User login

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Clostridium difficile Infections in Children

Clostridium difficile (name changed to Clostridioides difficile [CDI]) are a major public health problem, with 500,000 infections annually in the United States, 15,000-30,000 associated deaths, and acute care costs exceeding $4.8 billion. The recent clinical practice guideline for CDI provides recommendations about the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and environmental management. A total of 52 recommendations are included, and we will review 11 with pertinence to pediatrics in this highlight.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. In infants ≤12 months of age, testing for CDI should never be routinely recommended because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic carriage of toxigenic C. difficile in infants (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 2. In children 1-2 years of age, testing should not be routinely performed unless other causes have been excluded (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).Recommendation 3. In children ≥2 years of age, testing is recommended for patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and risk factors (eg, underlying inflammatory bowel disease) or immunocompromising conditions) or relevant exposures (eg, contact with the healthcare system or recent antibiotics) (weak recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

The rate of C. difficile colonization among asymptomatic infants can exceed 40%. This rate declines over the first year but remains 15% at 12 months of age.1 Therefore, the guideline recommends against routinely testing infants ≤12 months of age as a positive test probably reflects colonization rather than disease. Testing in infants is recommended only when other causes have been excluded and a concern for pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, or clinically significant diarrhea exists.

The rate of asymptomatic colonization remains elevated in the second year of life. By 2-3 years, the rate is 1%-3% which is similar to that in healthy adults. However, the role of C. difficile in community-onset diarrhea in otherwise healthy children is controversial. In a study of 100 hospitalized children aged <2 years with CDI and diarrhea, all had resolution of diarrhea regardless of whether therapy was administered.2 Another study found an alternative pathogen in >50% of hospitalized children with CDI.3 Therefore, the guideline recommends against testing in children aged 1-2 years unless other causes have been excluded and in children aged >2 years only when they have prolonged or worsening diarrhea along with risk factors or exposures.

Recommendation 4. In institutions without specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a stool toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm (ie, glutamate dehydrogenase [GDH] plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by nucleic-acid amplification tests [NAAT], or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a NAAT alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Recommendation 5. In institutions with specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm for testing (ie, GDH plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by NAAT, or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a toxin test alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There are a variety of testing approaches for CDI and recommendations vary based on local practice. If laboratories accept all stools, a more specific approach is recommended, including a toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm to limit false positives. If laboratories first screen for symptoms and antibiotic exposure before accepting stool samples, a more sensitive approach is recommended including NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm rather than toxin alone.

Infection Prevention and Control

Recommendation 6. There is insufficient evidence for discontinuation of PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) as a measure for preventing CDI (no recommendation).

The guideline acknowledges data suggesting an association between PPI use and CDI, but not a causal relationship. Due to the lack of high-quality evidence, it does not recommend stopping PPIs to prevent CDI.

Recommendation 7. There are insufficient data to recommend probiotics for primary prevention of CDI outside of clinical trials (no recommendation).

The guideline notes that although several meta-analyses indicate that probiotics may prevent CDI; however there were limitations, including a high incidence of CDI in placebo arms and differences in probiotic formulations and duration of use, leading to insufficient data to recommend probiotic use to prevent CDI.

Treatment

Recommendation 8. Either per os (PO) metronidazole or PO vancomycin is recommended for an initial episode or first recurrence of nonsevere pediatric CDI (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Data assessing the optimal treatment for nonsevere pediatric CDI are limited. Emerging data support the use of vancomycin,4 which is now recommended for initial episodes of CDI in adults. However, there are insufficient data to recommend vancomycin over metronidazole for nonsevere pediatric CDI; therefore, either option is recommended.

Recommendation 9. For children with an initial episode of severe CDI, oral vancomycin with or without IV metronidazole is recommended over metronidazole alone (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 10. For children with a second or greater episode of recurrent CDI, oral vancomycin is recommended over metronidazole (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There is no well-designed trial comparing metronidazole and vancomycin for severe or recurrent pediatric CDI. For children previously treated with metronidazole, vancomycin is recommended based on adult literature.4 For children previously treated with metronidazole and vancomycin, an extended course of tapered or pulse regimen vancomycin or vancomycin followed by rifaximin is recommended.

