literature about the association of SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes. A meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with SCH and euthyroid women (normal TSH and normal free thyroxine levels) was 6.1% and 5.0%, respectively (odds ratio [OR], 1.29; 95% CI, 1.01–1.64).4 Interestingly, pregnant women with normal TSH levels but a low free thyroxine level also had an increased rate of preterm birth (7.1% vs 5.0%; OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.12–1.90).

Although observational studies report an association between SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes, multiple randomized clinical trials conducted in women with SCH or hypothyroxinemia have failed to demonstrate that thyroxine replacement improves reproductive outcomes. For example, in a study of 794 pregnant women with elevated TSH and/or low free thyroxine levels randomly assigned to thyroxine treatment (0.15 mg daily) or no treatment, there was no difference in preterm birth rate (5.6% vs 7.9%, P = .2), mean birth weight (3.5 kg vs 3.3 kg, P = .15), gestational age at delivery (40.1 vs 40.2 weeks, P = .10), or the intelligence quotient of children at 3 years (99 vs 100, P = .40).5

In another study, 674 pregnant women with mild SCH (mean TSH, 4.4 mU/L) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (0.1 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal TSH level) or placebo. In this study there was no difference between the thyroxine treatment or placebo groups in preterm birth rate (9% vs 11%, P = .44), gestational age at delivery (39.1 vs 38.9 weeks, P = .57) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (97 and 94, P = .71).6

The same investigators also randomized 524 pregnant women with isolated hypothyroxinema (mean free thyroxine level, 0.83 ng/dL) and normal TSH level (mean, 1.5 mU/L) to thyroxine (0.05 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal free thyroxine level) or placebo.6 In this study there was no difference in preterm birth rate (12% vs 8%, P = .11), gestational age at delivery (39.0 vs 38.8 weeks, P = .46) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (94 and 91, P = .31).6

When large randomized clinical trials and observational studies report discrepant results, many authorities prioritize the findings from the randomized clinical trials because those results are less prone to being confounded by unrecognized factors. Randomized trials do not demonstrate that mild SCH or isolated hypothyroxinemia have a major impact on pregnancy outcomes.

Thyroid antibodies, fertility, miscarriage, and preterm birth

Some observational studies report that the presence of thyroid antibodies in a euthyroid woman reduces fecundity and increases the risk for miscarriage and preterm birth. For example, a meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with and without antithyroid antibodies was 6.9% and 4.9%, respectively (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.56). However, in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, low-dose thyroxine therapy has not been shown to improve fertility, or reduce miscarriages or preterm birth rate.

Continue to: In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women...

In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women (normal TSH level; range, 0.44 to 3.63 mIU/L and free thyroxine level; range, 10 to 21 pmol/L) who were planning on conceiving and had elevated thyroid peroxidase antibodies were randomized prior to conception to receive either thyroxine (50 µg) or placebo.7 After 12 months, outcomes were similar for women treated with thyroxine or placebo, including live birth rate (37.4% vs 37.9%), miscarriage rate for those who became pregnant (28.2% vs 29.6%), and preterm birth ≤ 34 weeks of gestation (3.8% vs 3.6%, respectively).7 The investigators concluded that the use of low-dose thyroxine in euthyroid women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies was not effective for increasing the rate of live birth or reducing the rate of miscarriage or early preterm birth.

Thyroid antibodies and the rate of IVF pregnancy and miscarriage

Some observational studies suggest that the presence of antithyroid antibodies may be associated with an increased rate of miscarriage.8 To test the effects of thyroxine treatment on the rate of miscarriage in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, 600 euthyroid infertile women with antithyroid antibodies (antithyroid peroxidase levels ≥ 60 IU/mL) scheduled to have in vitro fertilization (IVF) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (dose adjustment to keep TSH levels in the range of 0.1 to 2.5 mIU/L) or no treatment.9 The thyroxine treatment was initiated 2 to 4 weeks before initiation of ovarian stimulation. In this study, treatment with thyroxine or no treatment resulted in similar rates of clinical pregnancy (35.7% vs 37.7%) and live birth (31.7% vs 32.3%).9 Among the women who achieved a clinical pregnancy, miscarriage rates were similar in the thyroxine and no treatment groups (10.3% vs 10.6%).9

