User login

Sick, or faking it?

CASE Vague symptoms; no clear etiology

Mr. W, age 53, presents to the emergency department (ED) describing acute mid-sternal chest pain (severity: 8 out of 10). His medical history is significant for pulmonary embolism and ascending aortic aneurysm in the context of Takayasu’s arteritis, an inflammatory condition of the large arterial blood vessels characterized by lesions that can lead to vascular stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm. Takayasu’s arteritis is also known as pulseless disease due to the weak or absent pulses the condition produces.

A review of Mr. W’s medical records reveals that this is his 23rd visit to this hospital within a year; the year before that, he had 22 visits. At each of these previous visits, he had similar vague symptoms, including dizziness, chest pain, lightheadedness, fainting, bilateral knee weakness, and left-arm numbness/weakness, and no clear acute etiology for his reported symptoms. Each time, after the treating clinicians ruled out possible acute complications of a flare-up of Takayasu’s arteritis through a physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, Mr. W was discharged with recommendations that he follow-up with his primary care physician and specialists. At each discharge, he would leave the hospital with hesitation.

At this present visit, the ED physician recognizes Mr. W as someone who visits the ED often with no profound acute issues, and reviews the substantial medical records available to the hospital. He suspects Mr. W is feigning symptoms, and orders a psychiatric consultation.

EVALUATION Psychiatric interview and mental status exam

On examination, Mr. W is not in acute distress. Despite reporting an 8 out of 10 for chest pain severity, he displays no psychomotor agitation, and his pulse rate and blood pressure are within normal limits. He makes appropriate eye contact and describes his mood as “great.” He reports no problems with sleep, appetite, or disinterest in pleasurable activities, and denies being depressed or having any symptoms consistent with a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or psychosis. He denies a history of panic attacks or excessive worrying that interferes with his sleep or activities of daily living. Additionally, Mr. W describes a stable, peaceful, and stress-free life within the limitations of his Takayasu’s arteritis, which he has been managing well since his diagnosis 6 years earlier.

Mr. W denies having any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs/fears that would be considered delusional, and he has no previous legal issues aside from an occasional driving citation. During the assessment, his affect remains broad and he denies having thoughts of suicide or homicide, or auditory or visual hallucinations.

Mr. W’s drug screen results are negative, and he denies using any illicit drugs. He uses only the medications that are prescribed by his clinicians. Overall, he seems to be a well-functioning individual. Mr. W reports that work is generally not stressful.

When the psychiatric team asks him about his frequent hospitalizations and ED visits, Mr. W is insistent that he is “just doing what my doctors said for me to do.” He repeats that he does not have any mental illness and did not see the point of seeing a psychiatrist.