Recommendations must weigh potential harms. Metronidazole has been associated with neuropathies,5 cramping, and nausea. PO vancomycin has poor enteral absorption, minimizing systemic effects. Both vancomycin and metronidazole may promote carriage of resistant enterococci.

Recommendation 11. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) should be considered for pediatric patients with multiple recurrences of CDI following standard treatments (weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence).

There are no robust data examining the effectiveness of pediatric FMT. Recommendations are guided by adult studies. Limited evidence suggests that FMT can be effective in children with multiple recurrent CDI.6 Concerns include procedure-related risks, transmission of resistant organisms and blood-borne pathogens, and induced metabolic or immunologic disorders.

CRITIQUE

Methods in Preparing a Guideline

The strength of a guideline includes representation from a diverse panel, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists, the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The panel utilized the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system to weigh the strength and quality of evidence.

From a pediatric perspective, the current guideline added pediatric-specific recommendations based on a comprehensive review of the literature from 1977 to 2016. The strength of these recommendations is somewhat limited by the lack of well-designed pediatric studies. An additional limitation is that treatment recommendations are based on illness severity, although the definitions used to classify severity are not pediatric-specific and are based on unvalidated expert opinion.

Sources of Potential Conflicts or Interest or Bias

The panel complied with the IDSA policy on conflicts of interest and disclosed any interest that might be construed as a conflict, regardless of relevancy. These were evaluated by the IDSA Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee.

Generalizability

Guideline generalizability may be impacted by testing availabilities within a particular setting. Cost factors and local formularies may also limit treatment options within a given setting.

Areas in Need of Future Study

Research gaps exist regarding at what age C. difficile is pathogenic given the prevalence of asymptomatic carriage. Future studies can also focus on a newly available molecular polymerase chain reaction test platform that detects C. difficile.7

There is limited pediatric evidence to recommend metronidazole versus vancomycin in children, particularly in nonsevere cases. There is also an opportunity to further explore alternative therapies, including fidaxomicin (not currently approved for children) and bezlotoxumab, a new agent approved as adult adjunctive therapy.8

1. Donta ST, Myers MG. Clostridium difficile toxin in asymptomatic neonates. J Pediatr. 1982;100(3):431-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80454-x.

2. González-Del Vecchio M, Álvarez-Uria A, Marin M, et al. Clinical significance of Clostridium difficile in children less than 2 years old: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(3):281-285. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001008.

3. Valentini D, Vittucci AC, Grandin A, et al. Coinfection in acute gastroenteritis predicts a more severe clinical course in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(7):909-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1825-9.

4. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu313.

5. Yamamoto T, Abe K, Anjiki H, Ishii T, Kuyama Y. Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity developed in liver cirrhosis. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(4):295-298. https://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr893w.

6. Russell G, Kaplan J, Ferraro M, Michelow IC. Fecal bacteriotherapy for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in a child: a proposed treatment protocol. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e239-e242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3363.

7. Zhang H, Morrison S, Tang YW. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests for detection of pathogens associated with gastroenteritis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(2):461-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2015.02.006.

8. Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1602615.

Clostridium difficile (name changed to Clostridioides difficile [CDI]) are a major public health problem, with 500,000 infections annually in the United States, 15,000-30,000 associated deaths, and acute care costs exceeding $4.8 billion. The recent clinical practice guideline for CDI provides recommendations about the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and environmental management. A total of 52 recommendations are included, and we will review 11 with pertinence to pediatrics in this highlight.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. In infants ≤12 months of age, testing for CDI should never be routinely recommended because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic carriage of toxigenic C. difficile in infants (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 2. In children 1-2 years of age, testing should not be routinely performed unless other causes have been excluded (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).Recommendation 3. In children ≥2 years of age, testing is recommended for patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and risk factors (eg, underlying inflammatory bowel disease) or immunocompromising conditions) or relevant exposures (eg, contact with the healthcare system or recent antibiotics) (weak recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

The rate of C. difficile colonization among asymptomatic infants can exceed 40%. This rate declines over the first year but remains 15% at 12 months of age.1 Therefore, the guideline recommends against routinely testing infants ≤12 months of age as a positive test probably reflects colonization rather than disease. Testing in infants is recommended only when other causes have been excluded and a concern for pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, or clinically significant diarrhea exists.

