User login

Using Democratic Deliberation to Engage Veterans in Complex Policy Making for the Veterans Health Administration

Providing high-quality, patient-centered health care is a top priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Health Administration (VHA), whose core mission is to improve the health and well-being of US veterans. Thus, news of long wait times for medical appointments in the VHA sparked intense national attention and debate and led to changes in senior management and legislative action. 1 On August 8, 2014, President Bara c k Obama signed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, also known as the Choice Act, which provided an additional $16 billion in emergency spending over 3 years to improve veterans’ access to timely health care. 2 The Choice Act sought to develop an integrated health care network that allowed qualified VHA patients to receive specific health care services in their communities delivered by non-VHA health care providers (HCPs) but paid for by the VHA. The Choice Act also laid out explicit criteria for how to prioritize who would be eligible for VHA-purchased civilian care: (1) veterans who could not get timely appointments at a VHA medical facility within 30 days of referral; or (2) veterans who lived > 40 miles from the closest VHA medical facility.

VHA decision makers seeking to improve care delivery also need to weigh trade-offs between alternative approaches to providing rapid access. For instance, increasing access to non-VHA HCPs may not always decrease wait times and could result in loss of continuity, limited care coordination, limited ability to ensure and enforce high-quality standards at the VHA, and other challenges.3-6 Although the concerns and views of elected representatives, advocacy groups, and health system leaders are important, it is unknown whether these views and preferences align with those of veterans. Arguably, the range of views and concerns of informed veterans whose health is at stake should be particularly prominent in such policy decision making.

To identify the considerations that were most important to veterans regarding VHA policy around decreasing wait times, a study was designed to engage a group of veterans who were eligible for civilian care under the Choice Act. The study took place 1 year after the Choice Act was passed. Veterans were asked to focus on 2 related questions: First, how should funding be used for building VHA capacity (build) vs purchasing civilian care (buy)? Second, under what circumstances should civilian care be prioritized?

The aim of this paper is to describe democratic deliberation (DD), a specific method that engaged veteran patients in complex policy decisions around access to care. DD methods have been used increasingly in health care for developing policy guidance, setting priorities, providing advice on ethical dilemmas, weighing risk-benefit trade-offs, and determining decision-making authority.7-12 For example, DD helped guide national policy for mammography screening for breast cancer in New Zealand.13 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has completed a systematic review and a large, randomized experiment on best practices for carrying out public deliberation.8,13,14 However, despite the potential value of this approach, there has been little use of deliberative methods within the VHA for the explicit purpose of informing veteran health care delivery.

This paper describes the experience engaging veterans by using DD methodology and informing VHA leadership about the results of those deliberations. The specific aims were to understand whether DD is an acceptable approach to use to engage patients in the medical services policy-making process within VHA and whether veterans are able to come to an informed consensus.

Methods

Engaging patients and incorporating their needs and concerns within the policy-making process may improve health system policies and make those policies more patient centered. Such engagement also could be a way to generate creative solutions. However, because health-system decisions often involve making difficult trade-offs, effectively obtaining patient population input on complex care delivery issues can be challenging.

Although surveys can provide intuitive, top-of-mind input from respondents, these opinions are generally not sufficient for resolving complex problems.15 Focus groups and interviews may produce results that are more in-depth than surveys, but these methods tend to elicit settled private preferences rather than opinions about what the community should do.16 DD, on the other hand, is designed to elicit deeply informed public opinions on complex, value-laden topics to develop recommendations and policies for a larger community.17 The goal is to find collective solutions to challenging social problems. DD achieves this by giving participants an opportunity to explore a topic in-depth, question experts, and engage peers in reason-based discussions.18,19 This method has its roots in political science and has been used over several decades to successfully inform policy making on a broad array of topics nationally and internationally—from health research ethics in the US to nuclear and energy policy in Japan.7,16,20,21 DD has been found to promote ownership of public programs and lend legitimacy to policy decisions, political institutions, and democracy itself.18

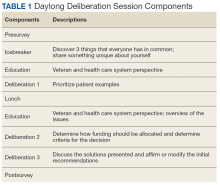

A single day (8 hours) DD session was convened, following a Citizens Jury model of deliberation, which brings veteran patients together to learn about a topic, ask questions of experts, deliberate with peers, and generate a “citizen’s report” that contains a set of recommendations (Table 1). An overview of the different models of DD and rationale for each can be found elsewhere.8,15

Recruitment Considerations

A purposively selected sample of civilian care-eligible veterans from a midwestern VHA health care system (1 medical center and 3 community-based outpatient clinics [CBOCs]) were invited to the DD session. The targeted number of participants was 30. Female veterans, who comprise only 7% of the local veteran population, were oversampled to account for their potentially different health care needs and to create balance between males and females in the session. Oversampling for other characteristics was not possible due to the relatively small sample size. Based on prior experience,7 it was assumed that 70% of willing participants would attend the session; therefore 34 veterans were invited and 24 attended. Each participant received a $200 incentive in appreciation for their substantial time commitment and to offset transportation costs.

Background Materials

A packet with educational materials (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 10.5) was mailed to participants about 2 weeks before the DD session. Participants were asked to review prior to attending the session. These materials described the session (eg, purpose, organizers, importance) and provided factual information about the Choice Act (eg, eligibility, out-of-pocket costs, travel pay, prescription drug policies).

Session Overview

The session was structured to accomplish the following goals: (1) Elicit participants’ opinions about access to health care and reasons for those opinions; (2) Provide in-depth education about the Choice Act through presentations and discussions with topical experts; and (3) Elicit reasoning and recommendations on both the criteria by which participants prioritize candidates for civilian care and how participants would allocate additional funding to improve access (ie, by building VHA capacity to deliver more timely health care vs purchasing health care from civilian HCPs).

Participants were asked to fill out a survey on arrival in the morning and were assigned to 1 of 3 tables or small groups. Each table had a facilitator who had extensive experience in qualitative data collection methods and guided the dialogue using a scripted protocol that they helped develop and refine. The facilitation materials drew from and used previously published studies.22,23 Each facilitator audio recorded the sessions and took notes. Three experts presented during plenary education sessions. Presentations were designed to provide balanced factual information and included a veteran’s perspective. One presenter was a clinician on the project team, another was a local clinical leader responsible for making decisions about what services to provide via civilian care (buy) vs enhancing the local VHA health system’s ability to provide those services (build), and the third presenter was a veteran who was on the project team.

Education Session 1

The first plenary education session with expert presentations was conducted after each table completed an icebreaker exercise. The project team physician provided a brief history and description of the Choice Act to reinforce educational materials sent to participants prior to the session. The health system clinical leader described his decision process and principles and highlighted constraints placed on him by the Choice Act that were in place at the time of the DD session. He also described existing local and national programs to provide civilian care (eg, local fee-basis non-VHA care programs) and how these programs sought to achieve goals similar to the Choice Act. The veteran presenter focused on the importance of session participants providing candid insight and observations and emphasized that this session was a significant opportunity to “have their voices heard.”

