User login

HIV Infection: What Primary Care Providers Need to Know

CE/CME No: CR-1405

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the current recommendations for HIV screening.

• Describe the current recommendations for pre- and postexposure HIV prophylaxis.

• Recognize the constellation of symptoms and signs that may represent a patient presenting with acute (primary) HIV infection.

• Discuss the initial evaluation and management of a patient with HIV.

• Compare and contrast the preferred regimens for previously untreated patients with HIV in terms of the key features of the regimens’ components and the rationale for using one versus another.

FACULTY

Susan LeLacheur is an Associate Professor of PA Studies at The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, DC.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.5 hours of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category I CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of May 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

Over the decades, HIV infection has transitioned from an almost universally deadly infection to a chronic, manageable disease. Increased survival, along with improved access to health care and screening, has allowed far more patients to live relatively normal lives. But primary care providers need to stay up to date on all aspects of the disease in order to provide the best possible care to those affected and aid efforts to stem the spread of disease.

Patients with HIV infection whose disease is well controlled can now live a normal lifespan. Because of this increase in lifespan, along with increased health care coverage through the Affordable Care Act, primary care clinicians will be increasingly responsible for the care of patients with HIV. In order to offer optimal treatment, however, clinicians must remain current on HIV screening, initial treatment, and ongoing management. New therapies and simplified regimens have improved HIV care, but diligence in monitoring for complications of HIV and its treatment is needed in order to optimize care.

Consider, for example, a 19-year-old man who comes into your primary care office complaining of a sore throat, malaise, and a generalized rash. On exam, you note cervical adenopathy and a widely scattered rash, mainly on his trunk. His throat is mildly erythematous without exudates. You do a rapid test for strep and for mononucleosis, both of which are negative. A viral syndrome seems the most likely diagnosis, but if you neglect to get a sexual and drug history, you might not think of HIV as the virus in question. And even if routine HIV antibody screening is done as recommended, HIV antibodies have likely not yet developed. This is a classic presentation of acute retroviral syndrome, easily confused with a myriad of less consequential infections. Most cases of HIV are not detected at this stage, although it is estimated that between 50% and 90% of patients with acute HIV infection seek medical care.1-4 The patient with acute HIV and potentially many others can be spared significant harm if HIV is part of your differential diagnosis.

Primary care clinicians play a key role in all aspects of HIV care, starting with HIV prevention through screening, helping HIV-negative patients reduce the risk for infection, and helping to assure that HIV-positive patients are less likely to spread the disease because their own infection is fully suppressed. Primary care providers will also become increasingly involved in the care of patients who are living with HIV. Just as with diabetes or hypertension, patients already HIV infected can be largely managed by knowledgeable primary care clinicians. The required knowledge includes an understanding of the latest recommendations for screening, both pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis, and the initial work-up and ongoing management of patients diagnosed with HIV. Expert consultation is often helpful and will be critical in many cases, but all providers should have a working knowledge of HIV care.

On the next page: Screening and prevention >>

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

When discussing many disease processes, prevention is relegated to the end of the discussion—but with HIV, prevention must be a primary concern for patients and providers. HIV prevention includes two critical strategies: finding previously undiagnosed cases of the infection and preventing transmission through treatment of those with the disease, safer sex practices, or prophylactic antiretroviral therapy for those at highest risk. (Chemoprophylaxis for those who have had a potential exposure is referred to as postexposure prophylaxis, or PEP. Chemoprophylaxis for those at high risk for exposure is termed pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.)

Guidelines published by the CDC in 2006 recommended that clinicians include HIV screening as a routine part of medical care for all patients and that barriers to routine HIV testing be removed. Since then, the estimated proportion of people infected with HIV who are unaware of their HIV-positive status has dropped from about 25% to 16%.5-7 In applying these recommendations to a primary care setting, the practitioner simply adds an HIV antibody test to the standard panel given to new patients. In addition, established patients who have not previously been tested should be advised to have a baseline HIV test regardless of risk.

Clinicians should offer HIV testing on an opt-out basis and inform patients that the test is recommended; patients can refuse the test should they choose to do so. Patients at higher risk for HIV should undergo retesting annually—or more frequently if indicated. Routine testing need not be accompanied by prevention counseling or special consent. While counseling on safer sex or other risk reduction strategies is always appropriate, it should not be seen as an impediment to routine screening.

Newer fourth-generation immunofluorescence assays (IA) detect both HIV-1 and HIV-2 earlier after infection because they are able to detect the HIV viral capsid protein p24 as well as HIV antibodies. If the initial assay is positive, subsequent confirmatory testing with a discrimination assay will distinguish between the two types of HIV. Because the newer IA tests detect antibody much earlier, using the discrimination assay as the confirmatory test rather than a Western blot has become commonplace, although either test may be used. Home testing for HIV is also available. Patients who obtain a positive result are instructed to have the result confirmed by their health care provider.

Neither rapid tests nor home tests will pick up new infections during initial infection (known as the window period prior to the development of detectable antibodies) but they can be very helpful in screening programs since the patient need not return for a second visit to obtain results. Whatever test is initially used, it is important to confirm its results with a second test; for instance, the first test might be a fourth-generation IA (either a rapid test or traditional), confirmed by a discrimination assay or Western blot. If the confirmatory test is negative or indeterminate, an HIV RNA (viral load) test should be considered.8 HIV RNA should also be used whenever a new infection is suspected.

PRE- AND POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

PEP to prevent HIV seroconversion following a possible or confirmed HIV exposure is now well accepted, whether the exposure is occupational or not.9,10 Clinicians should start PEP as soon as possible after exposure, preferably within two hours, but no later than 72 hours after exposure. Do not delay treatment even if the source's or exposed patient’s HIV status or other factors are unknown. Treatment can always be discontinued or modified when further information becomes available.

The most recent update issued by the US Public Health Service includes a change to prior guidelines. They now recommend that all potentially exposed individuals receive a three-drug combination of tenofovir 300 mg orally once daily, emtricitabine 200 mg orally once daily (coformulated as Truvada), and raltegravir 400 mg orally twice daily. Patients should be instructed to continue antiretroviral medications for four weeks. Raltegravir, an integrase inhibitor, has replaced previously recommended drugs used in a three-drug regimen because of its lower incidence of adverse effects as compared to older antiretrovirals. Alternative regimens may be used for a variety of reasons, but the need for an alternative should generally spur expert consultation.

The use of three drugs in all cases is based both on a better understanding of the pathophysiology of HIV and on the availability of medications that are better tolerated. Expert consultation is always helpful in cases of PEP, but particularly in those complicated by pregnancy or breastfeeding, known or suspected drug resistance in the source patient, unknown HIV status of the source patient, delayed report of exposure (> 72 hours), or significant medical illness of the exposed patient. In addition, any toxicity experienced should spur expert consultation. If local expert resources are unavailable, immediate assistance can be obtained through the National Clinicians' Postexposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at (888) 448-4911.

