User login

Immunizing the Adult Patient

Reported incidence rates of certain vaccine-preventable diseases—measles, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and tetanus—are low in the United States.1 However, as was demonstrated during the 2009-2010 flu season and the outbreak of H1N1 influenza,2 we cannot afford to be complacent in our attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination. New virus strains exist and can become endemic quickly and ravenously. Furthermore, certain vaccine-preventable illnesses are frequently reported among adult patients, including hepatitis B, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus infection, influenza, pertussis, and pneumococcal infection.3

Vigilance regarding vaccination of children and adults was addressed by the CDC’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion in Healthy People 2010.4 These target objectives are proposed to be retained in Healthy People 2020,5 as the objectives from 2010 have not been met. The Healthy People 2010 target for administration of the pneumococcal vaccine in adults ages 65 and older, for example, is 90%. As of 2008, research has shown, only 60% of that population was immunized.6

There are subgroups of immunocompromised people who will probably never achieve adequate antibody levels to ensure immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases (for example, measles and influenza can be deadly to the immunocompromised person, as they can be to the very young and the very old). This is an important reason why vaccination of the healthy population is essential: the concept of herd immunity.7 Herd immunity (or community immunity) suggests that if most people around you are immune to an infection and do not become ill, then there is no one who can infect you—even if you are not immune to the infection.

WHY SOME ADULTS MIGHT NEED VACCINES

Adults who were vaccinated as children may incorrectly assume that they are protected from disease for life. In the case of some diseases, this may be true. However:

• Some adults were never vaccinated as children

• Newer vaccines have been developed since many adults were children

• Immunity can begin to fade over time

• As we age, we become more susceptible to serious disease caused by common infections (eg, influenza, pneumococcus).8

Barriers to Vaccination

Barriers to vaccination are varied, but none is insurmountable. Some of these barriers include8-15:

Missed opportunities. Providers should address vaccination needs for both adults and children at each visit or encounter. According to the CDC, studies have shown that eliminating missed opportunities could increase vaccination coverage by as much as 20%.8,11

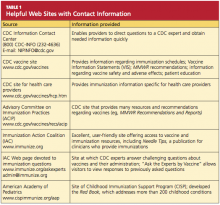

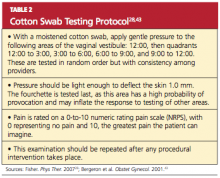

Provider misconceptions regarding vaccine contraindications, schedules, and simultaneous vaccine administration. These misconceptions may prompt providers to forego an opportunity to vaccinate. Up-to-date information about vaccinations and ongoing provider education are imperative to improve immunity among both adults and children against vaccine-preventable disease.8 Numerous Web sites and publications are instrumental and essential in furnishing the health care provider with the most current information about vaccinations (see Table 1, above, and Table 2,10,12-14).

A belief on patients’ part that they are fully vaccinated when they are not. It is important to provide a vaccination record and a return date at every vaccination encounter, even if just one vaccination has been administered on a given day. Participating in Immunization Information System,15 if one is available, is an efficient way to access computerized vaccine records easily at the point of contact.

Just as parents should be encouraged to bring their child’s vaccine record with them to every health care visit, adults are also called upon to maintain a record of all their vaccinations. Each entry in the immunization record should include:

• The type of vaccine and dose

• The site and route of administration

• The date that the vaccine was administered

• The date that the next dose is due

• The manufacturer and lot number

• The name, address, and title of the person who administered the vaccine.15

PRINCIPLES OF VACCINATION

There are two ways to acquire immunity: active and passive.

Active immunity is produced by the individual’s own immune system and usually represents a permanent immunity toward the antigen.10,16

Passive immunity is produced when the individual receives products of immunity made by another animal or a human and transferred to the host. Passive immunity can be accomplished by injection of these products or through the placenta in infants. This type of immunity is not permanent and wanes over time—usually within weeks or months.10,16

This article will concentrate on active immunity, acquired through the administration of vaccines.

CLASSIFICATION OF VACCINES

Vaccines are classified as either live, attenuated vaccine (viral or bacterial) or inactivated vaccine.

Live, attenuated vaccines are derived from “wild” or disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Through procedures conducted in the laboratory, these wild organisms are weakened or attenuated. The live, attenuated vaccine must grow and replicate in the vaccinated person in order to stimulate an immune response. However, because the organism has been weakened, it usually does not cause disease or illness.10,16

The immune response to a live, attenuated vaccine is virtually identical to a response produced by natural infection. In rare instances, however, live, attenuated vaccines may cause severe or fatal reactions as a result of uncontrolled replication of the organism. This occurs only in individuals who are significantly immunocompromised.10,16

Inactivated vaccines are produced by growing the viral or bacterial organism in a culture medium, then using heat and/or chemicals to inactivate the organism. Because inactivated vaccines are not alive, they cannot replicate, and therefore cannot cause disease, even in an immunodeficient patient. The immune response to an inactivated vaccine is mostly humoral (in contrast to the natural infection response of a live vaccine), and little or no cellular immunity is produced.10,16

Inactivated vaccines always require multiple doses, gradually building up a protective immune response. The antibody titers diminish over time, so some inactivated vaccines may require periodic doses to “boost” or increase the titers.16

Some vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine, lead to the development of immune memory, which stays intact for at least 20 years following immunization. Immune memory occurs during replication of B cells and T cells; some cells will become long-lived memory cells that will “remember” the pathogen and produce an immune response if the pathogen is detected again. In this case, boosters are not recommended.10

Toxoids are a type of vaccine made from the inactivated toxin of a bacterium—not the bacterium itself. Tetanus and diphtheria vaccines are examples of toxoid vaccines.10,16

Subunit and conjugate vaccines are segments of the pathogen. A subunit vaccine can be created via genetic engineering. The end result is a recombinant vaccine that can stimulate cell memory (eg, hepatitis B vaccine).10,16 Conjugate vaccines, which are similar to recombinant vaccines, are made by combining two different components to prompt a more powerful, combined immune response.10

Spacing of Live-Virus and Inactivated Vaccines

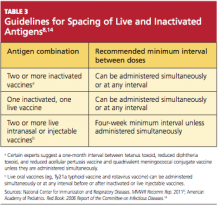

There are almost no spacing requirements between two or more inactivated vaccines8 (see Table 38,14 for spacing recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP]). The only vaccines that must be spaced at least four weeks apart are live-virus vaccines—that is, if they are not given on the same day. Studies have shown that the immune response to a live-virus vaccine may be impaired if it is administered within 30 days of another live-virus vaccine. Inactivated vaccines, on the other hand, may usually be administered at any time after or before a live-virus vaccine.8

One exception to this statement is the administration of Zostavax (zoster live-virus vaccine) with Pneumovax 23 (inactivated pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent, MSD).17-19 The manufacturer of the two vaccines recommends a spacing of at least four weeks between them, based on research showing that concomitant use may result in reduced immunogenicity for Zostavax.20 However, as of this writing, ACIP has not revised its statement that both vaccines can be given at the same time or at any time before or after each other.21

Live-virus vaccines currently licensed in the US provide protection against diseases including measles/mumps/rubella, varicella, zoster (ie, shingles), influenza, and yellow fever.