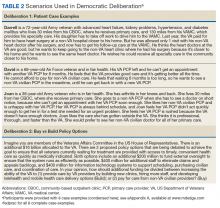

Deliberation 1: What criteria should be used to prioritize patients for receiving civilian care paid for by the VHA? To elicit preferences on the central question of this deliberation, participants were presented with 8 real-world cases that were based on interviews conducted with Choice Act-eligible veterans (Table 2 and eAppendices A

Education Session 2

In the second plenary session, the project team physician provided information about health care access issues, both inside and outside of the VHA, particularly between urban and rural areas. He also discussed factors related to the insufficient capacity to meet growing demand that contributed to the VHA wait-time crisis. The veteran presenter shared reflections on health care access from a veteran’s perspective.

Deliberation 2: How should additional funding be divided between increasing the ability of the VHA to (1) provide care by VHA HCPs; and (2) pay for care from non-VHA civilian HCPs? Participants were presented the patient examples and Choice Act funding scenarios (the buy policy option) and contrasted that with a build policy option. Participants were explicitly encouraged to shift their perspectives from thinking about individual cases to considering policy-level decisions and the broader social good (Table 2).

Ensuring Robust Deliberations

If participants do not adequately grasp the complexities of the topic, a deliberation can fail. To facilitate nuanced reasoning, real-world concrete examples were developed as the starting point of each deliberation based on interviews with actual patients (deliberation 1) and actual policy proposals relevant to the funding allocation decisions within the Choice Act (deliberation 2).

A deliberation also can fail with self-silencing, where participants withhold opinions that differ from those articulated first or by more vocal members of the group.24 To combat self-silencing, highly experienced facilitators were used to ensure sharing from all participants and to support an open-minded, courteous, and reason-based environment for discourse. It was specified that the best solutions are achieved through reason-based and cordial disagreement and that success can be undermined when participants simply agree because it is easier or more comfortable.

A third way a deliberation can fail is if individuals do not adopt a group or system-level perspective. To counter this, facilitators reinforced at multiple points the importance of taking a broader social perspective rather than sharing only one’s personal preferences.

Finally, it is important to assess the quality of the deliberative process itself, to ensure that results are trustworthy.25 To assess the quality of the deliberative process, participants knowledge about key issues pre- and postdeliberation were assessed. Participants also were asked to rate the quality of the facilitators and how well they felt their voice was heard and respected, and facilitators made qualitative assessments about the extent to which participants were engaged in reason-based and collaborative discussion.

Data

Quantitative data were collected via pre- and postsession surveys. The surveys contained items related to knowledge about the Choice Act, expectations for the DD session, beliefs and opinions about the provision of health care for veterans, recommended funding allocations between build vs buy policy options, and general demographics. Qualitative data were collected through detailed notes taken by the 3 facilitators. Each table’s deliberations were audio recorded so that gaps in the notes could be filled.

The 3 facilitators, who were all experienced qualitative researchers, typed their written notes into a template immediately after the session. Two of the 3 facilitators led the analysis of the session notes. Findings within and across the 3 deliberation tables were developed using content and matrix analysis methods.26 Descriptive statistics were generated from survey responses and compared survey items pre- and postsession using paired t tests or χ2 tests for categorical responses.

Results

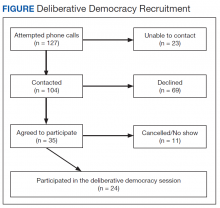

Thirty-three percent of individuals invited (n = 127) agreed to participate. Those who declined cited conflicts related to distance, transportation, work/school, medical appointments, family commitments, or were not interested. In all, 24 (69%) of the 35 veterans who accepted the invitation attended the deliberation session. Of the 11 who accepted but did not attend, 5 cancelled ahead of time because of conflicts (Figure). Most participants were male (70%), 48% were aged 61 to 75 years, 65% were white, 43% had some college education, 43% reported an annual income of between $25,000 and $40,000, and only 35% reported very good health (eAppendix D).

Deliberation 1

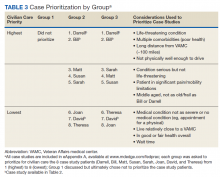

During the deliberation on the prioritization criteria, the concept of “condition severity” emerged as an important criterion for veterans. This criterion captured simultaneous consideration of both clinical necessity and burden on the veteran to obtain care. For example, participants felt that patients with a life-threatening illness should be prioritized for civilian care over patients who need preventative or primary care (clinical necessity) and that elderly patients with substantial difficulty traveling to VHA appointments should be prioritized over patients who can travel more easily (burden). The Choice Act regulations at the time of the DD session did not reflect this nuanced perspective, stipulating only that veterans must live > 40 miles from the nearest VHA medical facility.

One of the 3 groups did not prioritize the patient cases because some members felt that no veteran should be constrained from receiving civilian care if they desired it. Nonetheless, this group did agree with prioritizing the first 2 cases in Table 3. The other groups prioritized all 8 cases in generally similar ways.

Deliberation 2

No clear consensus emerged on the buy vs build question. A representative from each table presented their group’s positions, rationale, and recommendations after deliberations were completed. After hearing the range of positions, the groups then had another opportunity to deliberate based on what they heard from the other tables; no new recommendations or consensus emerged.

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the build policy offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) increase access for rural veterans by building CBOCs and deploying more mobile units that could bring outlets for health care closer to their home communities; (2) provide critical and unique medical expertise to address veteran-specific issues such as prosthetics, traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, spinal cord injury, and shrapnel wounds that are typically not available through civilian providers; (3) give VHA more oversight over the quality and cost of care, which is more challenging to do with civilian providers; and (4) Improve VHA infrastructure by, for example, upgrading technology and attracting the best clinicians and staff to support “our VHA.”

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the buy policy also offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) decrease patient burden by increasing access through community providers, decreasing wait time, and lessening personal cost and travel time; (2) allow more patients to receive civilian care, which was generally seen as beneficial by a few participants because of perceptions that the VHA provides lower quality care due to a shortage of VHA providers, run-down/older facilities, lack of technology, and poorer-quality VHA providers; and (3) provide an opportunity to divest of costly facilities and invest in other innovative approaches. Regarding this last reason, a few participants felt that the VHA is “gouged” when building medical centers that overrun budgets. They also were concerned that investing in facilities tied VHA to specific locations when current locations of veterans may change “25 years from now.”

Survey Results

Twenty-three of the 24 participants completed both pre- and postsession surveys. The majority of participants in the session felt people in the group respected their opinion (96%); felt that the facilitator did not try to influence the group with her own opinions (96%); indicated they understood the information enough to participate as much as they wanted (100%); and were hopeful that their reasoning and recommendations would help inform VHA policy makers (82%).

The surveys also provided an opportunity to examine the extent to which knowledge, attitudes, and opinions changed from before to after the deliberation. Even with the small sample, responses revealed a trend toward improved knowledge about key elements of the Choice Act and its goals. Further, there was a shift in some participants’ opinions about how patients should be prioritized to receive civilian care. For example, before the deliberation participants generally felt that all veterans should be able to receive civilian care, whereas postdeliberation this was not the case. Postdeliberation, most participants felt that primary care should not be a high priority for civilian care but continued to endorse prioritizing civilian care for specialty services like orthopedic or cardiology-related care. Finally, participants moved from more diverse recommendations regarding additional funds allocations, toward consensus after the deliberation around allocating funds to the build policy. Eight participants supported a build policy beforehand, whereas 16 supported this policy afterward.