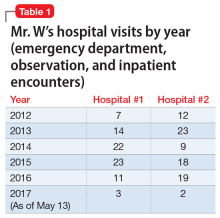

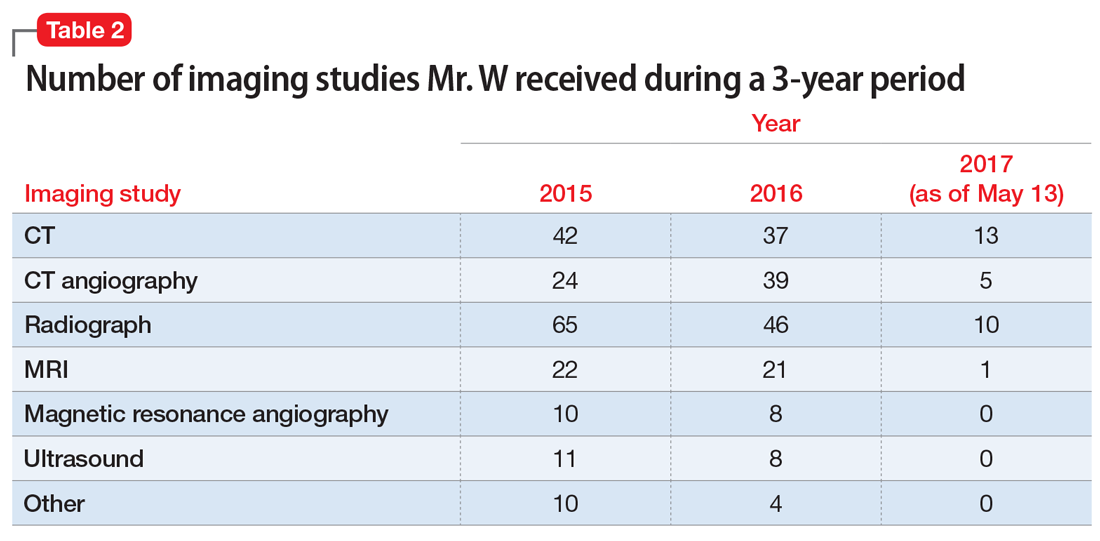

In pursuit of collateral information, the psychiatry team accesses a regional medical record database that allows registered medical institutions and practices to track patients’ medical encounters within the region. According to this database, within approximately 5.5 years, Mr. W had 163 clinical encounters (ED visits and inpatient admissions) and 376 radiological studies in our region (Table 1 and Table 2).

[polldaddy:10394110]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

The psychiatry team’s investigation of Mr. W’s medical records revealed the extent of his care-seeking behavior, and provided evidence for a diagnosis of factitious disorder.

Factitious disorder is an elusive psychiatric condition in which an individual chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Although its exact cause has not been fully deciphered, it is seen mostly among individuals with knowledge of the workings of the medical field, such as a health care worker.1 Factitious disorder is taxing on the health care system, with an estimated cost in the thousands of dollars per patient visit.2 The condition has an estimated prevalence of 0.8% to 1.0% of patients seen by psychiatric consult services3 and is reported to be more prevalent among women than men.1 Its cardinal features include health care site hopping and hospital shopping, vagueness about the patient’s history and symptoms, and discrepancy among reported symptoms, the patient’s behaviors, and objective clinical findings.4,5 Although not all patients with factitious disorder have a legitimate medical reason for seeking care, some individuals with an established medical diagnosis use their condition as a tool to chronically seek care and play the sick role.

Factitious disorder should not be confused with malingering, which is differentiated by the patient’s search for a secondary gain, such as financial reward or avoiding jail; or conversion disorder, which is marked by true physical or neurologic symptoms and clinical findings triggered by psychological stressors. Patients with factitious disorder usually are cooperative during hospital stays and resume their normal daily routine shortly after discharge.4 In this case, Mr. W denied any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs or fears that would be considered delusional. He had no previous or pending legal issues, which ruled out malingering to avoid legal repercussions.

Mr. W’s presentation was complicated by his Takayasu’s arteritis diagnosis. Because Takayasu’s arteritis has a serious list of potential complications, ED physicians have a low threshold for ordering diagnostic studies for a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis who presents with a chief complaint of chest pain. In other words, when a patient with this condition presents to an acute setting (such as the ED) with chest pain, his/her chief complaint is taken with extreme seriousness. Conventional angiography is the standard diagnostic tool for Takayasu’s arteritis; CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography are used for monitoring the disease’s progression.6

[polldaddy:10394113]

The authors’ observations

Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments for factitious disorder, and patients with this condition generally are resistant to psychiatric and/or psychological care when discovered and offered treatment.7 Among those who consent to psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy, which have shown some efficacy for the condition, the dropout rate is high.8

Continue to: Although the instinctive approach...

