User login

What are the adverse effects of prolonged opioid use in patients with chronic pain?

CONSTIPATION, NAUSEA, AND DYSPEPSIA are the most common long-term adverse effects of chronic opioid use (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of low-quality studies). Men may experience depression, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction (SOR: B, 2 observational studies). Prolonged use of opioids also may increase sensitivity to pain (SOR: C, review of case reports and case series). (This review does not address drug seeking or drug escalating.)

Patients on long-term methadone are at risk for cardiac arrhythmias caused by prolonged QT intervals and torsades de pointes (SOR: C, case reports).

Patients taking buprenorphine for opioid dependence may experience acute hepatitis (SOR: C, 1 case report).

Evidence summary

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain persisting longer than 3 months. Evidence of the efficacy of opioids for noncancer pain has led to increased opioid prescribing over the past 20 years and with it, growing concern about adverse effects from long-term use.1

Nausea, constipation, dyspepsia lead side-effects parade

A Cochrane systematic review of 26 studies (25 observational studies and 1 randomized controlled trial [RCT]) of adults who had taken opioids for noncancer pain for at least 6 months assessed the adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy.2 Although the authors couldn’t quantify the incidence of adverse effects because of inconsistent reporting and definition of effects, they stated that the most common complications were nausea, constipation, and dyspepsia. The review found that 22.9% of patients (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.3-32.8) discontinued oral opioids because of adverse effects.

A cross-sectional observational study evaluated self-reported adverse effects in 889 patients who received opioid therapy for noncancer pain lasting at least 3 months.3 Forty percent of patients reported constipation and 18% sexual dysfunction. Patients taking opioids daily experienced more constipation than patients taking the drugs intermittently (39% vs 24%; number needed to harm [NNH]=7; P<.05).

Sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression aren’t far behind

A case-control study of 20 male cancer survivors with neuropathic pain who took 200 mg of morphine-equivalent daily for a year found that 90% of patients in the opioid group experienced hypogonadism with symptoms of sexual dysfunction, fatigue, and depression, compared with 40% of the 20 controls (NNH=2; 95% CI, 1-5).4

A case-controlled observational study of 54 men with noncancer pain who took opioids for 1 year found that 39 of 45 men who had normal erectile function before opioid therapy reported severe erectile dysfunction while taking the drugs.5 Levels of testosterone and estradiol were significantly lower (P<.0001) in the men taking opioids than the 27 opioid-free controls.

Potentially fatal arrhythmias are a risk for some patients

From 1969 to 2002, 59 cases of QT prolongation or torsades de pointes in methadone users, 5 (8.5%) of them fatal, were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration’s Medwatch Database.6 The mean daily methadone dose was 410 mg (median dose 345 mg, range 29-1680 mg). Length of therapy was not reported. In 44 (75%) of reported cases, patients had other known risks for QT prolongation or torsades de pointes, including female sex, interacting medications, potassium or magnesium abnormalities, and structural heart disease.

Buprenorphine may cause acute hepatitis

No apparent long-term hepatic adverse effects are associated with chronic opioid use. However, a 2004 case series described acute cytolytic hepatitis in 7 patients taking buprenorphine, all with hepatitis C and a history of intravenous drug abuse.7 Acute symptoms resolved quickly in all cases, and only 3 patients required a reduction in buprenorphine dosage.

Prolonged use may increase sensitivity to pain

Case reports and case series have found that prolonged use of opioids causes increased sensitivity to pain in some patients, which is difficult to differentiate from opioid tolerance.8

Recommendations

The American Pain Society (APS) recommends anticipating, identifying, and treating opioid-related adverse effects such as constipation or nausea.1 APS advises against using opioid antagonists to prevent or treat bowel dysfunction, and encourages older patients or patients with an increased risk of developing constipation to start a bowel regimen. Patients with complaints suggesting hypogonadism should be tested for hormonal deficiencies.

The Center for Substance Abuse and Treatment recommends obtaining a cardiac history and an electrocardiogram (EKG) on all patients before starting methadone and repeating the EKG at 30 days and annually thereafter to evaluate for QT prolongation.9 Prescribers should also warn patients of the risk of methadone-induced arrhythmias and be aware of interacting medications that prolong the QT interval or reduce methadone elimination.

1. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Adler JA, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

2. Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006605.-

3. Brown RT, Zuelsdorff M, Fleming M. Adverse effects and cognitive function among primary care patients taking opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Opioid Manag. 2006;2:137-146.

4. Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, et al. Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with chronic exposure to opioids. Cancer. 2004;100:851-858.

5. Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3:377-384.

6. Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:747-753.

7. Hervé S, Riachi G, Noblet C, et al. Acute hepatitis due to buprenorphine administration. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1033-1037.

8. Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;20:1943-1953.

9. Krantz MJ, Martin J, Stimmel B, et al. QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:387-395.

CONSTIPATION, NAUSEA, AND DYSPEPSIA are the most common long-term adverse effects of chronic opioid use (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of low-quality studies). Men may experience depression, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction (SOR: B, 2 observational studies). Prolonged use of opioids also may increase sensitivity to pain (SOR: C, review of case reports and case series). (This review does not address drug seeking or drug escalating.)

Patients on long-term methadone are at risk for cardiac arrhythmias caused by prolonged QT intervals and torsades de pointes (SOR: C, case reports).

Patients taking buprenorphine for opioid dependence may experience acute hepatitis (SOR: C, 1 case report).

Evidence summary

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain persisting longer than 3 months. Evidence of the efficacy of opioids for noncancer pain has led to increased opioid prescribing over the past 20 years and with it, growing concern about adverse effects from long-term use.1

Nausea, constipation, dyspepsia lead side-effects parade

A Cochrane systematic review of 26 studies (25 observational studies and 1 randomized controlled trial [RCT]) of adults who had taken opioids for noncancer pain for at least 6 months assessed the adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy.2 Although the authors couldn’t quantify the incidence of adverse effects because of inconsistent reporting and definition of effects, they stated that the most common complications were nausea, constipation, and dyspepsia. The review found that 22.9% of patients (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.3-32.8) discontinued oral opioids because of adverse effects.

A cross-sectional observational study evaluated self-reported adverse effects in 889 patients who received opioid therapy for noncancer pain lasting at least 3 months.3 Forty percent of patients reported constipation and 18% sexual dysfunction. Patients taking opioids daily experienced more constipation than patients taking the drugs intermittently (39% vs 24%; number needed to harm [NNH]=7; P<.05).

Sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression aren’t far behind

A case-control study of 20 male cancer survivors with neuropathic pain who took 200 mg of morphine-equivalent daily for a year found that 90% of patients in the opioid group experienced hypogonadism with symptoms of sexual dysfunction, fatigue, and depression, compared with 40% of the 20 controls (NNH=2; 95% CI, 1-5).4

A case-controlled observational study of 54 men with noncancer pain who took opioids for 1 year found that 39 of 45 men who had normal erectile function before opioid therapy reported severe erectile dysfunction while taking the drugs.5 Levels of testosterone and estradiol were significantly lower (P<.0001) in the men taking opioids than the 27 opioid-free controls.

Potentially fatal arrhythmias are a risk for some patients

From 1969 to 2002, 59 cases of QT prolongation or torsades de pointes in methadone users, 5 (8.5%) of them fatal, were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration’s Medwatch Database.6 The mean daily methadone dose was 410 mg (median dose 345 mg, range 29-1680 mg). Length of therapy was not reported. In 44 (75%) of reported cases, patients had other known risks for QT prolongation or torsades de pointes, including female sex, interacting medications, potassium or magnesium abnormalities, and structural heart disease.