Discussion

This study explored DD as a method for deeply engaging veterans in complex policy making to guide funding allocation and prioritization decisions related to the Choice Act, decisions that are still very relevant today within the context of the Mission Act and have substantial implications for how health care is delivered in the VHA. The Mission Act passed on June 6, 2018, with the goal of improving access to and the reliability of civilian or community care for eligible veterans.27 Decisions related to appropriating scarce funding to improve access to care is an emotional and value-laden topic that elicited strong and divergent opinions among the participants. Veterans were eager to have their voices heard and had strong expectations that VHA leadership would be briefed about their recommendations. The majority of participants were satisfied with the deliberation process, felt they understood the issues, and felt their opinions were respected. They expressed feelings of comradery and community throughout the process.

In this single deliberation session, the groups did not achieve a single, final consensus regarding how VHA funding should ultimately be allocated between buy and build policy options. Nonetheless, participants provided a rich array of recommendations and rationale for them. Session moderators observed rich, sophisticated, fair, and reason-based discussions on this complex topic. Participants left with a deeper knowledge and appreciation for the complex trade-offs and expressed strong rationales for both sides of the policy debate on build vs buy. In addition, the project yielded results of high interest to VHA policy makers.

This work was presented in multiple venues between 2015 to 2016, and to both local and national VHA leadership, including the local Executive Quality Leadership Boards, the VHA Central Office Committee on the Future State of VA Community Care, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care, and the National Veteran Experience Committee. Through these discussions and others, we saw great interest within the VHA system and high-level leaders to explore ways to include veterans’ voices in the policy-making process. This work was invaluable to our research team (eAppendix E

Many health system decisions regarding what care should be delivered (and how) involve making difficult, value-laden choices in the context of limited resources. DD methods can be used to target and obtain specific viewpoints from diverse populations, such as the informed perspectives of minority and underrepresented populations within the VHA.19 For example, female veterans were oversampled to ensure that the informed preferences of this population was obtained. Thus, DD methods could provide a valuable tool for health systems to elicit in-depth diverse patient input on high-profile policies that will have a substantial impact on the system’s patient population.

Limitations

One potential downside of DD is that, because of the resource-intensive nature of deliberation sessions, they are often conducted with relatively small groups.9 Viewpoints of those within these small samples who are willing to spend an entire day discussing a complex topic may not be representative of the larger patient community. However, the core goal of DD is diversity of opinions rather than representativeness.

A stratified random sampling strategy that oversampled for underrepresented and minority populations was used to help select a diverse group that represents the population on key characteristics and partially addresses concern about representativeness. Efforts to optimize participation rates, including providing monetary incentives, also are helpful and have led to high participation rates in past deliberations.7

Health system communication strategies that promote the importance of becoming involved in DD sessions also may be helpful in improving rates of recruitment. On particularly important topics where health system leaders feel a larger resource investment is justified, conducting larger scale deliberations with many small groups may obtain more generalizable evidence about what individual patients and groups of patients recommend.7 However, due to the inherent limitations of surveys and focus group approaches for obtaining informed views on complex topics, there are no clear systematic alternatives to the DD approach.

Conclusion

DD is an effective method to meaningfully engage patients in deep deliberations to guide complex policy making. Although design of deliberative sessions is resource-intensive, patient engagement efforts, such as those described in this paper, could be an important aspect of a well-functioning learning health system. Further research into alternative, streamlined methods that can also engage veterans more deeply is needed. DD also can be combined with other approaches to broaden and confirm findings, including focus groups, town hall meetings, or surveys.

Although this study did not provide consensus on how the VHA should allocate funds with respect to the Choice Act, it did provide insight into the importance and feasibility of engaging veterans in the policy-making process. As more policies aimed at improving veterans’ access to civilian care are created, such as the most recent Mission Act, policy makers should strongly consider using the DD method of obtaining informed veteran input into future policy decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence (OABI) and the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). Dr. Caverly was supported in part by a VA Career Development Award (CDA 16-151). Dr. Krein is supported by a VA Health Services Research and Development Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 11-222). The authors thank the veterans who participated in this work. They also thank Caitlin Reardon and Natalya Wawrin for their assistance in organizing the deliberation session.

1. VA Office of the Inspector General. Veterans Health Administration. Interim report: review of patient wait times, scheduling practices, and alleged patient deaths at the Phoenix Health Care System. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-14-02603-178.pdf. Published May 28, 2014. Accessed December 9, 2019.

2. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. 42 USC §1395 (2014).

3. Penn M, Bhatnagar S, Kuy S, et al. Comparison of wait times for new patients between the private sector and United States Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187096.

4. Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Schleiden L, et al. Association between dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D drug benefits and potentially unsafe prescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2019; July 22. [Epub ahead of print.]

5. Moyo P, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, et al. Dual receipt of prescription opioids from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D and prescription opioid overdose death among veterans: a nested case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(7):433-442.

6. Meyer LJ, Clancy CM. Care fragmentation and prescription opioids. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(7):497-498.

7. Damschroder LJ, Pritts JL, Neblo MA, Kalarickal RJ, Creswell JW, Hayward RA. Patients, privacy and trust: patients’ willingness to allow researchers to access their medical records. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(1):223-235.

8. Street J, Duszynski K, Krawczyk S, Braunack-Mayer A. The use of citizens’ juries in health policy decision-making: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;109:1-9.

9. Paul C, Nicholls R, Priest P, McGee R. Making policy decisions about population screening for breast cancer: the role of citizens’ deliberation. Health Policy. 2008;85(3):314-320.

10. Martin D, Abelson J, Singer P. Participation in health care priority-setting through the eyes of the participants. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2002;7(4):222-229.

11. Mort M, Finch T. Principles for telemedicine and telecare: the perspective of a citizens’ panel. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11(suppl 1):66-68.

12. Kass N, Faden R, Fabi RE, et al. Alternative consent models for comparative effectiveness studies: views of patients from two institutions. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2016;7(2):92-105.

13. Carman KL, Mallery C, Maurer M, et al. Effectiveness of public deliberation methods for gathering input on issues in healthcare: results from a randomized trial. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:11-20.

14. Carman KL, Maurer M, Mangrum R, et al. Understanding an informed public’s views on the role of evidence in making health care decisions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):566-574.

15. Kim SYH, Wall IF, Stanczyk A, De Vries R. Assessing the public’s views in research ethics controversies: deliberative democracy and bioethics as natural allies, J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4(4):3-16.

16. Gastil J, Levine P, eds. The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

17. Dryzek JS, Bächtiger A, Chambers S, et al. The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science. 2019;363(6432):1144-1146.

18. Blacksher E, Diebel A, Forest PG, Goold SD, Abelson J. What is public deliberation? Hastings Cent Rep. 2012;4(2):14-17.

19. Wang G, Gold M, Siegel J, et al. Deliberation: obtaining informed input from a diverse public. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(1):223-242.

20. Simon RL, ed. The Blackwell Guide to Social and Political Philosophy. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2002.