Whenever possible, the source patient should undergo testing if his or her HIV status is unknown. If the exposed patient chooses to receive PEP, it is helpful to evaluate the source patient’s history of medication resistance, which should be done by a clinician with HIV expertise. In all cases, the likelihood of HIV conversion after an exposure is low, ranging from approximately 0.3% for a percutaneous exposure to 0.09% for a mucous membrane exposure.11,12

Clinicians should test the exposed patient for HIV and hepatitis B and C, and women should have a pregnancy test performed. For patients being treated, renal and hepatic function should be evaluated and hematology tests done to monitor for adverse reactions to therapy at baseline, two weeks, and completion of treatment. The exposed patient must be advised to take precautions to avoid any potential for transmission of HIV: use barrier contraception and avoid blood or tissue donation or breastfeeding until after the final follow-up visit. Initial follow-up should occur within 72 hours to reevaluate the need for therapy and reinforce the need for adherence if therapy is continued. Clinicians should also assess the patient regarding his or her emotional as well as physical well-being and access to resources to aid in coping with the event. If a fourth-generation test is used, follow-up HIV testing should be done at six weeks and four months after exposure. Otherwise, follow-up HIV testing should occur at six weeks, 12 weeks, and six months.

PrEP using tenofovir 300 mg orally once daily and emtricitabine 200 mg orally once daily is recommended in interim CDC guidelines for those at particularly high risk for HIV exposure, such as homosexual or heterosexual partners of HIV-positive individuals or injection drug users. For PrEP to be effective, medication adherence is critical. Because PrEP involves daily therapy, patients should be carefully selected and expert consultation is advised.13,14 All patients on PrEP require regular follow-up and HIV testing. On follow-up, side effects and continued risk should be evaluated. PrEP should be considered part of a broader prevention strategy that includes condom use, prevention and treatment of other sexually transmitted infections, and frequent reassessment of risk. There are often significant difficulties in obtaining insurance coverage for PrEP, but this may change as further research is done and health care coverage broadens.

On the next page: Recognizing and managing acute HIV >>

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING ACUTE HIV

As noted above, the symptoms of acute (or primary) retroviral syndrome can suggest numerous other infectious processes, including mononucleosis, influenza, or the common cold. The most common symptoms are fever, fatigue, and malaise, but arthralgias, headache, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, and pharyngitis are also common. The severity of symptoms can range widely, sometimes causing very mild illness and occasionally causing symptoms sufficiently severe to require hospitalization. In a patient presenting with symptoms that may result from acute retroviral syndrome, an HIV RNA test should be performed as it is the earliest indicator of HIV infection. It is critical that a patient suspected of having acute HIV be counseled regarding prevention of transmission since his or her infectivity during the initial infection is extremely high.

The latest US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) HIV guidelines, published in February 2013, recommend that all patients newly diagnosed with HIV be offered antiretroviral treatment.15 It is likely that earlier initiation of therapy will reduce the viral set point (the level of virus reached after an immune response to initial infection) and potentially reduce overall damage to the immune system.16 As with all HIV-positive patients, those with new infection must be prepared to commit to ongoing antiretroviral therapy, with the goal of achieving an undetectable viral load.

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING CHRONIC HIV

Most people with HIV infection will be asymptomatic up until approximately 10 years after the initial infection (hence the importance of screening), but some clinical symptoms and signs should bring HIV to mind as a possible cause. Persistent or recurrent fungal infections, especially oral thrush but also vaginal candidiasis, herpes zoster in an otherwise healthy patient, seborrheic dermatitis, unexplained weight loss, or persistent lymphadenopathy should trigger a suspicion of HIV during the differential diagnosis. Patients may also present very late in their HIV infection with far more serious opportunistic complications, including Pneumocystis jiroveci (formally carinii) pneumonia, infectious esophagitis, cryptococcal meningitis, tuberculosis, Kaposi sarcoma, or any of a myriad of other infectious or neoplastic complications of HIV-related immunosuppression. Most of these very serious illnesses will occur only in patients with a severely depressed immune system (CD4 < 200 cells/mm3), but some patients with very low CD4 cell counts may have no or only very mild symptoms.

Because improved screening has been shown to reduce the proportion of people presenting late in the course of HIV infection,17 patients presenting with severe manifestations of HIV-related immune dysfunction should become increasingly rare. Nonetheless, clinicians should include HIV in the differential for any patient presenting with a significant infection or cancer. A full discussion of HIV-related opportunistic infections and cancers is beyond the scope of this article, but further information can be found at www.aidsinfo.nih.gov.

On the next page: Initiating care >>

INITIATING CARE

Rapport is, of course, critical with all patients, but especially so in patients with HIV. The patient’s psychosocial as well as medical needs must be met in order to optimize adherence both to medication and to ongoing clinical care. HIV, even more than other life-changing chronic diseases, carries a stigma that patients can experience in a variety of ways. There are two messages that clinicians will want to convey to patients: HIV is a chronic, manageable condition, and support is available, either at the clinician’s office or through resources provided by the clinician upon diagnosis.

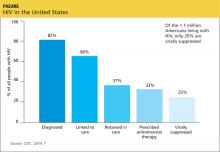

Underlying mental health problems, whether temporary or more chronic, can have a significant impact on the patient’s ability to adhere to the HIV treatment regimen. Addressing psychosocial needs may also help with patient adherence to clinical care. One of the most salient problems in HIV care today is retention in care. Only 25% of 1.1 million people living with HIV in the US are retained in care and achieve viral suppression (see Figure).18-20 Initial linkage to care and subsequent retention are areas in which all health care providers can play a role. Emergency and urgent care providers should have a protocol for immediate and direct referral of patients who test positive for HIV. Primary care providers can optimally treat their patients by closely monitoring response to therapy and reinforcing adherence to medication and to follow-up visits, both of which will substantially improve long-term survival.21,22

HIV treatment may begin as soon as the diagnosis is made and resistance test results become available, but the patient’s readiness to begin therapy is key. The patient needs to understand the chronic nature of the disease and the need for lifelong therapy so that he or she can commit to fully engaging in the management of the disease. While earlier HIV treatment improves the patient’s prognosis, the urgency of treatment increases gradually as the function of the immune system declines, particularly as the patient’s CD4 count drops below 350 cells/mm3.

The first step in managing a patient with HIV is to perform a complete history and physical examination. It must include a good family history; any concomitant medical conditions; current medications including herbal, alternative, and home therapies; and a complete social and behavioral history. Physical examination should be comprehensive, as manifestations of HIV may be subtle and can occur in any organ system. Physical manifestations of HIV are dependent on the patient’s immune status, but particular attention should be given to the skin and mucous membranes of the mouth and genitals as well as the neurologic examination. Neurologic complications of HIV may include sensory changes and cognitive dysfunction. Persistent nontender lymphadenopathy, which develops with initial infection, is frequently present. Of course, any clinical complaints should spur closer evaluation of the relevant system or systems.