Buprenorphine may cause acute hepatitis

No apparent long-term hepatic adverse effects are associated with chronic opioid use. However, a 2004 case series described acute cytolytic hepatitis in 7 patients taking buprenorphine, all with hepatitis C and a history of intravenous drug abuse.7 Acute symptoms resolved quickly in all cases, and only 3 patients required a reduction in buprenorphine dosage.

Prolonged use may increase sensitivity to pain

Case reports and case series have found that prolonged use of opioids causes increased sensitivity to pain in some patients, which is difficult to differentiate from opioid tolerance.8

Recommendations

The American Pain Society (APS) recommends anticipating, identifying, and treating opioid-related adverse effects such as constipation or nausea.1 APS advises against using opioid antagonists to prevent or treat bowel dysfunction, and encourages older patients or patients with an increased risk of developing constipation to start a bowel regimen. Patients with complaints suggesting hypogonadism should be tested for hormonal deficiencies.

The Center for Substance Abuse and Treatment recommends obtaining a cardiac history and an electrocardiogram (EKG) on all patients before starting methadone and repeating the EKG at 30 days and annually thereafter to evaluate for QT prolongation.9 Prescribers should also warn patients of the risk of methadone-induced arrhythmias and be aware of interacting medications that prolong the QT interval or reduce methadone elimination.

CONSTIPATION, NAUSEA, AND DYSPEPSIA are the most common long-term adverse effects of chronic opioid use (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of low-quality studies). Men may experience depression, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction (SOR: B, 2 observational studies). Prolonged use of opioids also may increase sensitivity to pain (SOR: C, review of case reports and case series). (This review does not address drug seeking or drug escalating.)

Patients on long-term methadone are at risk for cardiac arrhythmias caused by prolonged QT intervals and torsades de pointes (SOR: C, case reports).

Patients taking buprenorphine for opioid dependence may experience acute hepatitis (SOR: C, 1 case report).

Evidence summary

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain persisting longer than 3 months. Evidence of the efficacy of opioids for noncancer pain has led to increased opioid prescribing over the past 20 years and with it, growing concern about adverse effects from long-term use.1

Nausea, constipation, dyspepsia lead side-effects parade

A Cochrane systematic review of 26 studies (25 observational studies and 1 randomized controlled trial [RCT]) of adults who had taken opioids for noncancer pain for at least 6 months assessed the adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy.2 Although the authors couldn’t quantify the incidence of adverse effects because of inconsistent reporting and definition of effects, they stated that the most common complications were nausea, constipation, and dyspepsia. The review found that 22.9% of patients (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.3-32.8) discontinued oral opioids because of adverse effects.

A cross-sectional observational study evaluated self-reported adverse effects in 889 patients who received opioid therapy for noncancer pain lasting at least 3 months.3 Forty percent of patients reported constipation and 18% sexual dysfunction. Patients taking opioids daily experienced more constipation than patients taking the drugs intermittently (39% vs 24%; number needed to harm [NNH]=7; P<.05).

Sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression aren’t far behind

A case-control study of 20 male cancer survivors with neuropathic pain who took 200 mg of morphine-equivalent daily for a year found that 90% of patients in the opioid group experienced hypogonadism with symptoms of sexual dysfunction, fatigue, and depression, compared with 40% of the 20 controls (NNH=2; 95% CI, 1-5).4

A case-controlled observational study of 54 men with noncancer pain who took opioids for 1 year found that 39 of 45 men who had normal erectile function before opioid therapy reported severe erectile dysfunction while taking the drugs.5 Levels of testosterone and estradiol were significantly lower (P<.0001) in the men taking opioids than the 27 opioid-free controls.

Potentially fatal arrhythmias are a risk for some patients

From 1969 to 2002, 59 cases of QT prolongation or torsades de pointes in methadone users, 5 (8.5%) of them fatal, were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration’s Medwatch Database.6 The mean daily methadone dose was 410 mg (median dose 345 mg, range 29-1680 mg). Length of therapy was not reported. In 44 (75%) of reported cases, patients had other known risks for QT prolongation or torsades de pointes, including female sex, interacting medications, potassium or magnesium abnormalities, and structural heart disease.

Buprenorphine may cause acute hepatitis

No apparent long-term hepatic adverse effects are associated with chronic opioid use. However, a 2004 case series described acute cytolytic hepatitis in 7 patients taking buprenorphine, all with hepatitis C and a history of intravenous drug abuse.7 Acute symptoms resolved quickly in all cases, and only 3 patients required a reduction in buprenorphine dosage.

Prolonged use may increase sensitivity to pain

Case reports and case series have found that prolonged use of opioids causes increased sensitivity to pain in some patients, which is difficult to differentiate from opioid tolerance.8

Recommendations

The American Pain Society (APS) recommends anticipating, identifying, and treating opioid-related adverse effects such as constipation or nausea.1 APS advises against using opioid antagonists to prevent or treat bowel dysfunction, and encourages older patients or patients with an increased risk of developing constipation to start a bowel regimen. Patients with complaints suggesting hypogonadism should be tested for hormonal deficiencies.

The Center for Substance Abuse and Treatment recommends obtaining a cardiac history and an electrocardiogram (EKG) on all patients before starting methadone and repeating the EKG at 30 days and annually thereafter to evaluate for QT prolongation.9 Prescribers should also warn patients of the risk of methadone-induced arrhythmias and be aware of interacting medications that prolong the QT interval or reduce methadone elimination.

1. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Adler JA, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

2. Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006605.-

3. Brown RT, Zuelsdorff M, Fleming M. Adverse effects and cognitive function among primary care patients taking opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Opioid Manag. 2006;2:137-146.

4. Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, et al. Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with chronic exposure to opioids. Cancer. 2004;100:851-858.

5. Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3:377-384.

6. Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:747-753.

7. Hervé S, Riachi G, Noblet C, et al. Acute hepatitis due to buprenorphine administration. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1033-1037.

8. Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;20:1943-1953.

9. Krantz MJ, Martin J, Stimmel B, et al. QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:387-395.

1. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Adler JA, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

2. Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006605.-

3. Brown RT, Zuelsdorff M, Fleming M. Adverse effects and cognitive function among primary care patients taking opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Opioid Manag. 2006;2:137-146.

4. Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, et al. Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with chronic exposure to opioids. Cancer. 2004;100:851-858.

5. Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3:377-384.

6. Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:747-753.

7. Hervé S, Riachi G, Noblet C, et al. Acute hepatitis due to buprenorphine administration. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1033-1037.

8. Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;20:1943-1953.

9. Krantz MJ, Martin J, Stimmel B, et al. QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:387-395.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly?

There is no one best evidence-based treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly. While the most common first-line treatments are dietary fiber and exercise, the evidence is insufficient to support this approach in the geriatric population (strength of recommendation [SOR]: for dietary fiber: A, based on a systematic review; for exercise: SOR: B, based on 1 good- and 1 fair-quality randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Herbal supplements (such as aloe), alternative treatments (biofeedback), lubricants (mineral oil), and combination laxatives sold in the US have not been sufficiently studied in controlled trials to make a recommendation (SOR: A, based on systematic review).

An abdominal kneading device can be used to treat chronic constipation, but the evidence is limited (SOR: B, based on 1 cohort study.)

