User login

Making social media work for your practice

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.

Sixth, thoroughly vet all content that you share. Avoid automatically sharing articles or posts because of a catchy headline. Read them before you post them. There may be details buried in them that are not credible or with which you do not agree.

Seventh, build community by connecting and engaging with other users on your social media platform(s) of choice.

Eighth, integrate multiple media (i.e., photos, videos, infographics) and/or social media platforms (i.e., embed link to YouTube or a website) to increase engagement.

Ninth, adhere to the code of ethics, governance, and privacy of the profession and of your employer.

Best practices: Privacy and governance in patient-oriented communication on social media

Two factors that have been of pivotal concern with the adoption of social media in the health care arena and led to many health care professionals being laggards as opposed to early adopters are privacy and governance. Will it violate the patient–provider relationship? What about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act? How do I maintain boundaries between myself and the public at large? These are just a few of the questions that commonly are asked by those who are unfamiliar with social media etiquette for health care professionals. We highly recommend reviewing the position paper regarding online medical professionalism issued by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards as a starting point.13 We believe the following to be contemporary guiding principles for GI health providers for maintaining a digital footprint on social media that reflects the ethical and professional standards of the field.

First, avoid sharing information that could be construed as a patient identifier without documented consent. This includes, but is not limited to, an identifiable specimen or photograph, and stories of care, rare conditions, and complications. Note that dates and location of care can lead to identification of a patient or care episode.

Second, recognize that personal and professional online profiles/pages are discoverable. Many advocate for separating the two as a means of shielding the public from elements of a private persona (i.e., family pictures and controversial opinions). However, the capacity to share and find comments and images on social media is much more powerful than the privacy settings on the various social media platforms. If you establish distinct personal and professional profiles, exercise caution before accepting friend or follow requests from patients on your personal profile. In addition, be cautious with your posts on private social media accounts because they rarely truly are private.

Third, avoid providing specific medical recommendations to individuals. This creates a patient–provider relationship and legal duty. Instead, recommend consultation with a health care provider and consider providing a link to general information on the topic (e.g., AGA information for patients at www.gastro.org/patientinfo).

Fourth, declare conflicts of interest, if applicable, when sharing information involving your clinical, research, and/or business practice.

Fifth, routinely monitor your online presence for accuracy and appropriateness of content posted by you and by others in reference to you. Know that our profession’s ethical standards for behavior extend to social media and we can be held accountable to colleagues and our employer if we violate them.

Many employers have become savvy to issues of governance in use of social media and institute policy recommendations to which employees are expected to adhere. If you are an employee, we recommend checking with your marketing and/or human resources department(s) in regards to this. If you are an employer and do not have such a policy on online professionalism, it is our hope that this article serves as a launching pad.