Baseline laboratory testing should include confirmation of HIV if results were obtained anonymously or documentation is not available (Table 1). A resistance test (HIV genotype or GenoSure) should be performed at entry. Resistance mutations can be transmitted from person to person, and the baseline genotype offers the best opportunity to evaluate the patient for transmitted mutations. Resistance to a medication will determine antiretroviral therapy options for the patient. Hepatitis B and C status should be checked in all patients prior to starting therapy because results will impact therapeutic decisions. Patients co-infected with HIV and chronic hepatitis B should be evaluated by a specialist, since medication regimens for HIV and hepatitis B have overlapping activity against these viruses; it is generally advisable to fully treat both infections. Similarly, patients co-infected with hepatitis C and HIV should have a specialist consult. New advances in hepatitis C therapy are revolutionizing our approach to the disease, but HCV and HIV medications may have drug interactions.15,23

The most critical tests for evaluating the patient’s HIV status and response to therapy are the HIV RNA (viral load) and CD4 lymphocyte subset (also known as T cells, T4 cells, or CD4 cells). The CD4 count gives an estimate of the patient’s immune function, while the viral load is the best measure of the effect of medication. In general, the viral load should reach an undetectable level within the first few months of therapy. Other tests that should be done include chemistries and a urinalysis to evaluate renal function, liver enzymes, fasting lipids, and glucose (or A1C).

Other screening tests recommended at baseline include those for exposure to tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Additionally, all women with HIV should have a baseline cervical cancer screening. Cytomegalovirus infection may be assumed in men having sex with men or injection drug users, but a screening immunoglobulin G antibody test should be done in patients at lower risk. Patients without a history of varicella-zoster virus infection or vaccination should be screened for that disease and may be considered for vaccination if they are older than 8 years with a CD4 count higher than 200 or ages 1 to 8 with a CD4 percentage higher than 15%.15,24 Additionally, a test for the HLA-B*5701 allele is recommended prior to starting a regimen containing abacavir. Performing this test at baseline will allow the patient and clinician a broader set of treatment options if the test is negative.

Ongoing monitoring of a patient with HIV depends on many factors. Early in treatment, it is important to keep a regular schedule of visits to monitor continued response to therapy. Additionally, clinicians should monitor for complications of HIV and its treatment, including renal and hepatic effects. Some medications used in HIV therapy can alter laboratory parameters with or without an effect on function. For example, atazanavir will often increase levels of bilirubin. The change is generally mild and not associated with clinical effects. Similarly, elvitegravir and dolutegravir both cause an initial increase in serum creatinine that has not, to date, been associated with clinical renal disease.

The most significant complications faced by patients with HIV as they age are cardiac, metabolic, renal, and bone disease that tend to occur earlier and with greater severity than in the general population. HIV medications are associated with osteoporosis, lipid abnormalities, abnormal glucose metabolism, and renal toxicity. Older patients and those with personal or familial risk factors should be monitored for these complications according to standard prevention guidelines. The new primary care guidelines for the care of patients with HIV published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America acknowledge the far more manageable nature of HIV and extended lifespan of those with the disease. The guidelines recommend extending follow-up intervals to every six to 12 months for those who have no other health complication and whose viral load is undetectable

(< 20 copies/mL) for two to three years.15,24

All patients should receive standard vaccines, including influenza (annually), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis), and human papillomavirus (ages 9 to 26 for females and 9 to 21 for males). In addition, patients with HIV should receive a pneumococcal vaccine and, if antibody negative, a hepatitis A and/or B vaccine.

On the next page: Initiating antiretroviral therapy >>

INITIATING ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY

It is always helpful to consult an HIV expert prior to initiating antiretroviral therapy, but for patients with no baseline resistance, medical complications, or potential for drug interactions, initial therapy is fairly straightforward. The overall goals of therapy are to maximize the patient’s quality and quantity of life, improve immune function, suppress viral replication, and prevent HIV transmission.15 HIV transmission is significantly reduced when the infected patient is effectively treated and the viral load is suppressed to undetectable. Immune reconstitution as measured by the CD4 count is variable, but most patients will achieve some improvement once viral replication is controlled. Starting antiretroviral therapy is appropriate at any CD4 cell count level, but data regarding the need for therapy as the immune system is depleted are increasingly strong. The strongest data are for patients with CD4 counts below 350 cells/mm3, but large observational studies show benefit to patients starting earlier. There is also a public health benefit of reducing HIV transmission through treatment of patients already infected.25

Therapy cannot, at this time, eradicate the disease, but optimal viral suppression to an undetectable viral load is the most certain indication that therapy is working and should be monitored closely, generally every three or four months. The baseline viral load will respond quickly, and it is helpful to evaluate it shortly after initiating therapy. Scheduling a visit with the patient two weeks after initiating therapy offers the opportunity to perform a viral load test and to discuss any problems the patient has with therapy, including adherence, adverse effects, and any changes in concomitant medications. Alternately, the patient can be scheduled for an HIV RNA test at two weeks, with a clinical visit set for a time when results will be available (generally another week or two). Sharing viral load results is an excellent tool for supporting the patient’s self-efficacy. The dramatic reduction in virus helps both to assure the patient that he or she can successfully control HIV and to reinforce adherence to both medication and clinical follow-up.

Medication regimens for HIV have become increasingly easy to manage for both the patient and clinician. Most clinicians will generally use those listed as preferred regimens in the HHS guidelines (Table 2). Each recommended regimen contains three antiretroviral medications. Some also contain one additional medicine to pharmacologically boost the activity of one of the other medications by inhibiting metabolism. All recommended regimens include a backbone of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), with either a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, or a protease inhibitor (PI). All PIs and one of the recommended integrase inhibitor regimens will also include a boosting agent, either ritonavir or cobicistat.15,26

Four nucleoside backbone agents are among those listed as preferred: tenofovir, abacavir, emtricitabine, and lamivudine. Emtricitabine and lamivudine are nearly identical in action and should never be used together. Either may be combined with tenofovir or abacavir, but the availability of fixed-dose coformulations dictates that either tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada, also contained in Atripla and Complera, discussed below) or abacavir/lamivudine (Epzicom) is used in practice. Tenofovir is associated with renal toxicity and with osteoporosis. Abacavir is associated with a rare hypersensitivity reaction in patients with a positive HLA-B*5701 mutation. The only abacavir/lamivudine–containing regimen currently included as preferred in the HHS guidelines is with the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir, based on studies done with that combination. With the exception of abacavir, all these medications require an adjustment for patients with renal impairment.15

The one NNRTI-based regimen listed as preferred is a one-pill, once-daily combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine, coformulated under the trade name Atripla. The efavirenz component of this combination has some teratogenic potential and should generally not be used in women who are likely to become pregnant. Efavirenz has the potential to cause sleep disturbance and other central nervous system (CNS) effects; these often improve after a week or two of therapy. One additional consideration with an efavirenz-containing regimen is the long half-life of the drug relative to other components of the regimen. If a patient is inconsistently adherent, there will be periods when only efavirenz will remain in his or her system, leading to a high potential for the development of resistance. For this reason, it may not be the optimal initial choice for a patient who is known to have difficulty with medication adherence.15

There is another NNRTI-based regimen, a single-pill, once-daily coformulation that includes rilpivirine, tenofovir, and emtricitabine (Complera). It is currently included on the alternative, not the preferred, list of options, primarily because a high rate of virologic failure (failure to achieve an undetectable HIV RNA level) was seen in patients who started the regimen when their HIV RNA levels were greater than 100,000 copies/mL at baseline. In patients with lower HIV RNA levels at baseline, this regimen provides a reasonable alternative for women considering pregnancy or patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders or sleep disturbances, who are at particular risk for the CNS adverse effects of efavirenz. Like efavirenz, rilpivirine has also been associated with depressive disorders. It must be taken with a full meal (400 cal), so the patient’s eating pattern and access to food should be considered.

