User login

Right ankle pain and swelling

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic enthesitis.

Enthesitis is a hallmark manifestation of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis are estimated to be affected by PsA, which belongs to the spondyloarthritis (SpA) family of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

An enthesis is an attachment site of ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules to bone and is a key inflammatory target in SpA. It is a complex structure that dissipates biomechanical stress to preserve homeostasis. Entheses are anatomically and functionally integrated with bursa, fibrocartilage, and synovium in a synovial entheseal complex; biomechanical stress in this area may trigger inflammation. Enthesitis is an early manifestation of PsA that has been associated with radiographic peripheral/axial joint damage and severe disease, as well as reduced quality of life.

Enthesitis can be difficult to diagnose in clinical practice. Symptoms include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation, often without overt clinical evidence of inflammation. In contrast, dactylitis, another hallmark manifestation of PsA, can be recognized by swelling of an entire digit that is different from adjacent digits. Fibromyalgia frequently coexists with enthesitis, and it can be difficult to distinguish the two given the anatomic overlap between the tender points of fibromyalgia and many entheseal sites. Long-lasting morning stiffness and a sustained response to a course of steroids is more suggestive of enthesitis, whereas a higher number of somatoform symptoms is more suggestive of fibromyalgia.

Enthesitis is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as a hallmark of PsA. While it can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be required, particularly in patients in whom symptoms may be difficult to discern. Evidence of enthesitis by conventional radiography includes bone cortex irregularities, erosions, entheseal soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation; however, entheseal bone changes detected with conventional radiography appear relatively late in the disease process. Ultrasound is highly sensitive for assessing inflammation and can detect various features of enthesitis, such as increased thickness of tendon insertion, hypoechogenicity, erosions, enthesophytes, and subclinical enthesitis in people with PsA. MRI has the advantage of identifying perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema. Fat-suppressed MRI with or without gadolinium enhancement is a highly sensitive method for visualizing active enthesitis and can identify perientheseal inflammation with adjacent bone marrow edema.

Delayed treatment of PsA can result in irreversible joint damage and reduced quality of life; thus, patients with psoriasis should be closely monitored for early signs of its development, such as enthesitis. A thorough evaluation of the key clinical features of PsA (psoriasis, arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), including evaluation of severity of each feature and impact on physical function and quality of life, is encouraged at each clinical encounter. Because patients may not understand the link between psoriasis and joint pain, specific probing questions can be helpful. Screening questionnaires to detect early signs and symptoms of PsA are available, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST), Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening (ToPAS) questionnaire. These and many others may be used to help dermatologists detect early signs and symptoms of PsA. Although these questionnaires all have limitations in sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PsA, their use can still improve early diagnosis.

The treatment of PsA focuses on achieving the least amount of disease activity and inflammation possible; optimizing functional status, quality of life, and well-being; and preventing structural damage. Treatment decisions are based on the specific domains affected. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections are first-line treatments for enthesitis. Early use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab) is recommended. Alternative biologic disease-modifying agents are indicated when these TNF inhibitors provide an inadequate response. They include ustekinumab (dual interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23 inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) and may be considered for patients with predominantly entheseal manifestations of PsA or dactylitis. Biological disease-modifying agents approved for PsA that have shown efficacy for enthesitis include ixekizumab (which targets IL-17A), abatacept (a T-cell inhibitor), guselkumab (monoclonal antibody), and ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody). Tofacitinib and upadacitinib, both oral Janus kinase inhibitors, may also be considered.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 42-year-old woman with a 20-year history of plaque psoriasis presents with complaints of a 3-month history of pain, tenderness, and swelling in her right ankle and foot, of unknown origin. Physical examination reveals active psoriasis, with a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 6.7 and psoriatic nail dystrophy, including onycholysis, pitting, and hyperkeratosis. Tenderness and swelling are noted at the back of the heel. The patient denies any other complaints. Laboratory tests are normal, including negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear factor. MRI reveals soft tissue and bone marrow edema below the Achilles insertion.

