User login

FDA approves Trikafta for treatment of cystic fibrosis

in patients aged 12 years or older, the first triple-combination therapy approved for that indication.

Approval for Trikafta was based on results from two clinical trials in patients with cystic fibrosis with an F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. In the first trial, a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 403 patients, the mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second increased by 14% from baseline, compared with placebo. In the second trial, a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study of 107 patients, mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second was increased 10% from baseline, compared with tezacaftor/ivacaftor, according to the FDA press release.

In the first trial, patients who received Trikafta also saw improvement in sweat chloride, reduction in the number of pulmonary exacerbations, and reduction of body mass index, compared with placebo.

The most common adverse events associated with Trikafta during the trials were headaches, upper respiratory tract infections, abdominal pains, diarrhea, rashes, and rhinorrhea, among others. The label includes a warning related to elevated liver function tests, use at the same time with products that induce or inhibit a liver enzyme called cytochrome P450 3A4, and cataract risk.

“At the FDA, we’re consistently looking for ways to help speed the development of new therapies for complex diseases, while maintaining our high standards of review. Today’s landmark approval is a testament to these efforts, making a novel treatment available to most cystic fibrosis patients, including adolescents, who previously had no options and giving others in the cystic fibrosis community access to an additional effective therapy,” said acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

in patients aged 12 years or older, the first triple-combination therapy approved for that indication.

Approval for Trikafta was based on results from two clinical trials in patients with cystic fibrosis with an F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. In the first trial, a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 403 patients, the mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second increased by 14% from baseline, compared with placebo. In the second trial, a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study of 107 patients, mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second was increased 10% from baseline, compared with tezacaftor/ivacaftor, according to the FDA press release.

In the first trial, patients who received Trikafta also saw improvement in sweat chloride, reduction in the number of pulmonary exacerbations, and reduction of body mass index, compared with placebo.

The most common adverse events associated with Trikafta during the trials were headaches, upper respiratory tract infections, abdominal pains, diarrhea, rashes, and rhinorrhea, among others. The label includes a warning related to elevated liver function tests, use at the same time with products that induce or inhibit a liver enzyme called cytochrome P450 3A4, and cataract risk.

“At the FDA, we’re consistently looking for ways to help speed the development of new therapies for complex diseases, while maintaining our high standards of review. Today’s landmark approval is a testament to these efforts, making a novel treatment available to most cystic fibrosis patients, including adolescents, who previously had no options and giving others in the cystic fibrosis community access to an additional effective therapy,” said acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

in patients aged 12 years or older, the first triple-combination therapy approved for that indication.

Approval for Trikafta was based on results from two clinical trials in patients with cystic fibrosis with an F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. In the first trial, a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 403 patients, the mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second increased by 14% from baseline, compared with placebo. In the second trial, a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study of 107 patients, mean percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second was increased 10% from baseline, compared with tezacaftor/ivacaftor, according to the FDA press release.

In the first trial, patients who received Trikafta also saw improvement in sweat chloride, reduction in the number of pulmonary exacerbations, and reduction of body mass index, compared with placebo.

The most common adverse events associated with Trikafta during the trials were headaches, upper respiratory tract infections, abdominal pains, diarrhea, rashes, and rhinorrhea, among others. The label includes a warning related to elevated liver function tests, use at the same time with products that induce or inhibit a liver enzyme called cytochrome P450 3A4, and cataract risk.

“At the FDA, we’re consistently looking for ways to help speed the development of new therapies for complex diseases, while maintaining our high standards of review. Today’s landmark approval is a testament to these efforts, making a novel treatment available to most cystic fibrosis patients, including adolescents, who previously had no options and giving others in the cystic fibrosis community access to an additional effective therapy,” said acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Native Americans appear to be at increased risk for AFib

Over 4 years, atrial fibrillation (AFib) developed significantly more often in a group of Native Americans men than it did among other racial and ethnic groups, a large longitudinal cohort study has found.

The overall incidence among Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the incidence in a comparator cohort of black, white, Asian, and Hispanic men, Gregory M. Marcus, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote in a research letter published in Circulation.

“We were surprised to find that American Indians experienced a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared to every other racial and ethnic group,” Dr. Marcus said in a press release that accompanied the study. “Understanding the mechanisms and factors by which American Indians experience this higher risk may help investigators better understand the fundamental causes of atrial fibrillation that prove useful to everyone at risk for AFib, regardless of their race or ethnicity.”