Polyethylene glycol has not been studied in the elderly. A newer agent, lubiprostone (Amitiza), appears to be effective for the treatment of chronic constipation for elderly patients (SOR: B, based on subgroup analysis of RCTs.)

Is the patient truly constipated?

Mandi Sehgal, MD

Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, University of Cincinnati

Many older people feel that if they do not have a bowel movement every day they are constipated. However, constipation is defined as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week. So, the first thing we must do is to confirm that the patient is truly constipated.

Before I start my patients on any medicine, I suggest a trial of increased daily water and fiber intake along with exercise, followed by a trial of stool softeners and stimulant laxatives, if needed. If all of these methods fail, I consider trying polyethylene glycol, which can be titrated to effect. As with all medication use by the elderly, it is important to titrate cautiously (“start low and go slow”) and add other medications only when necessary.

Evidence summary

Few well-designed studies have focused on constipation treatment among the elderly. Our search located 1 systematic review of pharmacologic management, a systematic review of fiber management, 2 RCTs on the effect of exercise, and 1 before-after cohort study on abdominal massage. These studies were all conducted among geriatric patients with constipation. Two high-quality systematic reviews regarding chronic constipation management for adults of all ages included management options not studied in exclusively geriatric populations, such as herbal supplements, biofeedback, tegaserod, and polyethylene glycol.

Laxatives, fiber, and exercise: Studies are inconclusive

Two good-quality systematic reviews looked at 10 RCTs comparing laxatives with placebo, and 10 RCTs comparing 1 laxative with another.1,2 The studies generally had few participants, were of short duration, and were conducted in institutional settings. Most lacked power to make valid conclusions. These studies varied in the reported outcome measures, including stool frequency, stool consistency, straining, decrease in laxative use, and symptom scores. The reviews concluded that the best pharmacologic treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly has not been established.

Five of the higher-quality studies attained statistical significance. They showed a small but significant improvement in bowel movement frequency with a laxative when compared with placebo or another laxative (TABLE). The authors noted that multiple poor-quality studies have shown nonsignificant trends for improved constipation symptoms with laxatives compared with placebo.

Inconsistent findings on fiber. A good-quality systematic review3 of dietary fiber in the treatment of constipation for older patients located 8 moderate- to high-quality studies (6 RCTs and 2 blinded before-after studies), with 269 study participants in institutional settings. Results among studies were inconsistent, casting doubt on the efficacy of fiber treatment for constipation in the institutionalized elder.

Two RCTs4,5 investigating the effect of exercise on 246 institutionalized older patients showed no improvement in constipation. One study was of good quality, reporting adequate power and used an intention-to-treat analysis. The other was of fair quality.

Alternative TXs not well studied

A high-quality systematic review6 of constipation management among adults of all ages in North America found a lack of quality RCTs examining herbal supplement treatment. Biofeedback has been studied in adult populations, but no RCTs with placebo or sham-controls have been published.

One before-after cohort study7 investigated an external kneading mechanical device (Free-Lax) that was applied to the abdomen for 20 minutes once daily in 30 randomly selected chronically constipated nursing home residents. Researchers found significant improvements in bowel movement frequency, stool consistency and volume, and colonic transit time without side effects (TABLE).

A look beyond geriatric patients

Polyethylene glycol, tegaserod, and lubiprostone have not been studied in trials of exclusively geriatric populations. Two high-quality systematic reviews,6,8 including medium- to high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic management of chronic constipation, found good evidence to support treatment with polyethylene glycol and tegaserod in adults of all ages. Of the 8 RCTs looking at polyethylene glycol, only 1 of the studies—a high-quality crossover comparison of polyethylene glycol vs placebo with 37 out-patient subjects—included a population with a mean age >60 years (mean age 62, range 42–89 years).

TABLE

How well do these interventions work for older patients with chronic constipation?

| INTERVENTION VS COMPARISON | STOOL FREQUENCY (STOOLS PER WEEK) | NNT‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 4.5 vs 2.2 | 43 |

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 5.6 vs 4.2 | 71 |

| Lactitol† vs placebo | 4.9 vs 3.6 | 77 |

| Lactitol† vs lactulose | 5.5 vs 4.9 | 160 |

| Lactulose vs sorbitol† | 7.0 vs 6.7 | 330 |

| External abdominal kneading (before-after) | 3.9 vs 1.4 | 40 |

| * Agiolax is a combination bulk and stimulant laxative not readily found in the United States. | ||

| † Lactitol and sorbitol are sugar alcohols used as replacement sweeteners and approved by the FDA as food additives. | ||

| ‡ Number needed to treat (NNT) for 1 person to have 1 more stool per week. | ||

A subgroup analysis9 of 331 elderly patients enrolled in 2 RCTs of tegaserod found no difference in outcomes between treatment with tegaserod and placebo, although this analysis was limited by inadequate power.

Tegaserod linked to ischemic events. A recent analysis of clinical trials found a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular ischemic events associated with tegaserod. The manufacturer took the product off the market in compliance with an FDA request in March 2007.

Lubiprostone offers promise. Lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation, has been studied in 6 placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized Phase II and III clinical trials. In 2 unpublished pooled analyses of 3 of the trials, lubiprostone was found to be effective in a total of 220 elderly patients 65 years of age and older.10,11

Recommendations from others

The American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force evidence-based guidelines make no reference to age, but state that evidence is best for treatment with psyllium, tegaserod, polyethylene glycol, and lactulose.12 They found insufficient evidence to support use of stimulants, stool softeners, lubricants, herbal supplements, biofeedback, and alternative treatments.

The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on constipation are primarily based on expert opinion.13 Age is not specified in their recommendations. Dietary and exercise modifications are recommended as first-line treatments, followed by laxatives. Laxatives are recommended based on cost, in order from the least to most expensive agents. Suppositories, enemas, biofeedback, and (in refractory cases) surgery are recommended for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction.

The Registered Nurses Association of Ontario guidelines for constipation prevention in the older adult population recommend fluid and dietary fiber, regular exercise, and consistent toileting.14

1. Petticrew M, Watt I, Brand M. What’s the “best buy” for treatment of constipation? Results of a systematic review of the efficacy and comparative efficacy of laxatives in the elderly. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:387-393.

2. Petticrew M, Watt I, Sheldon T. Systematic review of the effectiveness of laxatives in the elderly. Health Technol Assess 1997;1:i–iv-1–52.

3. Kenny KA, Skelly JM. Dietary fiber for constipation in older adults: a systematic review. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2001;5:120-128.

4. Chin APMJ, van Poppel MN, van Mechelen W. Effects of resistance and functional-skills training on habitual activity and constipation among older adults living in long-term care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2006;6:9.-

5. Simmons SF, Schnelle JF. Effects of an exercise and scheduled-toileting intervention on appetite and constipation in nursing home residents. J Nutr Health Aging 2004;8:116-121.

6. Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld P, Talley NJ. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 suppl 1:S5-S21.

7. Mimidis K, Galinsky D, Rimon E, Papadopoulos V, Zicherman Y, Oreopoulos D. Use of a device that applies external kneading-like force on the abdomen for treatment of constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1971-1975.

8. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

9. Baun RF, Levy HB. Tegaserod for treating chronic constipation in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:309-313.

10. Ueno R, Joswick TR, Wahle A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly vs non-elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A189.-

11. Ueno R, Panas R, Wahle A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A188.-

12. American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 Suppl 1:S1-S4.

13. Locke GR, 3rd, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1761-1766.

14. Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO). Prevention of constipation in the older adult population. Toronto, Ontario: RNAO; 2005. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=7004&nbr=4213. Accessed on November 8, 2007.