Although the instinctive approach is to confront the patient once the deception has been uncovered, expert recommendations are contradictory. Some recommend confrontation as part of a treatment protocol,8 while others advise against such an approach.9

Because of how often patients with factitious disorder seek medical care, secondary iatrogenic consequences are possible. For example, for years, Mr. W has been unknowingly exposing himself to the iatrogenic consequences of the cumulative effect of diagnostic imaging for years. In 3 years alone, Mr. W had undergone an average of 125 diagnostic imaging studies per year—with and without contrast—and many unnecessary rounds of treatment with steroids and other interventions known to have secondary iatrogenic consequences.10 Excessive radiation exposure is known to be carcinogenic over time,10 and excessive use of steroids is associated with weight gain, physical habitus changes, and increased risk of infections.11 In addition, the renal effects of the contrast materials from repeated imaging studies over so many years on Mr. W’s future kidney function are unknown.

TREATMENT Psychoeducation and referral for psychotherapy

We counsel Mr. W about factitious disorder and the risks of excessive hospitalizations, and refer him for follow-up at our local psychiatric clinic, as well as for individual psychotherapy. Mr. W is discharged because his medical work-up does not reveal any significant acute medical issues.

The authors’ observations

Because of the poor insight associated with factitious disorder and the limited treatment options available, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own. The prognosis for a patient with factitious disorder remains poor unless the patient is forced into treatment. More intervention-focused research is needed to help improve outcomes for patients with factitious disorder.

OUTCOME Failure to follow up

Mr. W fails to attend individual psychotherapy as recommended. According to our regional record database, Mr. W continues to present to other EDs regularly.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

A patient with factitious disorder stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Treatment options include psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy. However, due to poor insight, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own.

Related Resources

- Yates GP, Feldman MD. Factitious disorder: a systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:20-28.

- Galli S, Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J, et al. Conversion, factitious disorder and malingering: a distinct pattern or a continuum? Front Neurol Neurosci. 2018;42:72-80.

1. Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1163-1168.

2. Hoertel N, Lavaud P, Le Strat Y, et al. Estimated cost of a factitious disorder with 6-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2):1077-1078.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Psychosomatic medicine; factitious disorder. In: Pataki CS, Sussman N, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:34-45.

4 . Savino AC, Fordtran JS. Factitious disease: clinical lessons from case studies at Baylor University Medical Center. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2006;19(3):195-208.

5. Burnel A. Recognition and management of factitious disorder. Prescriber. 2015;26(21):37-39.

6. Duftner C, Dejaco C, Sepriano A, et al. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000612. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000612.

7. Jafferany M, Khalid Z, McDonald KA, et al. Psychological aspects of factitious disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(1). doi: 10.4088/PCC.17nr02229.

8. Bolat N, Yalçin O. Factitious disorder presenting with stuttering in two adolescents: the importance of psychoeducation. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2017;54(1):87-89.

9. Eisendrath SJ. Factitious physical disorders. West J Med. 1994;160(2):177-179.

10. Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251(1):175-184.

11. Oray M, Abu Samra K, Ebrahimiadib N, et al. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(4):457-465.

CASE Vague symptoms; no clear etiology

Mr. W, age 53, presents to the emergency department (ED) describing acute mid-sternal chest pain (severity: 8 out of 10). His medical history is significant for pulmonary embolism and ascending aortic aneurysm in the context of Takayasu’s arteritis, an inflammatory condition of the large arterial blood vessels characterized by lesions that can lead to vascular stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm. Takayasu’s arteritis is also known as pulseless disease due to the weak or absent pulses the condition produces.

A review of Mr. W’s medical records reveals that this is his 23rd visit to this hospital within a year; the year before that, he had 22 visits. At each of these previous visits, he had similar vague symptoms, including dizziness, chest pain, lightheadedness, fainting, bilateral knee weakness, and left-arm numbness/weakness, and no clear acute etiology for his reported symptoms. Each time, after the treating clinicians ruled out possible acute complications of a flare-up of Takayasu’s arteritis through a physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, Mr. W was discharged with recommendations that he follow-up with his primary care physician and specialists. At each discharge, he would leave the hospital with hesitation.

At this present visit, the ED physician recognizes Mr. W as someone who visits the ED often with no profound acute issues, and reviews the substantial medical records available to the hospital. He suspects Mr. W is feigning symptoms, and orders a psychiatric consultation.