The team plumbed the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) California state databases for information on more than 16 million cases of AFib that occurred during 2005-2011. Native Americans comprised just 0.6% of the cohort. Most of the patients (57.2%) were white; 8% were black, 25.6% Hispanic, and 8.6% Asian. After targeting only new-onset cases, there were 344,469 incident AFib episodes over a median follow-up of 4.1 years.

The overall incidence of AFib in Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years, significantly higher than the 6.89 per 1000 person-years observed in the rest of the cohort ( P less than .0001). The difference remained significant even after the team controlled for age, sex, income, and heart and other diseases. Nor was it altered by a sensitivity analysis that controlled for place of presentation and patients who were aged at least 35 years with at least two encounters with medical facilities.

In an interaction analysis, the increased risk appeared to be driven by higher rates of diabetes and chronic kidney disease, the authors wrote.

“This may suggest that the presence of these two processes contributes some pathophysiology related to AF[ib] risk that may be similar to the heightened risk inherent among American Indians,” they wrote. “It is also important to note that there was no evidence of any other statistically significant interactions despite the inclusion of millions of patients.”

Supporting data for these associations were not included in the research letter.

The authors noted some limitations of their study. Race or ethnicity were self-reported and could not be independently confirmed, so there was no way to tease out the effects in multiracial patients. Also, the database didn’t record outpatient encounters, which might result in some selection bias.

“Last, because this was an observational study, these results should not be interpreted as evidence of causal effect,” they noted.

“In conclusion, we observed that American Indians had a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared with all other racial and ethnic group. The heightened risk … in American Indians persisted after multivariable adjustment for known conventional confounders and mediators, suggesting that an unidentified characteristic, including possible genetic or environmental factors, may be responsible,” the investigators wrote.

The HCUP database is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Marcus reported receiving research support from Jawbone, Medtronic, Eight, and Baylis Medical, and is a consultant for and holds equity in InCarda Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marcus GM et al. Circulation. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042882.

Over 4 years, atrial fibrillation (AFib) developed significantly more often in a group of Native Americans men than it did among other racial and ethnic groups, a large longitudinal cohort study has found.

The overall incidence among Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the incidence in a comparator cohort of black, white, Asian, and Hispanic men, Gregory M. Marcus, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote in a research letter published in Circulation.

“We were surprised to find that American Indians experienced a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared to every other racial and ethnic group,” Dr. Marcus said in a press release that accompanied the study. “Understanding the mechanisms and factors by which American Indians experience this higher risk may help investigators better understand the fundamental causes of atrial fibrillation that prove useful to everyone at risk for AFib, regardless of their race or ethnicity.”

The team plumbed the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) California state databases for information on more than 16 million cases of AFib that occurred during 2005-2011. Native Americans comprised just 0.6% of the cohort. Most of the patients (57.2%) were white; 8% were black, 25.6% Hispanic, and 8.6% Asian. After targeting only new-onset cases, there were 344,469 incident AFib episodes over a median follow-up of 4.1 years.

The overall incidence of AFib in Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years, significantly higher than the 6.89 per 1000 person-years observed in the rest of the cohort ( P less than .0001). The difference remained significant even after the team controlled for age, sex, income, and heart and other diseases. Nor was it altered by a sensitivity analysis that controlled for place of presentation and patients who were aged at least 35 years with at least two encounters with medical facilities.

In an interaction analysis, the increased risk appeared to be driven by higher rates of diabetes and chronic kidney disease, the authors wrote.

“This may suggest that the presence of these two processes contributes some pathophysiology related to AF[ib] risk that may be similar to the heightened risk inherent among American Indians,” they wrote. “It is also important to note that there was no evidence of any other statistically significant interactions despite the inclusion of millions of patients.”

Supporting data for these associations were not included in the research letter.

The authors noted some limitations of their study. Race or ethnicity were self-reported and could not be independently confirmed, so there was no way to tease out the effects in multiracial patients. Also, the database didn’t record outpatient encounters, which might result in some selection bias.

“Last, because this was an observational study, these results should not be interpreted as evidence of causal effect,” they noted.