ADULT VACCINATION HIGHLIGHTS

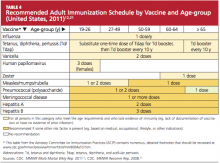

A summary of 2011 recommendations for adult immunization from ACIP is shown in Table 412,21. The following information is specific to each of the vaccine-preventable illnesses of concern in adults.12,13,22

Seasonal Influenza

The options to protect the adult patient against seasonal influenza are a trivalent, inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV; Fluzone, high-dose Fluzone for adults ages 65 and older, Fluvirin, Fluarix, FluLaval, Afluria, Agriflu) or a live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV; FluMist).2,23 Dosage of TIV for adults is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid once annually. For adults ages 49 and younger, LAIV is administered at 0.2 mL intranasally, once per year.

ACIP now recommends universal influenza vaccination for all persons ages 6 months and older with no contraindications.2,8 Strong consideration should be given to concurrent administration of influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine to high-risk persons not previously vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.12

Note: When influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are given at the same time, they should be administered in opposite arms to reduce the risk of adverse reactions or a decreased antibody response to either vaccine.18,19

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV)

Pneumovax 2319 is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid or subcutaneously in the upper arm. The vaccine is recommended for8,19,24:

• Adults ages 65 and older who have not been previously vaccinated

• Adults now 65 and older who received PPSV vaccine at least five years ago and were younger than 65 at that time

• Adults ages 19 through 64 years who have asthma or who smoke24

• Any adult with the following underlying medical conditions: chronic heart or lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, cochlear implants, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic alcoholism, functional or anatomic asplenia, and immunocompromising conditions (HIV infection, diseases that require immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy; congenital immunodeficiency).24

A one-time revaccination is recommended after five years for persons ages 19 to 64 who have chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, or functional or anatomic asplenia, and for those who are immunocompromised.24

Note: According to the manufacturer of Zostavax18 and Pneumovax,23,19 these vaccines should not be given at the same time, as research has shown that Zostavax immunogenicity is reduced as a result.18-20

Zoster

For adults ages 60 and older, Zostavax18 is administered in a single 0.65-mL dose, subcutaneously in the upper arm. Providers are not required to ask about varicella vaccination history or history of varicella disease before administering the vaccine. Adults ages 60 and older who have previously had shingles can still be vaccinated during a routine health care visit.10,21,22

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (most commonly, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Any adult patient who has close household or occupational contact with persons at risk for severe varicella (eg, infants) need not take precautions after receiving the zoster vaccine, except in the rare case in which a varicella-like rash develops.10,21,22

Note: Review the note appearing in “Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV),” above, regarding coadministration of Zostavax and Pneumovax 23.18-20

Varicella

Adults who were born in the US before 1980 are considered immune to varicella and don’t need to be vaccinated, with the exception of health care workers, pregnant women, and immunocompromised persons. Nonimmune healthy adults who have not previously undergone vaccination should receive two 0.5-mL doses of Varivax, administered subcutaneously, four to eight weeks apart.25

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (eg, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR)

The MMR vaccine is administered at 0.5 mL, given subcutaneously in the posterolateral fat of the upper arm.8

MMR-susceptible adults who were born during or since 1957 and are not at increased risk (see below) need only one dose of the MMR vaccine; those considered at increased risk need two doses, and a second dose can also be considered during an outbreak. Adults who require two doses should wait at least four weeks between the first and second doses.12

The following factors place adults at increased risk for MMR:

• Anticipated international travel

• Being a student in a post–secondary educational setting

• Working in a health care facility

• Recent exposure to measles, or an outbreak of measles or mumps

• Previous vaccination with killed measles vaccine

• Previous vaccination with an unknown measles vaccine between 1963 and 1967.

Also at risk are health care workers born before 1957 who have no evidence of immunity, and women who plan to become pregnant and have no evidence of immunity.8,12

Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis

Options for adults include a vaccine against tetanus and diphtheria (Td; Decavac); or a vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap; Adacel, Boostrix). Adults who have not been previously vaccinated should receive one dose of Tdap and two doses of Td (the first, one month after Tdap; the second at six to 12 months after the Tdap). Each is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid. A booster dose is recommended every 10 years but can be given earlier in patients who sustain wounds or who anticipate international travel.8,12

Adults ages 19 through 64 should receive a single dose of Tdap in place of a booster dose if the last Td dose was administered at least 10 years earlier and the patient has not previously received Tdap. Additionally, a dose of Tdap (if not previously given) is recommended for postpartum women, close contacts of infants younger than 12 months, and all health care workers with direct patient contact. An interval as short as two years from the last Td is suggested; shorter intervals may be appropriate.8,12

According to the new 2011 recommendations, persons ages 65 and older who have close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should be vaccinated with Tdap, and any person age 65 or older may be vaccinated with Tdap. Also added is a recommendation to administer Tdap, regardless of the interval since the patient received his or her most recent Td-containing vaccine.8,12

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Gardasil26 protects both female and male patients against HPV infection; Cervarix27 is indicated only for female patients. Either quadrivalent vaccine or bivalent vaccine is recommended for female patients.12

In women ages 26 and younger, Gardasil (0.5 mL IM, administered in the deltoid at 0 month, 2 months, and 6 months) provides protection against diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (including cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancer caused by HPV types 16 and 18). In men ages 26 and younger, Gardasil provides protection against genital warts caused by HPV types 6 and 11.26

Cervarix,27 administered at 0 month, 1 month, and 6 months (0.5 mL IM in the deltoid), provides protection for women ages 25 and younger against cervical cancer and precancerous lesions caused by HPV types 16 and 18.

Caution: Patients should be advised to sit or lie down when the HPV vaccine is administered, and they should be observed for the subsequent 15 minutes. Syncope can occur after vaccination—most commonly among adolescents and young adults.28 Convulsive syncope has been reported.

Meningococcal Disease

Two vaccines are available to protect against meningococcal disease: Menactra29 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 polysaccharide diphtheria toxoids conjugate vaccine); and Menveo30 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 oligosaccharide diphtheria CRM197 conjugate vaccine). Both are administered in the deltoid, 0.5 mL IM.

The following patients should be considered for vaccination:

• College freshmen living in dormitories, as well as college students with immune deficiencies, as they are at higher risk for meningococcal disease

• Patients who travel to or reside in countries in which Neisseria meningitidis is epidemic (particularly those with the potential for prolonged contact with the local population)

• Travelers to Saudi Arabia for pilgrimage to Mecca (the Hajj)

• Patients with anatomical or functional asplenia (two-dose series).

A two-dose series of meningococcal conjugate vaccine is also recommended for adults with persistent complement component deficiencies, and for those with HIV infection who are vaccinated.12

Hepatitis A

Two hepatitis A vaccines (both inactivated) can be used interchangeably: Havrix31 and Vaqta.32 Dosing for both vaccines in 18-year-old patients is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0 months, then at 6 to 12 months. In patients ages 19 and older, administration is the same, with the exception of increased dosing (1.0 mL IM).

Vaccination against hepatitis A is recommended for men who have sex with men, and for all adult patients who12:

• Travel to or work in areas where risk for hepatitis A transmission is high (especially those who take frequent trips or experience prolonged stays)

• Use injection drugs

• Have chronic liver disease

• Receive clotting factor concentrates for treatment of a blood-clotting disorder

• May have been exposed to hepatitis A in the previous two weeks

• Wish to be vaccinated against hepatitis A to avoid future infection.