There is no one best evidence-based treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly. While the most common first-line treatments are dietary fiber and exercise, the evidence is insufficient to support this approach in the geriatric population (strength of recommendation [SOR]: for dietary fiber: A, based on a systematic review; for exercise: SOR: B, based on 1 good- and 1 fair-quality randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Herbal supplements (such as aloe), alternative treatments (biofeedback), lubricants (mineral oil), and combination laxatives sold in the US have not been sufficiently studied in controlled trials to make a recommendation (SOR: A, based on systematic review).

An abdominal kneading device can be used to treat chronic constipation, but the evidence is limited (SOR: B, based on 1 cohort study.)

Polyethylene glycol has not been studied in the elderly. A newer agent, lubiprostone (Amitiza), appears to be effective for the treatment of chronic constipation for elderly patients (SOR: B, based on subgroup analysis of RCTs.)

Is the patient truly constipated?

Mandi Sehgal, MD

Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, University of Cincinnati

Many older people feel that if they do not have a bowel movement every day they are constipated. However, constipation is defined as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week. So, the first thing we must do is to confirm that the patient is truly constipated.

Before I start my patients on any medicine, I suggest a trial of increased daily water and fiber intake along with exercise, followed by a trial of stool softeners and stimulant laxatives, if needed. If all of these methods fail, I consider trying polyethylene glycol, which can be titrated to effect. As with all medication use by the elderly, it is important to titrate cautiously (“start low and go slow”) and add other medications only when necessary.

Evidence summary

Few well-designed studies have focused on constipation treatment among the elderly. Our search located 1 systematic review of pharmacologic management, a systematic review of fiber management, 2 RCTs on the effect of exercise, and 1 before-after cohort study on abdominal massage. These studies were all conducted among geriatric patients with constipation. Two high-quality systematic reviews regarding chronic constipation management for adults of all ages included management options not studied in exclusively geriatric populations, such as herbal supplements, biofeedback, tegaserod, and polyethylene glycol.

Laxatives, fiber, and exercise: Studies are inconclusive

Two good-quality systematic reviews looked at 10 RCTs comparing laxatives with placebo, and 10 RCTs comparing 1 laxative with another.1,2 The studies generally had few participants, were of short duration, and were conducted in institutional settings. Most lacked power to make valid conclusions. These studies varied in the reported outcome measures, including stool frequency, stool consistency, straining, decrease in laxative use, and symptom scores. The reviews concluded that the best pharmacologic treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly has not been established.

Five of the higher-quality studies attained statistical significance. They showed a small but significant improvement in bowel movement frequency with a laxative when compared with placebo or another laxative (TABLE). The authors noted that multiple poor-quality studies have shown nonsignificant trends for improved constipation symptoms with laxatives compared with placebo.

Inconsistent findings on fiber. A good-quality systematic review3 of dietary fiber in the treatment of constipation for older patients located 8 moderate- to high-quality studies (6 RCTs and 2 blinded before-after studies), with 269 study participants in institutional settings. Results among studies were inconsistent, casting doubt on the efficacy of fiber treatment for constipation in the institutionalized elder.

Two RCTs4,5 investigating the effect of exercise on 246 institutionalized older patients showed no improvement in constipation. One study was of good quality, reporting adequate power and used an intention-to-treat analysis. The other was of fair quality.

Alternative TXs not well studied

A high-quality systematic review6 of constipation management among adults of all ages in North America found a lack of quality RCTs examining herbal supplement treatment. Biofeedback has been studied in adult populations, but no RCTs with placebo or sham-controls have been published.

One before-after cohort study7 investigated an external kneading mechanical device (Free-Lax) that was applied to the abdomen for 20 minutes once daily in 30 randomly selected chronically constipated nursing home residents. Researchers found significant improvements in bowel movement frequency, stool consistency and volume, and colonic transit time without side effects (TABLE).

A look beyond geriatric patients

Polyethylene glycol, tegaserod, and lubiprostone have not been studied in trials of exclusively geriatric populations. Two high-quality systematic reviews,6,8 including medium- to high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic management of chronic constipation, found good evidence to support treatment with polyethylene glycol and tegaserod in adults of all ages. Of the 8 RCTs looking at polyethylene glycol, only 1 of the studies—a high-quality crossover comparison of polyethylene glycol vs placebo with 37 out-patient subjects—included a population with a mean age >60 years (mean age 62, range 42–89 years).

TABLE

How well do these interventions work for older patients with chronic constipation?

| INTERVENTION VS COMPARISON | STOOL FREQUENCY (STOOLS PER WEEK) | NNT‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 4.5 vs 2.2 | 43 |

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 5.6 vs 4.2 | 71 |

| Lactitol† vs placebo | 4.9 vs 3.6 | 77 |

| Lactitol† vs lactulose | 5.5 vs 4.9 | 160 |

| Lactulose vs sorbitol† | 7.0 vs 6.7 | 330 |

| External abdominal kneading (before-after) | 3.9 vs 1.4 | 40 |

| * Agiolax is a combination bulk and stimulant laxative not readily found in the United States. | ||

| † Lactitol and sorbitol are sugar alcohols used as replacement sweeteners and approved by the FDA as food additives. | ||

| ‡ Number needed to treat (NNT) for 1 person to have 1 more stool per week. | ||

A subgroup analysis9 of 331 elderly patients enrolled in 2 RCTs of tegaserod found no difference in outcomes between treatment with tegaserod and placebo, although this analysis was limited by inadequate power.

Tegaserod linked to ischemic events. A recent analysis of clinical trials found a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular ischemic events associated with tegaserod. The manufacturer took the product off the market in compliance with an FDA request in March 2007.

Lubiprostone offers promise. Lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation, has been studied in 6 placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized Phase II and III clinical trials. In 2 unpublished pooled analyses of 3 of the trials, lubiprostone was found to be effective in a total of 220 elderly patients 65 years of age and older.10,11

Recommendations from others

The American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force evidence-based guidelines make no reference to age, but state that evidence is best for treatment with psyllium, tegaserod, polyethylene glycol, and lactulose.12 They found insufficient evidence to support use of stimulants, stool softeners, lubricants, herbal supplements, biofeedback, and alternative treatments.

The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on constipation are primarily based on expert opinion.13 Age is not specified in their recommendations. Dietary and exercise modifications are recommended as first-line treatments, followed by laxatives. Laxatives are recommended based on cost, in order from the least to most expensive agents. Suppositories, enemas, biofeedback, and (in refractory cases) surgery are recommended for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction.

The Registered Nurses Association of Ontario guidelines for constipation prevention in the older adult population recommend fluid and dietary fiber, regular exercise, and consistent toileting.14

There is no one best evidence-based treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly. While the most common first-line treatments are dietary fiber and exercise, the evidence is insufficient to support this approach in the geriatric population (strength of recommendation [SOR]: for dietary fiber: A, based on a systematic review; for exercise: SOR: B, based on 1 good- and 1 fair-quality randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Herbal supplements (such as aloe), alternative treatments (biofeedback), lubricants (mineral oil), and combination laxatives sold in the US have not been sufficiently studied in controlled trials to make a recommendation (SOR: A, based on systematic review).

An abdominal kneading device can be used to treat chronic constipation, but the evidence is limited (SOR: B, based on 1 cohort study.)