“In conclusion, we observed that American Indians had a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared with all other racial and ethnic group. The heightened risk … in American Indians persisted after multivariable adjustment for known conventional confounders and mediators, suggesting that an unidentified characteristic, including possible genetic or environmental factors, may be responsible,” the investigators wrote.

The HCUP database is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Marcus reported receiving research support from Jawbone, Medtronic, Eight, and Baylis Medical, and is a consultant for and holds equity in InCarda Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marcus GM et al. Circulation. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042882.

Over 4 years, atrial fibrillation (AFib) developed significantly more often in a group of Native Americans men than it did among other racial and ethnic groups, a large longitudinal cohort study has found.

The overall incidence among Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the incidence in a comparator cohort of black, white, Asian, and Hispanic men, Gregory M. Marcus, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote in a research letter published in Circulation.

“We were surprised to find that American Indians experienced a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared to every other racial and ethnic group,” Dr. Marcus said in a press release that accompanied the study. “Understanding the mechanisms and factors by which American Indians experience this higher risk may help investigators better understand the fundamental causes of atrial fibrillation that prove useful to everyone at risk for AFib, regardless of their race or ethnicity.”

The team plumbed the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) California state databases for information on more than 16 million cases of AFib that occurred during 2005-2011. Native Americans comprised just 0.6% of the cohort. Most of the patients (57.2%) were white; 8% were black, 25.6% Hispanic, and 8.6% Asian. After targeting only new-onset cases, there were 344,469 incident AFib episodes over a median follow-up of 4.1 years.

The overall incidence of AFib in Native Americans was 7.49 per 1,000 person-years, significantly higher than the 6.89 per 1000 person-years observed in the rest of the cohort ( P less than .0001). The difference remained significant even after the team controlled for age, sex, income, and heart and other diseases. Nor was it altered by a sensitivity analysis that controlled for place of presentation and patients who were aged at least 35 years with at least two encounters with medical facilities.

In an interaction analysis, the increased risk appeared to be driven by higher rates of diabetes and chronic kidney disease, the authors wrote.

“This may suggest that the presence of these two processes contributes some pathophysiology related to AF[ib] risk that may be similar to the heightened risk inherent among American Indians,” they wrote. “It is also important to note that there was no evidence of any other statistically significant interactions despite the inclusion of millions of patients.”

Supporting data for these associations were not included in the research letter.

The authors noted some limitations of their study. Race or ethnicity were self-reported and could not be independently confirmed, so there was no way to tease out the effects in multiracial patients. Also, the database didn’t record outpatient encounters, which might result in some selection bias.

“Last, because this was an observational study, these results should not be interpreted as evidence of causal effect,” they noted.

“In conclusion, we observed that American Indians had a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, compared with all other racial and ethnic group. The heightened risk … in American Indians persisted after multivariable adjustment for known conventional confounders and mediators, suggesting that an unidentified characteristic, including possible genetic or environmental factors, may be responsible,” the investigators wrote.

The HCUP database is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Marcus reported receiving research support from Jawbone, Medtronic, Eight, and Baylis Medical, and is a consultant for and holds equity in InCarda Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marcus GM et al. Circulation. 2019 Oct 21. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042882.

FROM CIRCULATION

Pulmonary Hemorrhage as the Initial Presentation of AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