Hepatitis B

Recombivax HB33 and Engerix-B34 are the two vaccines available to protect patients against hepatitis B (HBV), and they can be used interchangeably.12 In patients from birth through age 19, Recombivax HB33 or Engerix-B34 is given as 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0, 1, and 6 months; patients ages 20 and older receive an increased dose (1.0 mL IM), with administration otherwise the same. According to the manufacturer of Recombivax HB,33 patients age 11 through 15 may be given either three doses of 0.5 mL or two doses of 1.0 mL.

The following adults are advised to undergo vaccination for HBV:

• At-risk, unvaccinated adults

• Those requesting protection against HBV infection

• Those planning to travel to areas where HBV is common

• Household contacts of a patient with chronic HBV infection, and sexual partners of a patient with HBV infection

• Adults with chronic liver disease

• Men who have sex with men

• Sexually active adults who are not in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship

• Adults who are being evaluated or treated for a sexually transmitted disease, including HIV infection

• Health care or public safety workers who may be exposed to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids

• Workers and residents in facilities for developmentally disabled persons

• Patients undergoing or anticipating dialysis

• Adults who inject illegal drugs or who have done so recently.12

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS FOR VACCINES COMMONLY USED IN ADULTS

See Table 5,8,22 for a summary of contraindications and precautions from ACIP and the Immunization Action Coalition that are associated with vaccinations mentioned in this article. A more complete summary can be found at www.im munize.org/catg.d/p3072a.pdf.

Conclusion

The adult patient’s vaccination status should be addressed at each health care encounter, and current recommendations should be followed. The duration of efficacy for vaccines is not an exact science. Many vaccines licensed in the US are relatively new, and recommendations for boosters for some of these vaccines will be forthcoming as more data are gathered. For example, the recommendation that a booster dose of Tdap be given to adults resulted from the recent increase in reported pertussis cases.35

Providers armed with the most current information and resources represent the forefront in ensuring that the US adult population is adequately immunized.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Immunization surveillance, assessment, and monitoring (2010). www.who.int/immunization_monitor ing/en. Accessed May 12, 2011.

2. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-08);1-62.

3. Schaffner W. Update on vaccine-preventable diseases: are adults in your community adequately protected? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4 suppl):S1-S11.

4. CDC. Healthy People 2010: Objectives for Improving Health. www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed May 6, 2011.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Developing Healthy People 2020: immunization and infectious diseases. www.healthy people.gov/2020. Accessed May 12, 2011.

6. Lu PJ, Nuorti JP. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among adults aged 65 years and older, United States, 1989-2008. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):287-295.

7. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Community immunity (“herd” immunity) (2010). www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/pages/communityimmunity.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2011.

8. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ADIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

9. High KP. Overcoming barriers to adult immunization. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(6): 525-528.

10. CDC; Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, eds. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (Pink Book). 12th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, 2011.

11. CDC. Vaccine-preventable diseases: improving vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults: a report on recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-8):1-15.

12. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

13. Thompson RF. Travel & Routine Immunizations: A Practical Guide for the Medical Office. 19th ed. Milwaukee, WI: Shoreland, Inc: 2001.

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pertussis. In: Pickering LK, Backer, CJ, Long SS, McMillan J, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

15. CDC. Immunization information systems (IIS). www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/default.htm. Accessed May 12, 2011.

16. College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The history of vaccines: a project of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (2011). www.history ofvaccines.org/content/articles/different-types-vaccines. Accessed May 12, 2011.

17. US Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines, blood, and biologics: December 18, 2009 Approval Letter—Zostavax. www.fda.gov/

BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved Products/ucm195993.htm. Accessed May 12, 2011.

18. Merck & Co, Inc. Zostavax® (zoster vaccine live; product insert). www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved Products/UCM132831.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

19. Merck & Co, Inc. Pneumovax® 23 (pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent, MSD; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/p/pneumovax_23/pneumovax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2011.

20. Macintyre CR, Egerton T, McCaughey M, et al. Concomitant administration of zoster and pneumococcal vaccines in adults ≥60 years old. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6(11):18-26.

21. CDC. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-5):1–30.

22. Immunization Action Coalition. Vaccinate Adults. 2010 Aug;14(5). www.immunize.org/va. Accessed May 12, 2011.

23. CDC. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding use of CSL seasonal influenza vaccine (Afluria) in the United States during 2010–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(31);989-992.

24. CDC. Updated recommendations for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults using the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-34):1102-1106.

25. Merck & Co, Inc. Varivax® varicella virus vaccine live (product information). www.merck

.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/v/varivax/varivax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

26. Merck & Co, Inc. Gardasil® (human papillomavirus quadrivalent [types 6, 11, 16, and 18] vaccine, recombinant; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/g/gardasil/gardasil_ppi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

27. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Cervarix (human papillomavirus bivalent [types 16 and 18] vaccine, recombinant; product information). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_cervarix.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

28. CDC. Syncope after vaccination—United States, January 2005-July 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(17):457-460.

29. Sanofi Pasteur. Meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, and W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria

toxoids conjugate vaccine Menactra® for intramuscular injection. www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved

Products/UCM131170.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

30. Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Inc. Menveo® (meningococcal [groups A, C, Y and W-135] oligosaccharide diphtheria CRM197 conjugate vaccine solution for intramuscular injection; prescribing information highlights). www .fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm201349.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

31. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Havrix (hepatitis A vaccine, suspension for intramuscular injection; prescribing information highlights). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_havrix .pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

32. Merck & Co, Inc. Vaqta (hepatitis A vaccine, inactivated; suspension for intramuscular injection; highlighted prescribing information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/v/vaqta/vaqta_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

33. Merck & Co, Inc. Recombivax HB® hepatitis B vaccine (recombinant; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/r/recombivax_hb/recombivax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

34. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Engerix-B® (hepatitis B vaccine, recombinant; prescribing information). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_engerixb.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

35. CDC. Tetanus and pertussis vaccination coverage among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 1999 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(40):1302-1306.

Reported incidence rates of certain vaccine-preventable diseases—measles, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and tetanus—are low in the United States.1 However, as was demonstrated during the 2009-2010 flu season and the outbreak of H1N1 influenza,2 we cannot afford to be complacent in our attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination. New virus strains exist and can become endemic quickly and ravenously. Furthermore, certain vaccine-preventable illnesses are frequently reported among adult patients, including hepatitis B, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus infection, influenza, pertussis, and pneumococcal infection.3

Vigilance regarding vaccination of children and adults was addressed by the CDC’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion in Healthy People 2010.4 These target objectives are proposed to be retained in Healthy People 2020,5 as the objectives from 2010 have not been met. The Healthy People 2010 target for administration of the pneumococcal vaccine in adults ages 65 and older, for example, is 90%. As of 2008, research has shown, only 60% of that population was immunized.6

There are subgroups of immunocompromised people who will probably never achieve adequate antibody levels to ensure immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases (for example, measles and influenza can be deadly to the immunocompromised person, as they can be to the very young and the very old). This is an important reason why vaccination of the healthy population is essential: the concept of herd immunity.7 Herd immunity (or community immunity) suggests that if most people around you are immune to an infection and do not become ill, then there is no one who can infect you—even if you are not immune to the infection.