The rate of asymptomatic colonization remains elevated in the second year of life. By 2-3 years, the rate is 1%-3% which is similar to that in healthy adults. However, the role of C. difficile in community-onset diarrhea in otherwise healthy children is controversial. In a study of 100 hospitalized children aged <2 years with CDI and diarrhea, all had resolution of diarrhea regardless of whether therapy was administered.2 Another study found an alternative pathogen in >50% of hospitalized children with CDI.3 Therefore, the guideline recommends against testing in children aged 1-2 years unless other causes have been excluded and in children aged >2 years only when they have prolonged or worsening diarrhea along with risk factors or exposures.

Recommendation 4. In institutions without specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a stool toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm (ie, glutamate dehydrogenase [GDH] plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by nucleic-acid amplification tests [NAAT], or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a NAAT alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Recommendation 5. In institutions with specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm for testing (ie, GDH plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by NAAT, or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a toxin test alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There are a variety of testing approaches for CDI and recommendations vary based on local practice. If laboratories accept all stools, a more specific approach is recommended, including a toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm to limit false positives. If laboratories first screen for symptoms and antibiotic exposure before accepting stool samples, a more sensitive approach is recommended including NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm rather than toxin alone.

Infection Prevention and Control

Recommendation 6. There is insufficient evidence for discontinuation of PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) as a measure for preventing CDI (no recommendation).

The guideline acknowledges data suggesting an association between PPI use and CDI, but not a causal relationship. Due to the lack of high-quality evidence, it does not recommend stopping PPIs to prevent CDI.

Recommendation 7. There are insufficient data to recommend probiotics for primary prevention of CDI outside of clinical trials (no recommendation).

The guideline notes that although several meta-analyses indicate that probiotics may prevent CDI; however there were limitations, including a high incidence of CDI in placebo arms and differences in probiotic formulations and duration of use, leading to insufficient data to recommend probiotic use to prevent CDI.

Treatment

Recommendation 8. Either per os (PO) metronidazole or PO vancomycin is recommended for an initial episode or first recurrence of nonsevere pediatric CDI (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Data assessing the optimal treatment for nonsevere pediatric CDI are limited. Emerging data support the use of vancomycin,4 which is now recommended for initial episodes of CDI in adults. However, there are insufficient data to recommend vancomycin over metronidazole for nonsevere pediatric CDI; therefore, either option is recommended.

Recommendation 9. For children with an initial episode of severe CDI, oral vancomycin with or without IV metronidazole is recommended over metronidazole alone (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 10. For children with a second or greater episode of recurrent CDI, oral vancomycin is recommended over metronidazole (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There is no well-designed trial comparing metronidazole and vancomycin for severe or recurrent pediatric CDI. For children previously treated with metronidazole, vancomycin is recommended based on adult literature.4 For children previously treated with metronidazole and vancomycin, an extended course of tapered or pulse regimen vancomycin or vancomycin followed by rifaximin is recommended.

Recommendations must weigh potential harms. Metronidazole has been associated with neuropathies,5 cramping, and nausea. PO vancomycin has poor enteral absorption, minimizing systemic effects. Both vancomycin and metronidazole may promote carriage of resistant enterococci.

Recommendation 11. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) should be considered for pediatric patients with multiple recurrences of CDI following standard treatments (weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence).

There are no robust data examining the effectiveness of pediatric FMT. Recommendations are guided by adult studies. Limited evidence suggests that FMT can be effective in children with multiple recurrent CDI.6 Concerns include procedure-related risks, transmission of resistant organisms and blood-borne pathogens, and induced metabolic or immunologic disorders.

CRITIQUE

Methods in Preparing a Guideline

The strength of a guideline includes representation from a diverse panel, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists, the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The panel utilized the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system to weigh the strength and quality of evidence.

From a pediatric perspective, the current guideline added pediatric-specific recommendations based on a comprehensive review of the literature from 1977 to 2016. The strength of these recommendations is somewhat limited by the lack of well-designed pediatric studies. An additional limitation is that treatment recommendations are based on illness severity, although the definitions used to classify severity are not pediatric-specific and are based on unvalidated expert opinion.

Sources of Potential Conflicts or Interest or Bias

The panel complied with the IDSA policy on conflicts of interest and disclosed any interest that might be construed as a conflict, regardless of relevancy. These were evaluated by the IDSA Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee.