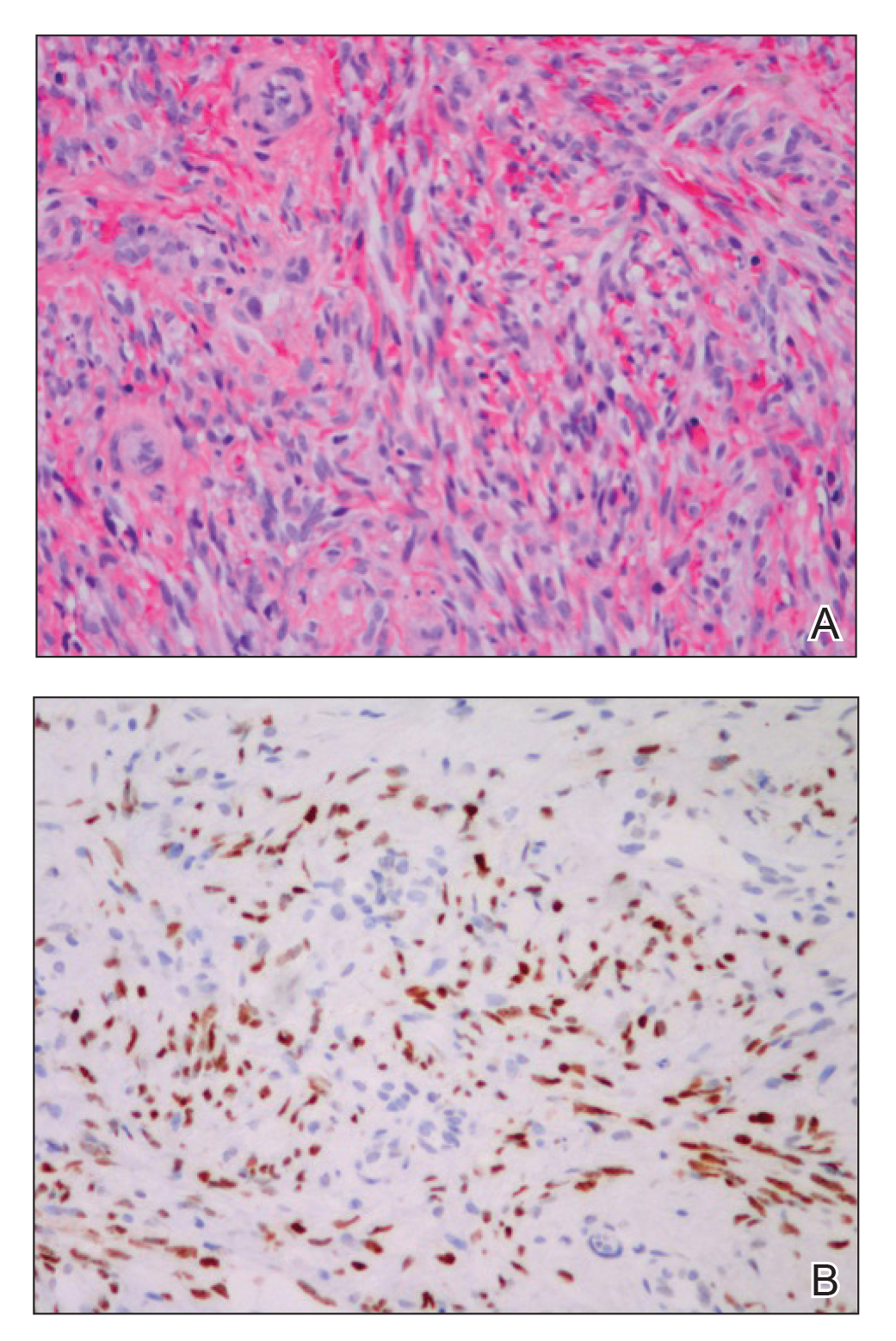

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

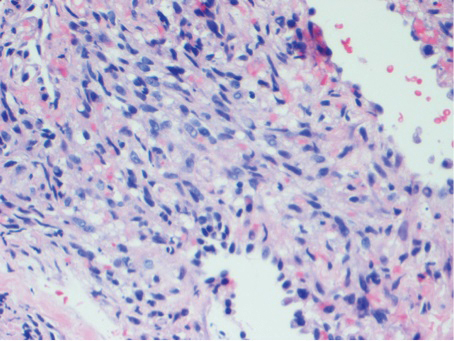

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

Practice Points

- Visceral Kaposi sarcoma (KS) should be considered in patients with unexplained systemic symptoms in the setting of poorly controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- If cutaneous KS is diagnosed in an HIV patient, a detailed history and physical examination should be undertaken to evaluate for signs of systemic disease.

Trastuzumab benefit lasts long-term in HER2+ breast cancer

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Will changing the names of psychiatric medications lead to better treatment?

Back in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association dropped the word “neurosis” from the DSM-III, so that if you had been neurotic, after 1980, you were neurotic no longer.

At the time, I discussed this on my daily radio show. For those folks who were nervous, worried, fearful, and full of anxieties about themselves, their families, welfare, health, and the environment around them, a new set of labels was introduced to more specifically describe one or more problems related to anxiety.