21. Stanford University, Center for Deliberative Democracy. Deliberative polling on energy and environmental policy options in Japan. https://cdd.stanford.edu/2012/deliberative-polling-on-energy-and-environmental-policy-options-in-japan. Published August 12, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2019.

22. Damschroder LJ, Pritts JL, Neblo MA, Kalarickal RJ, Creswell JW, Hayward RA. Patients, privacy and trust: patients’ willingness to allow researchers to access their medical records. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(1):223-235.

23. Carman KL, Maurer M, Mallery C, et al. Community forum deliberative methods demonstration: evaluating effectiveness and eliciting public views on use of evidence. Final report. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/deliberative-methods_research-2013-1.pdf. Published November 2014. Accessed December 9, 2019.

24. Sunstein CR, Hastie R. Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

25. Damschroder LJ, Kim SY. Assessing the quality of democratic deliberation: a case study of public deliberation on the ethics of surrogate consent for research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):1896-1903.

26. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1994.

27. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran community care – general information. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/pubfiles/factsheets/VHA-FS_MISSION-Act.pdf. Published September 9 2019. Accessed December 9, 2019.

Providing high-quality, patient-centered health care is a top priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Health Administration (VHA), whose core mission is to improve the health and well-being of US veterans. Thus, news of long wait times for medical appointments in the VHA sparked intense national attention and debate and led to changes in senior management and legislative action. 1 On August 8, 2014, President Bara c k Obama signed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, also known as the Choice Act, which provided an additional $16 billion in emergency spending over 3 years to improve veterans’ access to timely health care. 2 The Choice Act sought to develop an integrated health care network that allowed qualified VHA patients to receive specific health care services in their communities delivered by non-VHA health care providers (HCPs) but paid for by the VHA. The Choice Act also laid out explicit criteria for how to prioritize who would be eligible for VHA-purchased civilian care: (1) veterans who could not get timely appointments at a VHA medical facility within 30 days of referral; or (2) veterans who lived > 40 miles from the closest VHA medical facility.

VHA decision makers seeking to improve care delivery also need to weigh trade-offs between alternative approaches to providing rapid access. For instance, increasing access to non-VHA HCPs may not always decrease wait times and could result in loss of continuity, limited care coordination, limited ability to ensure and enforce high-quality standards at the VHA, and other challenges.3-6 Although the concerns and views of elected representatives, advocacy groups, and health system leaders are important, it is unknown whether these views and preferences align with those of veterans. Arguably, the range of views and concerns of informed veterans whose health is at stake should be particularly prominent in such policy decision making.

To identify the considerations that were most important to veterans regarding VHA policy around decreasing wait times, a study was designed to engage a group of veterans who were eligible for civilian care under the Choice Act. The study took place 1 year after the Choice Act was passed. Veterans were asked to focus on 2 related questions: First, how should funding be used for building VHA capacity (build) vs purchasing civilian care (buy)? Second, under what circumstances should civilian care be prioritized?

The aim of this paper is to describe democratic deliberation (DD), a specific method that engaged veteran patients in complex policy decisions around access to care. DD methods have been used increasingly in health care for developing policy guidance, setting priorities, providing advice on ethical dilemmas, weighing risk-benefit trade-offs, and determining decision-making authority.7-12 For example, DD helped guide national policy for mammography screening for breast cancer in New Zealand.13 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has completed a systematic review and a large, randomized experiment on best practices for carrying out public deliberation.8,13,14 However, despite the potential value of this approach, there has been little use of deliberative methods within the VHA for the explicit purpose of informing veteran health care delivery.

This paper describes the experience engaging veterans by using DD methodology and informing VHA leadership about the results of those deliberations. The specific aims were to understand whether DD is an acceptable approach to use to engage patients in the medical services policy-making process within VHA and whether veterans are able to come to an informed consensus.

Methods

Engaging patients and incorporating their needs and concerns within the policy-making process may improve health system policies and make those policies more patient centered. Such engagement also could be a way to generate creative solutions. However, because health-system decisions often involve making difficult trade-offs, effectively obtaining patient population input on complex care delivery issues can be challenging.

Although surveys can provide intuitive, top-of-mind input from respondents, these opinions are generally not sufficient for resolving complex problems.15 Focus groups and interviews may produce results that are more in-depth than surveys, but these methods tend to elicit settled private preferences rather than opinions about what the community should do.16 DD, on the other hand, is designed to elicit deeply informed public opinions on complex, value-laden topics to develop recommendations and policies for a larger community.17 The goal is to find collective solutions to challenging social problems. DD achieves this by giving participants an opportunity to explore a topic in-depth, question experts, and engage peers in reason-based discussions.18,19 This method has its roots in political science and has been used over several decades to successfully inform policy making on a broad array of topics nationally and internationally—from health research ethics in the US to nuclear and energy policy in Japan.7,16,20,21 DD has been found to promote ownership of public programs and lend legitimacy to policy decisions, political institutions, and democracy itself.18

A single day (8 hours) DD session was convened, following a Citizens Jury model of deliberation, which brings veteran patients together to learn about a topic, ask questions of experts, deliberate with peers, and generate a “citizen’s report” that contains a set of recommendations (Table 1). An overview of the different models of DD and rationale for each can be found elsewhere.8,15

Recruitment Considerations

A purposively selected sample of civilian care-eligible veterans from a midwestern VHA health care system (1 medical center and 3 community-based outpatient clinics [CBOCs]) were invited to the DD session. The targeted number of participants was 30. Female veterans, who comprise only 7% of the local veteran population, were oversampled to account for their potentially different health care needs and to create balance between males and females in the session. Oversampling for other characteristics was not possible due to the relatively small sample size. Based on prior experience,7 it was assumed that 70% of willing participants would attend the session; therefore 34 veterans were invited and 24 attended. Each participant received a $200 incentive in appreciation for their substantial time commitment and to offset transportation costs.

Background Materials

A packet with educational materials (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 10.5) was mailed to participants about 2 weeks before the DD session. Participants were asked to review prior to attending the session. These materials described the session (eg, purpose, organizers, importance) and provided factual information about the Choice Act (eg, eligibility, out-of-pocket costs, travel pay, prescription drug policies).

Session Overview

The session was structured to accomplish the following goals: (1) Elicit participants’ opinions about access to health care and reasons for those opinions; (2) Provide in-depth education about the Choice Act through presentations and discussions with topical experts; and (3) Elicit reasoning and recommendations on both the criteria by which participants prioritize candidates for civilian care and how participants would allocate additional funding to improve access (ie, by building VHA capacity to deliver more timely health care vs purchasing health care from civilian HCPs).

Participants were asked to fill out a survey on arrival in the morning and were assigned to 1 of 3 tables or small groups. Each table had a facilitator who had extensive experience in qualitative data collection methods and guided the dialogue using a scripted protocol that they helped develop and refine. The facilitation materials drew from and used previously published studies.22,23 Each facilitator audio recorded the sessions and took notes. Three experts presented during plenary education sessions. Presentations were designed to provide balanced factual information and included a veteran’s perspective. One presenter was a clinician on the project team, another was a local clinical leader responsible for making decisions about what services to provide via civilian care (buy) vs enhancing the local VHA health system’s ability to provide those services (build), and the third presenter was a veteran who was on the project team.