EVALUATION Psychiatric interview and mental status exam

On examination, Mr. W is not in acute distress. Despite reporting an 8 out of 10 for chest pain severity, he displays no psychomotor agitation, and his pulse rate and blood pressure are within normal limits. He makes appropriate eye contact and describes his mood as “great.” He reports no problems with sleep, appetite, or disinterest in pleasurable activities, and denies being depressed or having any symptoms consistent with a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or psychosis. He denies a history of panic attacks or excessive worrying that interferes with his sleep or activities of daily living. Additionally, Mr. W describes a stable, peaceful, and stress-free life within the limitations of his Takayasu’s arteritis, which he has been managing well since his diagnosis 6 years earlier.

Mr. W denies having any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs/fears that would be considered delusional, and he has no previous legal issues aside from an occasional driving citation. During the assessment, his affect remains broad and he denies having thoughts of suicide or homicide, or auditory or visual hallucinations.

Mr. W’s drug screen results are negative, and he denies using any illicit drugs. He uses only the medications that are prescribed by his clinicians. Overall, he seems to be a well-functioning individual. Mr. W reports that work is generally not stressful.

When the psychiatric team asks him about his frequent hospitalizations and ED visits, Mr. W is insistent that he is “just doing what my doctors said for me to do.” He repeats that he does not have any mental illness and did not see the point of seeing a psychiatrist.

In pursuit of collateral information, the psychiatry team accesses a regional medical record database that allows registered medical institutions and practices to track patients’ medical encounters within the region. According to this database, within approximately 5.5 years, Mr. W had 163 clinical encounters (ED visits and inpatient admissions) and 376 radiological studies in our region (Table 1 and Table 2).

[polldaddy:10394110]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

The psychiatry team’s investigation of Mr. W’s medical records revealed the extent of his care-seeking behavior, and provided evidence for a diagnosis of factitious disorder.

Factitious disorder is an elusive psychiatric condition in which an individual chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Although its exact cause has not been fully deciphered, it is seen mostly among individuals with knowledge of the workings of the medical field, such as a health care worker.1 Factitious disorder is taxing on the health care system, with an estimated cost in the thousands of dollars per patient visit.2 The condition has an estimated prevalence of 0.8% to 1.0% of patients seen by psychiatric consult services3 and is reported to be more prevalent among women than men.1 Its cardinal features include health care site hopping and hospital shopping, vagueness about the patient’s history and symptoms, and discrepancy among reported symptoms, the patient’s behaviors, and objective clinical findings.4,5 Although not all patients with factitious disorder have a legitimate medical reason for seeking care, some individuals with an established medical diagnosis use their condition as a tool to chronically seek care and play the sick role.

Factitious disorder should not be confused with malingering, which is differentiated by the patient’s search for a secondary gain, such as financial reward or avoiding jail; or conversion disorder, which is marked by true physical or neurologic symptoms and clinical findings triggered by psychological stressors. Patients with factitious disorder usually are cooperative during hospital stays and resume their normal daily routine shortly after discharge.4 In this case, Mr. W denied any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs or fears that would be considered delusional. He had no previous or pending legal issues, which ruled out malingering to avoid legal repercussions.

Mr. W’s presentation was complicated by his Takayasu’s arteritis diagnosis. Because Takayasu’s arteritis has a serious list of potential complications, ED physicians have a low threshold for ordering diagnostic studies for a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis who presents with a chief complaint of chest pain. In other words, when a patient with this condition presents to an acute setting (such as the ED) with chest pain, his/her chief complaint is taken with extreme seriousness. Conventional angiography is the standard diagnostic tool for Takayasu’s arteritis; CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography are used for monitoring the disease’s progression.6

[polldaddy:10394113]

The authors’ observations

Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments for factitious disorder, and patients with this condition generally are resistant to psychiatric and/or psychological care when discovered and offered treatment.7 Among those who consent to psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy, which have shown some efficacy for the condition, the dropout rate is high.8

Continue to: Although the instinctive approach...

