User login

What effects—if any—does marijuana use during pregnancy have on the fetus or child?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

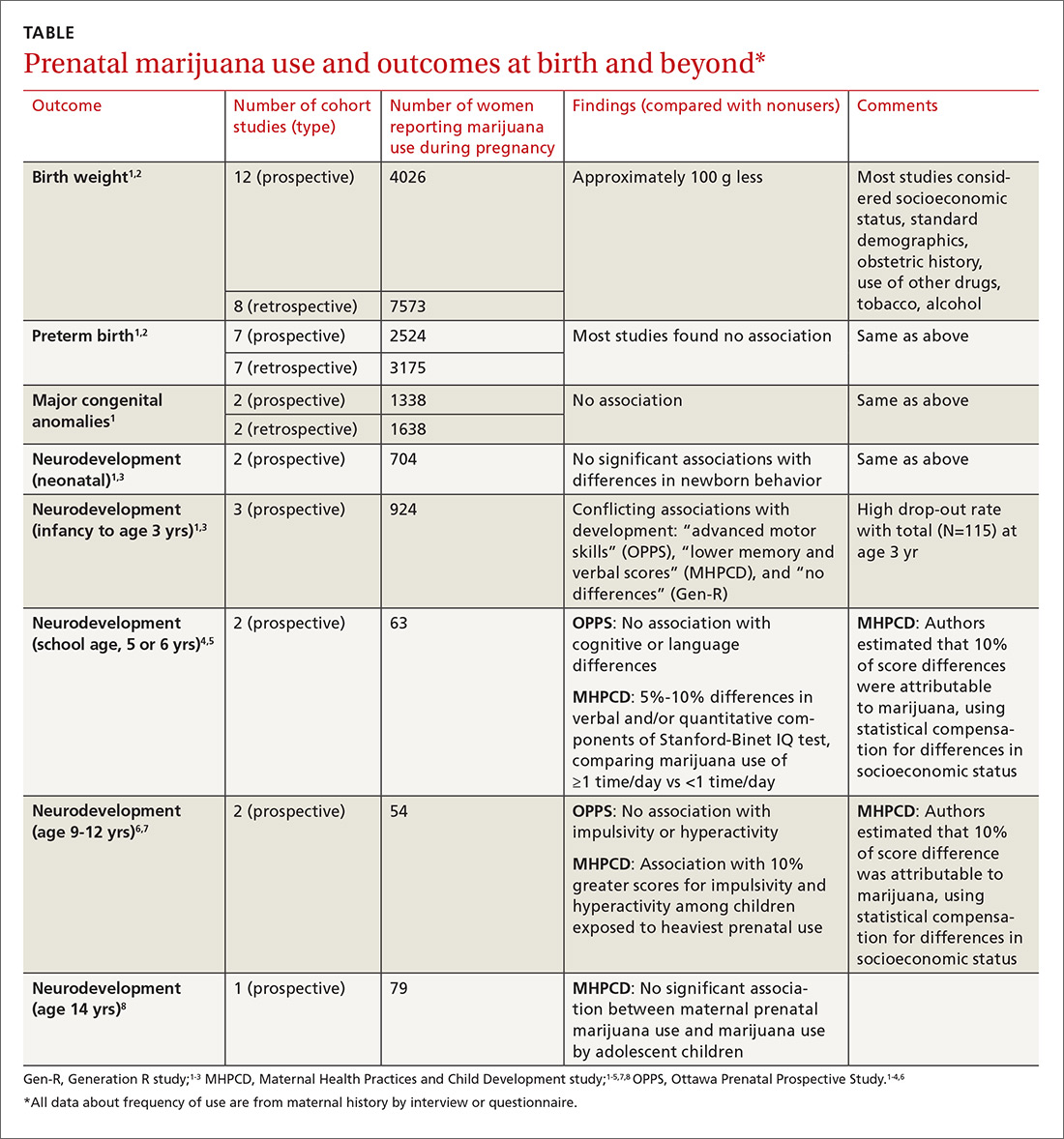

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A large systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies found little or no effect of maternal marijuana use on birth weight, stillbirths, preterm births, or congenital anomalies (TABLE1-8). Some studies found lower birth weights and some found higher birth weights. The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity, but estimated a clinically insignificant difference of 100 g. Most studies were limited by failure to account for concurrent maternal tobacco smoking.