For codification, and at times, a clearer understanding of a specific problem, the change was made to be helpful. Certainly, for insurers and pharmacologic treatments, it worked. However, it’s interesting that the word and concept, neurosis, which still is used by some psychiatrists and psychologists – although not scientific – does offer a clear overall picture of a suffering, anxiety-ridden person who might have a combination of an anxiety disorder, panic attacks, somatic symptoms, and endless worry. This overlapping picture often is seen in clinical practice more than the multiple one-dimensional labels that are currently used. So be it.

This all leads me to what I’ve recently learned about the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN) Project. According to a recent article in the APA’s Psychiatric News, the group’s board of trustees has endorsed a proposal that would change or revise the names of psychiatric medications so that the names reflect their mechanism of action – a move seemingly focused on a pure biological model.

For example, according to the article, the medication perphenazine would be renamed a “D2 receptor antagonist” rather than an antipsychotic. For depression, we might have a serotonergic reuptake inhibitor, according to the report, and of course, the list of changes would go on – based on current knowledge of biological activity. It’s true that in general medicine, there are examples where mode of action is discussed. For example, in cardiology we have beta-blockers and alpha-blockers, which are descriptive of their actions. As doctors who have trained for years and know the mechanism of action of various medications, we will understand all this. But in patient care, both doctors and their patients often understand and feel comfortable using descriptive terms indicating the treatment modality, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, anti-inflammatory medications, as well as anti-itching, antiaging, and antispasmodic drugs.

So, I am concerned about these proposed changes. In an era focused on patient-centered care, where we seek to make it simpler for the patient/health care consumer, we might make it harder for the patient to grasp what’s going on.

It’s very important to keep in mind that we as physicians know the ins and outs of medications, and that even the most educated and bright patients who are not in medicine do not know what our education has taught us. For example, regardless of specialty, we all know the difference between left-sided and right-sided heart failure. Those outside of medicine, however, rarely know the difference. They understand heart disease as a rule. People in general might understand some general concepts, such as RBC, WBC, and platelets. A patient will speak of taking a blood thinner but rarely know or understand the differences between antiplatelets and anticoagulants. And why should they know this?

The point here is that I believe good patient care is keeping it simple and taking the time to explain what’s being treated, aiming to inform patients using down-to-earth, accessible language rather than the language of biochemistry.

It’s true that in psychiatry, wider use of certain medications than originally indicated has grown tremendously as well as off-label use. In light of that, the NbN idea is laudable. However, it would seem more practical to leave the traditional modes of action in place and expand our discussions with patients as to why we are using a specific medication. I have found a very simple and even rewarding way to explain to patients, for example, that yes, this is an antiseizure medication but it is now used in psychiatry as a mood stabilizer.

Another important point is the question of whether using nomenclature that describes the exact location of the problem is all that accurate. Currently, we know we still have a lot to learn about brain chemistry and neuronal transmission in mental disorders, just as in many medical disorders, there are gaps in our understanding of many illnesses and subsequent molecular changes.

Just as the DSM-III left behind the all-encompassing and descriptive word neurosis and the APA has changed labels in the DSM-IV and DSM-5, so the NbN project would change the nomenclature of current psychotropic medications. The intentions are good, but the idea that those changes will foster better patient understanding defies common sense. A better idea might be to continue use of both scientific names and names of commonly used actions of the medications, leaving both in place and letting clinicians decide what nomenclature best suits each patient.

It will be a sad day when psychiatrists become so medically and “scientifically” driven that we cannot explain to a patient, “I’m prescribing this antidepressant because it’s now used to treat anxiety,” or “Yes, this medicine is labeled ‘antipsychotic,’ but you’re not psychotic. It may help your mood swings and may even help you sleep better.” Now, is that hard? Is talking to a person and explaining the treatment no longer part of care? The take-home messages from the recent APA/Institute of Psychiatric Services meeting I attended seemed to suggest that human attention and care have great value. My father, a surgeon, always said that you learn a lot by simply talking to patients – and they learn from you.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019).

Back in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association dropped the word “neurosis” from the DSM-III, so that if you had been neurotic, after 1980, you were neurotic no longer.

At the time, I discussed this on my daily radio show. For those folks who were nervous, worried, fearful, and full of anxieties about themselves, their families, welfare, health, and the environment around them, a new set of labels was introduced to more specifically describe one or more problems related to anxiety.

