User login

Implementation of a Virtual Huddle to Support Patient Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged hospital medicine teams to care for patients with complex respiratory needs, comply with evolving protocols, and remain abreast of new therapies.1,2 Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) faculty grappled with similar issues, acknowledging that their critical care expertise could be beneficial outside of the intensive care unit (ICU). Clinical pharmacists managed the procurement, allocation, and monitoring of complex (and sometimes limited) pharmacologic therapies. Although strategies used by health care systems to prepare and restructure for COVID-19 are reported, processes to enhance multidisciplinary care are limited.3,4 Therefore, we developed the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program using video conference to support hospital medicine teams caring for patients with COVID-19 and high disease severity.

Program Description

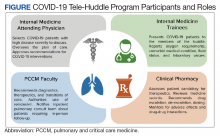

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, is a 349-bed, level 1A federal health care facility serving more than 113,000 veterans in southeast Texas.5 The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program took place over a 4-week period from July 6 to August 2, 2020. By the end of the 4-week period, there was a decline in the number of COVID patient admissions and thus the need for the huddle. Participation in the huddle also declined, likely reflecting the end of the surge and an increase in knowledge about COVID management acquired by the teams. Each COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation session consisted of at least 1 member from each hospital medicine team, 1 to 2 PCCM faculty members, and 1 to 2 clinical pharmacy specialists (Figure). The consultation team members included 4 PCCM faculty members and 2 clinical pharmacy specialists. The internal medicine (IM) participants included 10 ward teams with a total of 20 interns (PGY1), 12 upper-level residents (PGY2 and PGY 3), and 10 attending physicians.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program was a daily (including weekends) video conference. The hospital medicine team members joined the huddle from team workrooms, using webcams supplied by the MEDVAMC information technology department. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation team members joined remotely. Each hospital medicine team joined the huddle at a pre-assigned 15- to 30-minute time allotment, which varied based on patient volume. Participation in the huddle was mandatory for the first week and became optional thereafter. This was in recognition of the steep learning curve and provided the teams both basic knowledge of COVID management and a shared understanding of when a multidisciplinary consultation would be critical. Mandatory daily participation was challenging due to the pressures of patient volume during the surge.

COVID-19 patients with high disease severity were discussed during huddles based on specific criteria: all newly admitted COVID-19 patients, patients requiring step-down level of care, those with increasing oxygen requirements, and/or patients requiring authorization of remdesivir therapy, which required clinical pharmacy authorization at MEDVAMC. The hospital medicine teams reported the patients’ oxygen requirements, comorbid medical conditions, current and prior therapies, fluid status, and relevant laboratory values. A dashboard using the Premier Inc. TheraDoc clinical decision support system was developed to display patient vital signs, laboratory values, and medications. The PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists listened to inpatient medicine teams presentations and used the dashboard and radiographic images to formulate clinical decisions. Discussion of a patient at the huddle did not preclude in-person consultation at any time.

Tele-Huddles were not recorded, and all protected health information discussed was accessed through the electronic health record using a secure network. Data on length of the meeting, number of patients discussed, and management decisions were recorded daily in a spreadsheet. At the end of the 4-week surge, participants in the program completed a survey, which assessed participant demographics, prior experience with COVID-19, and satisfaction with the program based on a series of agree/disagree questions.

Program Metrics

During the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program 4-week evaluation period, 323 encounters were discussed with 117 unique patients with COVID-19. A median (IQR) of 5 (4-8) hospital medicine teams discussed 15 (9-18) patients. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program lasted a median (IQR) 74 (53-94) minutes. A mean (SD) 27% (13) of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the acute care services were discussed.

The multidisciplinary team provided 247 chest X-ray interpretations, 82 diagnostic recommendations, 206 therapeutic recommendations, and 32 transition of care recommendations (Table 1). A total of 55 (47%) patients were given remdesivir with first dose authorized by clinical pharmacy and given within a median (IQR) 6 (3-10) hours after the order was placed. Oxygen therapy, including titration and de-escalation of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), was used for 26 (22.2%) patients. Additional interventions included the review of imaging, the assessment of volume status to guide diuretic recommendations, and the discussion of goals of care.