Two PI-based regimens are included as preferred: atazanavir and darunavir. Both must be boosted with a low dose (100 mg/d in a treatment-naïve patient) of ritonavir and combined with tenofovir/emtricitabine. While either regimen requires three separate pills daily, all three may be taken together along with food to improve absorption. As a class, boosted PIs provide a strong barrier to resistance and have a similar half-life to the NRTI backbone, making them a good choice for a patient with a history of medication nonadherence. The most common adverse reactions, particularly to the ritonavir portion of the regimen, are gastrointestinal disturbances, such as nausea and diarrhea. PIs are also associated with lipid abnormalities. This is less of a problem with atazanavir than with most other medications in the class. Atazanavir is associated with a benign increase in bilirubin that is generally asymptomatic. A coformulation of darunavir with tenofovir/emtricitabine and boosted with cobicistat rather than ritonavir is likely to be approved and available in the near future, providing the first one-pill, once-daily option for a PI-based regimen.

The newest class of HIV antiretroviral medications are the integrase strand transfer inhibitors: raltegravir, elvitegravir, and dolutegravir. Elvitegravir is available in a fixed-dose, one-pill, once-daily coformulation with tenofovir/emtricitabine and boosted with cobicistat. Raltegravir is currently dosed twice daily in combination with once daily tenofovir/etricitabine, but research on a once-daily formulation is in progress. Raltegravir is metabolized differently from most other medications used for HIV and may be better for use in patients on statins, opioids, oral contraceptives, and many other drugs. Dolutegravir is taken once daily with either tenofovir/emtricitabine or abacavir/lamivudine.15,26

A one-pill, once-daily coformulation of dolutegravir with abacavir/lamivudine will likely be available soon. Though most patients tolerate these drugs well, common adverse effects include nausea, diz-ziness, headache, and insomnia. Dolutegravir and elvitegravir will both cause an initial increase in the serum creatinine level, not associated with renal tubular dysfunction, that will stabilize after a few weeks.26

All preferred regimens are effective and should bring the viral load under control fairly rapidly, although full viral suppression may take weeks or months. Even after viral suppression is achieved, “blips” or temporary increases in the viral load can occur during therapy. However, a persistent viral load exceeding 200 copies/mL may indicate problems with the therapy. Clinicians should assess and reinforce adherence to the regimen, but if the viral load remains detectable, an expert should be

consulted.27

All medications used to control HIV have the potential for drug interactions, both with each other and with other commonly used medications, including OTC and herbal medicines. For this reason, it is important to carefully review all medicines for interactions; a full list may be found at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adoles cent-arv-guidelines/32/drug-interactions or www.hiv-druginteractions.org/.

On the next page: When to refer and conclusion >>

WHEN TO REFER

Expert assistance with initiation and management of HIV care is always helpful, but primary care clinicians can provide the majority of care. Obtain expert consultation when

• Initial resistance testing shows resistance to NRTI backbone medication(s) listed as preferred initial options

• There is a significant comorbidity, especially one that involves medications that may interact with an HIV regimen

• Hepatitis B or C is present

• Pregnancy is present or planned

• HIV is not controlled by the initial regimen or a regimen fails.

CONCLUSION

HIV is now viewed as a chronic, manageable disease. As improved screening continues to identify an increasing proportion of HIV-positive patients, improving therapies keep these patients alive and well. As access to care continues to improve, primary care clinicians will provide more of the care of HIV patients. Some patients will require consultation with an HIV specialist, but primary care clinicians must build a strong foundation of knowledge regarding the treatment of HIV and remain current as progress in the field continues.

1. Daar ES, Little S, Pitt J, et al. Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection: Los Angeles county primary HIV infection recruitment network. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:25-29.

2. Hightow-Weidman LB, Golin CE, Green K, et al. Identifying people with acute HIV infection: demographic features, risk factors, and use of health care among individuals with AHI in North Carolina. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1075-1083.

3. Richey LE, Halperin J. Acute human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(2):136-142.

4. Weintraub AC, Giner J, Menezes P, et al. Infrequent diagnosis of primary human immunodeficiency virus infection: missed opportunities in acute care settings. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2097-2100.

5. Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446-453.

6. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resourc es/reports/#supplemental. Accessed April 15, 2014.

7. CDC. National HIV prevention progress report, 2013. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NationalProgressReport.pdf. Published December 2013. Accessed April 15, 2014.

8. CDC. Draft recommendations: diagnostic laboratory testing for HIV infection in the United States. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_Draft_HIV_Testing_Alg_Rec_508.2.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2014.

9. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:875-892.

10. Pinkerton SD, Martin JN, Roland ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV postexposure prophylaxis following sexual or injection drug exposure in 96 metropolitan areas in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18:2065-2073.

11. CDC. Update to interim guidance for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the prevention of HIV infection: PrEP for injecting drug users. MMWR. 2013;62:463-465.

12. Bell DM. Occupational risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: an overview. Am J Med. 1997;102(suppl 5B):9-15.

13. CDC. Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR. 2012;61:586-589.

14. CDC. Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR. 2011;60:65-68.

15. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2014.

16. Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1815-1826.

17. Castel AD, Magnus M, Peterson J, et al. Implementing a novel citywide rapid HIV testing campaign in Washington, DC: findings and lessons learned. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:422-431.

18. CDC. HIV in the United States: stages of care. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research_mmp_StagesofCare.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2014.

19. Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793-800.

20. Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. Retention in Care (RIC) Study Group. Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:574-580.

21. Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, et al. Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:249-259.

22. Rebeiro P, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, et al. Retention among North American HIV-infected persons in clinical care, 2000-2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:356-362.

23. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org/. Accessed April 15, 2014.

24. Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e1-e34.

25. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493-505.

26. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Recommendation on integrase inhibitor use in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals from the HHS panel on antiretroviral guidelines for adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/upload/AdultARV_INSTIRecommendations.pdf. Updated 2013. Accessed April 15, 2014.

27. Chesney MA. The elusive gold standard: future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(suppl 1):S149-155.

CE/CME No: CR-1405

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the current recommendations for HIV screening.

• Describe the current recommendations for pre- and postexposure HIV prophylaxis.

• Recognize the constellation of symptoms and signs that may represent a patient presenting with acute (primary) HIV infection.

• Discuss the initial evaluation and management of a patient with HIV.

• Compare and contrast the preferred regimens for previously untreated patients with HIV in terms of the key features of the regimens’ components and the rationale for using one versus another.

FACULTY

Susan LeLacheur is an Associate Professor of PA Studies at The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, DC.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.5 hours of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category I CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of May 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

Over the decades, HIV infection has transitioned from an almost universally deadly infection to a chronic, manageable disease. Increased survival, along with improved access to health care and screening, has allowed far more patients to live relatively normal lives. But primary care providers need to stay up to date on all aspects of the disease in order to provide the best possible care to those affected and aid efforts to stem the spread of disease.