Education Session 1

The first plenary education session with expert presentations was conducted after each table completed an icebreaker exercise. The project team physician provided a brief history and description of the Choice Act to reinforce educational materials sent to participants prior to the session. The health system clinical leader described his decision process and principles and highlighted constraints placed on him by the Choice Act that were in place at the time of the DD session. He also described existing local and national programs to provide civilian care (eg, local fee-basis non-VHA care programs) and how these programs sought to achieve goals similar to the Choice Act. The veteran presenter focused on the importance of session participants providing candid insight and observations and emphasized that this session was a significant opportunity to “have their voices heard.”

Deliberation 1: What criteria should be used to prioritize patients for receiving civilian care paid for by the VHA? To elicit preferences on the central question of this deliberation, participants were presented with 8 real-world cases that were based on interviews conducted with Choice Act-eligible veterans (Table 2 and eAppendices A

Education Session 2

In the second plenary session, the project team physician provided information about health care access issues, both inside and outside of the VHA, particularly between urban and rural areas. He also discussed factors related to the insufficient capacity to meet growing demand that contributed to the VHA wait-time crisis. The veteran presenter shared reflections on health care access from a veteran’s perspective.

Deliberation 2: How should additional funding be divided between increasing the ability of the VHA to (1) provide care by VHA HCPs; and (2) pay for care from non-VHA civilian HCPs? Participants were presented the patient examples and Choice Act funding scenarios (the buy policy option) and contrasted that with a build policy option. Participants were explicitly encouraged to shift their perspectives from thinking about individual cases to considering policy-level decisions and the broader social good (Table 2).

Ensuring Robust Deliberations

If participants do not adequately grasp the complexities of the topic, a deliberation can fail. To facilitate nuanced reasoning, real-world concrete examples were developed as the starting point of each deliberation based on interviews with actual patients (deliberation 1) and actual policy proposals relevant to the funding allocation decisions within the Choice Act (deliberation 2).

A deliberation also can fail with self-silencing, where participants withhold opinions that differ from those articulated first or by more vocal members of the group.24 To combat self-silencing, highly experienced facilitators were used to ensure sharing from all participants and to support an open-minded, courteous, and reason-based environment for discourse. It was specified that the best solutions are achieved through reason-based and cordial disagreement and that success can be undermined when participants simply agree because it is easier or more comfortable.

A third way a deliberation can fail is if individuals do not adopt a group or system-level perspective. To counter this, facilitators reinforced at multiple points the importance of taking a broader social perspective rather than sharing only one’s personal preferences.

Finally, it is important to assess the quality of the deliberative process itself, to ensure that results are trustworthy.25 To assess the quality of the deliberative process, participants knowledge about key issues pre- and postdeliberation were assessed. Participants also were asked to rate the quality of the facilitators and how well they felt their voice was heard and respected, and facilitators made qualitative assessments about the extent to which participants were engaged in reason-based and collaborative discussion.

Data

Quantitative data were collected via pre- and postsession surveys. The surveys contained items related to knowledge about the Choice Act, expectations for the DD session, beliefs and opinions about the provision of health care for veterans, recommended funding allocations between build vs buy policy options, and general demographics. Qualitative data were collected through detailed notes taken by the 3 facilitators. Each table’s deliberations were audio recorded so that gaps in the notes could be filled.

The 3 facilitators, who were all experienced qualitative researchers, typed their written notes into a template immediately after the session. Two of the 3 facilitators led the analysis of the session notes. Findings within and across the 3 deliberation tables were developed using content and matrix analysis methods.26 Descriptive statistics were generated from survey responses and compared survey items pre- and postsession using paired t tests or χ2 tests for categorical responses.

Results

Thirty-three percent of individuals invited (n = 127) agreed to participate. Those who declined cited conflicts related to distance, transportation, work/school, medical appointments, family commitments, or were not interested. In all, 24 (69%) of the 35 veterans who accepted the invitation attended the deliberation session. Of the 11 who accepted but did not attend, 5 cancelled ahead of time because of conflicts (Figure). Most participants were male (70%), 48% were aged 61 to 75 years, 65% were white, 43% had some college education, 43% reported an annual income of between $25,000 and $40,000, and only 35% reported very good health (eAppendix D).

Deliberation 1

During the deliberation on the prioritization criteria, the concept of “condition severity” emerged as an important criterion for veterans. This criterion captured simultaneous consideration of both clinical necessity and burden on the veteran to obtain care. For example, participants felt that patients with a life-threatening illness should be prioritized for civilian care over patients who need preventative or primary care (clinical necessity) and that elderly patients with substantial difficulty traveling to VHA appointments should be prioritized over patients who can travel more easily (burden). The Choice Act regulations at the time of the DD session did not reflect this nuanced perspective, stipulating only that veterans must live > 40 miles from the nearest VHA medical facility.

One of the 3 groups did not prioritize the patient cases because some members felt that no veteran should be constrained from receiving civilian care if they desired it. Nonetheless, this group did agree with prioritizing the first 2 cases in Table 3. The other groups prioritized all 8 cases in generally similar ways.

Deliberation 2

No clear consensus emerged on the buy vs build question. A representative from each table presented their group’s positions, rationale, and recommendations after deliberations were completed. After hearing the range of positions, the groups then had another opportunity to deliberate based on what they heard from the other tables; no new recommendations or consensus emerged.

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the build policy offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) increase access for rural veterans by building CBOCs and deploying more mobile units that could bring outlets for health care closer to their home communities; (2) provide critical and unique medical expertise to address veteran-specific issues such as prosthetics, traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, spinal cord injury, and shrapnel wounds that are typically not available through civilian providers; (3) give VHA more oversight over the quality and cost of care, which is more challenging to do with civilian providers; and (4) Improve VHA infrastructure by, for example, upgrading technology and attracting the best clinicians and staff to support “our VHA.”

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the buy policy also offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) decrease patient burden by increasing access through community providers, decreasing wait time, and lessening personal cost and travel time; (2) allow more patients to receive civilian care, which was generally seen as beneficial by a few participants because of perceptions that the VHA provides lower quality care due to a shortage of VHA providers, run-down/older facilities, lack of technology, and poorer-quality VHA providers; and (3) provide an opportunity to divest of costly facilities and invest in other innovative approaches. Regarding this last reason, a few participants felt that the VHA is “gouged” when building medical centers that overrun budgets. They also were concerned that investing in facilities tied VHA to specific locations when current locations of veterans may change “25 years from now.”

Survey Results

Twenty-three of the 24 participants completed both pre- and postsession surveys. The majority of participants in the session felt people in the group respected their opinion (96%); felt that the facilitator did not try to influence the group with her own opinions (96%); indicated they understood the information enough to participate as much as they wanted (100%); and were hopeful that their reasoning and recommendations would help inform VHA policy makers (82%).