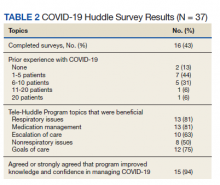

Of the participating IM trainees and attendings, 16 of 37 (43%) completed the user survey (Table 2). Prior experience with COVID-19 patients varied, with 7 of 16 respondents indicating experience with ≥ 5 patients with COVID-19 prior to the intervention period. Respondents believed that the huddle was helpful in management of respiratory issues (13 of 16), management of medications (13 of 16), escalation of care to ICU (10 of 16), and management of nonrespiratory issues (8 of 16) and goals of care (12 of 16). Fifteen of 16 participants strongly agreed or agreed that the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program improved their knowledge and confidence in managing patients. One participant commented, “Getting interdisciplinary help on COVID patients has really helped our team feel confident in our decisions about some of these very complex patients.” Another respondent commented, “Reliability was very helpful for planning how to discuss updates with our patients rather than the formal consultative process.”

Discussion

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems have been challenged to manage a large volume of patients, often with high disease severity, in non-ICU settings. This surge in cases has placed strain on hospital medicine teams. There is a subset of patients with COVID-19 with high disease severity that may be managed safely by hospital medicine teams, provided the accessibility and support of consultants, such as PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists.

Huddles are defined as functional groups of people focused on enhancing communication and care coordination to benefit patient safety. While often brief in nature, huddles can encompass a variety of structures, agendas, and outcome measures.6,7 We implemented a modified huddle using video conferencing to provide important aspects of critical care for patients with COVID-19. Face-to-face evaluation of about 15 patients each day would have strained an already burdened PCCM faculty who were providing additional critical care services as part of the surge response. Conversion of in-person consultations to the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for mitigation of COVID-19 transmission risk for additional clinicians, conservation of personal protective equipment, and more effective communication between acute inpatient practitioners and clinical services. The huddle model expedited the authorization and delivery of therapeutics, including remdesivir, which was prescribed for many patients discussed. Clinical pharmacists provided a review of all medications with input on escalation, de-escalation, dosing, drug-drug interactions, and emergency use authorization therapies.

Our experience resonates with previously described advantages of a huddle model, including the reliability of the consultation, empowerment for all members with a de-emphasis on hierarchy and accountability expected by all.8 The huddle provided situational awareness about patients that may require escalation of care to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Assistance with these transitions of care was highly appreciated by the hospital medicine teams who voiced that these decisions were quite challenging. COVID-19 patients at risk for decompensation were referred for in-person consultation and follow-up if required.

addition, the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for a safe and dependable venue for IM trainees and attending physicians to voice questions and concerns about their patients. We observed the development of a shared mental model among all huddle participants, in the face of a steep learning curve on the management of patients with complex respiratory needs. This was reflected in the survey: Most respondents reported improved knowledge and confidence in managing these patients. Situational awareness that arose from the huddle provided the PCCM faculty the opportunity to guide the inpatient ward teams on next steps whether it be escalation to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Facilitation of transitions of care were voiced as challenging decisions faced by the inpatient ward teams, and there was appreciation for additional support from the PCCM faculty in making these difficult decisions.

Challenges and Opportunities

This was a single-center experience caring for veterans. Challenges with having virtual huddles during the COVID-19 surge involved both time for the health care practitioners and technology. This was recognized early by the educational leaders at our facility, and headsets and cameras were purchased for the team rooms and made available as quickly as possible. Another limitation was the unpredictability and variability of patient volume for specific teams that sometimes would affect the efficiency of the huddle. The number of teams who attended the COVID-19 huddle was highest for the first 2 weeks (maximum of 9 teams) but declined to a nadir of 3 at the end of the month. This reflected the increase in knowledge about COVID-19 and respiratory disease that the teams acquired initially as well as a decline in COVID-19 patient admissions over those weeks.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program model also can be expanded to include other frontline clinicians, including nurses and respiratory therapists. For example, case management huddles were performed in a similar way during the COVID-19 surge to allow for efficient and effective multidisciplinary conversations about patients