Let’s focus on more serious problems that affect pregnancy

There is a clear consensus that women with overt hypothyroidism should be treated with thyroxine prior to attempting pregnancy.2,6 There is no clear consensus about how to treat women considering pregnancy who have one isolated laboratory finding, such as mild subclinical hypothyroidism, mild isolated hypothyroxinemia, or antithyroid antibodies. Given the lack of evidence from randomized trials that thyroxine improves pregnancy outcomes in these cases, obstetrician-gynecologists may want to either refer women with these problems to an endocrinologist for consultation or sequentially measure laboratory values to assess whether the patient’s laboratory abnormality is transient, stable, or worsening.

Obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients are confronted by many serious problems that adversely affect pregnancy and deserve priority attention, including iron deficiency anemia, excess gestational weight gain, peripartum depression, intimate partner violence, housing insecurity, cigarette smoking, substance misuse, chronic hypertension, morbid obesity, diabetes, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, venous thromboembolism, obstetrical hemorrhage, sepsis, and infectious diseases. Given limited resources our expertise should be focused on these major obstetric public health problems rather than screening for mild subclinical hypothyroidism.

In a US study of more than 17,000 people, overt hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism were detected in about 4.6% and 1.3% of adults, respectively.1 In this population-based study, thyroid disease was 5 times more prevalent among women than among men. In our ObGyn practices, there are many women of reproductive age with thyroid disease who are considering pregnancy. Treatment of active hyperthyroidism in a woman planning pregnancy is complex and best managed by endocrinologists. Treatment of hypothyroidism is more straightforward, however, and typically managed by internists, family medicine clinicians, and obstetrician-gynecologists.

Clinical management of hypothyroidism and pregnancy

Pregnancy results in a doubling of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) levels and a 40% increase in plasma volume, resulting in a need for more thyroxine production.2 Of note, from conception to approximately 13 weeks’ gestation, the sole source of embryonic and fetal thyroid hormones is from the mother.2 Women who have been taking chronic thyroxine treatment may have suppressed thyroid gland activity and be unable to increase thyroxine production in response to pregnancy, necessitating a 30% to 50% increase in their thyroxine dose to maintain TSH levels in the normal range.

For hypothyroid women on long-term thyroxine treatment, recommend increasing the thyroxine dose when pregnancy is recognized. For your patients on chronic thyroxine treatment who are planning a pregnancy, a multiprong approach is helpful in preparing the patient for the increased thyroxine requirements of early pregnancy. First, it is important to counsel the woman that she should not stop the thyroxine medication because it may adversely affect the pregnancy. In my experience, most cases of overt hypothyroidism during pregnancy occur because the patient stopped taking her thyroxine therapy. Second, for hypothyroid women who are considering conception it is reasonable to adjust the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration in the lower range of normal (0.5 to 2.5 mU/L). This will give the woman a “buffer,” reducing the risk that in early pregnancy she and her fetus will have a thyroxine deficit. Third, in early pregnancy, following detection of a positive pregnancy test, your patient can start to increase her thyroxine dose by about two tablets weekly (a 28% increase in the dose). Fourth, TSH levels can be measured every 4 weeks during the first trimester, with appropriate adjustment of the thyroxine dose to keep the TSH concentration below the trimester-specific upper limit of normal (< 4 mU/L).2

TSH and free thyroxine measurements identify women with overt hypothyroidism who need thyroxine treatment. Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, including decreased fertility, increased spontaneous abortion, increased fetal loss, and preterm birth.2,3 Hence it is important to immediately initiate thyroxine treatment in pregnant women who have overt hypothyroidism. A diagnosis of overt hypothyroidism is indicated in women with an intact hypothalamic-pituitary axis and a TSH level ≥10 mU/L plus a low free thyroxine concentration. A TSH level of >4 to 10 mU/L, with normal free thyroxine concentration, is evidence of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH). Among women, there are about 5 times more cases of SCH than overt hypothyroidism.

Continue to: The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy...