Polyethylene glycol has not been studied in the elderly. A newer agent, lubiprostone (Amitiza), appears to be effective for the treatment of chronic constipation for elderly patients (SOR: B, based on subgroup analysis of RCTs.)

Is the patient truly constipated?

Mandi Sehgal, MD

Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, University of Cincinnati

Many older people feel that if they do not have a bowel movement every day they are constipated. However, constipation is defined as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week. So, the first thing we must do is to confirm that the patient is truly constipated.

Before I start my patients on any medicine, I suggest a trial of increased daily water and fiber intake along with exercise, followed by a trial of stool softeners and stimulant laxatives, if needed. If all of these methods fail, I consider trying polyethylene glycol, which can be titrated to effect. As with all medication use by the elderly, it is important to titrate cautiously (“start low and go slow”) and add other medications only when necessary.

Evidence summary

Few well-designed studies have focused on constipation treatment among the elderly. Our search located 1 systematic review of pharmacologic management, a systematic review of fiber management, 2 RCTs on the effect of exercise, and 1 before-after cohort study on abdominal massage. These studies were all conducted among geriatric patients with constipation. Two high-quality systematic reviews regarding chronic constipation management for adults of all ages included management options not studied in exclusively geriatric populations, such as herbal supplements, biofeedback, tegaserod, and polyethylene glycol.

Laxatives, fiber, and exercise: Studies are inconclusive

Two good-quality systematic reviews looked at 10 RCTs comparing laxatives with placebo, and 10 RCTs comparing 1 laxative with another.1,2 The studies generally had few participants, were of short duration, and were conducted in institutional settings. Most lacked power to make valid conclusions. These studies varied in the reported outcome measures, including stool frequency, stool consistency, straining, decrease in laxative use, and symptom scores. The reviews concluded that the best pharmacologic treatment for chronic constipation in the elderly has not been established.

Five of the higher-quality studies attained statistical significance. They showed a small but significant improvement in bowel movement frequency with a laxative when compared with placebo or another laxative (TABLE). The authors noted that multiple poor-quality studies have shown nonsignificant trends for improved constipation symptoms with laxatives compared with placebo.

Inconsistent findings on fiber. A good-quality systematic review3 of dietary fiber in the treatment of constipation for older patients located 8 moderate- to high-quality studies (6 RCTs and 2 blinded before-after studies), with 269 study participants in institutional settings. Results among studies were inconsistent, casting doubt on the efficacy of fiber treatment for constipation in the institutionalized elder.

Two RCTs4,5 investigating the effect of exercise on 246 institutionalized older patients showed no improvement in constipation. One study was of good quality, reporting adequate power and used an intention-to-treat analysis. The other was of fair quality.

Alternative TXs not well studied

A high-quality systematic review6 of constipation management among adults of all ages in North America found a lack of quality RCTs examining herbal supplement treatment. Biofeedback has been studied in adult populations, but no RCTs with placebo or sham-controls have been published.

One before-after cohort study7 investigated an external kneading mechanical device (Free-Lax) that was applied to the abdomen for 20 minutes once daily in 30 randomly selected chronically constipated nursing home residents. Researchers found significant improvements in bowel movement frequency, stool consistency and volume, and colonic transit time without side effects (TABLE).

A look beyond geriatric patients

Polyethylene glycol, tegaserod, and lubiprostone have not been studied in trials of exclusively geriatric populations. Two high-quality systematic reviews,6,8 including medium- to high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic management of chronic constipation, found good evidence to support treatment with polyethylene glycol and tegaserod in adults of all ages. Of the 8 RCTs looking at polyethylene glycol, only 1 of the studies—a high-quality crossover comparison of polyethylene glycol vs placebo with 37 out-patient subjects—included a population with a mean age >60 years (mean age 62, range 42–89 years).

TABLE

How well do these interventions work for older patients with chronic constipation?

| INTERVENTION VS COMPARISON | STOOL FREQUENCY (STOOLS PER WEEK) | NNT‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 4.5 vs 2.2 | 43 |

| Agiolax* vs lactulose | 5.6 vs 4.2 | 71 |

| Lactitol† vs placebo | 4.9 vs 3.6 | 77 |

| Lactitol† vs lactulose | 5.5 vs 4.9 | 160 |

| Lactulose vs sorbitol† | 7.0 vs 6.7 | 330 |

| External abdominal kneading (before-after) | 3.9 vs 1.4 | 40 |

| * Agiolax is a combination bulk and stimulant laxative not readily found in the United States. | ||

| † Lactitol and sorbitol are sugar alcohols used as replacement sweeteners and approved by the FDA as food additives. | ||

| ‡ Number needed to treat (NNT) for 1 person to have 1 more stool per week. | ||

A subgroup analysis9 of 331 elderly patients enrolled in 2 RCTs of tegaserod found no difference in outcomes between treatment with tegaserod and placebo, although this analysis was limited by inadequate power.

Tegaserod linked to ischemic events. A recent analysis of clinical trials found a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular ischemic events associated with tegaserod. The manufacturer took the product off the market in compliance with an FDA request in March 2007.

Lubiprostone offers promise. Lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation, has been studied in 6 placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized Phase II and III clinical trials. In 2 unpublished pooled analyses of 3 of the trials, lubiprostone was found to be effective in a total of 220 elderly patients 65 years of age and older.10,11

Recommendations from others

The American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force evidence-based guidelines make no reference to age, but state that evidence is best for treatment with psyllium, tegaserod, polyethylene glycol, and lactulose.12 They found insufficient evidence to support use of stimulants, stool softeners, lubricants, herbal supplements, biofeedback, and alternative treatments.

The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on constipation are primarily based on expert opinion.13 Age is not specified in their recommendations. Dietary and exercise modifications are recommended as first-line treatments, followed by laxatives. Laxatives are recommended based on cost, in order from the least to most expensive agents. Suppositories, enemas, biofeedback, and (in refractory cases) surgery are recommended for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction.

The Registered Nurses Association of Ontario guidelines for constipation prevention in the older adult population recommend fluid and dietary fiber, regular exercise, and consistent toileting.14

1. Petticrew M, Watt I, Brand M. What’s the “best buy” for treatment of constipation? Results of a systematic review of the efficacy and comparative efficacy of laxatives in the elderly. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:387-393.

2. Petticrew M, Watt I, Sheldon T. Systematic review of the effectiveness of laxatives in the elderly. Health Technol Assess 1997;1:i–iv-1–52.

3. Kenny KA, Skelly JM. Dietary fiber for constipation in older adults: a systematic review. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2001;5:120-128.

4. Chin APMJ, van Poppel MN, van Mechelen W. Effects of resistance and functional-skills training on habitual activity and constipation among older adults living in long-term care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2006;6:9.-

5. Simmons SF, Schnelle JF. Effects of an exercise and scheduled-toileting intervention on appetite and constipation in nursing home residents. J Nutr Health Aging 2004;8:116-121.

6. Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld P, Talley NJ. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 suppl 1:S5-S21.

7. Mimidis K, Galinsky D, Rimon E, Papadopoulos V, Zicherman Y, Oreopoulos D. Use of a device that applies external kneading-like force on the abdomen for treatment of constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1971-1975.

8. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

9. Baun RF, Levy HB. Tegaserod for treating chronic constipation in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:309-313.