For codification, and at times, a clearer understanding of a specific problem, the change was made to be helpful. Certainly, for insurers and pharmacologic treatments, it worked. However, it’s interesting that the word and concept, neurosis, which still is used by some psychiatrists and psychologists – although not scientific – does offer a clear overall picture of a suffering, anxiety-ridden person who might have a combination of an anxiety disorder, panic attacks, somatic symptoms, and endless worry. This overlapping picture often is seen in clinical practice more than the multiple one-dimensional labels that are currently used. So be it.

This all leads me to what I’ve recently learned about the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN) Project. According to a recent article in the APA’s Psychiatric News, the group’s board of trustees has endorsed a proposal that would change or revise the names of psychiatric medications so that the names reflect their mechanism of action – a move seemingly focused on a pure biological model.

For example, according to the article, the medication perphenazine would be renamed a “D2 receptor antagonist” rather than an antipsychotic. For depression, we might have a serotonergic reuptake inhibitor, according to the report, and of course, the list of changes would go on – based on current knowledge of biological activity. It’s true that in general medicine, there are examples where mode of action is discussed. For example, in cardiology we have beta-blockers and alpha-blockers, which are descriptive of their actions. As doctors who have trained for years and know the mechanism of action of various medications, we will understand all this. But in patient care, both doctors and their patients often understand and feel comfortable using descriptive terms indicating the treatment modality, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, anti-inflammatory medications, as well as anti-itching, antiaging, and antispasmodic drugs.

So, I am concerned about these proposed changes. In an era focused on patient-centered care, where we seek to make it simpler for the patient/health care consumer, we might make it harder for the patient to grasp what’s going on.

It’s very important to keep in mind that we as physicians know the ins and outs of medications, and that even the most educated and bright patients who are not in medicine do not know what our education has taught us. For example, regardless of specialty, we all know the difference between left-sided and right-sided heart failure. Those outside of medicine, however, rarely know the difference. They understand heart disease as a rule. People in general might understand some general concepts, such as RBC, WBC, and platelets. A patient will speak of taking a blood thinner but rarely know or understand the differences between antiplatelets and anticoagulants. And why should they know this?

The point here is that I believe good patient care is keeping it simple and taking the time to explain what’s being treated, aiming to inform patients using down-to-earth, accessible language rather than the language of biochemistry.

It’s true that in psychiatry, wider use of certain medications than originally indicated has grown tremendously as well as off-label use. In light of that, the NbN idea is laudable. However, it would seem more practical to leave the traditional modes of action in place and expand our discussions with patients as to why we are using a specific medication. I have found a very simple and even rewarding way to explain to patients, for example, that yes, this is an antiseizure medication but it is now used in psychiatry as a mood stabilizer.

Another important point is the question of whether using nomenclature that describes the exact location of the problem is all that accurate. Currently, we know we still have a lot to learn about brain chemistry and neuronal transmission in mental disorders, just as in many medical disorders, there are gaps in our understanding of many illnesses and subsequent molecular changes.

Just as the DSM-III left behind the all-encompassing and descriptive word neurosis and the APA has changed labels in the DSM-IV and DSM-5, so the NbN project would change the nomenclature of current psychotropic medications. The intentions are good, but the idea that those changes will foster better patient understanding defies common sense. A better idea might be to continue use of both scientific names and names of commonly used actions of the medications, leaving both in place and letting clinicians decide what nomenclature best suits each patient.

It will be a sad day when psychiatrists become so medically and “scientifically” driven that we cannot explain to a patient, “I’m prescribing this antidepressant because it’s now used to treat anxiety,” or “Yes, this medicine is labeled ‘antipsychotic,’ but you’re not psychotic. It may help your mood swings and may even help you sleep better.” Now, is that hard? Is talking to a person and explaining the treatment no longer part of care? The take-home messages from the recent APA/Institute of Psychiatric Services meeting I attended seemed to suggest that human attention and care have great value. My father, a surgeon, always said that you learn a lot by simply talking to patients – and they learn from you.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019).

Back in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association dropped the word “neurosis” from the DSM-III, so that if you had been neurotic, after 1980, you were neurotic no longer.

At the time, I discussed this on my daily radio show. For those folks who were nervous, worried, fearful, and full of anxieties about themselves, their families, welfare, health, and the environment around them, a new set of labels was introduced to more specifically describe one or more problems related to anxiety.