Although the instinctive approach is to confront the patient once the deception has been uncovered, expert recommendations are contradictory. Some recommend confrontation as part of a treatment protocol,8 while others advise against such an approach.9

Because of how often patients with factitious disorder seek medical care, secondary iatrogenic consequences are possible. For example, for years, Mr. W has been unknowingly exposing himself to the iatrogenic consequences of the cumulative effect of diagnostic imaging for years. In 3 years alone, Mr. W had undergone an average of 125 diagnostic imaging studies per year—with and without contrast—and many unnecessary rounds of treatment with steroids and other interventions known to have secondary iatrogenic consequences.10 Excessive radiation exposure is known to be carcinogenic over time,10 and excessive use of steroids is associated with weight gain, physical habitus changes, and increased risk of infections.11 In addition, the renal effects of the contrast materials from repeated imaging studies over so many years on Mr. W’s future kidney function are unknown.

TREATMENT Psychoeducation and referral for psychotherapy

We counsel Mr. W about factitious disorder and the risks of excessive hospitalizations, and refer him for follow-up at our local psychiatric clinic, as well as for individual psychotherapy. Mr. W is discharged because his medical work-up does not reveal any significant acute medical issues.

The authors’ observations

Because of the poor insight associated with factitious disorder and the limited treatment options available, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own. The prognosis for a patient with factitious disorder remains poor unless the patient is forced into treatment. More intervention-focused research is needed to help improve outcomes for patients with factitious disorder.

OUTCOME Failure to follow up

Mr. W fails to attend individual psychotherapy as recommended. According to our regional record database, Mr. W continues to present to other EDs regularly.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

A patient with factitious disorder stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Treatment options include psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy. However, due to poor insight, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own.

Related Resources

- Yates GP, Feldman MD. Factitious disorder: a systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:20-28.

- Galli S, Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J, et al. Conversion, factitious disorder and malingering: a distinct pattern or a continuum? Front Neurol Neurosci. 2018;42:72-80.

CASE Vague symptoms; no clear etiology

Mr. W, age 53, presents to the emergency department (ED) describing acute mid-sternal chest pain (severity: 8 out of 10). His medical history is significant for pulmonary embolism and ascending aortic aneurysm in the context of Takayasu’s arteritis, an inflammatory condition of the large arterial blood vessels characterized by lesions that can lead to vascular stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm. Takayasu’s arteritis is also known as pulseless disease due to the weak or absent pulses the condition produces.

A review of Mr. W’s medical records reveals that this is his 23rd visit to this hospital within a year; the year before that, he had 22 visits. At each of these previous visits, he had similar vague symptoms, including dizziness, chest pain, lightheadedness, fainting, bilateral knee weakness, and left-arm numbness/weakness, and no clear acute etiology for his reported symptoms. Each time, after the treating clinicians ruled out possible acute complications of a flare-up of Takayasu’s arteritis through a physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, Mr. W was discharged with recommendations that he follow-up with his primary care physician and specialists. At each discharge, he would leave the hospital with hesitation.

At this present visit, the ED physician recognizes Mr. W as someone who visits the ED often with no profound acute issues, and reviews the substantial medical records available to the hospital. He suspects Mr. W is feigning symptoms, and orders a psychiatric consultation.

EVALUATION Psychiatric interview and mental status exam

On examination, Mr. W is not in acute distress. Despite reporting an 8 out of 10 for chest pain severity, he displays no psychomotor agitation, and his pulse rate and blood pressure are within normal limits. He makes appropriate eye contact and describes his mood as “great.” He reports no problems with sleep, appetite, or disinterest in pleasurable activities, and denies being depressed or having any symptoms consistent with a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or psychosis. He denies a history of panic attacks or excessive worrying that interferes with his sleep or activities of daily living. Additionally, Mr. W describes a stable, peaceful, and stress-free life within the limitations of his Takayasu’s arteritis, which he has been managing well since his diagnosis 6 years earlier.