Decline in ambulatory function

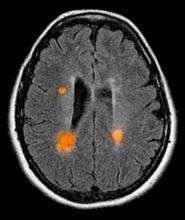

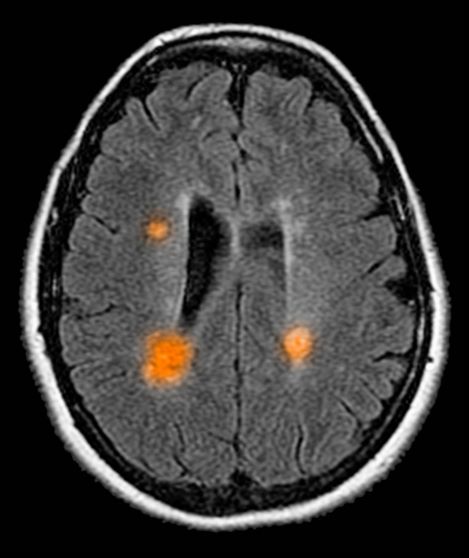

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on this patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). PPMS represents around 10% of MS cases and tends to develop about a decade later than relapsing MS. Unlike other forms of MS, this phenotype progresses steadily instead of in an episodic fashion like relapsing forms of MS. Most patients with PPMS present with gait difficulty because lesions often develop on the spinal cord. While relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is much more common among women than men, men with MS are more likely to have the progressive form.

Although this patient's MRI ultimately points to multiple sclerosis, his functional deficits may initially suggest other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Brainstem gliomas typically manifest in unsteady gait, weakness, double vision, difficulty swallowing, dysarthria, headache, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Transverse myelitis often presents with rapid-onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Musculoskeletal and neurologic symptoms are common in Lyme disease. B12 deficiency can present with worsening weakness and a sensory ataxia that can present as balance difficulties, but it would not cause focal lesions on the MRI, nor would it present with bladder symptoms. In addition, the patient's steady decline in function rules out RRMS.

PPMS is diagnosed with confirmation of gradual change in functional ability (often ambulation) over time without remission or relapse. These criteria include 1 full year of worsening neurologic function without asymptomatic periods as well as two of these signs of disease: brain lesion, two or more spinal cord lesions, and oligoclonal bands or elevated Immunoglobulin G index. These timing-specific criteria can delay diagnosis, as seen here.

Ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT) proven to alter disease progression in ambulatory patients with PPMS. American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend ocrelizumab for patients with PPMS who are likely to benefit from this therapy. While it is thought that DMTs are more effective at targeting inflammation in RRMS than nerve degeneration in PPMS, these agents may show benefit for patients with active PPMS (relapse and/or evidence of new MRI activity) rather than inactive disease. A recent PPMS study concluded that among patients with relapse or disease activity, DMTs were associated with a significant reduction of long-term disability risk. Together with immunomodulatory therapy, rehabilitation can help manage symptoms.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 59-year-old man presents with worsening decline in ambulatory function and worsening bladder function. He reports "difficulty getting around" for the past year and a half, which he theorized might be because of arthritis, aging, or many years of biking. He presented to his primary care physician 2 months ago and was referred to rheumatology. His height is 5 ft 11 in and his weight is 166 lb (BMI 23.1). The patient subsequently reported a decreased attention span to the rheumatologist. He has no other significant medical or surgical history, though his brother has psoriatic arthritis. MRI shows multiple brain lesions without gadolinium enhancement and multiple spinal cord lesions.

Chest tightness and wheezing

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical examination and imaging findings are consistent with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Agitation, breathlessness during rest, and a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min are some manifestations of an acute severe episode. During severe episodes, accessory muscles of respiration are usually used, and suprasternal retractions are often present. The heart rate is > 120 beats/min and the respiratory rate is > 30 breaths/min. Loud biphasic (expiratory and inspiratory) wheezing can be heard, and pulsus paradoxus is often present (20-40 mm Hg). Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is < 91%. As the severity increases, the patient increasingly assumes a hunched-over sitting position with the hands supporting the torso, termed the tripod position.

Asthma is a chronic, heterogenous inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable expiratory flow; airway wall thickening; respiratory symptoms; and exacerbations, which sometimes require hospitalization. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people in 2019. The presence of airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchial hyperreactivity in asthma is an exaggerated response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Mechanisms implicated in the development of asthma include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by pharmacologically active substances from mediator-secreting cells, such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons. The degree of airway hyperresponsiveness is associated with the clinical severity of asthma.

Acute severe asthma is a life-threatening emergency characterized by severe airflow limitation that is unresponsive to the typical appropriate bronchodilator therapy. As a result of pathophysiologic changes, airflow is severely restricted in severe asthma, leading to premature closure of the airway on expiration; impaired gas exchange; and dynamic hyperinflation, or air-trapping. In such cases, urgent action is essential to thwart serious outcomes, including mechanical ventilation and death.