For codification, and at times, a clearer understanding of a specific problem, the change was made to be helpful. Certainly, for insurers and pharmacologic treatments, it worked. However, it’s interesting that the word and concept, neurosis, which still is used by some psychiatrists and psychologists – although not scientific – does offer a clear overall picture of a suffering, anxiety-ridden person who might have a combination of an anxiety disorder, panic attacks, somatic symptoms, and endless worry. This overlapping picture often is seen in clinical practice more than the multiple one-dimensional labels that are currently used. So be it.

This all leads me to what I’ve recently learned about the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN) Project. According to a recent article in the APA’s Psychiatric News, the group’s board of trustees has endorsed a proposal that would change or revise the names of psychiatric medications so that the names reflect their mechanism of action – a move seemingly focused on a pure biological model.

For example, according to the article, the medication perphenazine would be renamed a “D2 receptor antagonist” rather than an antipsychotic. For depression, we might have a serotonergic reuptake inhibitor, according to the report, and of course, the list of changes would go on – based on current knowledge of biological activity. It’s true that in general medicine, there are examples where mode of action is discussed. For example, in cardiology we have beta-blockers and alpha-blockers, which are descriptive of their actions. As doctors who have trained for years and know the mechanism of action of various medications, we will understand all this. But in patient care, both doctors and their patients often understand and feel comfortable using descriptive terms indicating the treatment modality, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, anti-inflammatory medications, as well as anti-itching, antiaging, and antispasmodic drugs.

So, I am concerned about these proposed changes. In an era focused on patient-centered care, where we seek to make it simpler for the patient/health care consumer, we might make it harder for the patient to grasp what’s going on.

It’s very important to keep in mind that we as physicians know the ins and outs of medications, and that even the most educated and bright patients who are not in medicine do not know what our education has taught us. For example, regardless of specialty, we all know the difference between left-sided and right-sided heart failure. Those outside of medicine, however, rarely know the difference. They understand heart disease as a rule. People in general might understand some general concepts, such as RBC, WBC, and platelets. A patient will speak of taking a blood thinner but rarely know or understand the differences between antiplatelets and anticoagulants. And why should they know this?

The point here is that I believe good patient care is keeping it simple and taking the time to explain what’s being treated, aiming to inform patients using down-to-earth, accessible language rather than the language of biochemistry.

It’s true that in psychiatry, wider use of certain medications than originally indicated has grown tremendously as well as off-label use. In light of that, the NbN idea is laudable. However, it would seem more practical to leave the traditional modes of action in place and expand our discussions with patients as to why we are using a specific medication. I have found a very simple and even rewarding way to explain to patients, for example, that yes, this is an antiseizure medication but it is now used in psychiatry as a mood stabilizer.

Another important point is the question of whether using nomenclature that describes the exact location of the problem is all that accurate. Currently, we know we still have a lot to learn about brain chemistry and neuronal transmission in mental disorders, just as in many medical disorders, there are gaps in our understanding of many illnesses and subsequent molecular changes.

Just as the DSM-III left behind the all-encompassing and descriptive word neurosis and the APA has changed labels in the DSM-IV and DSM-5, so the NbN project would change the nomenclature of current psychotropic medications. The intentions are good, but the idea that those changes will foster better patient understanding defies common sense. A better idea might be to continue use of both scientific names and names of commonly used actions of the medications, leaving both in place and letting clinicians decide what nomenclature best suits each patient.

It will be a sad day when psychiatrists become so medically and “scientifically” driven that we cannot explain to a patient, “I’m prescribing this antidepressant because it’s now used to treat anxiety,” or “Yes, this medicine is labeled ‘antipsychotic,’ but you’re not psychotic. It may help your mood swings and may even help you sleep better.” Now, is that hard? Is talking to a person and explaining the treatment no longer part of care? The take-home messages from the recent APA/Institute of Psychiatric Services meeting I attended seemed to suggest that human attention and care have great value. My father, a surgeon, always said that you learn a lot by simply talking to patients – and they learn from you.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019).

Is carpal tunnel syndrome the tip of the iceberg?

He takes the following medications: felodipine and atorvastatin. On exam, his blood pressure is 110/60 mm Hg, and his pulse is 90 beats per minute.

A cardiac examination found normal heart sounds with no murmurs.

A chest examination found dullness to percussion at both bases and rales.

A chest x-ray showed bilateral effusions and mild pulmonary edema.

The brain natriuretic peptide test found a level of 1,300 picograms/mL.