Patients with HIV infection whose disease is well controlled can now live a normal lifespan. Because of this increase in lifespan, along with increased health care coverage through the Affordable Care Act, primary care clinicians will be increasingly responsible for the care of patients with HIV. In order to offer optimal treatment, however, clinicians must remain current on HIV screening, initial treatment, and ongoing management. New therapies and simplified regimens have improved HIV care, but diligence in monitoring for complications of HIV and its treatment is needed in order to optimize care.

Consider, for example, a 19-year-old man who comes into your primary care office complaining of a sore throat, malaise, and a generalized rash. On exam, you note cervical adenopathy and a widely scattered rash, mainly on his trunk. His throat is mildly erythematous without exudates. You do a rapid test for strep and for mononucleosis, both of which are negative. A viral syndrome seems the most likely diagnosis, but if you neglect to get a sexual and drug history, you might not think of HIV as the virus in question. And even if routine HIV antibody screening is done as recommended, HIV antibodies have likely not yet developed. This is a classic presentation of acute retroviral syndrome, easily confused with a myriad of less consequential infections. Most cases of HIV are not detected at this stage, although it is estimated that between 50% and 90% of patients with acute HIV infection seek medical care.1-4 The patient with acute HIV and potentially many others can be spared significant harm if HIV is part of your differential diagnosis.

Primary care clinicians play a key role in all aspects of HIV care, starting with HIV prevention through screening, helping HIV-negative patients reduce the risk for infection, and helping to assure that HIV-positive patients are less likely to spread the disease because their own infection is fully suppressed. Primary care providers will also become increasingly involved in the care of patients who are living with HIV. Just as with diabetes or hypertension, patients already HIV infected can be largely managed by knowledgeable primary care clinicians. The required knowledge includes an understanding of the latest recommendations for screening, both pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis, and the initial work-up and ongoing management of patients diagnosed with HIV. Expert consultation is often helpful and will be critical in many cases, but all providers should have a working knowledge of HIV care.

On the next page: Screening and prevention >>

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

When discussing many disease processes, prevention is relegated to the end of the discussion—but with HIV, prevention must be a primary concern for patients and providers. HIV prevention includes two critical strategies: finding previously undiagnosed cases of the infection and preventing transmission through treatment of those with the disease, safer sex practices, or prophylactic antiretroviral therapy for those at highest risk. (Chemoprophylaxis for those who have had a potential exposure is referred to as postexposure prophylaxis, or PEP. Chemoprophylaxis for those at high risk for exposure is termed pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.)

Guidelines published by the CDC in 2006 recommended that clinicians include HIV screening as a routine part of medical care for all patients and that barriers to routine HIV testing be removed. Since then, the estimated proportion of people infected with HIV who are unaware of their HIV-positive status has dropped from about 25% to 16%.5-7 In applying these recommendations to a primary care setting, the practitioner simply adds an HIV antibody test to the standard panel given to new patients. In addition, established patients who have not previously been tested should be advised to have a baseline HIV test regardless of risk.

Clinicians should offer HIV testing on an opt-out basis and inform patients that the test is recommended; patients can refuse the test should they choose to do so. Patients at higher risk for HIV should undergo retesting annually—or more frequently if indicated. Routine testing need not be accompanied by prevention counseling or special consent. While counseling on safer sex or other risk reduction strategies is always appropriate, it should not be seen as an impediment to routine screening.

Newer fourth-generation immunofluorescence assays (IA) detect both HIV-1 and HIV-2 earlier after infection because they are able to detect the HIV viral capsid protein p24 as well as HIV antibodies. If the initial assay is positive, subsequent confirmatory testing with a discrimination assay will distinguish between the two types of HIV. Because the newer IA tests detect antibody much earlier, using the discrimination assay as the confirmatory test rather than a Western blot has become commonplace, although either test may be used. Home testing for HIV is also available. Patients who obtain a positive result are instructed to have the result confirmed by their health care provider.

Neither rapid tests nor home tests will pick up new infections during initial infection (known as the window period prior to the development of detectable antibodies) but they can be very helpful in screening programs since the patient need not return for a second visit to obtain results. Whatever test is initially used, it is important to confirm its results with a second test; for instance, the first test might be a fourth-generation IA (either a rapid test or traditional), confirmed by a discrimination assay or Western blot. If the confirmatory test is negative or indeterminate, an HIV RNA (viral load) test should be considered.8 HIV RNA should also be used whenever a new infection is suspected.

PRE- AND POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

PEP to prevent HIV seroconversion following a possible or confirmed HIV exposure is now well accepted, whether the exposure is occupational or not.9,10 Clinicians should start PEP as soon as possible after exposure, preferably within two hours, but no later than 72 hours after exposure. Do not delay treatment even if the source's or exposed patient’s HIV status or other factors are unknown. Treatment can always be discontinued or modified when further information becomes available.

The most recent update issued by the US Public Health Service includes a change to prior guidelines. They now recommend that all potentially exposed individuals receive a three-drug combination of tenofovir 300 mg orally once daily, emtricitabine 200 mg orally once daily (coformulated as Truvada), and raltegravir 400 mg orally twice daily. Patients should be instructed to continue antiretroviral medications for four weeks. Raltegravir, an integrase inhibitor, has replaced previously recommended drugs used in a three-drug regimen because of its lower incidence of adverse effects as compared to older antiretrovirals. Alternative regimens may be used for a variety of reasons, but the need for an alternative should generally spur expert consultation.

The use of three drugs in all cases is based both on a better understanding of the pathophysiology of HIV and on the availability of medications that are better tolerated. Expert consultation is always helpful in cases of PEP, but particularly in those complicated by pregnancy or breastfeeding, known or suspected drug resistance in the source patient, unknown HIV status of the source patient, delayed report of exposure (> 72 hours), or significant medical illness of the exposed patient. In addition, any toxicity experienced should spur expert consultation. If local expert resources are unavailable, immediate assistance can be obtained through the National Clinicians' Postexposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at (888) 448-4911.

Whenever possible, the source patient should undergo testing if his or her HIV status is unknown. If the exposed patient chooses to receive PEP, it is helpful to evaluate the source patient’s history of medication resistance, which should be done by a clinician with HIV expertise. In all cases, the likelihood of HIV conversion after an exposure is low, ranging from approximately 0.3% for a percutaneous exposure to 0.09% for a mucous membrane exposure.11,12

Clinicians should test the exposed patient for HIV and hepatitis B and C, and women should have a pregnancy test performed. For patients being treated, renal and hepatic function should be evaluated and hematology tests done to monitor for adverse reactions to therapy at baseline, two weeks, and completion of treatment. The exposed patient must be advised to take precautions to avoid any potential for transmission of HIV: use barrier contraception and avoid blood or tissue donation or breastfeeding until after the final follow-up visit. Initial follow-up should occur within 72 hours to reevaluate the need for therapy and reinforce the need for adherence if therapy is continued. Clinicians should also assess the patient regarding his or her emotional as well as physical well-being and access to resources to aid in coping with the event. If a fourth-generation test is used, follow-up HIV testing should be done at six weeks and four months after exposure. Otherwise, follow-up HIV testing should occur at six weeks, 12 weeks, and six months.