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to control a patient's symptoms and exacerbations. According to the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, a severe asthma exacerbation describes a patient who talks in words (rather than sentences); leans forward; is agitated; uses accessory respiratory muscles; and has a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, heart rate > 120 beats/min, oxygen saturation on air < 90%, and peak expiratory flow ≤ 50% of their best or of predicted value. Given the heterogeneity of asthma, patients with acute severe asthma may present with a variety of signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing, agitation, drowsiness or signs of confusion, and significant breathlessness at rest.

Exposure to external agents, such as indoor and outdoor allergens, air pollutants, and respiratory tract infections (primarily viral), are the most common causes of asthma exacerbations, which vary in severity. Numerous other factors can trigger an asthma exacerbation, including exercise, weather changes, certain foods, additives, drugs, extreme emotional expressions, rhinitis, sinusitis, polyposis, gastroesophageal reflux, menstruation, and pregnancy. Importantly, a patient with known asthma of any level of severity can experience an asthma exacerbation, including patients with mild or well-controlled asthma.

Patients with a history of poorly controlled asthma or a recent exacerbation are at risk for an acute asthma exacerbation. Other risk factors include poor perception of airflow limitation, regular or overuse of short-acting beta agonists, incorrect inhaler technique, and suboptimal adherence to therapy. Comorbidities associated with risk for an acute asthma exacerbation include obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, inducible laryngeal obstruction (vocal cord dysfunction), gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchiectasis, cardiac disease, and kyphosis due to osteoporosis (followed by corticosteroid overuse). The lack of a written asthma action plan and socioeconomic factors are also associated with increased risk for a severe exacerbation.

In the emergency department setting, pharmacologic therapy of acute severe asthma should consist of a short-acting beta agonist, ipratropium bromide, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous), and controlled oxygen therapy. Clinicians may also consider intravenous magnesium sulfate and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Once stable, patients should be treated with optimal asthma-controlling therapy, as outlined in GINA guidelines. Optimizing patients' inhaler technique and adherence to therapy are imperative, and comorbidities should be appropriately managed. Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise, weight loss, and influenza/COVID-19 vaccination, are also recommended as indicated.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 32-year-old Black man presents to the emergency department with severe dyspnea, chest tightness, and wheezing. The patient is sitting forward in the tripod position and appears agitated and confused. Use of accessory respiratory muscles and suprasternal retractions are noted. He reports an approximate 2-week history of rhinorrhea, cough, and mild fever, for which he has been taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent and cough suppressant. His prior medical history is notable for obesity, type 2 diabetes, allergic rhinitis, mild asthma, and hypercholesterolemia. The patient is a current smoker (17 pack-years). Pertinent physical examination reveals a respiratory rate of 48 breaths/min, heart rate of 135 beats/min, 87% oxygen saturation, and peak expiratory flow of 300 L/min. Low biphasic wheezing can be heard. Rapid antigen and PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 detected by nasopharyngeal swabs both come back negative. Chest radiography is ordered and shows pulmonary hyperinflation with bronchial wall thickening.

Complaints of foot pain

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 59-year-old woman newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and hypercholesterolemia presents with complaints of foot pain, particularly while wearing shoes. Physical examination reveals an extended metatarsophalangeal joint, a flexed proximal interphalangeal joint, and flexed distal interphalangeal joint. Her toenails are discolored with a yellowish hue, and callus formation is noted over the metatarsal area. The patient reports pain at the tip of the toe from pressure against the point of the distal phalanx. She states that she has not experienced any numbness, tingling, or muscle weakness. Before her recent diabetes diagnosis, the patient had not been receiving regular medical care. The patient's current medications include metformin 500 mg/d, empagliflozin 10 mg/d, and rosuvastatin 10 mg/d.

Severe abdominal pain and vomiting

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 12-year-old boy presents to an urgent care center with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His height is 5 ft 3 in and weight is 99 lb (BMI 18.7). The patient has a history of chronic diarrhea and reports intermittent abdominal pain that began about 6 months ago. During this time, he has lost about 12 lb, as many foods exacerbate his symptoms, though his mother notes that even plain foods can bother his stomach. Further questioning reveals that his father has moderate Crohn disease (age of onset, 29 years), his sister has celiac disease, and the patient is of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. His body temperature is 100.2 °F. Vitamin B12, serum iron, total iron binding capacity, calcium, and magnesium are low. Stool cultures are negative. Ileocolonoscopy shows small aphthous erosions in the large intestine and in the terminal ileum.