WHY SOME ADULTS MIGHT NEED VACCINES

Adults who were vaccinated as children may incorrectly assume that they are protected from disease for life. In the case of some diseases, this may be true. However:

• Some adults were never vaccinated as children

• Newer vaccines have been developed since many adults were children

• Immunity can begin to fade over time

• As we age, we become more susceptible to serious disease caused by common infections (eg, influenza, pneumococcus).8

Barriers to Vaccination

Barriers to vaccination are varied, but none is insurmountable. Some of these barriers include8-15:

Missed opportunities. Providers should address vaccination needs for both adults and children at each visit or encounter. According to the CDC, studies have shown that eliminating missed opportunities could increase vaccination coverage by as much as 20%.8,11

Provider misconceptions regarding vaccine contraindications, schedules, and simultaneous vaccine administration. These misconceptions may prompt providers to forego an opportunity to vaccinate. Up-to-date information about vaccinations and ongoing provider education are imperative to improve immunity among both adults and children against vaccine-preventable disease.8 Numerous Web sites and publications are instrumental and essential in furnishing the health care provider with the most current information about vaccinations (see Table 1, above, and Table 2,10,12-14).

A belief on patients’ part that they are fully vaccinated when they are not. It is important to provide a vaccination record and a return date at every vaccination encounter, even if just one vaccination has been administered on a given day. Participating in Immunization Information System,15 if one is available, is an efficient way to access computerized vaccine records easily at the point of contact.

Just as parents should be encouraged to bring their child’s vaccine record with them to every health care visit, adults are also called upon to maintain a record of all their vaccinations. Each entry in the immunization record should include:

• The type of vaccine and dose

• The site and route of administration

• The date that the vaccine was administered

• The date that the next dose is due

• The manufacturer and lot number

• The name, address, and title of the person who administered the vaccine.15

PRINCIPLES OF VACCINATION

There are two ways to acquire immunity: active and passive.

Active immunity is produced by the individual’s own immune system and usually represents a permanent immunity toward the antigen.10,16

Passive immunity is produced when the individual receives products of immunity made by another animal or a human and transferred to the host. Passive immunity can be accomplished by injection of these products or through the placenta in infants. This type of immunity is not permanent and wanes over time—usually within weeks or months.10,16

This article will concentrate on active immunity, acquired through the administration of vaccines.

CLASSIFICATION OF VACCINES

Vaccines are classified as either live, attenuated vaccine (viral or bacterial) or inactivated vaccine.

Live, attenuated vaccines are derived from “wild” or disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Through procedures conducted in the laboratory, these wild organisms are weakened or attenuated. The live, attenuated vaccine must grow and replicate in the vaccinated person in order to stimulate an immune response. However, because the organism has been weakened, it usually does not cause disease or illness.10,16

The immune response to a live, attenuated vaccine is virtually identical to a response produced by natural infection. In rare instances, however, live, attenuated vaccines may cause severe or fatal reactions as a result of uncontrolled replication of the organism. This occurs only in individuals who are significantly immunocompromised.10,16

Inactivated vaccines are produced by growing the viral or bacterial organism in a culture medium, then using heat and/or chemicals to inactivate the organism. Because inactivated vaccines are not alive, they cannot replicate, and therefore cannot cause disease, even in an immunodeficient patient. The immune response to an inactivated vaccine is mostly humoral (in contrast to the natural infection response of a live vaccine), and little or no cellular immunity is produced.10,16

Inactivated vaccines always require multiple doses, gradually building up a protective immune response. The antibody titers diminish over time, so some inactivated vaccines may require periodic doses to “boost” or increase the titers.16

Some vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine, lead to the development of immune memory, which stays intact for at least 20 years following immunization. Immune memory occurs during replication of B cells and T cells; some cells will become long-lived memory cells that will “remember” the pathogen and produce an immune response if the pathogen is detected again. In this case, boosters are not recommended.10

Toxoids are a type of vaccine made from the inactivated toxin of a bacterium—not the bacterium itself. Tetanus and diphtheria vaccines are examples of toxoid vaccines.10,16

Subunit and conjugate vaccines are segments of the pathogen. A subunit vaccine can be created via genetic engineering. The end result is a recombinant vaccine that can stimulate cell memory (eg, hepatitis B vaccine).10,16 Conjugate vaccines, which are similar to recombinant vaccines, are made by combining two different components to prompt a more powerful, combined immune response.10

Spacing of Live-Virus and Inactivated Vaccines

There are almost no spacing requirements between two or more inactivated vaccines8 (see Table 38,14 for spacing recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP]). The only vaccines that must be spaced at least four weeks apart are live-virus vaccines—that is, if they are not given on the same day. Studies have shown that the immune response to a live-virus vaccine may be impaired if it is administered within 30 days of another live-virus vaccine. Inactivated vaccines, on the other hand, may usually be administered at any time after or before a live-virus vaccine.8

One exception to this statement is the administration of Zostavax (zoster live-virus vaccine) with Pneumovax 23 (inactivated pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent, MSD).17-19 The manufacturer of the two vaccines recommends a spacing of at least four weeks between them, based on research showing that concomitant use may result in reduced immunogenicity for Zostavax.20 However, as of this writing, ACIP has not revised its statement that both vaccines can be given at the same time or at any time before or after each other.21

Live-virus vaccines currently licensed in the US provide protection against diseases including measles/mumps/rubella, varicella, zoster (ie, shingles), influenza, and yellow fever.

ADULT VACCINATION HIGHLIGHTS

A summary of 2011 recommendations for adult immunization from ACIP is shown in Table 412,21. The following information is specific to each of the vaccine-preventable illnesses of concern in adults.12,13,22

Seasonal Influenza

The options to protect the adult patient against seasonal influenza are a trivalent, inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV; Fluzone, high-dose Fluzone for adults ages 65 and older, Fluvirin, Fluarix, FluLaval, Afluria, Agriflu) or a live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV; FluMist).2,23 Dosage of TIV for adults is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid once annually. For adults ages 49 and younger, LAIV is administered at 0.2 mL intranasally, once per year.

ACIP now recommends universal influenza vaccination for all persons ages 6 months and older with no contraindications.2,8 Strong consideration should be given to concurrent administration of influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine to high-risk persons not previously vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.12

Note: When influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are given at the same time, they should be administered in opposite arms to reduce the risk of adverse reactions or a decreased antibody response to either vaccine.18,19

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV)

Pneumovax 2319 is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid or subcutaneously in the upper arm. The vaccine is recommended for8,19,24:

• Adults ages 65 and older who have not been previously vaccinated

• Adults now 65 and older who received PPSV vaccine at least five years ago and were younger than 65 at that time

• Adults ages 19 through 64 years who have asthma or who smoke24

• Any adult with the following underlying medical conditions: chronic heart or lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, cochlear implants, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic alcoholism, functional or anatomic asplenia, and immunocompromising conditions (HIV infection, diseases that require immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy; congenital immunodeficiency).24

A one-time revaccination is recommended after five years for persons ages 19 to 64 who have chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, or functional or anatomic asplenia, and for those who are immunocompromised.24