Mr. W denies having any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs/fears that would be considered delusional, and he has no previous legal issues aside from an occasional driving citation. During the assessment, his affect remains broad and he denies having thoughts of suicide or homicide, or auditory or visual hallucinations.

Mr. W’s drug screen results are negative, and he denies using any illicit drugs. He uses only the medications that are prescribed by his clinicians. Overall, he seems to be a well-functioning individual. Mr. W reports that work is generally not stressful.

When the psychiatric team asks him about his frequent hospitalizations and ED visits, Mr. W is insistent that he is “just doing what my doctors said for me to do.” He repeats that he does not have any mental illness and did not see the point of seeing a psychiatrist.

In pursuit of collateral information, the psychiatry team accesses a regional medical record database that allows registered medical institutions and practices to track patients’ medical encounters within the region. According to this database, within approximately 5.5 years, Mr. W had 163 clinical encounters (ED visits and inpatient admissions) and 376 radiological studies in our region (Table 1 and Table 2).

[polldaddy:10394110]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

The psychiatry team’s investigation of Mr. W’s medical records revealed the extent of his care-seeking behavior, and provided evidence for a diagnosis of factitious disorder.

Factitious disorder is an elusive psychiatric condition in which an individual chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Although its exact cause has not been fully deciphered, it is seen mostly among individuals with knowledge of the workings of the medical field, such as a health care worker.1 Factitious disorder is taxing on the health care system, with an estimated cost in the thousands of dollars per patient visit.2 The condition has an estimated prevalence of 0.8% to 1.0% of patients seen by psychiatric consult services3 and is reported to be more prevalent among women than men.1 Its cardinal features include health care site hopping and hospital shopping, vagueness about the patient’s history and symptoms, and discrepancy among reported symptoms, the patient’s behaviors, and objective clinical findings.4,5 Although not all patients with factitious disorder have a legitimate medical reason for seeking care, some individuals with an established medical diagnosis use their condition as a tool to chronically seek care and play the sick role.

Factitious disorder should not be confused with malingering, which is differentiated by the patient’s search for a secondary gain, such as financial reward or avoiding jail; or conversion disorder, which is marked by true physical or neurologic symptoms and clinical findings triggered by psychological stressors. Patients with factitious disorder usually are cooperative during hospital stays and resume their normal daily routine shortly after discharge.4 In this case, Mr. W denied any psychiatric symptoms, apprehensive feelings, or beliefs or fears that would be considered delusional. He had no previous or pending legal issues, which ruled out malingering to avoid legal repercussions.

Mr. W’s presentation was complicated by his Takayasu’s arteritis diagnosis. Because Takayasu’s arteritis has a serious list of potential complications, ED physicians have a low threshold for ordering diagnostic studies for a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis who presents with a chief complaint of chest pain. In other words, when a patient with this condition presents to an acute setting (such as the ED) with chest pain, his/her chief complaint is taken with extreme seriousness. Conventional angiography is the standard diagnostic tool for Takayasu’s arteritis; CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography are used for monitoring the disease’s progression.6

[polldaddy:10394113]

The authors’ observations

Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments for factitious disorder, and patients with this condition generally are resistant to psychiatric and/or psychological care when discovered and offered treatment.7 Among those who consent to psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy, which have shown some efficacy for the condition, the dropout rate is high.8

Continue to: Although the instinctive approach...