Severe pulsing headache

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 18-year-old female patient presents with severe pulsing headache that began about 6 hours earlier. She describes feeling tired and irritable for the past 2 days and that she has had difficulty concentrating. Earlier in the day, before headache onset, she became extremely fatigued. Describing a "blinding light" in her vision, she is currently highly photophobic. The patient took four ibuprofen 2 hours ago. There is no significant medical history. She is on a regimen of estrogen-progestin and spironolactone for acne. Following advice from her primary care practitioner, she takes magnesium and vitamin B for headache prevention. The patient reports that she does not believe that she has migraines because she has never vomited during an episode. The patient explains that she has always had frequent headaches but that this is the sixth or seventh episode of this type and severity that she has had in the past year. The headaches do not seem to align with her menstrual cycle.

Paresthesias along forearm

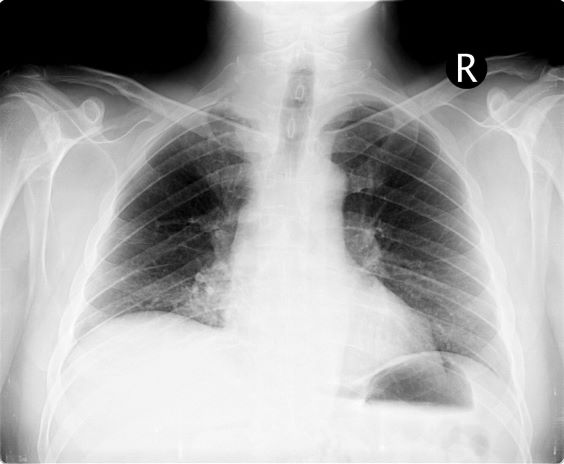

On the basis of this presentation, and the findings from the chest x-ray (as shown), the likely diagnosis is non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Pancoast tumor, also known as superior sulcus tumor. Pancoast tumors are rare, representing about 3%-5% of all lung cancers, and invade the structures in the apex of the chest, including the first thoracic ribs or periosteum, the lower nerve roots of the bronchial plexus, the sympathetic chain and stellate ganglion, or the subclavian vessels. The majority of Pancoast tumors are non–small cell carcinomas.

Because of their pulmonary location, Pancoast tumors are characterized by several distinct symptoms. As seen in this case, patients often present with shoulder pain that worsens over time, especially with invasion of the chest wall and brachial plexus. The pain may radiate to the neck; axilla; anterior chest wall; and medial aspect of the arm, forearm, and wrist. If Pancoast tumors infiltrate the ulnar nerve, patients may present with weakness and muscle atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. In addition, invasion of the sympathetic chain and of the inferior cervical ganglion can cause Horner syndrome (ptosis, miosis, enophthalmos, and anhidrosis). Lastly, upper-arm edema may develop, signaling invasion and potentially occlusion of the subclavian vein.

During workup, CT-guided core biopsy is the first-line diagnostic test for Pancoast tumors. CT of the chest can confirm the presence of an apical mass and its position in relation to other structures of the thoracic inlet. MRI can further assess suspected brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, spine, and neural foramina invasion, specifying the extent of the disease and of the amount of nerve-root involvement.

For resectable Pancoast tumors, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemoradiation, followed by surgical resection and chemotherapy. Preoperative chemoradiation together with surgical resection has shown a 2-year survival between 50% and 70%. Depending on biomarker status (certain EGFR mutations or programmed death ligand 1 levels ≥ 1%), the addition of either atezolizumab or osimertinib is advised. However, the positioning of Pancoast tumors can pose a surgical challenge, and if the lesion remains unresectable after preoperative concurrent chemoradiation, then consolidation immunotherapy with durvalumab is recommended.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of this presentation, and the findings from the chest x-ray (as shown), the likely diagnosis is non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Pancoast tumor, also known as superior sulcus tumor. Pancoast tumors are rare, representing about 3%-5% of all lung cancers, and invade the structures in the apex of the chest, including the first thoracic ribs or periosteum, the lower nerve roots of the bronchial plexus, the sympathetic chain and stellate ganglion, or the subclavian vessels. The majority of Pancoast tumors are non–small cell carcinomas.

Because of their pulmonary location, Pancoast tumors are characterized by several distinct symptoms. As seen in this case, patients often present with shoulder pain that worsens over time, especially with invasion of the chest wall and brachial plexus. The pain may radiate to the neck; axilla; anterior chest wall; and medial aspect of the arm, forearm, and wrist. If Pancoast tumors infiltrate the ulnar nerve, patients may present with weakness and muscle atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. In addition, invasion of the sympathetic chain and of the inferior cervical ganglion can cause Horner syndrome (ptosis, miosis, enophthalmos, and anhidrosis). Lastly, upper-arm edema may develop, signaling invasion and potentially occlusion of the subclavian vein.