PrEP using tenofovir 300 mg orally once daily and emtricitabine 200 mg orally once daily is recommended in interim CDC guidelines for those at particularly high risk for HIV exposure, such as homosexual or heterosexual partners of HIV-positive individuals or injection drug users. For PrEP to be effective, medication adherence is critical. Because PrEP involves daily therapy, patients should be carefully selected and expert consultation is advised.13,14 All patients on PrEP require regular follow-up and HIV testing. On follow-up, side effects and continued risk should be evaluated. PrEP should be considered part of a broader prevention strategy that includes condom use, prevention and treatment of other sexually transmitted infections, and frequent reassessment of risk. There are often significant difficulties in obtaining insurance coverage for PrEP, but this may change as further research is done and health care coverage broadens.

On the next page: Recognizing and managing acute HIV >>

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING ACUTE HIV

As noted above, the symptoms of acute (or primary) retroviral syndrome can suggest numerous other infectious processes, including mononucleosis, influenza, or the common cold. The most common symptoms are fever, fatigue, and malaise, but arthralgias, headache, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, and pharyngitis are also common. The severity of symptoms can range widely, sometimes causing very mild illness and occasionally causing symptoms sufficiently severe to require hospitalization. In a patient presenting with symptoms that may result from acute retroviral syndrome, an HIV RNA test should be performed as it is the earliest indicator of HIV infection. It is critical that a patient suspected of having acute HIV be counseled regarding prevention of transmission since his or her infectivity during the initial infection is extremely high.

The latest US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) HIV guidelines, published in February 2013, recommend that all patients newly diagnosed with HIV be offered antiretroviral treatment.15 It is likely that earlier initiation of therapy will reduce the viral set point (the level of virus reached after an immune response to initial infection) and potentially reduce overall damage to the immune system.16 As with all HIV-positive patients, those with new infection must be prepared to commit to ongoing antiretroviral therapy, with the goal of achieving an undetectable viral load.

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING CHRONIC HIV

Most people with HIV infection will be asymptomatic up until approximately 10 years after the initial infection (hence the importance of screening), but some clinical symptoms and signs should bring HIV to mind as a possible cause. Persistent or recurrent fungal infections, especially oral thrush but also vaginal candidiasis, herpes zoster in an otherwise healthy patient, seborrheic dermatitis, unexplained weight loss, or persistent lymphadenopathy should trigger a suspicion of HIV during the differential diagnosis. Patients may also present very late in their HIV infection with far more serious opportunistic complications, including Pneumocystis jiroveci (formally carinii) pneumonia, infectious esophagitis, cryptococcal meningitis, tuberculosis, Kaposi sarcoma, or any of a myriad of other infectious or neoplastic complications of HIV-related immunosuppression. Most of these very serious illnesses will occur only in patients with a severely depressed immune system (CD4 < 200 cells/mm3), but some patients with very low CD4 cell counts may have no or only very mild symptoms.

Because improved screening has been shown to reduce the proportion of people presenting late in the course of HIV infection,17 patients presenting with severe manifestations of HIV-related immune dysfunction should become increasingly rare. Nonetheless, clinicians should include HIV in the differential for any patient presenting with a significant infection or cancer. A full discussion of HIV-related opportunistic infections and cancers is beyond the scope of this article, but further information can be found at www.aidsinfo.nih.gov.

On the next page: Initiating care >>

INITIATING CARE

Rapport is, of course, critical with all patients, but especially so in patients with HIV. The patient’s psychosocial as well as medical needs must be met in order to optimize adherence both to medication and to ongoing clinical care. HIV, even more than other life-changing chronic diseases, carries a stigma that patients can experience in a variety of ways. There are two messages that clinicians will want to convey to patients: HIV is a chronic, manageable condition, and support is available, either at the clinician’s office or through resources provided by the clinician upon diagnosis.

Underlying mental health problems, whether temporary or more chronic, can have a significant impact on the patient’s ability to adhere to the HIV treatment regimen. Addressing psychosocial needs may also help with patient adherence to clinical care. One of the most salient problems in HIV care today is retention in care. Only 25% of 1.1 million people living with HIV in the US are retained in care and achieve viral suppression (see Figure).18-20 Initial linkage to care and subsequent retention are areas in which all health care providers can play a role. Emergency and urgent care providers should have a protocol for immediate and direct referral of patients who test positive for HIV. Primary care providers can optimally treat their patients by closely monitoring response to therapy and reinforcing adherence to medication and to follow-up visits, both of which will substantially improve long-term survival.21,22

HIV treatment may begin as soon as the diagnosis is made and resistance test results become available, but the patient’s readiness to begin therapy is key. The patient needs to understand the chronic nature of the disease and the need for lifelong therapy so that he or she can commit to fully engaging in the management of the disease. While earlier HIV treatment improves the patient’s prognosis, the urgency of treatment increases gradually as the function of the immune system declines, particularly as the patient’s CD4 count drops below 350 cells/mm3.

The first step in managing a patient with HIV is to perform a complete history and physical examination. It must include a good family history; any concomitant medical conditions; current medications including herbal, alternative, and home therapies; and a complete social and behavioral history. Physical examination should be comprehensive, as manifestations of HIV may be subtle and can occur in any organ system. Physical manifestations of HIV are dependent on the patient’s immune status, but particular attention should be given to the skin and mucous membranes of the mouth and genitals as well as the neurologic examination. Neurologic complications of HIV may include sensory changes and cognitive dysfunction. Persistent nontender lymphadenopathy, which develops with initial infection, is frequently present. Of course, any clinical complaints should spur closer evaluation of the relevant system or systems.

Baseline laboratory testing should include confirmation of HIV if results were obtained anonymously or documentation is not available (Table 1). A resistance test (HIV genotype or GenoSure) should be performed at entry. Resistance mutations can be transmitted from person to person, and the baseline genotype offers the best opportunity to evaluate the patient for transmitted mutations. Resistance to a medication will determine antiretroviral therapy options for the patient. Hepatitis B and C status should be checked in all patients prior to starting therapy because results will impact therapeutic decisions. Patients co-infected with HIV and chronic hepatitis B should be evaluated by a specialist, since medication regimens for HIV and hepatitis B have overlapping activity against these viruses; it is generally advisable to fully treat both infections. Similarly, patients co-infected with hepatitis C and HIV should have a specialist consult. New advances in hepatitis C therapy are revolutionizing our approach to the disease, but HCV and HIV medications may have drug interactions.15,23

The most critical tests for evaluating the patient’s HIV status and response to therapy are the HIV RNA (viral load) and CD4 lymphocyte subset (also known as T cells, T4 cells, or CD4 cells). The CD4 count gives an estimate of the patient’s immune function, while the viral load is the best measure of the effect of medication. In general, the viral load should reach an undetectable level within the first few months of therapy. Other tests that should be done include chemistries and a urinalysis to evaluate renal function, liver enzymes, fasting lipids, and glucose (or A1C).

Other screening tests recommended at baseline include those for exposure to tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Additionally, all women with HIV should have a baseline cervical cancer screening. Cytomegalovirus infection may be assumed in men having sex with men or injection drug users, but a screening immunoglobulin G antibody test should be done in patients at lower risk. Patients without a history of varicella-zoster virus infection or vaccination should be screened for that disease and may be considered for vaccination if they are older than 8 years with a CD4 count higher than 200 or ages 1 to 8 with a CD4 percentage higher than 15%.15,24 Additionally, a test for the HLA-B*5701 allele is recommended prior to starting a regimen containing abacavir. Performing this test at baseline will allow the patient and clinician a broader set of treatment options if the test is negative.