The literature concerning SCH and pregnancy is vast, and often contradictory, leading to confusion among clinicians. Contributing to the confusion is that some observational studies report a modest association between SCH and adverse pregnancy outcomes. To date, however, randomized clinical trials show no benefit of thyroxine treatment in these cases. I explore these contradictory pieces of evidence below.

Is SCH associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes due to low thyroxine levels?

There is conflicting literature about the association of SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes. A meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with SCH and euthyroid women (normal TSH and normal free thyroxine levels) was 6.1% and 5.0%, respectively (odds ratio [OR], 1.29; 95% CI, 1.01–1.64).4 Interestingly, pregnant women with normal TSH levels but a low free thyroxine level also had an increased rate of preterm birth (7.1% vs 5.0%; OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.12–1.90).

Although observational studies report an association between SCH and adverse reproductive outcomes, multiple randomized clinical trials conducted in women with SCH or hypothyroxinemia have failed to demonstrate that thyroxine replacement improves reproductive outcomes. For example, in a study of 794 pregnant women with elevated TSH and/or low free thyroxine levels randomly assigned to thyroxine treatment (0.15 mg daily) or no treatment, there was no difference in preterm birth rate (5.6% vs 7.9%, P = .2), mean birth weight (3.5 kg vs 3.3 kg, P = .15), gestational age at delivery (40.1 vs 40.2 weeks, P = .10), or the intelligence quotient of children at 3 years (99 vs 100, P = .40).5

In another study, 674 pregnant women with mild SCH (mean TSH, 4.4 mU/L) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (0.1 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal TSH level) or placebo. In this study there was no difference between the thyroxine treatment or placebo groups in preterm birth rate (9% vs 11%, P = .44), gestational age at delivery (39.1 vs 38.9 weeks, P = .57) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (97 and 94, P = .71).6

The same investigators also randomized 524 pregnant women with isolated hypothyroxinema (mean free thyroxine level, 0.83 ng/dL) and normal TSH level (mean, 1.5 mU/L) to thyroxine (0.05 mg daily and dose adjusted to achieve a normal free thyroxine level) or placebo.6 In this study there was no difference in preterm birth rate (12% vs 8%, P = .11), gestational age at delivery (39.0 vs 38.8 weeks, P = .46) or intelligence quotient of children at 5 years (94 and 91, P = .31).6

When large randomized clinical trials and observational studies report discrepant results, many authorities prioritize the findings from the randomized clinical trials because those results are less prone to being confounded by unrecognized factors. Randomized trials do not demonstrate that mild SCH or isolated hypothyroxinemia have a major impact on pregnancy outcomes.

Thyroid antibodies, fertility, miscarriage, and preterm birth

Some observational studies report that the presence of thyroid antibodies in a euthyroid woman reduces fecundity and increases the risk for miscarriage and preterm birth. For example, a meta-analysis of 47,045 pregnant women reported that the preterm birth rate for women with and without antithyroid antibodies was 6.9% and 4.9%, respectively (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15–1.56). However, in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, low-dose thyroxine therapy has not been shown to improve fertility, or reduce miscarriages or preterm birth rate.

Continue to: In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women...

In a large randomized clinical trial, 952 euthyroid women (normal TSH level; range, 0.44 to 3.63 mIU/L and free thyroxine level; range, 10 to 21 pmol/L) who were planning on conceiving and had elevated thyroid peroxidase antibodies were randomized prior to conception to receive either thyroxine (50 µg) or placebo.7 After 12 months, outcomes were similar for women treated with thyroxine or placebo, including live birth rate (37.4% vs 37.9%), miscarriage rate for those who became pregnant (28.2% vs 29.6%), and preterm birth ≤ 34 weeks of gestation (3.8% vs 3.6%, respectively).7 The investigators concluded that the use of low-dose thyroxine in euthyroid women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies was not effective for increasing the rate of live birth or reducing the rate of miscarriage or early preterm birth.