Generalizability

Guideline generalizability may be impacted by testing availabilities within a particular setting. Cost factors and local formularies may also limit treatment options within a given setting.

Areas in Need of Future Study

Research gaps exist regarding at what age C. difficile is pathogenic given the prevalence of asymptomatic carriage. Future studies can also focus on a newly available molecular polymerase chain reaction test platform that detects C. difficile.7

There is limited pediatric evidence to recommend metronidazole versus vancomycin in children, particularly in nonsevere cases. There is also an opportunity to further explore alternative therapies, including fidaxomicin (not currently approved for children) and bezlotoxumab, a new agent approved as adult adjunctive therapy.8

Clostridium difficile (name changed to Clostridioides difficile [CDI]) are a major public health problem, with 500,000 infections annually in the United States, 15,000-30,000 associated deaths, and acute care costs exceeding $4.8 billion. The recent clinical practice guideline for CDI provides recommendations about the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and environmental management. A total of 52 recommendations are included, and we will review 11 with pertinence to pediatrics in this highlight.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. In infants ≤12 months of age, testing for CDI should never be routinely recommended because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic carriage of toxigenic C. difficile in infants (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 2. In children 1-2 years of age, testing should not be routinely performed unless other causes have been excluded (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).Recommendation 3. In children ≥2 years of age, testing is recommended for patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and risk factors (eg, underlying inflammatory bowel disease) or immunocompromising conditions) or relevant exposures (eg, contact with the healthcare system or recent antibiotics) (weak recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

The rate of C. difficile colonization among asymptomatic infants can exceed 40%. This rate declines over the first year but remains 15% at 12 months of age.1 Therefore, the guideline recommends against routinely testing infants ≤12 months of age as a positive test probably reflects colonization rather than disease. Testing in infants is recommended only when other causes have been excluded and a concern for pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, or clinically significant diarrhea exists.

The rate of asymptomatic colonization remains elevated in the second year of life. By 2-3 years, the rate is 1%-3% which is similar to that in healthy adults. However, the role of C. difficile in community-onset diarrhea in otherwise healthy children is controversial. In a study of 100 hospitalized children aged <2 years with CDI and diarrhea, all had resolution of diarrhea regardless of whether therapy was administered.2 Another study found an alternative pathogen in >50% of hospitalized children with CDI.3 Therefore, the guideline recommends against testing in children aged 1-2 years unless other causes have been excluded and in children aged >2 years only when they have prolonged or worsening diarrhea along with risk factors or exposures.

Recommendation 4. In institutions without specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a stool toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm (ie, glutamate dehydrogenase [GDH] plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by nucleic-acid amplification tests [NAAT], or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a NAAT alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Recommendation 5. In institutions with specific required criteria for stool submissions, use a NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm for testing (ie, GDH plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by NAAT, or NAAT plus toxin) rather than a toxin test alone (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There are a variety of testing approaches for CDI and recommendations vary based on local practice. If laboratories accept all stools, a more specific approach is recommended, including a toxin test as part of a multistep algorithm to limit false positives. If laboratories first screen for symptoms and antibiotic exposure before accepting stool samples, a more sensitive approach is recommended including NAAT alone or a multistep algorithm rather than toxin alone.

Infection Prevention and Control

Recommendation 6. There is insufficient evidence for discontinuation of PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) as a measure for preventing CDI (no recommendation).

The guideline acknowledges data suggesting an association between PPI use and CDI, but not a causal relationship. Due to the lack of high-quality evidence, it does not recommend stopping PPIs to prevent CDI.

Recommendation 7. There are insufficient data to recommend probiotics for primary prevention of CDI outside of clinical trials (no recommendation).

The guideline notes that although several meta-analyses indicate that probiotics may prevent CDI; however there were limitations, including a high incidence of CDI in placebo arms and differences in probiotic formulations and duration of use, leading to insufficient data to recommend probiotic use to prevent CDI.

Treatment

Recommendation 8. Either per os (PO) metronidazole or PO vancomycin is recommended for an initial episode or first recurrence of nonsevere pediatric CDI (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Data assessing the optimal treatment for nonsevere pediatric CDI are limited. Emerging data support the use of vancomycin,4 which is now recommended for initial episodes of CDI in adults. However, there are insufficient data to recommend vancomycin over metronidazole for nonsevere pediatric CDI; therefore, either option is recommended.