Conclusions

Given the rise of telemedicine and availability of video conferencing services, virtual huddles can be implemented in institutions with appropriate staff and remote access to health records. Multidisciplinary consultation services using video conferencing can serve as an adjunct to the traditional, in-person consultation service model for patients with complex needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all of the Baylor Internal Medicine house staff and internal medicine attendings who participated in our huddle and more importantly, cared for our veterans during this COVID-19 surge.

1. Heymann DL, Shindo N; WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: what is next for public health?. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):542-545. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

2. Dichter JR, Kanter RK, Dries D, et al; Task Force for Mass Critical Care. System-level planning, coordination, and communication: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(suppl 4):e87S-e102S. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0738

3. Chowdhury JM, Patel M, Zheng M, Abramian O, Criner GJ. Mobilization and preparation of a large urban academic center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(8):922-925. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-259PS

4. Uppal A, Silvestri DM, Siegler M, et al. Critical care and emergency department response at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1443-1449. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00901

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center- Houston, Texas. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/about

6. Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, McDaniel RR Jr, Pugh J. Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):2-12. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009

7. Franklin BJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team huddles on patient safety: a systematic review and proposed taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(10):1-2. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009911

8. Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM, Muething SE. Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):899-906. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged hospital medicine teams to care for patients with complex respiratory needs, comply with evolving protocols, and remain abreast of new therapies.1,2 Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) faculty grappled with similar issues, acknowledging that their critical care expertise could be beneficial outside of the intensive care unit (ICU). Clinical pharmacists managed the procurement, allocation, and monitoring of complex (and sometimes limited) pharmacologic therapies. Although strategies used by health care systems to prepare and restructure for COVID-19 are reported, processes to enhance multidisciplinary care are limited.3,4 Therefore, we developed the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program using video conference to support hospital medicine teams caring for patients with COVID-19 and high disease severity.

Program Description

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, is a 349-bed, level 1A federal health care facility serving more than 113,000 veterans in southeast Texas.5 The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program took place over a 4-week period from July 6 to August 2, 2020. By the end of the 4-week period, there was a decline in the number of COVID patient admissions and thus the need for the huddle. Participation in the huddle also declined, likely reflecting the end of the surge and an increase in knowledge about COVID management acquired by the teams. Each COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation session consisted of at least 1 member from each hospital medicine team, 1 to 2 PCCM faculty members, and 1 to 2 clinical pharmacy specialists (Figure). The consultation team members included 4 PCCM faculty members and 2 clinical pharmacy specialists. The internal medicine (IM) participants included 10 ward teams with a total of 20 interns (PGY1), 12 upper-level residents (PGY2 and PGY 3), and 10 attending physicians.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program was a daily (including weekends) video conference. The hospital medicine team members joined the huddle from team workrooms, using webcams supplied by the MEDVAMC information technology department. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation team members joined remotely. Each hospital medicine team joined the huddle at a pre-assigned 15- to 30-minute time allotment, which varied based on patient volume. Participation in the huddle was mandatory for the first week and became optional thereafter. This was in recognition of the steep learning curve and provided the teams both basic knowledge of COVID management and a shared understanding of when a multidisciplinary consultation would be critical. Mandatory daily participation was challenging due to the pressures of patient volume during the surge.

COVID-19 patients with high disease severity were discussed during huddles based on specific criteria: all newly admitted COVID-19 patients, patients requiring step-down level of care, those with increasing oxygen requirements, and/or patients requiring authorization of remdesivir therapy, which required clinical pharmacy authorization at MEDVAMC. The hospital medicine teams reported the patients’ oxygen requirements, comorbid medical conditions, current and prior therapies, fluid status, and relevant laboratory values. A dashboard using the Premier Inc. TheraDoc clinical decision support system was developed to display patient vital signs, laboratory values, and medications. The PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists listened to inpatient medicine teams presentations and used the dashboard and radiographic images to formulate clinical decisions. Discussion of a patient at the huddle did not preclude in-person consultation at any time.