Thyroid antibodies and the rate of IVF pregnancy and miscarriage

Some observational studies suggest that the presence of antithyroid antibodies may be associated with an increased rate of miscarriage.8 To test the effects of thyroxine treatment on the rate of miscarriage in euthyroid women with antithyroid antibodies, 600 euthyroid infertile women with antithyroid antibodies (antithyroid peroxidase levels ≥ 60 IU/mL) scheduled to have in vitro fertilization (IVF) were randomly assigned to receive thyroxine (dose adjustment to keep TSH levels in the range of 0.1 to 2.5 mIU/L) or no treatment.9 The thyroxine treatment was initiated 2 to 4 weeks before initiation of ovarian stimulation. In this study, treatment with thyroxine or no treatment resulted in similar rates of clinical pregnancy (35.7% vs 37.7%) and live birth (31.7% vs 32.3%).9 Among the women who achieved a clinical pregnancy, miscarriage rates were similar in the thyroxine and no treatment groups (10.3% vs 10.6%).9

Let’s focus on more serious problems that affect pregnancy

There is a clear consensus that women with overt hypothyroidism should be treated with thyroxine prior to attempting pregnancy.2,6 There is no clear consensus about how to treat women considering pregnancy who have one isolated laboratory finding, such as mild subclinical hypothyroidism, mild isolated hypothyroxinemia, or antithyroid antibodies. Given the lack of evidence from randomized trials that thyroxine improves pregnancy outcomes in these cases, obstetrician-gynecologists may want to either refer women with these problems to an endocrinologist for consultation or sequentially measure laboratory values to assess whether the patient’s laboratory abnormality is transient, stable, or worsening.

Obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients are confronted by many serious problems that adversely affect pregnancy and deserve priority attention, including iron deficiency anemia, excess gestational weight gain, peripartum depression, intimate partner violence, housing insecurity, cigarette smoking, substance misuse, chronic hypertension, morbid obesity, diabetes, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, venous thromboembolism, obstetrical hemorrhage, sepsis, and infectious diseases. Given limited resources our expertise should be focused on these major obstetric public health problems rather than screening for mild subclinical hypothyroidism.

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

- Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

- Abalovich M, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, et al. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Thyroid. 2012;12:63-68.

- Consortium on Thyroid and Pregnancy--Study Group on Preterm Birth. Association of thyroid function test abnormalities and thyroid autoimmunity with preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2019;322:632-641.

- Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, et al. Antenatal thyroid screening and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:493-501.

- Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825.

- Dhillon-Smith RK, Middleton LJ, Sunner KK, et al. Levothyroxine in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1316-1325.

- Chen L, Hu R. Thyroid autoimmunity and miscarriage: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74:513-519.

- Wang H, Gao H, Chi H, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on miscarriage among women with normal thyroid function and thyroid autoimmunity undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2190-2198.

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

- Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

- Abalovich M, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, et al. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Thyroid. 2012;12:63-68.

- Consortium on Thyroid and Pregnancy--Study Group on Preterm Birth. Association of thyroid function test abnormalities and thyroid autoimmunity with preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2019;322:632-641.

- Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, et al. Antenatal thyroid screening and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:493-501.

- Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825.

- Dhillon-Smith RK, Middleton LJ, Sunner KK, et al. Levothyroxine in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1316-1325.

- Chen L, Hu R. Thyroid autoimmunity and miscarriage: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74:513-519.

- Wang H, Gao H, Chi H, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on miscarriage among women with normal thyroid function and thyroid autoimmunity undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2190-2198.

FDA approves diroximel fumarate for relapsing MS

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index predicts long-term outcomes in PAD

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Investigators Use ARMSS Score to Predict Future MS-related Disability

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Smoking Impairs Cognition and Shrinks Brain Volume in MS

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Adolescent Lung Inflammation May Trigger Later MS

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

EHR prompt significantly reduced telemetry monitoring during inpatient stays

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Pink Polycyclic Ulcerations on the Lower Back and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