Novel applications for social media in clinical practice

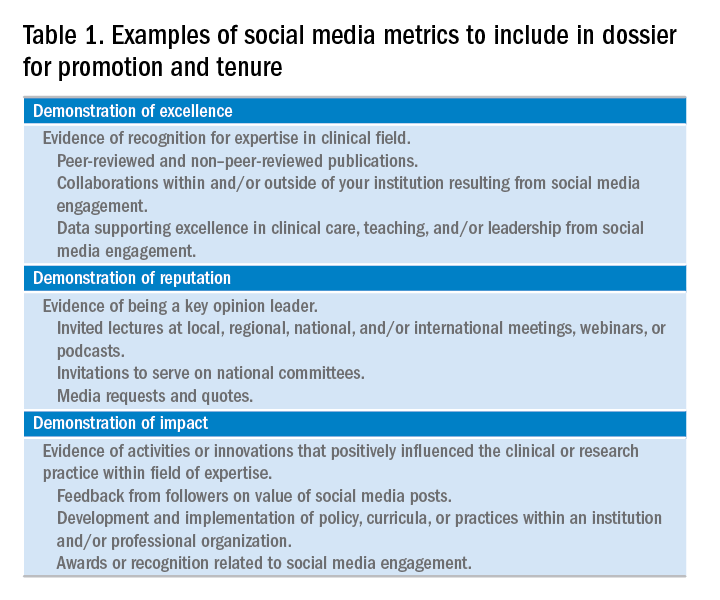

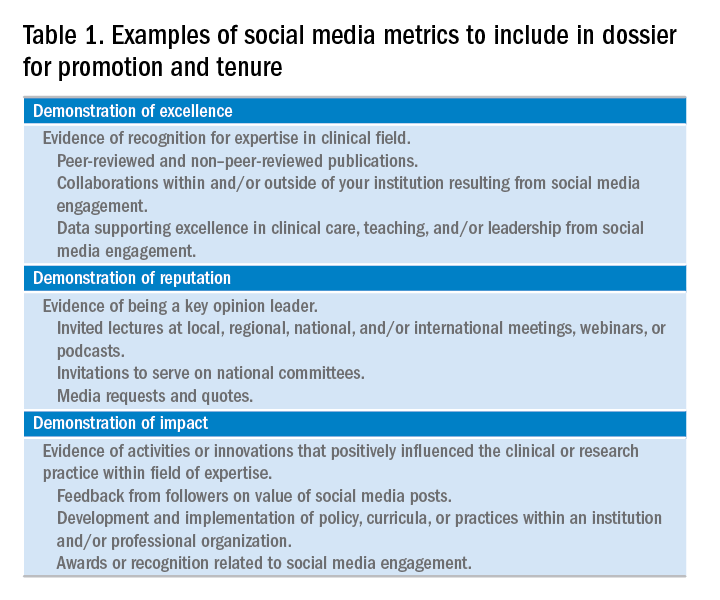

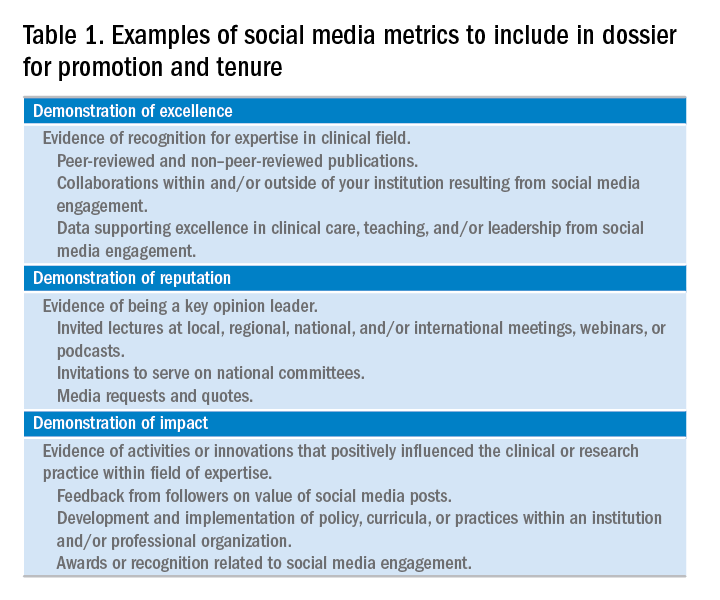

Social media has been shown to be an effective medium for medical education through virtual journal clubs, moderated discussions or chats, and video sharing for teaching procedures, to name a few applications. Social media is used to collect data via polls or surveys, and to disseminate and track the views and downloads of published works. It is also a source for unsolicited, real-time feedback on patient experience and engagement through data-mining techniques, such as natural language processing and, more simply, for solicited feedback for patient satisfaction ratings. However, its role in academic promotion is less clear and is an area for which we see a great opportunity for growth.

Summary

We have outlined a high-level overview for why you should consider establishing and maintaining a professional presence on social media and how to accomplish this. These reasons include sharing information with colleagues, patients, and the public; amplifying the voice of physicians, a view that has diminished in the often-volatile health care environment; and promotion of the value of your work, be it patient care, advocacy, research, or education. You will have a smoother experience if you learn your local rules and policies and abide by our suggestions to avoid adverse outcomes. You will be most effective if you establish goals for your social media participation and revisit these goals over time for continued relevance and success and if you have consistent and valuable output that will support attainment of these goals. Welcome to the GI social media community! Be sure to follow Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the American Gastroenterological Association on Facebook (facebook.com/cghjournal and facebook.com/amergastroassn) and Twitter (@AGA_CGH and @AmerGastroAssn), and the coauthors (@DMGrayMD and @DrDeborahFisher) on Twitter.

References

1. Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center [updated January 12, 2017]. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

2. Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-24.

3. Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

4. Chou W.Y., Hunt Y.M., Beckjord E.B. et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48.

5. Chretien K.C., Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;27:1413-21.

6. Social Media ‘likes’ Healthcare. PwC Health Research Institute; 2012. Available from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/publications/pdf/health-care-social-media-report.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

7. Griffis H.M., Kilaru A.S., Werner R.M., et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264.

8. Davis E.D., Tang S.J., Glover P.H., et al. Impact of social media on gastroenterologists in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:258-9.

9. Chiang A.L., Vartabedian B., Spiegel B. Harnessing the hashtag: a standard approach to GI dialogue on social media. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1082-4.

10. Reich J., Guo L., Hall J., et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2678-87.

11. Timms C., Forton D.M., Poullis A. Social media use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Med. 2014;14:215.

12. Prasad B. Social media, health care, and social networking. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:492-5.

13. Farnan J.M., Snyder Sulmasy L., Worster B.K., et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:620-7.

14. Cabrera D., Vartabedian B.S., Spinner R.J., et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421-5.

15. Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic includes social media scholarship activities in academic advancement. Available from https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/

Date: May 26, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

16. Freitag C.E., Arnold M.A., Gardner J.M., et al. If you are not on social media, here’s what you’re missing! #DoTheThing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; (Epub ahead of print).

17. Stukus D.R. How I used twitter to get promoted in academic medicine. Available from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2016/10/used-twitter-get-promoted-academic-medicine.html. Date: October 9, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

Dr. Gray is in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus; Dr. Fisher is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.

Sixth, thoroughly vet all content that you share. Avoid automatically sharing articles or posts because of a catchy headline. Read them before you post them. There may be details buried in them that are not credible or with which you do not agree.

Seventh, build community by connecting and engaging with other users on your social media platform(s) of choice.

Eighth, integrate multiple media (i.e., photos, videos, infographics) and/or social media platforms (i.e., embed link to YouTube or a website) to increase engagement.

Ninth, adhere to the code of ethics, governance, and privacy of the profession and of your employer.

Best practices: Privacy and governance in patient-oriented communication on social media

Two factors that have been of pivotal concern with the adoption of social media in the health care arena and led to many health care professionals being laggards as opposed to early adopters are privacy and governance. Will it violate the patient–provider relationship? What about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act? How do I maintain boundaries between myself and the public at large? These are just a few of the questions that commonly are asked by those who are unfamiliar with social media etiquette for health care professionals. We highly recommend reviewing the position paper regarding online medical professionalism issued by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards as a starting point.13 We believe the following to be contemporary guiding principles for GI health providers for maintaining a digital footprint on social media that reflects the ethical and professional standards of the field.

First, avoid sharing information that could be construed as a patient identifier without documented consent. This includes, but is not limited to, an identifiable specimen or photograph, and stories of care, rare conditions, and complications. Note that dates and location of care can lead to identification of a patient or care episode.

Second, recognize that personal and professional online profiles/pages are discoverable. Many advocate for separating the two as a means of shielding the public from elements of a private persona (i.e., family pictures and controversial opinions). However, the capacity to share and find comments and images on social media is much more powerful than the privacy settings on the various social media platforms. If you establish distinct personal and professional profiles, exercise caution before accepting friend or follow requests from patients on your personal profile. In addition, be cautious with your posts on private social media accounts because they rarely truly are private.

Third, avoid providing specific medical recommendations to individuals. This creates a patient–provider relationship and legal duty. Instead, recommend consultation with a health care provider and consider providing a link to general information on the topic (e.g., AGA information for patients at www.gastro.org/patientinfo).

Fourth, declare conflicts of interest, if applicable, when sharing information involving your clinical, research, and/or business practice.

Fifth, routinely monitor your online presence for accuracy and appropriateness of content posted by you and by others in reference to you. Know that our profession’s ethical standards for behavior extend to social media and we can be held accountable to colleagues and our employer if we violate them.

Many employers have become savvy to issues of governance in use of social media and institute policy recommendations to which employees are expected to adhere. If you are an employee, we recommend checking with your marketing and/or human resources department(s) in regards to this. If you are an employer and do not have such a policy on online professionalism, it is our hope that this article serves as a launching pad.