Note: According to the manufacturer of Zostavax18 and Pneumovax,23,19 these vaccines should not be given at the same time, as research has shown that Zostavax immunogenicity is reduced as a result.18-20

Zoster

For adults ages 60 and older, Zostavax18 is administered in a single 0.65-mL dose, subcutaneously in the upper arm. Providers are not required to ask about varicella vaccination history or history of varicella disease before administering the vaccine. Adults ages 60 and older who have previously had shingles can still be vaccinated during a routine health care visit.10,21,22

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (most commonly, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Any adult patient who has close household or occupational contact with persons at risk for severe varicella (eg, infants) need not take precautions after receiving the zoster vaccine, except in the rare case in which a varicella-like rash develops.10,21,22

Note: Review the note appearing in “Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV),” above, regarding coadministration of Zostavax and Pneumovax 23.18-20

Varicella

Adults who were born in the US before 1980 are considered immune to varicella and don’t need to be vaccinated, with the exception of health care workers, pregnant women, and immunocompromised persons. Nonimmune healthy adults who have not previously undergone vaccination should receive two 0.5-mL doses of Varivax, administered subcutaneously, four to eight weeks apart.25

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (eg, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR)

The MMR vaccine is administered at 0.5 mL, given subcutaneously in the posterolateral fat of the upper arm.8

MMR-susceptible adults who were born during or since 1957 and are not at increased risk (see below) need only one dose of the MMR vaccine; those considered at increased risk need two doses, and a second dose can also be considered during an outbreak. Adults who require two doses should wait at least four weeks between the first and second doses.12

The following factors place adults at increased risk for MMR:

• Anticipated international travel

• Being a student in a post–secondary educational setting

• Working in a health care facility

• Recent exposure to measles, or an outbreak of measles or mumps

• Previous vaccination with killed measles vaccine

• Previous vaccination with an unknown measles vaccine between 1963 and 1967.

Also at risk are health care workers born before 1957 who have no evidence of immunity, and women who plan to become pregnant and have no evidence of immunity.8,12

Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis

Options for adults include a vaccine against tetanus and diphtheria (Td; Decavac); or a vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap; Adacel, Boostrix). Adults who have not been previously vaccinated should receive one dose of Tdap and two doses of Td (the first, one month after Tdap; the second at six to 12 months after the Tdap). Each is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid. A booster dose is recommended every 10 years but can be given earlier in patients who sustain wounds or who anticipate international travel.8,12

Adults ages 19 through 64 should receive a single dose of Tdap in place of a booster dose if the last Td dose was administered at least 10 years earlier and the patient has not previously received Tdap. Additionally, a dose of Tdap (if not previously given) is recommended for postpartum women, close contacts of infants younger than 12 months, and all health care workers with direct patient contact. An interval as short as two years from the last Td is suggested; shorter intervals may be appropriate.8,12

According to the new 2011 recommendations, persons ages 65 and older who have close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should be vaccinated with Tdap, and any person age 65 or older may be vaccinated with Tdap. Also added is a recommendation to administer Tdap, regardless of the interval since the patient received his or her most recent Td-containing vaccine.8,12

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Gardasil26 protects both female and male patients against HPV infection; Cervarix27 is indicated only for female patients. Either quadrivalent vaccine or bivalent vaccine is recommended for female patients.12

In women ages 26 and younger, Gardasil (0.5 mL IM, administered in the deltoid at 0 month, 2 months, and 6 months) provides protection against diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (including cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancer caused by HPV types 16 and 18). In men ages 26 and younger, Gardasil provides protection against genital warts caused by HPV types 6 and 11.26

Cervarix,27 administered at 0 month, 1 month, and 6 months (0.5 mL IM in the deltoid), provides protection for women ages 25 and younger against cervical cancer and precancerous lesions caused by HPV types 16 and 18.

Caution: Patients should be advised to sit or lie down when the HPV vaccine is administered, and they should be observed for the subsequent 15 minutes. Syncope can occur after vaccination—most commonly among adolescents and young adults.28 Convulsive syncope has been reported.

Meningococcal Disease

Two vaccines are available to protect against meningococcal disease: Menactra29 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 polysaccharide diphtheria toxoids conjugate vaccine); and Menveo30 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 oligosaccharide diphtheria CRM197 conjugate vaccine). Both are administered in the deltoid, 0.5 mL IM.

The following patients should be considered for vaccination:

• College freshmen living in dormitories, as well as college students with immune deficiencies, as they are at higher risk for meningococcal disease

• Patients who travel to or reside in countries in which Neisseria meningitidis is epidemic (particularly those with the potential for prolonged contact with the local population)

• Travelers to Saudi Arabia for pilgrimage to Mecca (the Hajj)

• Patients with anatomical or functional asplenia (two-dose series).

A two-dose series of meningococcal conjugate vaccine is also recommended for adults with persistent complement component deficiencies, and for those with HIV infection who are vaccinated.12

Hepatitis A

Two hepatitis A vaccines (both inactivated) can be used interchangeably: Havrix31 and Vaqta.32 Dosing for both vaccines in 18-year-old patients is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0 months, then at 6 to 12 months. In patients ages 19 and older, administration is the same, with the exception of increased dosing (1.0 mL IM).

Vaccination against hepatitis A is recommended for men who have sex with men, and for all adult patients who12:

• Travel to or work in areas where risk for hepatitis A transmission is high (especially those who take frequent trips or experience prolonged stays)

• Use injection drugs

• Have chronic liver disease

• Receive clotting factor concentrates for treatment of a blood-clotting disorder

• May have been exposed to hepatitis A in the previous two weeks

• Wish to be vaccinated against hepatitis A to avoid future infection.

Hepatitis B

Recombivax HB33 and Engerix-B34 are the two vaccines available to protect patients against hepatitis B (HBV), and they can be used interchangeably.12 In patients from birth through age 19, Recombivax HB33 or Engerix-B34 is given as 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0, 1, and 6 months; patients ages 20 and older receive an increased dose (1.0 mL IM), with administration otherwise the same. According to the manufacturer of Recombivax HB,33 patients age 11 through 15 may be given either three doses of 0.5 mL or two doses of 1.0 mL.

The following adults are advised to undergo vaccination for HBV:

• At-risk, unvaccinated adults

• Those requesting protection against HBV infection

• Those planning to travel to areas where HBV is common

• Household contacts of a patient with chronic HBV infection, and sexual partners of a patient with HBV infection

• Adults with chronic liver disease

• Men who have sex with men

• Sexually active adults who are not in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship

• Adults who are being evaluated or treated for a sexually transmitted disease, including HIV infection

• Health care or public safety workers who may be exposed to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids

• Workers and residents in facilities for developmentally disabled persons

• Patients undergoing or anticipating dialysis

• Adults who inject illegal drugs or who have done so recently.12

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS FOR VACCINES COMMONLY USED IN ADULTS

See Table 5,8,22 for a summary of contraindications and precautions from ACIP and the Immunization Action Coalition that are associated with vaccinations mentioned in this article. A more complete summary can be found at www.im munize.org/catg.d/p3072a.pdf.