Tele-Huddles were not recorded, and all protected health information discussed was accessed through the electronic health record using a secure network. Data on length of the meeting, number of patients discussed, and management decisions were recorded daily in a spreadsheet. At the end of the 4-week surge, participants in the program completed a survey, which assessed participant demographics, prior experience with COVID-19, and satisfaction with the program based on a series of agree/disagree questions.

Program Metrics

During the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program 4-week evaluation period, 323 encounters were discussed with 117 unique patients with COVID-19. A median (IQR) of 5 (4-8) hospital medicine teams discussed 15 (9-18) patients. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program lasted a median (IQR) 74 (53-94) minutes. A mean (SD) 27% (13) of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the acute care services were discussed.

The multidisciplinary team provided 247 chest X-ray interpretations, 82 diagnostic recommendations, 206 therapeutic recommendations, and 32 transition of care recommendations (Table 1). A total of 55 (47%) patients were given remdesivir with first dose authorized by clinical pharmacy and given within a median (IQR) 6 (3-10) hours after the order was placed. Oxygen therapy, including titration and de-escalation of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), was used for 26 (22.2%) patients. Additional interventions included the review of imaging, the assessment of volume status to guide diuretic recommendations, and the discussion of goals of care.

Of the participating IM trainees and attendings, 16 of 37 (43%) completed the user survey (Table 2). Prior experience with COVID-19 patients varied, with 7 of 16 respondents indicating experience with ≥ 5 patients with COVID-19 prior to the intervention period. Respondents believed that the huddle was helpful in management of respiratory issues (13 of 16), management of medications (13 of 16), escalation of care to ICU (10 of 16), and management of nonrespiratory issues (8 of 16) and goals of care (12 of 16). Fifteen of 16 participants strongly agreed or agreed that the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program improved their knowledge and confidence in managing patients. One participant commented, “Getting interdisciplinary help on COVID patients has really helped our team feel confident in our decisions about some of these very complex patients.” Another respondent commented, “Reliability was very helpful for planning how to discuss updates with our patients rather than the formal consultative process.”

Discussion

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems have been challenged to manage a large volume of patients, often with high disease severity, in non-ICU settings. This surge in cases has placed strain on hospital medicine teams. There is a subset of patients with COVID-19 with high disease severity that may be managed safely by hospital medicine teams, provided the accessibility and support of consultants, such as PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists.

Huddles are defined as functional groups of people focused on enhancing communication and care coordination to benefit patient safety. While often brief in nature, huddles can encompass a variety of structures, agendas, and outcome measures.6,7 We implemented a modified huddle using video conferencing to provide important aspects of critical care for patients with COVID-19. Face-to-face evaluation of about 15 patients each day would have strained an already burdened PCCM faculty who were providing additional critical care services as part of the surge response. Conversion of in-person consultations to the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for mitigation of COVID-19 transmission risk for additional clinicians, conservation of personal protective equipment, and more effective communication between acute inpatient practitioners and clinical services. The huddle model expedited the authorization and delivery of therapeutics, including remdesivir, which was prescribed for many patients discussed. Clinical pharmacists provided a review of all medications with input on escalation, de-escalation, dosing, drug-drug interactions, and emergency use authorization therapies.