Novel applications for social media in clinical practice

Social media has been shown to be an effective medium for medical education through virtual journal clubs, moderated discussions or chats, and video sharing for teaching procedures, to name a few applications. Social media is used to collect data via polls or surveys, and to disseminate and track the views and downloads of published works. It is also a source for unsolicited, real-time feedback on patient experience and engagement through data-mining techniques, such as natural language processing and, more simply, for solicited feedback for patient satisfaction ratings. However, its role in academic promotion is less clear and is an area for which we see a great opportunity for growth.

Summary

We have outlined a high-level overview for why you should consider establishing and maintaining a professional presence on social media and how to accomplish this. These reasons include sharing information with colleagues, patients, and the public; amplifying the voice of physicians, a view that has diminished in the often-volatile health care environment; and promotion of the value of your work, be it patient care, advocacy, research, or education. You will have a smoother experience if you learn your local rules and policies and abide by our suggestions to avoid adverse outcomes. You will be most effective if you establish goals for your social media participation and revisit these goals over time for continued relevance and success and if you have consistent and valuable output that will support attainment of these goals. Welcome to the GI social media community! Be sure to follow Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the American Gastroenterological Association on Facebook (facebook.com/cghjournal and facebook.com/amergastroassn) and Twitter (@AGA_CGH and @AmerGastroAssn), and the coauthors (@DMGrayMD and @DrDeborahFisher) on Twitter.

References

1. Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center [updated January 12, 2017]. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

2. Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-24.

3. Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

4. Chou W.Y., Hunt Y.M., Beckjord E.B. et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48.

5. Chretien K.C., Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;27:1413-21.

6. Social Media ‘likes’ Healthcare. PwC Health Research Institute; 2012. Available from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/publications/pdf/health-care-social-media-report.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

7. Griffis H.M., Kilaru A.S., Werner R.M., et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264.

8. Davis E.D., Tang S.J., Glover P.H., et al. Impact of social media on gastroenterologists in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:258-9.

9. Chiang A.L., Vartabedian B., Spiegel B. Harnessing the hashtag: a standard approach to GI dialogue on social media. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1082-4.

10. Reich J., Guo L., Hall J., et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2678-87.

11. Timms C., Forton D.M., Poullis A. Social media use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Med. 2014;14:215.

12. Prasad B. Social media, health care, and social networking. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:492-5.

13. Farnan J.M., Snyder Sulmasy L., Worster B.K., et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:620-7.

14. Cabrera D., Vartabedian B.S., Spinner R.J., et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421-5.

15. Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic includes social media scholarship activities in academic advancement. Available from https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/

Date: May 26, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

16. Freitag C.E., Arnold M.A., Gardner J.M., et al. If you are not on social media, here’s what you’re missing! #DoTheThing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; (Epub ahead of print).

17. Stukus D.R. How I used twitter to get promoted in academic medicine. Available from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2016/10/used-twitter-get-promoted-academic-medicine.html. Date: October 9, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

Dr. Gray is in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus; Dr. Fisher is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.

Sixth, thoroughly vet all content that you share. Avoid automatically sharing articles or posts because of a catchy headline. Read them before you post them. There may be details buried in them that are not credible or with which you do not agree.

Seventh, build community by connecting and engaging with other users on your social media platform(s) of choice.

Eighth, integrate multiple media (i.e., photos, videos, infographics) and/or social media platforms (i.e., embed link to YouTube or a website) to increase engagement.

Ninth, adhere to the code of ethics, governance, and privacy of the profession and of your employer.

Best practices: Privacy and governance in patient-oriented communication on social media

Two factors that have been of pivotal concern with the adoption of social media in the health care arena and led to many health care professionals being laggards as opposed to early adopters are privacy and governance. Will it violate the patient–provider relationship? What about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act? How do I maintain boundaries between myself and the public at large? These are just a few of the questions that commonly are asked by those who are unfamiliar with social media etiquette for health care professionals. We highly recommend reviewing the position paper regarding online medical professionalism issued by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards as a starting point.13 We believe the following to be contemporary guiding principles for GI health providers for maintaining a digital footprint on social media that reflects the ethical and professional standards of the field.

First, avoid sharing information that could be construed as a patient identifier without documented consent. This includes, but is not limited to, an identifiable specimen or photograph, and stories of care, rare conditions, and complications. Note that dates and location of care can lead to identification of a patient or care episode.