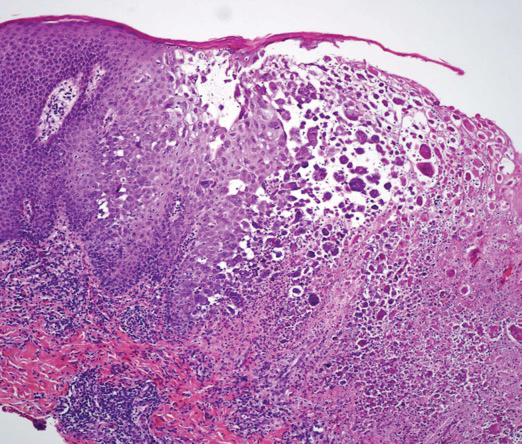

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

A 32-year-old woman with stage IV cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was admitted with pancytopenia and septic shock secondary to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Dermatology was consulted regarding sacral ulcerations. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been slowly enlarging over the course of 1 month. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, pink, polycyclic ulcerations on the lower back and buttocks extending onto the perineum. There was no pain or tingling associated with the ulcerations. She denied a history of cold sore lesions on the lips or genitals. A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and histopathologic examination.

CBT and antidepressants have similar costs for major depressive disorder

according to a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“In the absence of clear superiority of either treatment, shared decision making incorporating patient preferences is critical,” Eric L. Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Ross and colleagues created a decision-analytic model for adults with major depressive disorder in the United States using age and gender data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, and simulated a cohort consisting of 62.2% women with a mean age of 40.7 years. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or received a second-generation antidepressant (SGA) as first-line therapy, and the model calculated risks and benefits of each therapy as well as likelihood of remission and response using data from meta-analyses.

The researchers calculated the average quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of both treatments at 1 years and 5 years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was set at $100,000 or less per QALY for cost effectiveness, and the results were adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars. Researchers also calculated the net monetary benefit of each treatment based on health and economic outcomes.

At 1 year, Dr. Ross and colleagues found quality-adjusted survival in patients who received CBT increased by 3 days (QALY, 0.008; 95% confidence interval, 0.013-0.025) compared with SGA, but there was a higher mean cost to the health care sector ($900; 95% CI, $500-$1,400) and to society ($1,500; 95% CI, $500-$2,500). CBT was not cost effective at 1 year, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in the health care sector of $119,000 per QALY and $186,000 per QALY to society, but the net monetary benefit confidence intervals in the health care sector ($2,400-$1,600) and in society ($3,400-$1,600) appear to show some cost effectiveness for CBT at 1 year, the researchers said.

Compared with SGA, there was an increase of 20 quality-adjusted life days in patients who received CBT at 5 years (QALY, 0.055; 95% CI, 0.044-0.160), and the cost for CBT treatment was reduced by $2,000. While CBT appeared to be cost saving in the base-case analysis, the researchers said there was some uncertainty in the cost effectiveness of CBT when they calculated the incremental net monetary benefit of CBT for the health care sector ($8,100-$21,700) and to society ($10,400-$25,300). In a sensitivity analysis, preference for SGA as a first-line therapy at 1 year was between 64% and 77%, while CBT became more preferred between 1.5 and 2 years, and had between a 73% and 87% preference range at 5 years.

In a related editorial, Mark Sinyor, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, said that although more longitudinal data are needed comparing outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder undergoing treatment with psychotherapy or medication, clinicians should act on what the current evidence shows about the effectiveness of CBT and SGA.

“It is increasingly evident that differences in effectiveness between CBT and SGAs are not substantial and that CBT has some advantages, including potentially lower long-term costs. These must be balanced with the advantages of SGAs, such as potentially more rapid action as well as efficacy across the full [major depressive disorder] severity spectrum,” he said.

Dr. Sinyor also called for CBT and SGA to be made available to all patients with major depressive disorder.

“Antidepressants for [major depressive disorder] are widely accessible in developed countries and that is important for our patients. If we are serious about providing evidence-based care, CBT must become equally available,” he said.

Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health, echoed the sentiment that CBT should be offered alongside antidepressants for treatment of major depressive disorder.

“CBT works as well or better than antidepressant medication, and since people learn skills that they can continue to use, it often has a long-lasting effect. In my experience, for people for whom CBT works – that is, for people who are seeing a therapist who use CBT as their technique and who are willing to put in the work it takes – CBT can be life changing,” he said in an interview. “So, I am not surprised, but I am happy to see the results of this study showing that CBT is cost effective.”