Recommendation 9. For children with an initial episode of severe CDI, oral vancomycin with or without IV metronidazole is recommended over metronidazole alone (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).

Recommendation 10. For children with a second or greater episode of recurrent CDI, oral vancomycin is recommended over metronidazole (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence).

There is no well-designed trial comparing metronidazole and vancomycin for severe or recurrent pediatric CDI. For children previously treated with metronidazole, vancomycin is recommended based on adult literature.4 For children previously treated with metronidazole and vancomycin, an extended course of tapered or pulse regimen vancomycin or vancomycin followed by rifaximin is recommended.

Recommendations must weigh potential harms. Metronidazole has been associated with neuropathies,5 cramping, and nausea. PO vancomycin has poor enteral absorption, minimizing systemic effects. Both vancomycin and metronidazole may promote carriage of resistant enterococci.

Recommendation 11. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) should be considered for pediatric patients with multiple recurrences of CDI following standard treatments (weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence).

There are no robust data examining the effectiveness of pediatric FMT. Recommendations are guided by adult studies. Limited evidence suggests that FMT can be effective in children with multiple recurrent CDI.6 Concerns include procedure-related risks, transmission of resistant organisms and blood-borne pathogens, and induced metabolic or immunologic disorders.

CRITIQUE

Methods in Preparing a Guideline

The strength of a guideline includes representation from a diverse panel, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists, the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The panel utilized the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system to weigh the strength and quality of evidence.

From a pediatric perspective, the current guideline added pediatric-specific recommendations based on a comprehensive review of the literature from 1977 to 2016. The strength of these recommendations is somewhat limited by the lack of well-designed pediatric studies. An additional limitation is that treatment recommendations are based on illness severity, although the definitions used to classify severity are not pediatric-specific and are based on unvalidated expert opinion.

Sources of Potential Conflicts or Interest or Bias

The panel complied with the IDSA policy on conflicts of interest and disclosed any interest that might be construed as a conflict, regardless of relevancy. These were evaluated by the IDSA Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee.

Generalizability

Guideline generalizability may be impacted by testing availabilities within a particular setting. Cost factors and local formularies may also limit treatment options within a given setting.

Areas in Need of Future Study

Research gaps exist regarding at what age C. difficile is pathogenic given the prevalence of asymptomatic carriage. Future studies can also focus on a newly available molecular polymerase chain reaction test platform that detects C. difficile.7

There is limited pediatric evidence to recommend metronidazole versus vancomycin in children, particularly in nonsevere cases. There is also an opportunity to further explore alternative therapies, including fidaxomicin (not currently approved for children) and bezlotoxumab, a new agent approved as adult adjunctive therapy.8

1. Donta ST, Myers MG. Clostridium difficile toxin in asymptomatic neonates. J Pediatr. 1982;100(3):431-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80454-x.

2. González-Del Vecchio M, Álvarez-Uria A, Marin M, et al. Clinical significance of Clostridium difficile in children less than 2 years old: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(3):281-285. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001008.

3. Valentini D, Vittucci AC, Grandin A, et al. Coinfection in acute gastroenteritis predicts a more severe clinical course in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(7):909-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1825-9.

4. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu313.

5. Yamamoto T, Abe K, Anjiki H, Ishii T, Kuyama Y. Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity developed in liver cirrhosis. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(4):295-298. https://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr893w.

6. Russell G, Kaplan J, Ferraro M, Michelow IC. Fecal bacteriotherapy for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in a child: a proposed treatment protocol. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e239-e242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3363.

7. Zhang H, Morrison S, Tang YW. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests for detection of pathogens associated with gastroenteritis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(2):461-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2015.02.006.

8. Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1602615.

1. Donta ST, Myers MG. Clostridium difficile toxin in asymptomatic neonates. J Pediatr. 1982;100(3):431-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80454-x.

2. González-Del Vecchio M, Álvarez-Uria A, Marin M, et al. Clinical significance of Clostridium difficile in children less than 2 years old: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(3):281-285. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001008.

3. Valentini D, Vittucci AC, Grandin A, et al. Coinfection in acute gastroenteritis predicts a more severe clinical course in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(7):909-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1825-9.

4. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu313.

5. Yamamoto T, Abe K, Anjiki H, Ishii T, Kuyama Y. Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity developed in liver cirrhosis. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(4):295-298. https://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr893w.