Moreover, all studies used interview data to determine maternal prenatal marijuana use, which can be subject to large recall bias. A multicenter prospective study of 585 pregnant women that compared interview data with serum screening to identify tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) found poor correlation between history and laboratory validation, for example.1 Only 31% of pregnant women with positive THC testing self-reported marijuana use (31% sensitivity), and only 43% of women who reported marijuana use had a positive THC screen (43% specificity). Most studies didn’t quantify marijuana use well and didn’t associate use with trimester of exposure.

The authors also point out that marijuana potency has increased substantially since the 1980s when many of the studies were done (THC content was 3.2% in 1983 and 13% in 2008); prenatal marijuana use in the present day may expose the fetus to larger amounts of THC.1

A 2016 retrospective cohort study of 56 mothers who reported prenatal marijuana use found no differences in preterm birth, low birth weight, or Apgar scores.2

Neurodevelopmental effects on infants, long-term effects on children, teens

Three prospective cohort studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates and infants, and 2 studies continued to follow children into adolescence.1,3 All found essentially no differences associated with prenatal marijuana at birth, throughout infancy, and through age 3 years. The studies had the same limitations as those described previously (potential recall bias for identifying which children were exposed to marijuana prenatally and poorly quantified marijuana use not well-associated with trimester of exposure).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS) examined 140 low-risk pregnancies in white women of higher socioeconomic status who used marijuana during pregnancy.1,3-7 Investigators considered: socioeconomic status, standard demographics, obstetric history, and use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Using a standardized newborn assessment scale, they found subtle behavioral differences at one week but not 9 days. Investigators evaluated children again at 3 years of age, school entry (5 or 6 years), and 9 to 12 years.

The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development study (MHPCD) of 564 high-risk pregnancies in predominantly minority women of low socioeconomic status followed infants from birth through 14 years of age.1,3-5,7,8 It found some small differences in outcomes among children exposed to marijuana prenatally. Of note, when investigators evaluated marijuana use at age 14 years, they compared adolescent self-report history with urine THC testing (specificity 78%).

The MHPCD study was limited because, compared with the nonusing group, mothers who used marijuana were also 20% to 25% more likely to be single and poor, to live in poorer quality homes, and to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Investigators used statistical modeling to account for these environmental differences and estimated that 10% of the difference in outcomes was attributable to prenatal marijuana exposure.

The Generation R study (Gen R) enrolled 220 lower-risk pregnancies in multiethnic European women of higher socioeconomic status, followed children to 3 years of age, and found no marijuana-associated differences in any parameter.1,3,4 The final assessment included only 51 children.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (including marijuana) during early pregnancy.9 Women who report marijuana use should be counseled regarding potential adverse consequences to fetal health and be encouraged to discontinue use.

ACOG says that insufficient data exist to evaluate the effects of marijuana use on infants during lactation and breastfeeding and recommends against it.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine also recommends screening pregnant women for drug use and making appropriate referrals for substance use treatment.10

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

1. Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:761-778.

2. Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:506.e1-e7.

3. Warner TD, Roussos-Ross D, Behnke M. It’s not your mother’s marijuana: effects on maternal-fetal health and the developing child. Clinical Perinatology. 2014;41:877-894.

4. Huizink AC. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45-52.

5. Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

6. Fried PA. The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS): methodological issues and findings—it’s easy to throw the baby out with the bath water. Life Sci. 1995;56:2159-2168.

7. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

8. Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313-1322.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:234-238.

10. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on women, alcohol and other drugs, and pregnancy. Chevy Chase MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1womenandpregnancy_7-11.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The effects are unclear. Marijuana use during pregnancy is associated with clinically unimportant lower birth weights (growth differences of approximately 100 g), but no differences in preterm births or congenital anomalies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies with methodologic flaws).

Similarly, prenatal marijuana use isn’t associated with differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes (behavior problems, intellect, visual perception, language, or sustained attention and memory tasks) at birth, in the neonatal period, or in childhood through age 3 years. However, it may be associated with minimally lower verbal/quantitative IQ scores (1%) at age 6 years and increased impulsivity and hyperactivity (1%) at 10 years. Prenatal use isn’t linked to increased substance use at age 14 years (SOR: B, conflicting long-term prospective and retrospective cohort studies with methodologic flaws).