Dr. Skolnik emphasized that not every therapist offers CBT, so health care providers should be aware of the type of therapy they are referring their patients for and monitor that therapy when possible.

“We should talk to our patients, present them with options, and then decide together with our patients which approach is best for them,” Dr. Skolnik added. “Medications work, and for many this is a good choice. CBT works, and for many this is a good choice. For some patients, using both CBT and medications is the optimal choice. Both are about equally cost effective. We should discuss the options with our patients and decide the path forward together.”

This study was funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Ross reported receiving a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Two coauthors reported receiving grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Sinyor and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ross EL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-1480.

according to a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“In the absence of clear superiority of either treatment, shared decision making incorporating patient preferences is critical,” Eric L. Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Ross and colleagues created a decision-analytic model for adults with major depressive disorder in the United States using age and gender data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, and simulated a cohort consisting of 62.2% women with a mean age of 40.7 years. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or received a second-generation antidepressant (SGA) as first-line therapy, and the model calculated risks and benefits of each therapy as well as likelihood of remission and response using data from meta-analyses.

The researchers calculated the average quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of both treatments at 1 years and 5 years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was set at $100,000 or less per QALY for cost effectiveness, and the results were adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars. Researchers also calculated the net monetary benefit of each treatment based on health and economic outcomes.

At 1 year, Dr. Ross and colleagues found quality-adjusted survival in patients who received CBT increased by 3 days (QALY, 0.008; 95% confidence interval, 0.013-0.025) compared with SGA, but there was a higher mean cost to the health care sector ($900; 95% CI, $500-$1,400) and to society ($1,500; 95% CI, $500-$2,500). CBT was not cost effective at 1 year, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in the health care sector of $119,000 per QALY and $186,000 per QALY to society, but the net monetary benefit confidence intervals in the health care sector ($2,400-$1,600) and in society ($3,400-$1,600) appear to show some cost effectiveness for CBT at 1 year, the researchers said.

Compared with SGA, there was an increase of 20 quality-adjusted life days in patients who received CBT at 5 years (QALY, 0.055; 95% CI, 0.044-0.160), and the cost for CBT treatment was reduced by $2,000. While CBT appeared to be cost saving in the base-case analysis, the researchers said there was some uncertainty in the cost effectiveness of CBT when they calculated the incremental net monetary benefit of CBT for the health care sector ($8,100-$21,700) and to society ($10,400-$25,300). In a sensitivity analysis, preference for SGA as a first-line therapy at 1 year was between 64% and 77%, while CBT became more preferred between 1.5 and 2 years, and had between a 73% and 87% preference range at 5 years.

In a related editorial, Mark Sinyor, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, said that although more longitudinal data are needed comparing outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder undergoing treatment with psychotherapy or medication, clinicians should act on what the current evidence shows about the effectiveness of CBT and SGA.

“It is increasingly evident that differences in effectiveness between CBT and SGAs are not substantial and that CBT has some advantages, including potentially lower long-term costs. These must be balanced with the advantages of SGAs, such as potentially more rapid action as well as efficacy across the full [major depressive disorder] severity spectrum,” he said.

Dr. Sinyor also called for CBT and SGA to be made available to all patients with major depressive disorder.

“Antidepressants for [major depressive disorder] are widely accessible in developed countries and that is important for our patients. If we are serious about providing evidence-based care, CBT must become equally available,” he said.

Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health, echoed the sentiment that CBT should be offered alongside antidepressants for treatment of major depressive disorder.

“CBT works as well or better than antidepressant medication, and since people learn skills that they can continue to use, it often has a long-lasting effect. In my experience, for people for whom CBT works – that is, for people who are seeing a therapist who use CBT as their technique and who are willing to put in the work it takes – CBT can be life changing,” he said in an interview. “So, I am not surprised, but I am happy to see the results of this study showing that CBT is cost effective.”

Dr. Skolnik emphasized that not every therapist offers CBT, so health care providers should be aware of the type of therapy they are referring their patients for and monitor that therapy when possible.