Ongoing monitoring of a patient with HIV depends on many factors. Early in treatment, it is important to keep a regular schedule of visits to monitor continued response to therapy. Additionally, clinicians should monitor for complications of HIV and its treatment, including renal and hepatic effects. Some medications used in HIV therapy can alter laboratory parameters with or without an effect on function. For example, atazanavir will often increase levels of bilirubin. The change is generally mild and not associated with clinical effects. Similarly, elvitegravir and dolutegravir both cause an initial increase in serum creatinine that has not, to date, been associated with clinical renal disease.

The most significant complications faced by patients with HIV as they age are cardiac, metabolic, renal, and bone disease that tend to occur earlier and with greater severity than in the general population. HIV medications are associated with osteoporosis, lipid abnormalities, abnormal glucose metabolism, and renal toxicity. Older patients and those with personal or familial risk factors should be monitored for these complications according to standard prevention guidelines. The new primary care guidelines for the care of patients with HIV published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America acknowledge the far more manageable nature of HIV and extended lifespan of those with the disease. The guidelines recommend extending follow-up intervals to every six to 12 months for those who have no other health complication and whose viral load is undetectable

(< 20 copies/mL) for two to three years.15,24

All patients should receive standard vaccines, including influenza (annually), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis), and human papillomavirus (ages 9 to 26 for females and 9 to 21 for males). In addition, patients with HIV should receive a pneumococcal vaccine and, if antibody negative, a hepatitis A and/or B vaccine.

On the next page: Initiating antiretroviral therapy >>

INITIATING ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY

It is always helpful to consult an HIV expert prior to initiating antiretroviral therapy, but for patients with no baseline resistance, medical complications, or potential for drug interactions, initial therapy is fairly straightforward. The overall goals of therapy are to maximize the patient’s quality and quantity of life, improve immune function, suppress viral replication, and prevent HIV transmission.15 HIV transmission is significantly reduced when the infected patient is effectively treated and the viral load is suppressed to undetectable. Immune reconstitution as measured by the CD4 count is variable, but most patients will achieve some improvement once viral replication is controlled. Starting antiretroviral therapy is appropriate at any CD4 cell count level, but data regarding the need for therapy as the immune system is depleted are increasingly strong. The strongest data are for patients with CD4 counts below 350 cells/mm3, but large observational studies show benefit to patients starting earlier. There is also a public health benefit of reducing HIV transmission through treatment of patients already infected.25

Therapy cannot, at this time, eradicate the disease, but optimal viral suppression to an undetectable viral load is the most certain indication that therapy is working and should be monitored closely, generally every three or four months. The baseline viral load will respond quickly, and it is helpful to evaluate it shortly after initiating therapy. Scheduling a visit with the patient two weeks after initiating therapy offers the opportunity to perform a viral load test and to discuss any problems the patient has with therapy, including adherence, adverse effects, and any changes in concomitant medications. Alternately, the patient can be scheduled for an HIV RNA test at two weeks, with a clinical visit set for a time when results will be available (generally another week or two). Sharing viral load results is an excellent tool for supporting the patient’s self-efficacy. The dramatic reduction in virus helps both to assure the patient that he or she can successfully control HIV and to reinforce adherence to both medication and clinical follow-up.

Medication regimens for HIV have become increasingly easy to manage for both the patient and clinician. Most clinicians will generally use those listed as preferred regimens in the HHS guidelines (Table 2). Each recommended regimen contains three antiretroviral medications. Some also contain one additional medicine to pharmacologically boost the activity of one of the other medications by inhibiting metabolism. All recommended regimens include a backbone of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), with either a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, or a protease inhibitor (PI). All PIs and one of the recommended integrase inhibitor regimens will also include a boosting agent, either ritonavir or cobicistat.15,26

Four nucleoside backbone agents are among those listed as preferred: tenofovir, abacavir, emtricitabine, and lamivudine. Emtricitabine and lamivudine are nearly identical in action and should never be used together. Either may be combined with tenofovir or abacavir, but the availability of fixed-dose coformulations dictates that either tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada, also contained in Atripla and Complera, discussed below) or abacavir/lamivudine (Epzicom) is used in practice. Tenofovir is associated with renal toxicity and with osteoporosis. Abacavir is associated with a rare hypersensitivity reaction in patients with a positive HLA-B*5701 mutation. The only abacavir/lamivudine–containing regimen currently included as preferred in the HHS guidelines is with the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir, based on studies done with that combination. With the exception of abacavir, all these medications require an adjustment for patients with renal impairment.15

The one NNRTI-based regimen listed as preferred is a one-pill, once-daily combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine, coformulated under the trade name Atripla. The efavirenz component of this combination has some teratogenic potential and should generally not be used in women who are likely to become pregnant. Efavirenz has the potential to cause sleep disturbance and other central nervous system (CNS) effects; these often improve after a week or two of therapy. One additional consideration with an efavirenz-containing regimen is the long half-life of the drug relative to other components of the regimen. If a patient is inconsistently adherent, there will be periods when only efavirenz will remain in his or her system, leading to a high potential for the development of resistance. For this reason, it may not be the optimal initial choice for a patient who is known to have difficulty with medication adherence.15

There is another NNRTI-based regimen, a single-pill, once-daily coformulation that includes rilpivirine, tenofovir, and emtricitabine (Complera). It is currently included on the alternative, not the preferred, list of options, primarily because a high rate of virologic failure (failure to achieve an undetectable HIV RNA level) was seen in patients who started the regimen when their HIV RNA levels were greater than 100,000 copies/mL at baseline. In patients with lower HIV RNA levels at baseline, this regimen provides a reasonable alternative for women considering pregnancy or patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders or sleep disturbances, who are at particular risk for the CNS adverse effects of efavirenz. Like efavirenz, rilpivirine has also been associated with depressive disorders. It must be taken with a full meal (400 cal), so the patient’s eating pattern and access to food should be considered.

Two PI-based regimens are included as preferred: atazanavir and darunavir. Both must be boosted with a low dose (100 mg/d in a treatment-naïve patient) of ritonavir and combined with tenofovir/emtricitabine. While either regimen requires three separate pills daily, all three may be taken together along with food to improve absorption. As a class, boosted PIs provide a strong barrier to resistance and have a similar half-life to the NRTI backbone, making them a good choice for a patient with a history of medication nonadherence. The most common adverse reactions, particularly to the ritonavir portion of the regimen, are gastrointestinal disturbances, such as nausea and diarrhea. PIs are also associated with lipid abnormalities. This is less of a problem with atazanavir than with most other medications in the class. Atazanavir is associated with a benign increase in bilirubin that is generally asymptomatic. A coformulation of darunavir with tenofovir/emtricitabine and boosted with cobicistat rather than ritonavir is likely to be approved and available in the near future, providing the first one-pill, once-daily option for a PI-based regimen.