Conclusion

The adult patient’s vaccination status should be addressed at each health care encounter, and current recommendations should be followed. The duration of efficacy for vaccines is not an exact science. Many vaccines licensed in the US are relatively new, and recommendations for boosters for some of these vaccines will be forthcoming as more data are gathered. For example, the recommendation that a booster dose of Tdap be given to adults resulted from the recent increase in reported pertussis cases.35

Providers armed with the most current information and resources represent the forefront in ensuring that the US adult population is adequately immunized.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Immunization surveillance, assessment, and monitoring (2010). www.who.int/immunization_monitor ing/en. Accessed May 12, 2011.

2. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-08);1-62.

3. Schaffner W. Update on vaccine-preventable diseases: are adults in your community adequately protected? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4 suppl):S1-S11.

4. CDC. Healthy People 2010: Objectives for Improving Health. www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed May 6, 2011.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Developing Healthy People 2020: immunization and infectious diseases. www.healthy people.gov/2020. Accessed May 12, 2011.

6. Lu PJ, Nuorti JP. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among adults aged 65 years and older, United States, 1989-2008. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):287-295.

7. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Community immunity (“herd” immunity) (2010). www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/pages/communityimmunity.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2011.

8. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ADIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

9. High KP. Overcoming barriers to adult immunization. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(6): 525-528.

10. CDC; Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, eds. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (Pink Book). 12th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, 2011.

11. CDC. Vaccine-preventable diseases: improving vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults: a report on recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-8):1-15.

12. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

13. Thompson RF. Travel & Routine Immunizations: A Practical Guide for the Medical Office. 19th ed. Milwaukee, WI: Shoreland, Inc: 2001.

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pertussis. In: Pickering LK, Backer, CJ, Long SS, McMillan J, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

15. CDC. Immunization information systems (IIS). www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/default.htm. Accessed May 12, 2011.

16. College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The history of vaccines: a project of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (2011). www.history ofvaccines.org/content/articles/different-types-vaccines. Accessed May 12, 2011.

17. US Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines, blood, and biologics: December 18, 2009 Approval Letter—Zostavax. www.fda.gov/

BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved Products/ucm195993.htm. Accessed May 12, 2011.

18. Merck & Co, Inc. Zostavax® (zoster vaccine live; product insert). www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved Products/UCM132831.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

19. Merck & Co, Inc. Pneumovax® 23 (pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent, MSD; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/p/pneumovax_23/pneumovax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2011.

20. Macintyre CR, Egerton T, McCaughey M, et al. Concomitant administration of zoster and pneumococcal vaccines in adults ≥60 years old. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6(11):18-26.

21. CDC. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-5):1–30.

22. Immunization Action Coalition. Vaccinate Adults. 2010 Aug;14(5). www.immunize.org/va. Accessed May 12, 2011.

23. CDC. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding use of CSL seasonal influenza vaccine (Afluria) in the United States during 2010–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(31);989-992.

24. CDC. Updated recommendations for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults using the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-34):1102-1106.

25. Merck & Co, Inc. Varivax® varicella virus vaccine live (product information). www.merck

.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/v/varivax/varivax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

26. Merck & Co, Inc. Gardasil® (human papillomavirus quadrivalent [types 6, 11, 16, and 18] vaccine, recombinant; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/g/gardasil/gardasil_ppi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

27. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Cervarix (human papillomavirus bivalent [types 16 and 18] vaccine, recombinant; product information). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_cervarix.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

28. CDC. Syncope after vaccination—United States, January 2005-July 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(17):457-460.

29. Sanofi Pasteur. Meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, and W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria

toxoids conjugate vaccine Menactra® for intramuscular injection. www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/Approved

Products/UCM131170.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

30. Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Inc. Menveo® (meningococcal [groups A, C, Y and W-135] oligosaccharide diphtheria CRM197 conjugate vaccine solution for intramuscular injection; prescribing information highlights). www .fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm201349.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

31. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Havrix (hepatitis A vaccine, suspension for intramuscular injection; prescribing information highlights). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_havrix .pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

32. Merck & Co, Inc. Vaqta (hepatitis A vaccine, inactivated; suspension for intramuscular injection; highlighted prescribing information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/v/vaqta/vaqta_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

33. Merck & Co, Inc. Recombivax HB® hepatitis B vaccine (recombinant; product information). www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/r/recombivax_hb/recombivax_pi.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

34. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Engerix-B® (hepatitis B vaccine, recombinant; prescribing information). http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_engerixb.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2011.

35. CDC. Tetanus and pertussis vaccination coverage among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 1999 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(40):1302-1306.

Reported incidence rates of certain vaccine-preventable diseases—measles, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and tetanus—are low in the United States.1 However, as was demonstrated during the 2009-2010 flu season and the outbreak of H1N1 influenza,2 we cannot afford to be complacent in our attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination. New virus strains exist and can become endemic quickly and ravenously. Furthermore, certain vaccine-preventable illnesses are frequently reported among adult patients, including hepatitis B, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus infection, influenza, pertussis, and pneumococcal infection.3

Vigilance regarding vaccination of children and adults was addressed by the CDC’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion in Healthy People 2010.4 These target objectives are proposed to be retained in Healthy People 2020,5 as the objectives from 2010 have not been met. The Healthy People 2010 target for administration of the pneumococcal vaccine in adults ages 65 and older, for example, is 90%. As of 2008, research has shown, only 60% of that population was immunized.6

There are subgroups of immunocompromised people who will probably never achieve adequate antibody levels to ensure immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases (for example, measles and influenza can be deadly to the immunocompromised person, as they can be to the very young and the very old). This is an important reason why vaccination of the healthy population is essential: the concept of herd immunity.7 Herd immunity (or community immunity) suggests that if most people around you are immune to an infection and do not become ill, then there is no one who can infect you—even if you are not immune to the infection.

WHY SOME ADULTS MIGHT NEED VACCINES

Adults who were vaccinated as children may incorrectly assume that they are protected from disease for life. In the case of some diseases, this may be true. However:

• Some adults were never vaccinated as children

• Newer vaccines have been developed since many adults were children

• Immunity can begin to fade over time

• As we age, we become more susceptible to serious disease caused by common infections (eg, influenza, pneumococcus).8

Barriers to Vaccination

Barriers to vaccination are varied, but none is insurmountable. Some of these barriers include8-15:

Missed opportunities. Providers should address vaccination needs for both adults and children at each visit or encounter. According to the CDC, studies have shown that eliminating missed opportunities could increase vaccination coverage by as much as 20%.8,11

Provider misconceptions regarding vaccine contraindications, schedules, and simultaneous vaccine administration. These misconceptions may prompt providers to forego an opportunity to vaccinate. Up-to-date information about vaccinations and ongoing provider education are imperative to improve immunity among both adults and children against vaccine-preventable disease.8 Numerous Web sites and publications are instrumental and essential in furnishing the health care provider with the most current information about vaccinations (see Table 1, above, and Table 2,10,12-14).

A belief on patients’ part that they are fully vaccinated when they are not. It is important to provide a vaccination record and a return date at every vaccination encounter, even if just one vaccination has been administered on a given day. Participating in Immunization Information System,15 if one is available, is an efficient way to access computerized vaccine records easily at the point of contact.

Just as parents should be encouraged to bring their child’s vaccine record with them to every health care visit, adults are also called upon to maintain a record of all their vaccinations. Each entry in the immunization record should include:

• The type of vaccine and dose

• The site and route of administration

• The date that the vaccine was administered

• The date that the next dose is due

• The manufacturer and lot number

• The name, address, and title of the person who administered the vaccine.15

PRINCIPLES OF VACCINATION

There are two ways to acquire immunity: active and passive.