10. Ueno R, Joswick TR, Wahle A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly vs non-elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A189.-

11. Ueno R, Panas R, Wahle A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A188.-

12. American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 Suppl 1:S1-S4.

13. Locke GR, 3rd, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1761-1766.

14. Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO). Prevention of constipation in the older adult population. Toronto, Ontario: RNAO; 2005. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=7004&nbr=4213. Accessed on November 8, 2007.

1. Petticrew M, Watt I, Brand M. What’s the “best buy” for treatment of constipation? Results of a systematic review of the efficacy and comparative efficacy of laxatives in the elderly. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:387-393.

2. Petticrew M, Watt I, Sheldon T. Systematic review of the effectiveness of laxatives in the elderly. Health Technol Assess 1997;1:i–iv-1–52.

3. Kenny KA, Skelly JM. Dietary fiber for constipation in older adults: a systematic review. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2001;5:120-128.

4. Chin APMJ, van Poppel MN, van Mechelen W. Effects of resistance and functional-skills training on habitual activity and constipation among older adults living in long-term care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2006;6:9.-

5. Simmons SF, Schnelle JF. Effects of an exercise and scheduled-toileting intervention on appetite and constipation in nursing home residents. J Nutr Health Aging 2004;8:116-121.

6. Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld P, Talley NJ. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 suppl 1:S5-S21.

7. Mimidis K, Galinsky D, Rimon E, Papadopoulos V, Zicherman Y, Oreopoulos D. Use of a device that applies external kneading-like force on the abdomen for treatment of constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1971-1975.

8. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

9. Baun RF, Levy HB. Tegaserod for treating chronic constipation in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:309-313.

10. Ueno R, Joswick TR, Wahle A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly vs non-elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A189.-

11. Ueno R, Panas R, Wahle A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of lubiprostone for the treatment of chronic constipation in elderly subjects. Gastroenterology 2006;130(suppl 2):A188.-

12. American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 Suppl 1:S1-S4.

13. Locke GR, 3rd, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1761-1766.

14. Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO). Prevention of constipation in the older adult population. Toronto, Ontario: RNAO; 2005. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=7004&nbr=4213. Accessed on November 8, 2007.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

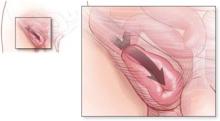

What is the risk of bowel strangulation in an adult with an untreated inguinal hernia?

The risk of bowel strangulation is estimated to be small—less than 1% per year (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on small cohort studies with short follow-up). Experts recommend repair for patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. These risk factors include advanced age, limited access to emergency care, significant concomitant illness, inability to recognize symptoms of bowel incarceration, and poor operative risk (American society of Anesthesiologists class III and IV) (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series). It is reasonable to offer elective surgery or watchful waiting to low-risk patients who understand the risks of strangulation (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series).

Watchful waiting, yes, but not for high-risk seniors

Michael K. Park, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Rose Family Medicine Residency, Denver

The evidence reinforces “watchful waiting” as a reasonable management approach. However, certain patients—say, a 66-year-old diabetic farmer—should probably undergo elective herniorrhaphy to preempt the increased risk of complications with emergent repair.

shared decision-making is an essential process in accounting for individual preferences. In addition to knowing the risks of strangulation, patients opting for surgery also need to be aware of the differences between open and laparoscopic techniques. The former may be done under local anesthesia; the latter decreases postoperative pain and recovery time, but requires general anesthesia and increases the rates of serious complications.

Evidence summary

In 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing elective repair of inguinal hernias with watchful waiting, the cohorts who made up the control groups experienced strangulation rates of 1.8 per thousand (0.18%) and 7.9 per thousand (0.79%) occurrences per patient-year.1,2 In the first of these 2 trials,1 with 364 control group patients, median follow-up was only 3.2 years (maximum 4.5 years), and by 4 years 31% of patients had crossed over to the treatment group for elective repair. The mean follow-up time in the second trial,2 which had 80 control group participants, was 1.6 years; 29% of patients eventually crossed over for repair.

Spanish study may have overestimated the risk. A retrospective study3 of 70 patients with incarcerated inguinal hernias presenting for emergency surgery in Northern Spain reported a cumulative 2.8% probability of strangulation at 3 months, rising to 4.5% after 2 years. This study did not include patients presenting for elective repair of hernias, and therefore it likely overestimated the rate of strangulation among patients in a primary care setting.

When to repair inguinal hernia

Experts recommend repair of an inguinal hernia in patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. Risk factors include advanced age and significant concomitant illness.

In 2001, a prospective study4 of 669 patients presenting for elective hernia repair in London found that only 0.3% of patients required resection of bowel or omentum.

Risk appears to be <1% a year. Collectively, these studies suggest that the risk of strangulation is less than 1% per year (0.18% to 0.79%) among all patients with inguinal hernias, at least in the first few years of the onset of the hernia. As you’d expect, the risk of strangulation is higher (2.8% to 4.5%) among patients presenting for emergency repair of incarcerated hernias. We found no prospective studies that followed patients for more than 4.5 years.

Age factors into poor outcomes

A number of studies5,6 have examined risk factors for increased rates of strangulation and poor outcomes. Older age increases the risk of a poor outcome, peaking in the seventh decade. Patient comorbidity and late hospitalization also make emergent repair more risky.3,5

Retrospective studies3,5,7 of the temporal duration and the natural history of inguinal hernias, as well as operative complication rates, have shown conflicting results.

70- and 80-year olds have greater risk. A Turkish study5 of patients needing emergent surgical repair found morbidity to be significantly related to American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, with mortality rates of 3% and 14% for ASA class III and IV patients, respectively. This was a retrospective chart review that analyzed factors responsible for unfavorable outcomes; it found increased complications in hernia patients who had coexisting disease, hernias of longer duration, as well as higher ASA class. This study5 and another retrospective study6 found the need for emergent repair peaked for patients 70 to 80 years of age.

longer history of herniation may more postop complications. The Spanish retrospective review3 of emergent surgical repair of incarcerated hernias (noted earlier) reported a 3.4% postoperative mortality rate. All deaths were among patients over 65 years of age and ASA class III or IV. This review also found more postoperative complications and a higher mortality for hernias present for more than 10 years.

Another study raises questions. A retrospective study from Israel8 also showed that patients who underwent emergency repair were older, had a longer history of herniation than those undergoing elective repair, and had higher ASA scores. However, a case-control study7 and a chart review9 found that the risk of strangulation was higher for hernias of shorter duration.

We found no studies addressing potential exacerbating conditions of inguinal hernia, such as chronic cough, bladder outlet obstruction with straining, constipation, obesity, or bilateral hernias.

Recommendations from others

All the textbooks and guidelines we identified acknowledge that many patients forego operation and remain minimally symptomatic for long periods of time, and that operations themselves have risks and complications.10–12 The avoidable risks of strangulation and emergent operation lead most experts to favor operative treatment.

In ACS Surgery: Principles & Practice 2007,10 the authors lament the difficulty of obtaining accurate studies of the natural history of inguinal hernia because surgeons have been taught that it is best to operate at diagnosis, making it hard to find an adequate population to study. The authors acknowledge that while many primary care physicians advise their patients to delay operations if the hernia is minimally asymptomatic, they do not share this belief.

The American College of Physicians’ PIER: The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource11 recommends assessing the hernia and the patient on a case-by-case basis. They recommend deferring an operation for poor-risk patients with minimal symptoms if the hernia is easily reducible and is unquestionably an inguinal hernia, if there are no past episodes of obstruction, and if the risks of untreated hernia are fully understood by the patient. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery makes virtually the same points and recommendations.12

1. Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006;295:285-292.