Although the instinctive approach is to confront the patient once the deception has been uncovered, expert recommendations are contradictory. Some recommend confrontation as part of a treatment protocol,8 while others advise against such an approach.9

Because of how often patients with factitious disorder seek medical care, secondary iatrogenic consequences are possible. For example, for years, Mr. W has been unknowingly exposing himself to the iatrogenic consequences of the cumulative effect of diagnostic imaging for years. In 3 years alone, Mr. W had undergone an average of 125 diagnostic imaging studies per year—with and without contrast—and many unnecessary rounds of treatment with steroids and other interventions known to have secondary iatrogenic consequences.10 Excessive radiation exposure is known to be carcinogenic over time,10 and excessive use of steroids is associated with weight gain, physical habitus changes, and increased risk of infections.11 In addition, the renal effects of the contrast materials from repeated imaging studies over so many years on Mr. W’s future kidney function are unknown.

TREATMENT Psychoeducation and referral for psychotherapy

We counsel Mr. W about factitious disorder and the risks of excessive hospitalizations, and refer him for follow-up at our local psychiatric clinic, as well as for individual psychotherapy. Mr. W is discharged because his medical work-up does not reveal any significant acute medical issues.

The authors’ observations

Because of the poor insight associated with factitious disorder and the limited treatment options available, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own. The prognosis for a patient with factitious disorder remains poor unless the patient is forced into treatment. More intervention-focused research is needed to help improve outcomes for patients with factitious disorder.

OUTCOME Failure to follow up

Mr. W fails to attend individual psychotherapy as recommended. According to our regional record database, Mr. W continues to present to other EDs regularly.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

A patient with factitious disorder stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient. Treatment options include psychiatric care, psychoeducation, or psychotherapy. However, due to poor insight, a patient with factitious disorder is unlikely to enter psychiatric treatment on his/her own.

Related Resources

- Yates GP, Feldman MD. Factitious disorder: a systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:20-28.

- Galli S, Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J, et al. Conversion, factitious disorder and malingering: a distinct pattern or a continuum? Front Neurol Neurosci. 2018;42:72-80.

1. Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1163-1168.

2. Hoertel N, Lavaud P, Le Strat Y, et al. Estimated cost of a factitious disorder with 6-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2):1077-1078.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Psychosomatic medicine; factitious disorder. In: Pataki CS, Sussman N, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:34-45.

4 . Savino AC, Fordtran JS. Factitious disease: clinical lessons from case studies at Baylor University Medical Center. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2006;19(3):195-208.

5. Burnel A. Recognition and management of factitious disorder. Prescriber. 2015;26(21):37-39.

6. Duftner C, Dejaco C, Sepriano A, et al. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000612. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000612.

7. Jafferany M, Khalid Z, McDonald KA, et al. Psychological aspects of factitious disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(1). doi: 10.4088/PCC.17nr02229.

8. Bolat N, Yalçin O. Factitious disorder presenting with stuttering in two adolescents: the importance of psychoeducation. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2017;54(1):87-89.

9. Eisendrath SJ. Factitious physical disorders. West J Med. 1994;160(2):177-179.

10. Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251(1):175-184.

11. Oray M, Abu Samra K, Ebrahimiadib N, et al. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(4):457-465.

1. Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1163-1168.

2. Hoertel N, Lavaud P, Le Strat Y, et al. Estimated cost of a factitious disorder with 6-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2):1077-1078.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Psychosomatic medicine; factitious disorder. In: Pataki CS, Sussman N, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:34-45.

4 . Savino AC, Fordtran JS. Factitious disease: clinical lessons from case studies at Baylor University Medical Center. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2006;19(3):195-208.

5. Burnel A. Recognition and management of factitious disorder. Prescriber. 2015;26(21):37-39.

6. Duftner C, Dejaco C, Sepriano A, et al. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000612. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000612.

7. Jafferany M, Khalid Z, McDonald KA, et al. Psychological aspects of factitious disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(1). doi: 10.4088/PCC.17nr02229.

8. Bolat N, Yalçin O. Factitious disorder presenting with stuttering in two adolescents: the importance of psychoeducation. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2017;54(1):87-89.

9. Eisendrath SJ. Factitious physical disorders. West J Med. 1994;160(2):177-179.

10. Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251(1):175-184.

11. Oray M, Abu Samra K, Ebrahimiadib N, et al. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(4):457-465.