An ECG found increased ventricular wall thickness, an ejection fraction of 32%, and normal aortic and mitral valves.

What history would be the most helpful in making a diagnosis?

A. History of prostate cancer

B. History of carpal tunnel syndrome

C. History of playing professional football

D. History of hyperlipidemia

E. History of ulcerative colitis

The correct answer here would be B. history of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). This patient has clinical heart failure, without a history of clinical ischemic disease. The differential diagnosis for causes of heart failure is long, with the most common causes being chronic hypertension and ischemic heart disease. Other common causes include chronic untreated sleep apnea and valvular heart disease.

This patient really does not have clear reasons for having clinical heart failure. His cardiovascular risk factors have been well controlled, and no valvular disease was found on ECG.

Several recent reports have raised the importance of a history of CTS significantly increasing the likelihood of amyloidosis being the cause of underlying heart failure.

CTS is such a common clinical entity that it is easy to not appreciate its presence as a clue to possible amyloid cardiomyopathy. Fosbøl et al. reported that a diagnosis of CTS was associated with a higher incidence of heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.54; CI, 1.45-1.64).1 They found a highly increased risk of amyloid (HR, 12.2) in patients who had surgery for CTS.

Sperry et al. found that over 10% of patients who underwent carpal tunnel release stained for amyloid on biopsy specimens, and that concomitant cardiac evaluation identified patients with cardiac involvement.2

Pinney et al. found that 48% of patients with transthyretin amyloidosis had a history of CTS.3

In a retrospective study of patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloid (253), patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloid (136), and asymptomatic gene carriers (77), participants were screened for a history of spinal stenosis and CTS.4 Almost 60% of the patients with amyloid had a history of CTS, and 11% had a history of spinal stenosis. Patients with CTS and hereditary amyloid had thicker interventricular septums, higher left ventricular mass, and lower Karnovsky index than those without CTS.

The diagnosis of CTS, especially in those who need surgery for treatment or have bilateral disease, should make us consider the possibility of underlying amyloidosis.

Pearl: In patients who have heart failure and a history of CTS, amyloidosis should be considered as a cause.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at imnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Fosbøl EL et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:15-23.

2. Sperry BW et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Oct 23;72(17):2040-50.

3. Pinney JH et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013 Apr 22;2(2):e000098.

4. Aus dem Siepen F et al. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019 Apr 5. doi: 10.1007/s00392-019-01467-1.

He takes the following medications: felodipine and atorvastatin. On exam, his blood pressure is 110/60 mm Hg, and his pulse is 90 beats per minute.

A cardiac examination found normal heart sounds with no murmurs.

A chest examination found dullness to percussion at both bases and rales.

A chest x-ray showed bilateral effusions and mild pulmonary edema.

The brain natriuretic peptide test found a level of 1,300 picograms/mL.

An ECG found increased ventricular wall thickness, an ejection fraction of 32%, and normal aortic and mitral valves.

What history would be the most helpful in making a diagnosis?

A. History of prostate cancer

B. History of carpal tunnel syndrome

C. History of playing professional football

D. History of hyperlipidemia

E. History of ulcerative colitis

The correct answer here would be B. history of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). This patient has clinical heart failure, without a history of clinical ischemic disease. The differential diagnosis for causes of heart failure is long, with the most common causes being chronic hypertension and ischemic heart disease. Other common causes include chronic untreated sleep apnea and valvular heart disease.

This patient really does not have clear reasons for having clinical heart failure. His cardiovascular risk factors have been well controlled, and no valvular disease was found on ECG.

Several recent reports have raised the importance of a history of CTS significantly increasing the likelihood of amyloidosis being the cause of underlying heart failure.

CTS is such a common clinical entity that it is easy to not appreciate its presence as a clue to possible amyloid cardiomyopathy. Fosbøl et al. reported that a diagnosis of CTS was associated with a higher incidence of heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.54; CI, 1.45-1.64).1 They found a highly increased risk of amyloid (HR, 12.2) in patients who had surgery for CTS.

Sperry et al. found that over 10% of patients who underwent carpal tunnel release stained for amyloid on biopsy specimens, and that concomitant cardiac evaluation identified patients with cardiac involvement.2

Pinney et al. found that 48% of patients with transthyretin amyloidosis had a history of CTS.3