2. O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P. Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: A randomised clinical trial. Ann Surg 2006;244:167-173.

3. Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Solis JAS, Alvarez A, Alvarez JI. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: Presentation and outcome. Hernia 2004;8:121-126.

4. Hair A, Paterson C, Wright D, Baxter JN, O’Dwyer PJ. What effect does the duration of an inguinal hernia have on patient symptoms? J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:125-129.

5. Kulah B, Duzgun AP, Moran M, Kulacoglu IH, Ozmen MM, Coskun F. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Am J Surg 2001;182:455-459.

6. McEntee G, O’carroll A, Mooney B, Egan TJ, Delaney PV. Timing of strangulation in adult hernias. Br J Surg 1989;76:725-726.

7. Rai S, Chandra SS, Smile SR. A study of the risk of strangulation and obstruction in groin hernias. Aust N Z J Surg 1998;68:650-654.

8. Ohana manevwitch I, Weil R, et al. Inguinal hernia: challenging the traditional indication for surgery in asymptomatic patients. Hernia 2004;8:117-120.

9. Gallegos NC, Dawson J, Jarvis M, Hobsley M. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg 1991;78:1171-1173.

10. Fitzgibbons RJ, Richards AT, Quinn TH. Open hernia repair. In: Souba WW, Wilmore DW, Fink MP, et al, eds.ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice 2007.New York, NY: webMD Professional Publishing; 2007. Available at: www.acssurgery.com. Accessed on June 22, 2007.

11. Kingsnorth AN, Khan JA. Hernia. In: PIER—The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource [database online]. Philadelphia, Pa: American College of Physicians; 2007.

12. Malangoni MA, Gagliardi RJ. Hernias. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 17th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2004:1199–1217. Available at: www.mdconsult.com/das/book/0/view/1235/394.html. Accessed on November 8, 2007.

The risk of bowel strangulation is estimated to be small—less than 1% per year (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on small cohort studies with short follow-up). Experts recommend repair for patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. These risk factors include advanced age, limited access to emergency care, significant concomitant illness, inability to recognize symptoms of bowel incarceration, and poor operative risk (American society of Anesthesiologists class III and IV) (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series). It is reasonable to offer elective surgery or watchful waiting to low-risk patients who understand the risks of strangulation (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series).

Watchful waiting, yes, but not for high-risk seniors

Michael K. Park, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Rose Family Medicine Residency, Denver

The evidence reinforces “watchful waiting” as a reasonable management approach. However, certain patients—say, a 66-year-old diabetic farmer—should probably undergo elective herniorrhaphy to preempt the increased risk of complications with emergent repair.

shared decision-making is an essential process in accounting for individual preferences. In addition to knowing the risks of strangulation, patients opting for surgery also need to be aware of the differences between open and laparoscopic techniques. The former may be done under local anesthesia; the latter decreases postoperative pain and recovery time, but requires general anesthesia and increases the rates of serious complications.

Evidence summary

In 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing elective repair of inguinal hernias with watchful waiting, the cohorts who made up the control groups experienced strangulation rates of 1.8 per thousand (0.18%) and 7.9 per thousand (0.79%) occurrences per patient-year.1,2 In the first of these 2 trials,1 with 364 control group patients, median follow-up was only 3.2 years (maximum 4.5 years), and by 4 years 31% of patients had crossed over to the treatment group for elective repair. The mean follow-up time in the second trial,2 which had 80 control group participants, was 1.6 years; 29% of patients eventually crossed over for repair.

Spanish study may have overestimated the risk. A retrospective study3 of 70 patients with incarcerated inguinal hernias presenting for emergency surgery in Northern Spain reported a cumulative 2.8% probability of strangulation at 3 months, rising to 4.5% after 2 years. This study did not include patients presenting for elective repair of hernias, and therefore it likely overestimated the rate of strangulation among patients in a primary care setting.

When to repair inguinal hernia

Experts recommend repair of an inguinal hernia in patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. Risk factors include advanced age and significant concomitant illness.

In 2001, a prospective study4 of 669 patients presenting for elective hernia repair in London found that only 0.3% of patients required resection of bowel or omentum.

Risk appears to be <1% a year. Collectively, these studies suggest that the risk of strangulation is less than 1% per year (0.18% to 0.79%) among all patients with inguinal hernias, at least in the first few years of the onset of the hernia. As you’d expect, the risk of strangulation is higher (2.8% to 4.5%) among patients presenting for emergency repair of incarcerated hernias. We found no prospective studies that followed patients for more than 4.5 years.

Age factors into poor outcomes

A number of studies5,6 have examined risk factors for increased rates of strangulation and poor outcomes. Older age increases the risk of a poor outcome, peaking in the seventh decade. Patient comorbidity and late hospitalization also make emergent repair more risky.3,5

Retrospective studies3,5,7 of the temporal duration and the natural history of inguinal hernias, as well as operative complication rates, have shown conflicting results.

70- and 80-year olds have greater risk. A Turkish study5 of patients needing emergent surgical repair found morbidity to be significantly related to American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, with mortality rates of 3% and 14% for ASA class III and IV patients, respectively. This was a retrospective chart review that analyzed factors responsible for unfavorable outcomes; it found increased complications in hernia patients who had coexisting disease, hernias of longer duration, as well as higher ASA class. This study5 and another retrospective study6 found the need for emergent repair peaked for patients 70 to 80 years of age.

longer history of herniation may more postop complications. The Spanish retrospective review3 of emergent surgical repair of incarcerated hernias (noted earlier) reported a 3.4% postoperative mortality rate. All deaths were among patients over 65 years of age and ASA class III or IV. This review also found more postoperative complications and a higher mortality for hernias present for more than 10 years.

Another study raises questions. A retrospective study from Israel8 also showed that patients who underwent emergency repair were older, had a longer history of herniation than those undergoing elective repair, and had higher ASA scores. However, a case-control study7 and a chart review9 found that the risk of strangulation was higher for hernias of shorter duration.

We found no studies addressing potential exacerbating conditions of inguinal hernia, such as chronic cough, bladder outlet obstruction with straining, constipation, obesity, or bilateral hernias.

Recommendations from others

All the textbooks and guidelines we identified acknowledge that many patients forego operation and remain minimally symptomatic for long periods of time, and that operations themselves have risks and complications.10–12 The avoidable risks of strangulation and emergent operation lead most experts to favor operative treatment.

In ACS Surgery: Principles & Practice 2007,10 the authors lament the difficulty of obtaining accurate studies of the natural history of inguinal hernia because surgeons have been taught that it is best to operate at diagnosis, making it hard to find an adequate population to study. The authors acknowledge that while many primary care physicians advise their patients to delay operations if the hernia is minimally asymptomatic, they do not share this belief.

The American College of Physicians’ PIER: The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource11 recommends assessing the hernia and the patient on a case-by-case basis. They recommend deferring an operation for poor-risk patients with minimal symptoms if the hernia is easily reducible and is unquestionably an inguinal hernia, if there are no past episodes of obstruction, and if the risks of untreated hernia are fully understood by the patient. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery makes virtually the same points and recommendations.12

The risk of bowel strangulation is estimated to be small—less than 1% per year (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on small cohort studies with short follow-up). Experts recommend repair for patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. These risk factors include advanced age, limited access to emergency care, significant concomitant illness, inability to recognize symptoms of bowel incarceration, and poor operative risk (American society of Anesthesiologists class III and IV) (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series). It is reasonable to offer elective surgery or watchful waiting to low-risk patients who understand the risks of strangulation (SOR: C, based on expert opinion and case series).