The surveys also provided an opportunity to examine the extent to which knowledge, attitudes, and opinions changed from before to after the deliberation. Even with the small sample, responses revealed a trend toward improved knowledge about key elements of the Choice Act and its goals. Further, there was a shift in some participants’ opinions about how patients should be prioritized to receive civilian care. For example, before the deliberation participants generally felt that all veterans should be able to receive civilian care, whereas postdeliberation this was not the case. Postdeliberation, most participants felt that primary care should not be a high priority for civilian care but continued to endorse prioritizing civilian care for specialty services like orthopedic or cardiology-related care. Finally, participants moved from more diverse recommendations regarding additional funds allocations, toward consensus after the deliberation around allocating funds to the build policy. Eight participants supported a build policy beforehand, whereas 16 supported this policy afterward.

Discussion

This study explored DD as a method for deeply engaging veterans in complex policy making to guide funding allocation and prioritization decisions related to the Choice Act, decisions that are still very relevant today within the context of the Mission Act and have substantial implications for how health care is delivered in the VHA. The Mission Act passed on June 6, 2018, with the goal of improving access to and the reliability of civilian or community care for eligible veterans.27 Decisions related to appropriating scarce funding to improve access to care is an emotional and value-laden topic that elicited strong and divergent opinions among the participants. Veterans were eager to have their voices heard and had strong expectations that VHA leadership would be briefed about their recommendations. The majority of participants were satisfied with the deliberation process, felt they understood the issues, and felt their opinions were respected. They expressed feelings of comradery and community throughout the process.

In this single deliberation session, the groups did not achieve a single, final consensus regarding how VHA funding should ultimately be allocated between buy and build policy options. Nonetheless, participants provided a rich array of recommendations and rationale for them. Session moderators observed rich, sophisticated, fair, and reason-based discussions on this complex topic. Participants left with a deeper knowledge and appreciation for the complex trade-offs and expressed strong rationales for both sides of the policy debate on build vs buy. In addition, the project yielded results of high interest to VHA policy makers.

This work was presented in multiple venues between 2015 to 2016, and to both local and national VHA leadership, including the local Executive Quality Leadership Boards, the VHA Central Office Committee on the Future State of VA Community Care, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care, and the National Veteran Experience Committee. Through these discussions and others, we saw great interest within the VHA system and high-level leaders to explore ways to include veterans’ voices in the policy-making process. This work was invaluable to our research team (eAppendix E

Many health system decisions regarding what care should be delivered (and how) involve making difficult, value-laden choices in the context of limited resources. DD methods can be used to target and obtain specific viewpoints from diverse populations, such as the informed perspectives of minority and underrepresented populations within the VHA.19 For example, female veterans were oversampled to ensure that the informed preferences of this population was obtained. Thus, DD methods could provide a valuable tool for health systems to elicit in-depth diverse patient input on high-profile policies that will have a substantial impact on the system’s patient population.

Limitations

One potential downside of DD is that, because of the resource-intensive nature of deliberation sessions, they are often conducted with relatively small groups.9 Viewpoints of those within these small samples who are willing to spend an entire day discussing a complex topic may not be representative of the larger patient community. However, the core goal of DD is diversity of opinions rather than representativeness.

A stratified random sampling strategy that oversampled for underrepresented and minority populations was used to help select a diverse group that represents the population on key characteristics and partially addresses concern about representativeness. Efforts to optimize participation rates, including providing monetary incentives, also are helpful and have led to high participation rates in past deliberations.7

Health system communication strategies that promote the importance of becoming involved in DD sessions also may be helpful in improving rates of recruitment. On particularly important topics where health system leaders feel a larger resource investment is justified, conducting larger scale deliberations with many small groups may obtain more generalizable evidence about what individual patients and groups of patients recommend.7 However, due to the inherent limitations of surveys and focus group approaches for obtaining informed views on complex topics, there are no clear systematic alternatives to the DD approach.

Conclusion

DD is an effective method to meaningfully engage patients in deep deliberations to guide complex policy making. Although design of deliberative sessions is resource-intensive, patient engagement efforts, such as those described in this paper, could be an important aspect of a well-functioning learning health system. Further research into alternative, streamlined methods that can also engage veterans more deeply is needed. DD also can be combined with other approaches to broaden and confirm findings, including focus groups, town hall meetings, or surveys.

Although this study did not provide consensus on how the VHA should allocate funds with respect to the Choice Act, it did provide insight into the importance and feasibility of engaging veterans in the policy-making process. As more policies aimed at improving veterans’ access to civilian care are created, such as the most recent Mission Act, policy makers should strongly consider using the DD method of obtaining informed veteran input into future policy decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence (OABI) and the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). Dr. Caverly was supported in part by a VA Career Development Award (CDA 16-151). Dr. Krein is supported by a VA Health Services Research and Development Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 11-222). The authors thank the veterans who participated in this work. They also thank Caitlin Reardon and Natalya Wawrin for their assistance in organizing the deliberation session.

Providing high-quality, patient-centered health care is a top priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Health Administration (VHA), whose core mission is to improve the health and well-being of US veterans. Thus, news of long wait times for medical appointments in the VHA sparked intense national attention and debate and led to changes in senior management and legislative action. 1 On August 8, 2014, President Bara c k Obama signed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, also known as the Choice Act, which provided an additional $16 billion in emergency spending over 3 years to improve veterans’ access to timely health care. 2 The Choice Act sought to develop an integrated health care network that allowed qualified VHA patients to receive specific health care services in their communities delivered by non-VHA health care providers (HCPs) but paid for by the VHA. The Choice Act also laid out explicit criteria for how to prioritize who would be eligible for VHA-purchased civilian care: (1) veterans who could not get timely appointments at a VHA medical facility within 30 days of referral; or (2) veterans who lived > 40 miles from the closest VHA medical facility.

VHA decision makers seeking to improve care delivery also need to weigh trade-offs between alternative approaches to providing rapid access. For instance, increasing access to non-VHA HCPs may not always decrease wait times and could result in loss of continuity, limited care coordination, limited ability to ensure and enforce high-quality standards at the VHA, and other challenges.3-6 Although the concerns and views of elected representatives, advocacy groups, and health system leaders are important, it is unknown whether these views and preferences align with those of veterans. Arguably, the range of views and concerns of informed veterans whose health is at stake should be particularly prominent in such policy decision making.

To identify the considerations that were most important to veterans regarding VHA policy around decreasing wait times, a study was designed to engage a group of veterans who were eligible for civilian care under the Choice Act. The study took place 1 year after the Choice Act was passed. Veterans were asked to focus on 2 related questions: First, how should funding be used for building VHA capacity (build) vs purchasing civilian care (buy)? Second, under what circumstances should civilian care be prioritized?

The aim of this paper is to describe democratic deliberation (DD), a specific method that engaged veteran patients in complex policy decisions around access to care. DD methods have been used increasingly in health care for developing policy guidance, setting priorities, providing advice on ethical dilemmas, weighing risk-benefit trade-offs, and determining decision-making authority.7-12 For example, DD helped guide national policy for mammography screening for breast cancer in New Zealand.13 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has completed a systematic review and a large, randomized experiment on best practices for carrying out public deliberation.8,13,14 However, despite the potential value of this approach, there has been little use of deliberative methods within the VHA for the explicit purpose of informing veteran health care delivery.

This paper describes the experience engaging veterans by using DD methodology and informing VHA leadership about the results of those deliberations. The specific aims were to understand whether DD is an acceptable approach to use to engage patients in the medical services policy-making process within VHA and whether veterans are able to come to an informed consensus.