Active immunity is produced by the individual’s own immune system and usually represents a permanent immunity toward the antigen.10,16

Passive immunity is produced when the individual receives products of immunity made by another animal or a human and transferred to the host. Passive immunity can be accomplished by injection of these products or through the placenta in infants. This type of immunity is not permanent and wanes over time—usually within weeks or months.10,16

This article will concentrate on active immunity, acquired through the administration of vaccines.

CLASSIFICATION OF VACCINES

Vaccines are classified as either live, attenuated vaccine (viral or bacterial) or inactivated vaccine.

Live, attenuated vaccines are derived from “wild” or disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Through procedures conducted in the laboratory, these wild organisms are weakened or attenuated. The live, attenuated vaccine must grow and replicate in the vaccinated person in order to stimulate an immune response. However, because the organism has been weakened, it usually does not cause disease or illness.10,16

The immune response to a live, attenuated vaccine is virtually identical to a response produced by natural infection. In rare instances, however, live, attenuated vaccines may cause severe or fatal reactions as a result of uncontrolled replication of the organism. This occurs only in individuals who are significantly immunocompromised.10,16

Inactivated vaccines are produced by growing the viral or bacterial organism in a culture medium, then using heat and/or chemicals to inactivate the organism. Because inactivated vaccines are not alive, they cannot replicate, and therefore cannot cause disease, even in an immunodeficient patient. The immune response to an inactivated vaccine is mostly humoral (in contrast to the natural infection response of a live vaccine), and little or no cellular immunity is produced.10,16

Inactivated vaccines always require multiple doses, gradually building up a protective immune response. The antibody titers diminish over time, so some inactivated vaccines may require periodic doses to “boost” or increase the titers.16

Some vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine, lead to the development of immune memory, which stays intact for at least 20 years following immunization. Immune memory occurs during replication of B cells and T cells; some cells will become long-lived memory cells that will “remember” the pathogen and produce an immune response if the pathogen is detected again. In this case, boosters are not recommended.10

Toxoids are a type of vaccine made from the inactivated toxin of a bacterium—not the bacterium itself. Tetanus and diphtheria vaccines are examples of toxoid vaccines.10,16

Subunit and conjugate vaccines are segments of the pathogen. A subunit vaccine can be created via genetic engineering. The end result is a recombinant vaccine that can stimulate cell memory (eg, hepatitis B vaccine).10,16 Conjugate vaccines, which are similar to recombinant vaccines, are made by combining two different components to prompt a more powerful, combined immune response.10

Spacing of Live-Virus and Inactivated Vaccines

There are almost no spacing requirements between two or more inactivated vaccines8 (see Table 38,14 for spacing recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP]). The only vaccines that must be spaced at least four weeks apart are live-virus vaccines—that is, if they are not given on the same day. Studies have shown that the immune response to a live-virus vaccine may be impaired if it is administered within 30 days of another live-virus vaccine. Inactivated vaccines, on the other hand, may usually be administered at any time after or before a live-virus vaccine.8

One exception to this statement is the administration of Zostavax (zoster live-virus vaccine) with Pneumovax 23 (inactivated pneumococcal vaccine, polyvalent, MSD).17-19 The manufacturer of the two vaccines recommends a spacing of at least four weeks between them, based on research showing that concomitant use may result in reduced immunogenicity for Zostavax.20 However, as of this writing, ACIP has not revised its statement that both vaccines can be given at the same time or at any time before or after each other.21

Live-virus vaccines currently licensed in the US provide protection against diseases including measles/mumps/rubella, varicella, zoster (ie, shingles), influenza, and yellow fever.

ADULT VACCINATION HIGHLIGHTS

A summary of 2011 recommendations for adult immunization from ACIP is shown in Table 412,21. The following information is specific to each of the vaccine-preventable illnesses of concern in adults.12,13,22

Seasonal Influenza

The options to protect the adult patient against seasonal influenza are a trivalent, inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV; Fluzone, high-dose Fluzone for adults ages 65 and older, Fluvirin, Fluarix, FluLaval, Afluria, Agriflu) or a live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV; FluMist).2,23 Dosage of TIV for adults is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid once annually. For adults ages 49 and younger, LAIV is administered at 0.2 mL intranasally, once per year.

ACIP now recommends universal influenza vaccination for all persons ages 6 months and older with no contraindications.2,8 Strong consideration should be given to concurrent administration of influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine to high-risk persons not previously vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.12

Note: When influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are given at the same time, they should be administered in opposite arms to reduce the risk of adverse reactions or a decreased antibody response to either vaccine.18,19

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV)

Pneumovax 2319 is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid or subcutaneously in the upper arm. The vaccine is recommended for8,19,24:

• Adults ages 65 and older who have not been previously vaccinated

• Adults now 65 and older who received PPSV vaccine at least five years ago and were younger than 65 at that time

• Adults ages 19 through 64 years who have asthma or who smoke24

• Any adult with the following underlying medical conditions: chronic heart or lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, cochlear implants, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic alcoholism, functional or anatomic asplenia, and immunocompromising conditions (HIV infection, diseases that require immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy; congenital immunodeficiency).24

A one-time revaccination is recommended after five years for persons ages 19 to 64 who have chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, or functional or anatomic asplenia, and for those who are immunocompromised.24

Note: According to the manufacturer of Zostavax18 and Pneumovax,23,19 these vaccines should not be given at the same time, as research has shown that Zostavax immunogenicity is reduced as a result.18-20

Zoster

For adults ages 60 and older, Zostavax18 is administered in a single 0.65-mL dose, subcutaneously in the upper arm. Providers are not required to ask about varicella vaccination history or history of varicella disease before administering the vaccine. Adults ages 60 and older who have previously had shingles can still be vaccinated during a routine health care visit.10,21,22

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (most commonly, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Any adult patient who has close household or occupational contact with persons at risk for severe varicella (eg, infants) need not take precautions after receiving the zoster vaccine, except in the rare case in which a varicella-like rash develops.10,21,22

Note: Review the note appearing in “Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV),” above, regarding coadministration of Zostavax and Pneumovax 23.18-20

Varicella

Adults who were born in the US before 1980 are considered immune to varicella and don’t need to be vaccinated, with the exception of health care workers, pregnant women, and immunocompromised persons. Nonimmune healthy adults who have not previously undergone vaccination should receive two 0.5-mL doses of Varivax, administered subcutaneously, four to eight weeks apart.25

Immunization is contraindicated in adults with a previous anaphylactic reaction to neomycin or gelatin, although a nonanaphylactic reaction to neomycin (eg, contact dermatitis) is not considered a contraindication.8

Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR)

The MMR vaccine is administered at 0.5 mL, given subcutaneously in the posterolateral fat of the upper arm.8

MMR-susceptible adults who were born during or since 1957 and are not at increased risk (see below) need only one dose of the MMR vaccine; those considered at increased risk need two doses, and a second dose can also be considered during an outbreak. Adults who require two doses should wait at least four weeks between the first and second doses.12

The following factors place adults at increased risk for MMR:

• Anticipated international travel

• Being a student in a post–secondary educational setting

• Working in a health care facility

• Recent exposure to measles, or an outbreak of measles or mumps

• Previous vaccination with killed measles vaccine

• Previous vaccination with an unknown measles vaccine between 1963 and 1967.