Watchful waiting, yes, but not for high-risk seniors

Michael K. Park, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Rose Family Medicine Residency, Denver

The evidence reinforces “watchful waiting” as a reasonable management approach. However, certain patients—say, a 66-year-old diabetic farmer—should probably undergo elective herniorrhaphy to preempt the increased risk of complications with emergent repair.

shared decision-making is an essential process in accounting for individual preferences. In addition to knowing the risks of strangulation, patients opting for surgery also need to be aware of the differences between open and laparoscopic techniques. The former may be done under local anesthesia; the latter decreases postoperative pain and recovery time, but requires general anesthesia and increases the rates of serious complications.

Evidence summary

In 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing elective repair of inguinal hernias with watchful waiting, the cohorts who made up the control groups experienced strangulation rates of 1.8 per thousand (0.18%) and 7.9 per thousand (0.79%) occurrences per patient-year.1,2 In the first of these 2 trials,1 with 364 control group patients, median follow-up was only 3.2 years (maximum 4.5 years), and by 4 years 31% of patients had crossed over to the treatment group for elective repair. The mean follow-up time in the second trial,2 which had 80 control group participants, was 1.6 years; 29% of patients eventually crossed over for repair.

Spanish study may have overestimated the risk. A retrospective study3 of 70 patients with incarcerated inguinal hernias presenting for emergency surgery in Northern Spain reported a cumulative 2.8% probability of strangulation at 3 months, rising to 4.5% after 2 years. This study did not include patients presenting for elective repair of hernias, and therefore it likely overestimated the rate of strangulation among patients in a primary care setting.

When to repair inguinal hernia

Experts recommend repair of an inguinal hernia in patients with risk factors for poor outcomes after potential strangulation. Risk factors include advanced age and significant concomitant illness.

In 2001, a prospective study4 of 669 patients presenting for elective hernia repair in London found that only 0.3% of patients required resection of bowel or omentum.

Risk appears to be <1% a year. Collectively, these studies suggest that the risk of strangulation is less than 1% per year (0.18% to 0.79%) among all patients with inguinal hernias, at least in the first few years of the onset of the hernia. As you’d expect, the risk of strangulation is higher (2.8% to 4.5%) among patients presenting for emergency repair of incarcerated hernias. We found no prospective studies that followed patients for more than 4.5 years.

Age factors into poor outcomes

A number of studies5,6 have examined risk factors for increased rates of strangulation and poor outcomes. Older age increases the risk of a poor outcome, peaking in the seventh decade. Patient comorbidity and late hospitalization also make emergent repair more risky.3,5

Retrospective studies3,5,7 of the temporal duration and the natural history of inguinal hernias, as well as operative complication rates, have shown conflicting results.

70- and 80-year olds have greater risk. A Turkish study5 of patients needing emergent surgical repair found morbidity to be significantly related to American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, with mortality rates of 3% and 14% for ASA class III and IV patients, respectively. This was a retrospective chart review that analyzed factors responsible for unfavorable outcomes; it found increased complications in hernia patients who had coexisting disease, hernias of longer duration, as well as higher ASA class. This study5 and another retrospective study6 found the need for emergent repair peaked for patients 70 to 80 years of age.

longer history of herniation may more postop complications. The Spanish retrospective review3 of emergent surgical repair of incarcerated hernias (noted earlier) reported a 3.4% postoperative mortality rate. All deaths were among patients over 65 years of age and ASA class III or IV. This review also found more postoperative complications and a higher mortality for hernias present for more than 10 years.

Another study raises questions. A retrospective study from Israel8 also showed that patients who underwent emergency repair were older, had a longer history of herniation than those undergoing elective repair, and had higher ASA scores. However, a case-control study7 and a chart review9 found that the risk of strangulation was higher for hernias of shorter duration.

We found no studies addressing potential exacerbating conditions of inguinal hernia, such as chronic cough, bladder outlet obstruction with straining, constipation, obesity, or bilateral hernias.

Recommendations from others

All the textbooks and guidelines we identified acknowledge that many patients forego operation and remain minimally symptomatic for long periods of time, and that operations themselves have risks and complications.10–12 The avoidable risks of strangulation and emergent operation lead most experts to favor operative treatment.

In ACS Surgery: Principles & Practice 2007,10 the authors lament the difficulty of obtaining accurate studies of the natural history of inguinal hernia because surgeons have been taught that it is best to operate at diagnosis, making it hard to find an adequate population to study. The authors acknowledge that while many primary care physicians advise their patients to delay operations if the hernia is minimally asymptomatic, they do not share this belief.

The American College of Physicians’ PIER: The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource11 recommends assessing the hernia and the patient on a case-by-case basis. They recommend deferring an operation for poor-risk patients with minimal symptoms if the hernia is easily reducible and is unquestionably an inguinal hernia, if there are no past episodes of obstruction, and if the risks of untreated hernia are fully understood by the patient. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery makes virtually the same points and recommendations.12

1. Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006;295:285-292.

2. O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P. Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: A randomised clinical trial. Ann Surg 2006;244:167-173.

3. Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Solis JAS, Alvarez A, Alvarez JI. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: Presentation and outcome. Hernia 2004;8:121-126.

4. Hair A, Paterson C, Wright D, Baxter JN, O’Dwyer PJ. What effect does the duration of an inguinal hernia have on patient symptoms? J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:125-129.

5. Kulah B, Duzgun AP, Moran M, Kulacoglu IH, Ozmen MM, Coskun F. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Am J Surg 2001;182:455-459.

6. McEntee G, O’carroll A, Mooney B, Egan TJ, Delaney PV. Timing of strangulation in adult hernias. Br J Surg 1989;76:725-726.

7. Rai S, Chandra SS, Smile SR. A study of the risk of strangulation and obstruction in groin hernias. Aust N Z J Surg 1998;68:650-654.

8. Ohana manevwitch I, Weil R, et al. Inguinal hernia: challenging the traditional indication for surgery in asymptomatic patients. Hernia 2004;8:117-120.

9. Gallegos NC, Dawson J, Jarvis M, Hobsley M. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg 1991;78:1171-1173.

10. Fitzgibbons RJ, Richards AT, Quinn TH. Open hernia repair. In: Souba WW, Wilmore DW, Fink MP, et al, eds.ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice 2007.New York, NY: webMD Professional Publishing; 2007. Available at: www.acssurgery.com. Accessed on June 22, 2007.

11. Kingsnorth AN, Khan JA. Hernia. In: PIER—The Physicians’ Information and Education Resource [database online]. Philadelphia, Pa: American College of Physicians; 2007.

12. Malangoni MA, Gagliardi RJ. Hernias. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 17th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2004:1199–1217. Available at: www.mdconsult.com/das/book/0/view/1235/394.html. Accessed on November 8, 2007.

1. Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006;295:285-292.

2. O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P. Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: A randomised clinical trial. Ann Surg 2006;244:167-173.

3. Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Solis JAS, Alvarez A, Alvarez JI. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: Presentation and outcome. Hernia 2004;8:121-126.

4. Hair A, Paterson C, Wright D, Baxter JN, O’Dwyer PJ. What effect does the duration of an inguinal hernia have on patient symptoms? J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:125-129.

5. Kulah B, Duzgun AP, Moran M, Kulacoglu IH, Ozmen MM, Coskun F. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Am J Surg 2001;182:455-459.