Our experience resonates with previously described advantages of a huddle model, including the reliability of the consultation, empowerment for all members with a de-emphasis on hierarchy and accountability expected by all.8 The huddle provided situational awareness about patients that may require escalation of care to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Assistance with these transitions of care was highly appreciated by the hospital medicine teams who voiced that these decisions were quite challenging. COVID-19 patients at risk for decompensation were referred for in-person consultation and follow-up if required.

addition, the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for a safe and dependable venue for IM trainees and attending physicians to voice questions and concerns about their patients. We observed the development of a shared mental model among all huddle participants, in the face of a steep learning curve on the management of patients with complex respiratory needs. This was reflected in the survey: Most respondents reported improved knowledge and confidence in managing these patients. Situational awareness that arose from the huddle provided the PCCM faculty the opportunity to guide the inpatient ward teams on next steps whether it be escalation to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Facilitation of transitions of care were voiced as challenging decisions faced by the inpatient ward teams, and there was appreciation for additional support from the PCCM faculty in making these difficult decisions.

Challenges and Opportunities

This was a single-center experience caring for veterans. Challenges with having virtual huddles during the COVID-19 surge involved both time for the health care practitioners and technology. This was recognized early by the educational leaders at our facility, and headsets and cameras were purchased for the team rooms and made available as quickly as possible. Another limitation was the unpredictability and variability of patient volume for specific teams that sometimes would affect the efficiency of the huddle. The number of teams who attended the COVID-19 huddle was highest for the first 2 weeks (maximum of 9 teams) but declined to a nadir of 3 at the end of the month. This reflected the increase in knowledge about COVID-19 and respiratory disease that the teams acquired initially as well as a decline in COVID-19 patient admissions over those weeks.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program model also can be expanded to include other frontline clinicians, including nurses and respiratory therapists. For example, case management huddles were performed in a similar way during the COVID-19 surge to allow for efficient and effective multidisciplinary conversations about patients

Conclusions

Given the rise of telemedicine and availability of video conferencing services, virtual huddles can be implemented in institutions with appropriate staff and remote access to health records. Multidisciplinary consultation services using video conferencing can serve as an adjunct to the traditional, in-person consultation service model for patients with complex needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all of the Baylor Internal Medicine house staff and internal medicine attendings who participated in our huddle and more importantly, cared for our veterans during this COVID-19 surge.

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged hospital medicine teams to care for patients with complex respiratory needs, comply with evolving protocols, and remain abreast of new therapies.1,2 Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) faculty grappled with similar issues, acknowledging that their critical care expertise could be beneficial outside of the intensive care unit (ICU). Clinical pharmacists managed the procurement, allocation, and monitoring of complex (and sometimes limited) pharmacologic therapies. Although strategies used by health care systems to prepare and restructure for COVID-19 are reported, processes to enhance multidisciplinary care are limited.3,4 Therefore, we developed the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program using video conference to support hospital medicine teams caring for patients with COVID-19 and high disease severity.

Program Description

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, is a 349-bed, level 1A federal health care facility serving more than 113,000 veterans in southeast Texas.5 The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program took place over a 4-week period from July 6 to August 2, 2020. By the end of the 4-week period, there was a decline in the number of COVID patient admissions and thus the need for the huddle. Participation in the huddle also declined, likely reflecting the end of the surge and an increase in knowledge about COVID management acquired by the teams. Each COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation session consisted of at least 1 member from each hospital medicine team, 1 to 2 PCCM faculty members, and 1 to 2 clinical pharmacy specialists (Figure). The consultation team members included 4 PCCM faculty members and 2 clinical pharmacy specialists. The internal medicine (IM) participants included 10 ward teams with a total of 20 interns (PGY1), 12 upper-level residents (PGY2 and PGY 3), and 10 attending physicians.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program was a daily (including weekends) video conference. The hospital medicine team members joined the huddle from team workrooms, using webcams supplied by the MEDVAMC information technology department. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation team members joined remotely. Each hospital medicine team joined the huddle at a pre-assigned 15- to 30-minute time allotment, which varied based on patient volume. Participation in the huddle was mandatory for the first week and became optional thereafter. This was in recognition of the steep learning curve and provided the teams both basic knowledge of COVID management and a shared understanding of when a multidisciplinary consultation would be critical. Mandatory daily participation was challenging due to the pressures of patient volume during the surge.