Also at risk are health care workers born before 1957 who have no evidence of immunity, and women who plan to become pregnant and have no evidence of immunity.8,12

Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis

Options for adults include a vaccine against tetanus and diphtheria (Td; Decavac); or a vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap; Adacel, Boostrix). Adults who have not been previously vaccinated should receive one dose of Tdap and two doses of Td (the first, one month after Tdap; the second at six to 12 months after the Tdap). Each is administered as a 0.5-mL dose IM in the deltoid. A booster dose is recommended every 10 years but can be given earlier in patients who sustain wounds or who anticipate international travel.8,12

Adults ages 19 through 64 should receive a single dose of Tdap in place of a booster dose if the last Td dose was administered at least 10 years earlier and the patient has not previously received Tdap. Additionally, a dose of Tdap (if not previously given) is recommended for postpartum women, close contacts of infants younger than 12 months, and all health care workers with direct patient contact. An interval as short as two years from the last Td is suggested; shorter intervals may be appropriate.8,12

According to the new 2011 recommendations, persons ages 65 and older who have close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should be vaccinated with Tdap, and any person age 65 or older may be vaccinated with Tdap. Also added is a recommendation to administer Tdap, regardless of the interval since the patient received his or her most recent Td-containing vaccine.8,12

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Gardasil26 protects both female and male patients against HPV infection; Cervarix27 is indicated only for female patients. Either quadrivalent vaccine or bivalent vaccine is recommended for female patients.12

In women ages 26 and younger, Gardasil (0.5 mL IM, administered in the deltoid at 0 month, 2 months, and 6 months) provides protection against diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (including cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancer caused by HPV types 16 and 18). In men ages 26 and younger, Gardasil provides protection against genital warts caused by HPV types 6 and 11.26

Cervarix,27 administered at 0 month, 1 month, and 6 months (0.5 mL IM in the deltoid), provides protection for women ages 25 and younger against cervical cancer and precancerous lesions caused by HPV types 16 and 18.

Caution: Patients should be advised to sit or lie down when the HPV vaccine is administered, and they should be observed for the subsequent 15 minutes. Syncope can occur after vaccination—most commonly among adolescents and young adults.28 Convulsive syncope has been reported.

Meningococcal Disease

Two vaccines are available to protect against meningococcal disease: Menactra29 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 polysaccharide diphtheria toxoids conjugate vaccine); and Menveo30 (meningococcal groups A, C, Y, and W-135 oligosaccharide diphtheria CRM197 conjugate vaccine). Both are administered in the deltoid, 0.5 mL IM.

The following patients should be considered for vaccination:

• College freshmen living in dormitories, as well as college students with immune deficiencies, as they are at higher risk for meningococcal disease

• Patients who travel to or reside in countries in which Neisseria meningitidis is epidemic (particularly those with the potential for prolonged contact with the local population)

• Travelers to Saudi Arabia for pilgrimage to Mecca (the Hajj)

• Patients with anatomical or functional asplenia (two-dose series).

A two-dose series of meningococcal conjugate vaccine is also recommended for adults with persistent complement component deficiencies, and for those with HIV infection who are vaccinated.12

Hepatitis A

Two hepatitis A vaccines (both inactivated) can be used interchangeably: Havrix31 and Vaqta.32 Dosing for both vaccines in 18-year-old patients is 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0 months, then at 6 to 12 months. In patients ages 19 and older, administration is the same, with the exception of increased dosing (1.0 mL IM).

Vaccination against hepatitis A is recommended for men who have sex with men, and for all adult patients who12:

• Travel to or work in areas where risk for hepatitis A transmission is high (especially those who take frequent trips or experience prolonged stays)

• Use injection drugs

• Have chronic liver disease

• Receive clotting factor concentrates for treatment of a blood-clotting disorder

• May have been exposed to hepatitis A in the previous two weeks

• Wish to be vaccinated against hepatitis A to avoid future infection.

Hepatitis B

Recombivax HB33 and Engerix-B34 are the two vaccines available to protect patients against hepatitis B (HBV), and they can be used interchangeably.12 In patients from birth through age 19, Recombivax HB33 or Engerix-B34 is given as 0.5 mL IM in the deltoid at 0, 1, and 6 months; patients ages 20 and older receive an increased dose (1.0 mL IM), with administration otherwise the same. According to the manufacturer of Recombivax HB,33 patients age 11 through 15 may be given either three doses of 0.5 mL or two doses of 1.0 mL.

The following adults are advised to undergo vaccination for HBV:

• At-risk, unvaccinated adults

• Those requesting protection against HBV infection

• Those planning to travel to areas where HBV is common

• Household contacts of a patient with chronic HBV infection, and sexual partners of a patient with HBV infection

• Adults with chronic liver disease

• Men who have sex with men

• Sexually active adults who are not in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship

• Adults who are being evaluated or treated for a sexually transmitted disease, including HIV infection

• Health care or public safety workers who may be exposed to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids

• Workers and residents in facilities for developmentally disabled persons

• Patients undergoing or anticipating dialysis

• Adults who inject illegal drugs or who have done so recently.12

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS FOR VACCINES COMMONLY USED IN ADULTS

See Table 5,8,22 for a summary of contraindications and precautions from ACIP and the Immunization Action Coalition that are associated with vaccinations mentioned in this article. A more complete summary can be found at www.im munize.org/catg.d/p3072a.pdf.

Conclusion

The adult patient’s vaccination status should be addressed at each health care encounter, and current recommendations should be followed. The duration of efficacy for vaccines is not an exact science. Many vaccines licensed in the US are relatively new, and recommendations for boosters for some of these vaccines will be forthcoming as more data are gathered. For example, the recommendation that a booster dose of Tdap be given to adults resulted from the recent increase in reported pertussis cases.35

Providers armed with the most current information and resources represent the forefront in ensuring that the US adult population is adequately immunized.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Immunization surveillance, assessment, and monitoring (2010). www.who.int/immunization_monitor ing/en. Accessed May 12, 2011.

2. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-08);1-62.

3. Schaffner W. Update on vaccine-preventable diseases: are adults in your community adequately protected? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4 suppl):S1-S11.

4. CDC. Healthy People 2010: Objectives for Improving Health. www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed May 6, 2011.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Developing Healthy People 2020: immunization and infectious diseases. www.healthy people.gov/2020. Accessed May 12, 2011.

6. Lu PJ, Nuorti JP. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among adults aged 65 years and older, United States, 1989-2008. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):287-295.

7. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Community immunity (“herd” immunity) (2010). www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/pages/communityimmunity.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2011.

8. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ADIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

9. High KP. Overcoming barriers to adult immunization. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(6): 525-528.

10. CDC; Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, eds. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (Pink Book). 12th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, 2011.

11. CDC. Vaccine-preventable diseases: improving vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults: a report on recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-8):1-15.

12. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

13. Thompson RF. Travel & Routine Immunizations: A Practical Guide for the Medical Office. 19th ed. Milwaukee, WI: Shoreland, Inc: 2001.