Methods

Engaging patients and incorporating their needs and concerns within the policy-making process may improve health system policies and make those policies more patient centered. Such engagement also could be a way to generate creative solutions. However, because health-system decisions often involve making difficult trade-offs, effectively obtaining patient population input on complex care delivery issues can be challenging.

Although surveys can provide intuitive, top-of-mind input from respondents, these opinions are generally not sufficient for resolving complex problems.15 Focus groups and interviews may produce results that are more in-depth than surveys, but these methods tend to elicit settled private preferences rather than opinions about what the community should do.16 DD, on the other hand, is designed to elicit deeply informed public opinions on complex, value-laden topics to develop recommendations and policies for a larger community.17 The goal is to find collective solutions to challenging social problems. DD achieves this by giving participants an opportunity to explore a topic in-depth, question experts, and engage peers in reason-based discussions.18,19 This method has its roots in political science and has been used over several decades to successfully inform policy making on a broad array of topics nationally and internationally—from health research ethics in the US to nuclear and energy policy in Japan.7,16,20,21 DD has been found to promote ownership of public programs and lend legitimacy to policy decisions, political institutions, and democracy itself.18

A single day (8 hours) DD session was convened, following a Citizens Jury model of deliberation, which brings veteran patients together to learn about a topic, ask questions of experts, deliberate with peers, and generate a “citizen’s report” that contains a set of recommendations (Table 1). An overview of the different models of DD and rationale for each can be found elsewhere.8,15

Recruitment Considerations

A purposively selected sample of civilian care-eligible veterans from a midwestern VHA health care system (1 medical center and 3 community-based outpatient clinics [CBOCs]) were invited to the DD session. The targeted number of participants was 30. Female veterans, who comprise only 7% of the local veteran population, were oversampled to account for their potentially different health care needs and to create balance between males and females in the session. Oversampling for other characteristics was not possible due to the relatively small sample size. Based on prior experience,7 it was assumed that 70% of willing participants would attend the session; therefore 34 veterans were invited and 24 attended. Each participant received a $200 incentive in appreciation for their substantial time commitment and to offset transportation costs.

Background Materials

A packet with educational materials (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 10.5) was mailed to participants about 2 weeks before the DD session. Participants were asked to review prior to attending the session. These materials described the session (eg, purpose, organizers, importance) and provided factual information about the Choice Act (eg, eligibility, out-of-pocket costs, travel pay, prescription drug policies).

Session Overview

The session was structured to accomplish the following goals: (1) Elicit participants’ opinions about access to health care and reasons for those opinions; (2) Provide in-depth education about the Choice Act through presentations and discussions with topical experts; and (3) Elicit reasoning and recommendations on both the criteria by which participants prioritize candidates for civilian care and how participants would allocate additional funding to improve access (ie, by building VHA capacity to deliver more timely health care vs purchasing health care from civilian HCPs).

Participants were asked to fill out a survey on arrival in the morning and were assigned to 1 of 3 tables or small groups. Each table had a facilitator who had extensive experience in qualitative data collection methods and guided the dialogue using a scripted protocol that they helped develop and refine. The facilitation materials drew from and used previously published studies.22,23 Each facilitator audio recorded the sessions and took notes. Three experts presented during plenary education sessions. Presentations were designed to provide balanced factual information and included a veteran’s perspective. One presenter was a clinician on the project team, another was a local clinical leader responsible for making decisions about what services to provide via civilian care (buy) vs enhancing the local VHA health system’s ability to provide those services (build), and the third presenter was a veteran who was on the project team.

Education Session 1

The first plenary education session with expert presentations was conducted after each table completed an icebreaker exercise. The project team physician provided a brief history and description of the Choice Act to reinforce educational materials sent to participants prior to the session. The health system clinical leader described his decision process and principles and highlighted constraints placed on him by the Choice Act that were in place at the time of the DD session. He also described existing local and national programs to provide civilian care (eg, local fee-basis non-VHA care programs) and how these programs sought to achieve goals similar to the Choice Act. The veteran presenter focused on the importance of session participants providing candid insight and observations and emphasized that this session was a significant opportunity to “have their voices heard.”

Deliberation 1: What criteria should be used to prioritize patients for receiving civilian care paid for by the VHA? To elicit preferences on the central question of this deliberation, participants were presented with 8 real-world cases that were based on interviews conducted with Choice Act-eligible veterans (Table 2 and eAppendices A

Education Session 2

In the second plenary session, the project team physician provided information about health care access issues, both inside and outside of the VHA, particularly between urban and rural areas. He also discussed factors related to the insufficient capacity to meet growing demand that contributed to the VHA wait-time crisis. The veteran presenter shared reflections on health care access from a veteran’s perspective.

Deliberation 2: How should additional funding be divided between increasing the ability of the VHA to (1) provide care by VHA HCPs; and (2) pay for care from non-VHA civilian HCPs? Participants were presented the patient examples and Choice Act funding scenarios (the buy policy option) and contrasted that with a build policy option. Participants were explicitly encouraged to shift their perspectives from thinking about individual cases to considering policy-level decisions and the broader social good (Table 2).

Ensuring Robust Deliberations

If participants do not adequately grasp the complexities of the topic, a deliberation can fail. To facilitate nuanced reasoning, real-world concrete examples were developed as the starting point of each deliberation based on interviews with actual patients (deliberation 1) and actual policy proposals relevant to the funding allocation decisions within the Choice Act (deliberation 2).

A deliberation also can fail with self-silencing, where participants withhold opinions that differ from those articulated first or by more vocal members of the group.24 To combat self-silencing, highly experienced facilitators were used to ensure sharing from all participants and to support an open-minded, courteous, and reason-based environment for discourse. It was specified that the best solutions are achieved through reason-based and cordial disagreement and that success can be undermined when participants simply agree because it is easier or more comfortable.

A third way a deliberation can fail is if individuals do not adopt a group or system-level perspective. To counter this, facilitators reinforced at multiple points the importance of taking a broader social perspective rather than sharing only one’s personal preferences.

Finally, it is important to assess the quality of the deliberative process itself, to ensure that results are trustworthy.25 To assess the quality of the deliberative process, participants knowledge about key issues pre- and postdeliberation were assessed. Participants also were asked to rate the quality of the facilitators and how well they felt their voice was heard and respected, and facilitators made qualitative assessments about the extent to which participants were engaged in reason-based and collaborative discussion.

Data

Quantitative data were collected via pre- and postsession surveys. The surveys contained items related to knowledge about the Choice Act, expectations for the DD session, beliefs and opinions about the provision of health care for veterans, recommended funding allocations between build vs buy policy options, and general demographics. Qualitative data were collected through detailed notes taken by the 3 facilitators. Each table’s deliberations were audio recorded so that gaps in the notes could be filled.

The 3 facilitators, who were all experienced qualitative researchers, typed their written notes into a template immediately after the session. Two of the 3 facilitators led the analysis of the session notes. Findings within and across the 3 deliberation tables were developed using content and matrix analysis methods.26 Descriptive statistics were generated from survey responses and compared survey items pre- and postsession using paired t tests or χ2 tests for categorical responses.