COVID-19 patients with high disease severity were discussed during huddles based on specific criteria: all newly admitted COVID-19 patients, patients requiring step-down level of care, those with increasing oxygen requirements, and/or patients requiring authorization of remdesivir therapy, which required clinical pharmacy authorization at MEDVAMC. The hospital medicine teams reported the patients’ oxygen requirements, comorbid medical conditions, current and prior therapies, fluid status, and relevant laboratory values. A dashboard using the Premier Inc. TheraDoc clinical decision support system was developed to display patient vital signs, laboratory values, and medications. The PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists listened to inpatient medicine teams presentations and used the dashboard and radiographic images to formulate clinical decisions. Discussion of a patient at the huddle did not preclude in-person consultation at any time.

Tele-Huddles were not recorded, and all protected health information discussed was accessed through the electronic health record using a secure network. Data on length of the meeting, number of patients discussed, and management decisions were recorded daily in a spreadsheet. At the end of the 4-week surge, participants in the program completed a survey, which assessed participant demographics, prior experience with COVID-19, and satisfaction with the program based on a series of agree/disagree questions.

Program Metrics

During the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program 4-week evaluation period, 323 encounters were discussed with 117 unique patients with COVID-19. A median (IQR) of 5 (4-8) hospital medicine teams discussed 15 (9-18) patients. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program lasted a median (IQR) 74 (53-94) minutes. A mean (SD) 27% (13) of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the acute care services were discussed.

The multidisciplinary team provided 247 chest X-ray interpretations, 82 diagnostic recommendations, 206 therapeutic recommendations, and 32 transition of care recommendations (Table 1). A total of 55 (47%) patients were given remdesivir with first dose authorized by clinical pharmacy and given within a median (IQR) 6 (3-10) hours after the order was placed. Oxygen therapy, including titration and de-escalation of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), was used for 26 (22.2%) patients. Additional interventions included the review of imaging, the assessment of volume status to guide diuretic recommendations, and the discussion of goals of care.

Of the participating IM trainees and attendings, 16 of 37 (43%) completed the user survey (Table 2). Prior experience with COVID-19 patients varied, with 7 of 16 respondents indicating experience with ≥ 5 patients with COVID-19 prior to the intervention period. Respondents believed that the huddle was helpful in management of respiratory issues (13 of 16), management of medications (13 of 16), escalation of care to ICU (10 of 16), and management of nonrespiratory issues (8 of 16) and goals of care (12 of 16). Fifteen of 16 participants strongly agreed or agreed that the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program improved their knowledge and confidence in managing patients. One participant commented, “Getting interdisciplinary help on COVID patients has really helped our team feel confident in our decisions about some of these very complex patients.” Another respondent commented, “Reliability was very helpful for planning how to discuss updates with our patients rather than the formal consultative process.”

Discussion

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems have been challenged to manage a large volume of patients, often with high disease severity, in non-ICU settings. This surge in cases has placed strain on hospital medicine teams. There is a subset of patients with COVID-19 with high disease severity that may be managed safely by hospital medicine teams, provided the accessibility and support of consultants, such as PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists.

Huddles are defined as functional groups of people focused on enhancing communication and care coordination to benefit patient safety. While often brief in nature, huddles can encompass a variety of structures, agendas, and outcome measures.6,7 We implemented a modified huddle using video conferencing to provide important aspects of critical care for patients with COVID-19. Face-to-face evaluation of about 15 patients each day would have strained an already burdened PCCM faculty who were providing additional critical care services as part of the surge response. Conversion of in-person consultations to the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for mitigation of COVID-19 transmission risk for additional clinicians, conservation of personal protective equipment, and more effective communication between acute inpatient practitioners and clinical services. The huddle model expedited the authorization and delivery of therapeutics, including remdesivir, which was prescribed for many patients discussed. Clinical pharmacists provided a review of all medications with input on escalation, de-escalation, dosing, drug-drug interactions, and emergency use authorization therapies.