Second, recognize that personal and professional online profiles/pages are discoverable. Many advocate for separating the two as a means of shielding the public from elements of a private persona (i.e., family pictures and controversial opinions). However, the capacity to share and find comments and images on social media is much more powerful than the privacy settings on the various social media platforms. If you establish distinct personal and professional profiles, exercise caution before accepting friend or follow requests from patients on your personal profile. In addition, be cautious with your posts on private social media accounts because they rarely truly are private.

Third, avoid providing specific medical recommendations to individuals. This creates a patient–provider relationship and legal duty. Instead, recommend consultation with a health care provider and consider providing a link to general information on the topic (e.g., AGA information for patients at www.gastro.org/patientinfo).

Fourth, declare conflicts of interest, if applicable, when sharing information involving your clinical, research, and/or business practice.

Fifth, routinely monitor your online presence for accuracy and appropriateness of content posted by you and by others in reference to you. Know that our profession’s ethical standards for behavior extend to social media and we can be held accountable to colleagues and our employer if we violate them.

Many employers have become savvy to issues of governance in use of social media and institute policy recommendations to which employees are expected to adhere. If you are an employee, we recommend checking with your marketing and/or human resources department(s) in regards to this. If you are an employer and do not have such a policy on online professionalism, it is our hope that this article serves as a launching pad.

Novel applications for social media in clinical practice

Social media has been shown to be an effective medium for medical education through virtual journal clubs, moderated discussions or chats, and video sharing for teaching procedures, to name a few applications. Social media is used to collect data via polls or surveys, and to disseminate and track the views and downloads of published works. It is also a source for unsolicited, real-time feedback on patient experience and engagement through data-mining techniques, such as natural language processing and, more simply, for solicited feedback for patient satisfaction ratings. However, its role in academic promotion is less clear and is an area for which we see a great opportunity for growth.

Summary

We have outlined a high-level overview for why you should consider establishing and maintaining a professional presence on social media and how to accomplish this. These reasons include sharing information with colleagues, patients, and the public; amplifying the voice of physicians, a view that has diminished in the often-volatile health care environment; and promotion of the value of your work, be it patient care, advocacy, research, or education. You will have a smoother experience if you learn your local rules and policies and abide by our suggestions to avoid adverse outcomes. You will be most effective if you establish goals for your social media participation and revisit these goals over time for continued relevance and success and if you have consistent and valuable output that will support attainment of these goals. Welcome to the GI social media community! Be sure to follow Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the American Gastroenterological Association on Facebook (facebook.com/cghjournal and facebook.com/amergastroassn) and Twitter (@AGA_CGH and @AmerGastroAssn), and the coauthors (@DMGrayMD and @DrDeborahFisher) on Twitter.

References

1. Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center [updated January 12, 2017]. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

2. Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-24.

3. Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

4. Chou W.Y., Hunt Y.M., Beckjord E.B. et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48.

5. Chretien K.C., Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;27:1413-21.

6. Social Media ‘likes’ Healthcare. PwC Health Research Institute; 2012. Available from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/publications/pdf/health-care-social-media-report.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

7. Griffis H.M., Kilaru A.S., Werner R.M., et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264.

8. Davis E.D., Tang S.J., Glover P.H., et al. Impact of social media on gastroenterologists in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:258-9.

9. Chiang A.L., Vartabedian B., Spiegel B. Harnessing the hashtag: a standard approach to GI dialogue on social media. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1082-4.

10. Reich J., Guo L., Hall J., et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2678-87.

11. Timms C., Forton D.M., Poullis A. Social media use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Med. 2014;14:215.

12. Prasad B. Social media, health care, and social networking. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:492-5.

13. Farnan J.M., Snyder Sulmasy L., Worster B.K., et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:620-7.

14. Cabrera D., Vartabedian B.S., Spinner R.J., et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421-5.

15. Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic includes social media scholarship activities in academic advancement. Available from https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/

Date: May 26, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

16. Freitag C.E., Arnold M.A., Gardner J.M., et al. If you are not on social media, here’s what you’re missing! #DoTheThing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; (Epub ahead of print).

17. Stukus D.R. How I used twitter to get promoted in academic medicine. Available from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2016/10/used-twitter-get-promoted-academic-medicine.html. Date: October 9, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

Dr. Gray is in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus; Dr. Fisher is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.