6. Russell G, Kaplan J, Ferraro M, Michelow IC. Fecal bacteriotherapy for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in a child: a proposed treatment protocol. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e239-e242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3363.

7. Zhang H, Morrison S, Tang YW. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests for detection of pathogens associated with gastroenteritis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(2):461-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2015.02.006.

8. Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1602615.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Call to Action: Hospitalists’ Role in Addressing Substance Use Disorder

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

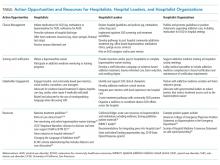

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

1. Weiss A, Elixhauser A, Barrett M, Steiner C, Bailey M, O’Malley L. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009-2014. Statistical Brief #219. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp. Accessed May 21, 2019.

2. Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183758. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3758.

3. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424.

4. Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med. 2012;6(1):50-56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51.

5. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736.

6. Velez C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis P, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. doi 10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4.

7. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z.

8. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993.

9. McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD005191 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3.

10. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496.

11. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001.

12. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010.

13. Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019. pii: S0955-3959(19)30018-0. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010.

14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder-Executive Summary. February 2018. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Executive-Summary/sma18-5063exsumm. Accessed August 8, 2019.

15. Providers Clinical Support System. Discover the rewards of treating patients with Opioid Use Disorders. https://pcssnow.org/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

16. California Bridge Program. Treatment Starts Here: Resources for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders from the Acute Care Setting. https://www.bridgetotreatment.org/resources. Accessed August 7, 2019.

17. Clinical Consultation Center. Substance Use Resources. 2019. https://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/substance-use-resources/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

18. Thakarar K, Weinstein ZM, Walley AY. Optimising health and safety of people who inject drugs during transition from acute to outpatient care: narrative review with clinical checklist. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1088):356-363. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133720.

19. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the Language of Addiction. Washington, D.C. 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.

20. The University of New Mexico. Project ECHO: A Revolution in Medical Education and Care Delivery. 2019. https://echo.unm.edu/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

21. Englander H, Mahoney S, Brandt K, et al. Tools to support hospital-based addiction care: core components, values, and activities of the Improving Addiction Care Team. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):85-89. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000487.

22. Englander H, Gregg J, Gollickson J, et al. Recommendations for intergrating peer mentors in hospital-based addiction care. Subst Abus. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1635968.

23. American College of Medical Toxicology. ACMT Position Statement: Buprenorphine Administration in the Emergency Department. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/equal-documents/policy_acmt_bupeadministration.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2019.

24. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

25. Winetsky D, Weinrieb RM, Perrone J. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):62-64. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2861.

26. Frank JW, Wakeman SE, Gordon AJ. No end to the crisis without an end to the waiver. Subst Abus. 2018;39(3):263-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1543382.

27. Gorfinkel L, Klimas J, Reel B, et al. In-hospital training in addiction medicine: a mixed-methods study of health care provider benefits and differences. Subst Abus. 2019. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1561596.

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

1. Weiss A, Elixhauser A, Barrett M, Steiner C, Bailey M, O’Malley L. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009-2014. Statistical Brief #219. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp. Accessed May 21, 2019.

2. Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183758. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3758.

3. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424.

4. Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med. 2012;6(1):50-56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51.

5. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736.

6. Velez C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis P, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. doi 10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4.

7. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z.

8. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993.

9. McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD005191 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3.

10. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496.

11. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001.

12. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010.

13. Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019. pii: S0955-3959(19)30018-0. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010.

14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder-Executive Summary. February 2018. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Executive-Summary/sma18-5063exsumm. Accessed August 8, 2019.

15. Providers Clinical Support System. Discover the rewards of treating patients with Opioid Use Disorders. https://pcssnow.org/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

16. California Bridge Program. Treatment Starts Here: Resources for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders from the Acute Care Setting. https://www.bridgetotreatment.org/resources. Accessed August 7, 2019.

17. Clinical Consultation Center. Substance Use Resources. 2019. https://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/substance-use-resources/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

18. Thakarar K, Weinstein ZM, Walley AY. Optimising health and safety of people who inject drugs during transition from acute to outpatient care: narrative review with clinical checklist. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1088):356-363. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133720.

19. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the Language of Addiction. Washington, D.C. 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.