Our experience resonates with previously described advantages of a huddle model, including the reliability of the consultation, empowerment for all members with a de-emphasis on hierarchy and accountability expected by all.8 The huddle provided situational awareness about patients that may require escalation of care to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Assistance with these transitions of care was highly appreciated by the hospital medicine teams who voiced that these decisions were quite challenging. COVID-19 patients at risk for decompensation were referred for in-person consultation and follow-up if required.

addition, the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for a safe and dependable venue for IM trainees and attending physicians to voice questions and concerns about their patients. We observed the development of a shared mental model among all huddle participants, in the face of a steep learning curve on the management of patients with complex respiratory needs. This was reflected in the survey: Most respondents reported improved knowledge and confidence in managing these patients. Situational awareness that arose from the huddle provided the PCCM faculty the opportunity to guide the inpatient ward teams on next steps whether it be escalation to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Facilitation of transitions of care were voiced as challenging decisions faced by the inpatient ward teams, and there was appreciation for additional support from the PCCM faculty in making these difficult decisions.

Challenges and Opportunities

This was a single-center experience caring for veterans. Challenges with having virtual huddles during the COVID-19 surge involved both time for the health care practitioners and technology. This was recognized early by the educational leaders at our facility, and headsets and cameras were purchased for the team rooms and made available as quickly as possible. Another limitation was the unpredictability and variability of patient volume for specific teams that sometimes would affect the efficiency of the huddle. The number of teams who attended the COVID-19 huddle was highest for the first 2 weeks (maximum of 9 teams) but declined to a nadir of 3 at the end of the month. This reflected the increase in knowledge about COVID-19 and respiratory disease that the teams acquired initially as well as a decline in COVID-19 patient admissions over those weeks.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program model also can be expanded to include other frontline clinicians, including nurses and respiratory therapists. For example, case management huddles were performed in a similar way during the COVID-19 surge to allow for efficient and effective multidisciplinary conversations about patients

Conclusions

Given the rise of telemedicine and availability of video conferencing services, virtual huddles can be implemented in institutions with appropriate staff and remote access to health records. Multidisciplinary consultation services using video conferencing can serve as an adjunct to the traditional, in-person consultation service model for patients with complex needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all of the Baylor Internal Medicine house staff and internal medicine attendings who participated in our huddle and more importantly, cared for our veterans during this COVID-19 surge.

1. Heymann DL, Shindo N; WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: what is next for public health?. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):542-545. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

2. Dichter JR, Kanter RK, Dries D, et al; Task Force for Mass Critical Care. System-level planning, coordination, and communication: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(suppl 4):e87S-e102S. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0738

3. Chowdhury JM, Patel M, Zheng M, Abramian O, Criner GJ. Mobilization and preparation of a large urban academic center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(8):922-925. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-259PS

4. Uppal A, Silvestri DM, Siegler M, et al. Critical care and emergency department response at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1443-1449. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00901

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center- Houston, Texas. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/about

6. Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, McDaniel RR Jr, Pugh J. Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):2-12. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009

7. Franklin BJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team huddles on patient safety: a systematic review and proposed taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(10):1-2. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009911

8. Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM, Muething SE. Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):899-906. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467

1. Heymann DL, Shindo N; WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: what is next for public health?. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):542-545. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

2. Dichter JR, Kanter RK, Dries D, et al; Task Force for Mass Critical Care. System-level planning, coordination, and communication: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(suppl 4):e87S-e102S. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0738

3. Chowdhury JM, Patel M, Zheng M, Abramian O, Criner GJ. Mobilization and preparation of a large urban academic center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(8):922-925. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-259PS

4. Uppal A, Silvestri DM, Siegler M, et al. Critical care and emergency department response at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1443-1449. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00901

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center- Houston, Texas. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/about

6. Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, McDaniel RR Jr, Pugh J. Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):2-12. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009

7. Franklin BJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team huddles on patient safety: a systematic review and proposed taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(10):1-2. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009911

8. Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM, Muething SE. Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):899-906. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467