Results

Thirty-three percent of individuals invited (n = 127) agreed to participate. Those who declined cited conflicts related to distance, transportation, work/school, medical appointments, family commitments, or were not interested. In all, 24 (69%) of the 35 veterans who accepted the invitation attended the deliberation session. Of the 11 who accepted but did not attend, 5 cancelled ahead of time because of conflicts (Figure). Most participants were male (70%), 48% were aged 61 to 75 years, 65% were white, 43% had some college education, 43% reported an annual income of between $25,000 and $40,000, and only 35% reported very good health (eAppendix D).

Deliberation 1

During the deliberation on the prioritization criteria, the concept of “condition severity” emerged as an important criterion for veterans. This criterion captured simultaneous consideration of both clinical necessity and burden on the veteran to obtain care. For example, participants felt that patients with a life-threatening illness should be prioritized for civilian care over patients who need preventative or primary care (clinical necessity) and that elderly patients with substantial difficulty traveling to VHA appointments should be prioritized over patients who can travel more easily (burden). The Choice Act regulations at the time of the DD session did not reflect this nuanced perspective, stipulating only that veterans must live > 40 miles from the nearest VHA medical facility.

One of the 3 groups did not prioritize the patient cases because some members felt that no veteran should be constrained from receiving civilian care if they desired it. Nonetheless, this group did agree with prioritizing the first 2 cases in Table 3. The other groups prioritized all 8 cases in generally similar ways.

Deliberation 2

No clear consensus emerged on the buy vs build question. A representative from each table presented their group’s positions, rationale, and recommendations after deliberations were completed. After hearing the range of positions, the groups then had another opportunity to deliberate based on what they heard from the other tables; no new recommendations or consensus emerged.

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the build policy offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) increase access for rural veterans by building CBOCs and deploying more mobile units that could bring outlets for health care closer to their home communities; (2) provide critical and unique medical expertise to address veteran-specific issues such as prosthetics, traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, spinal cord injury, and shrapnel wounds that are typically not available through civilian providers; (3) give VHA more oversight over the quality and cost of care, which is more challenging to do with civilian providers; and (4) Improve VHA infrastructure by, for example, upgrading technology and attracting the best clinicians and staff to support “our VHA.”

Participants who were in favor of allocating more funds toward the buy policy also offered a range of rationales, saying that it would (1) decrease patient burden by increasing access through community providers, decreasing wait time, and lessening personal cost and travel time; (2) allow more patients to receive civilian care, which was generally seen as beneficial by a few participants because of perceptions that the VHA provides lower quality care due to a shortage of VHA providers, run-down/older facilities, lack of technology, and poorer-quality VHA providers; and (3) provide an opportunity to divest of costly facilities and invest in other innovative approaches. Regarding this last reason, a few participants felt that the VHA is “gouged” when building medical centers that overrun budgets. They also were concerned that investing in facilities tied VHA to specific locations when current locations of veterans may change “25 years from now.”

Survey Results

Twenty-three of the 24 participants completed both pre- and postsession surveys. The majority of participants in the session felt people in the group respected their opinion (96%); felt that the facilitator did not try to influence the group with her own opinions (96%); indicated they understood the information enough to participate as much as they wanted (100%); and were hopeful that their reasoning and recommendations would help inform VHA policy makers (82%).

The surveys also provided an opportunity to examine the extent to which knowledge, attitudes, and opinions changed from before to after the deliberation. Even with the small sample, responses revealed a trend toward improved knowledge about key elements of the Choice Act and its goals. Further, there was a shift in some participants’ opinions about how patients should be prioritized to receive civilian care. For example, before the deliberation participants generally felt that all veterans should be able to receive civilian care, whereas postdeliberation this was not the case. Postdeliberation, most participants felt that primary care should not be a high priority for civilian care but continued to endorse prioritizing civilian care for specialty services like orthopedic or cardiology-related care. Finally, participants moved from more diverse recommendations regarding additional funds allocations, toward consensus after the deliberation around allocating funds to the build policy. Eight participants supported a build policy beforehand, whereas 16 supported this policy afterward.

Discussion

This study explored DD as a method for deeply engaging veterans in complex policy making to guide funding allocation and prioritization decisions related to the Choice Act, decisions that are still very relevant today within the context of the Mission Act and have substantial implications for how health care is delivered in the VHA. The Mission Act passed on June 6, 2018, with the goal of improving access to and the reliability of civilian or community care for eligible veterans.27 Decisions related to appropriating scarce funding to improve access to care is an emotional and value-laden topic that elicited strong and divergent opinions among the participants. Veterans were eager to have their voices heard and had strong expectations that VHA leadership would be briefed about their recommendations. The majority of participants were satisfied with the deliberation process, felt they understood the issues, and felt their opinions were respected. They expressed feelings of comradery and community throughout the process.

In this single deliberation session, the groups did not achieve a single, final consensus regarding how VHA funding should ultimately be allocated between buy and build policy options. Nonetheless, participants provided a rich array of recommendations and rationale for them. Session moderators observed rich, sophisticated, fair, and reason-based discussions on this complex topic. Participants left with a deeper knowledge and appreciation for the complex trade-offs and expressed strong rationales for both sides of the policy debate on build vs buy. In addition, the project yielded results of high interest to VHA policy makers.

This work was presented in multiple venues between 2015 to 2016, and to both local and national VHA leadership, including the local Executive Quality Leadership Boards, the VHA Central Office Committee on the Future State of VA Community Care, the VA Office of Patient Centered Care, and the National Veteran Experience Committee. Through these discussions and others, we saw great interest within the VHA system and high-level leaders to explore ways to include veterans’ voices in the policy-making process. This work was invaluable to our research team (eAppendix E

Many health system decisions regarding what care should be delivered (and how) involve making difficult, value-laden choices in the context of limited resources. DD methods can be used to target and obtain specific viewpoints from diverse populations, such as the informed perspectives of minority and underrepresented populations within the VHA.19 For example, female veterans were oversampled to ensure that the informed preferences of this population was obtained. Thus, DD methods could provide a valuable tool for health systems to elicit in-depth diverse patient input on high-profile policies that will have a substantial impact on the system’s patient population.

Limitations

One potential downside of DD is that, because of the resource-intensive nature of deliberation sessions, they are often conducted with relatively small groups.9 Viewpoints of those within these small samples who are willing to spend an entire day discussing a complex topic may not be representative of the larger patient community. However, the core goal of DD is diversity of opinions rather than representativeness.

A stratified random sampling strategy that oversampled for underrepresented and minority populations was used to help select a diverse group that represents the population on key characteristics and partially addresses concern about representativeness. Efforts to optimize participation rates, including providing monetary incentives, also are helpful and have led to high participation rates in past deliberations.7

Health system communication strategies that promote the importance of becoming involved in DD sessions also may be helpful in improving rates of recruitment. On particularly important topics where health system leaders feel a larger resource investment is justified, conducting larger scale deliberations with many small groups may obtain more generalizable evidence about what individual patients and groups of patients recommend.7 However, due to the inherent limitations of surveys and focus group approaches for obtaining informed views on complex topics, there are no clear systematic alternatives to the DD approach.

Conclusion