The newest class of HIV antiretroviral medications are the integrase strand transfer inhibitors: raltegravir, elvitegravir, and dolutegravir. Elvitegravir is available in a fixed-dose, one-pill, once-daily coformulation with tenofovir/emtricitabine and boosted with cobicistat. Raltegravir is currently dosed twice daily in combination with once daily tenofovir/etricitabine, but research on a once-daily formulation is in progress. Raltegravir is metabolized differently from most other medications used for HIV and may be better for use in patients on statins, opioids, oral contraceptives, and many other drugs. Dolutegravir is taken once daily with either tenofovir/emtricitabine or abacavir/lamivudine.15,26

A one-pill, once-daily coformulation of dolutegravir with abacavir/lamivudine will likely be available soon. Though most patients tolerate these drugs well, common adverse effects include nausea, diz-ziness, headache, and insomnia. Dolutegravir and elvitegravir will both cause an initial increase in the serum creatinine level, not associated with renal tubular dysfunction, that will stabilize after a few weeks.26

All preferred regimens are effective and should bring the viral load under control fairly rapidly, although full viral suppression may take weeks or months. Even after viral suppression is achieved, “blips” or temporary increases in the viral load can occur during therapy. However, a persistent viral load exceeding 200 copies/mL may indicate problems with the therapy. Clinicians should assess and reinforce adherence to the regimen, but if the viral load remains detectable, an expert should be

consulted.27

All medications used to control HIV have the potential for drug interactions, both with each other and with other commonly used medications, including OTC and herbal medicines. For this reason, it is important to carefully review all medicines for interactions; a full list may be found at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adoles cent-arv-guidelines/32/drug-interactions or www.hiv-druginteractions.org/.

On the next page: When to refer and conclusion >>

WHEN TO REFER

Expert assistance with initiation and management of HIV care is always helpful, but primary care clinicians can provide the majority of care. Obtain expert consultation when

• Initial resistance testing shows resistance to NRTI backbone medication(s) listed as preferred initial options

• There is a significant comorbidity, especially one that involves medications that may interact with an HIV regimen

• Hepatitis B or C is present

• Pregnancy is present or planned

• HIV is not controlled by the initial regimen or a regimen fails.

CONCLUSION

HIV is now viewed as a chronic, manageable disease. As improved screening continues to identify an increasing proportion of HIV-positive patients, improving therapies keep these patients alive and well. As access to care continues to improve, primary care clinicians will provide more of the care of HIV patients. Some patients will require consultation with an HIV specialist, but primary care clinicians must build a strong foundation of knowledge regarding the treatment of HIV and remain current as progress in the field continues.

CE/CME No: CR-1405

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the current recommendations for HIV screening.

• Describe the current recommendations for pre- and postexposure HIV prophylaxis.

• Recognize the constellation of symptoms and signs that may represent a patient presenting with acute (primary) HIV infection.

• Discuss the initial evaluation and management of a patient with HIV.

• Compare and contrast the preferred regimens for previously untreated patients with HIV in terms of the key features of the regimens’ components and the rationale for using one versus another.

FACULTY

Susan LeLacheur is an Associate Professor of PA Studies at The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, DC.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.5 hours of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category I CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of May 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

Over the decades, HIV infection has transitioned from an almost universally deadly infection to a chronic, manageable disease. Increased survival, along with improved access to health care and screening, has allowed far more patients to live relatively normal lives. But primary care providers need to stay up to date on all aspects of the disease in order to provide the best possible care to those affected and aid efforts to stem the spread of disease.

Patients with HIV infection whose disease is well controlled can now live a normal lifespan. Because of this increase in lifespan, along with increased health care coverage through the Affordable Care Act, primary care clinicians will be increasingly responsible for the care of patients with HIV. In order to offer optimal treatment, however, clinicians must remain current on HIV screening, initial treatment, and ongoing management. New therapies and simplified regimens have improved HIV care, but diligence in monitoring for complications of HIV and its treatment is needed in order to optimize care.

Consider, for example, a 19-year-old man who comes into your primary care office complaining of a sore throat, malaise, and a generalized rash. On exam, you note cervical adenopathy and a widely scattered rash, mainly on his trunk. His throat is mildly erythematous without exudates. You do a rapid test for strep and for mononucleosis, both of which are negative. A viral syndrome seems the most likely diagnosis, but if you neglect to get a sexual and drug history, you might not think of HIV as the virus in question. And even if routine HIV antibody screening is done as recommended, HIV antibodies have likely not yet developed. This is a classic presentation of acute retroviral syndrome, easily confused with a myriad of less consequential infections. Most cases of HIV are not detected at this stage, although it is estimated that between 50% and 90% of patients with acute HIV infection seek medical care.1-4 The patient with acute HIV and potentially many others can be spared significant harm if HIV is part of your differential diagnosis.

Primary care clinicians play a key role in all aspects of HIV care, starting with HIV prevention through screening, helping HIV-negative patients reduce the risk for infection, and helping to assure that HIV-positive patients are less likely to spread the disease because their own infection is fully suppressed. Primary care providers will also become increasingly involved in the care of patients who are living with HIV. Just as with diabetes or hypertension, patients already HIV infected can be largely managed by knowledgeable primary care clinicians. The required knowledge includes an understanding of the latest recommendations for screening, both pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis, and the initial work-up and ongoing management of patients diagnosed with HIV. Expert consultation is often helpful and will be critical in many cases, but all providers should have a working knowledge of HIV care.

On the next page: Screening and prevention >>

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

When discussing many disease processes, prevention is relegated to the end of the discussion—but with HIV, prevention must be a primary concern for patients and providers. HIV prevention includes two critical strategies: finding previously undiagnosed cases of the infection and preventing transmission through treatment of those with the disease, safer sex practices, or prophylactic antiretroviral therapy for those at highest risk. (Chemoprophylaxis for those who have had a potential exposure is referred to as postexposure prophylaxis, or PEP. Chemoprophylaxis for those at high risk for exposure is termed pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.)

Guidelines published by the CDC in 2006 recommended that clinicians include HIV screening as a routine part of medical care for all patients and that barriers to routine HIV testing be removed. Since then, the estimated proportion of people infected with HIV who are unaware of their HIV-positive status has dropped from about 25% to 16%.5-7 In applying these recommendations to a primary care setting, the practitioner simply adds an HIV antibody test to the standard panel given to new patients. In addition, established patients who have not previously been tested should be advised to have a baseline HIV test regardless of risk.

Clinicians should offer HIV testing on an opt-out basis and inform patients that the test is recommended; patients can refuse the test should they choose to do so. Patients at higher risk for HIV should undergo retesting annually—or more frequently if indicated. Routine testing need not be accompanied by prevention counseling or special consent. While counseling on safer sex or other risk reduction strategies is always appropriate, it should not be seen as an impediment to routine screening.

Newer fourth-generation immunofluorescence assays (IA) detect both HIV-1 and HIV-2 earlier after infection because they are able to detect the HIV viral capsid protein p24 as well as HIV antibodies. If the initial assay is positive, subsequent confirmatory testing with a discrimination assay will distinguish between the two types of HIV. Because the newer IA tests detect antibody much earlier, using the discrimination assay as the confirmatory test rather than a Western blot has become commonplace, although either test may be used. Home testing for HIV is also available. Patients who obtain a positive result are instructed to have the result confirmed by their health care provider.