User login

How well are we doing with adolescent vaccination?

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

When the public misplaces their trust

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

COVID-19 vaccination recap: The latest developments

In recent weeks, the COVID-19 vaccine arsenal has grown more robust. Here’s what you need to know:

Variant-specific boosters. On September 1, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) adopted a recommendation for a booster of either a new bivalent Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 12 years and older) or bivalent Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 18 years and older) at least 2 months after receipt of a primary series or prior monovalent booster dose. Both bivalent vaccines were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and offer protection against one of the more common circulating strains of SARS-COV-2 (BA.1) while boosting immunity to the original strain. Both options are approved only as booster shots, not as an original COVID vaccine series.1

Novavax vaccine. This summer, the FDA issued an EUA for the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine in adults and a later EUA for adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years).2 Novavax is the fourth vaccine available to combat COVID-19 infection. This newest addition to the COVID armamentarium consists of coronavirus protein subunits, produced using recombinant technology, and a matrix adjuvant. The primary series consists of 2 doses administered at least 3 weeks apart.3,4

A few caveats: The Novavax vaccine comes in 10-dose vials, which should be kept refrigerated until use. Once the first dose is used, the vial should be discarded after 6 hours. This may present some scheduling and logistical issues. Also, the Novavax vaccine is not currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, or as a booster to other vaccines.3,4

The effectiveness and safety of the Novavax vaccine appears to be comparable to that of the other vaccines approved to date, although measuring vaccine effectiveness is a tricky business given the rapid mutation of the virus and changing dominant strains.3,4 The Novavax vaccine’s efficacy against currently circulating Omicron variants of the virus (eg, BA.2.12.1, BA.4, BA.5) remains to be determined.

As far as safety, preliminary studies indicate that Novavax may be associated with rare cases of myocarditis.3,4 Myocarditis can result from the COVID infection itself at an overall rate of 1 to 2 per 1000, which is 16 times the rate in adults without COVID.5

Could it provide reassurance to the hesitant? The Novavax COVID vaccine was developed using a vaccine platform and production process similar to that of other commonly administered vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine and human papillomavirus vaccine. This may make it an appealing option for patients who have shown hesitancy toward new vaccine technologies.

And, of course, there are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Currently, there are 2 vaccines approved under the normal licensing process for adults, both of which are mRNA-based vaccines: Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty) for those ages 12 years and older and Moderna (Spikevax) for those ages 18 and older. A third COVID vaccine option is manufactured by Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) and uses an adenovirus platform. The FDA revised its EUA in May to limit its use.6 The Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been associated with rare but serious reactions called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia. ACIP recommends all other vaccines in preference to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

For more on COVID vaccination for patients of all ages, see: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

1. Oliver S. Evidence to recommendations framework: Bivalent COVID-19 vaccine booster doses. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 1, 2002. Accessed September 6, 2002. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-09-01/08-COVID-Oliver-508.pdf

2. FDA. Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-adjuvanted

3. Dubovsky F. NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax COVID-19 vaccine) in adults (≥ 18 years of age). Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/04-covid-dubovsky-508.pdf

4. Twentyman E. Evidence to recommendation framework: Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted in adults ages 18 years and older. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/05-covid-twentyman-508.pdf

5. Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, et al. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data—United States, March 2020–January 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1228-1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5

6. American Hospital Association. FDA limits J&J COVID-19 vaccine use to certain adults. Published May 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. www.aha.org/news/headline/2022-05-06-fda-limits-jj-covid-19-vaccine-use-certain-adults

In recent weeks, the COVID-19 vaccine arsenal has grown more robust. Here’s what you need to know:

Variant-specific boosters. On September 1, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) adopted a recommendation for a booster of either a new bivalent Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 12 years and older) or bivalent Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 18 years and older) at least 2 months after receipt of a primary series or prior monovalent booster dose. Both bivalent vaccines were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and offer protection against one of the more common circulating strains of SARS-COV-2 (BA.1) while boosting immunity to the original strain. Both options are approved only as booster shots, not as an original COVID vaccine series.1

Novavax vaccine. This summer, the FDA issued an EUA for the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine in adults and a later EUA for adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years).2 Novavax is the fourth vaccine available to combat COVID-19 infection. This newest addition to the COVID armamentarium consists of coronavirus protein subunits, produced using recombinant technology, and a matrix adjuvant. The primary series consists of 2 doses administered at least 3 weeks apart.3,4

A few caveats: The Novavax vaccine comes in 10-dose vials, which should be kept refrigerated until use. Once the first dose is used, the vial should be discarded after 6 hours. This may present some scheduling and logistical issues. Also, the Novavax vaccine is not currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, or as a booster to other vaccines.3,4

The effectiveness and safety of the Novavax vaccine appears to be comparable to that of the other vaccines approved to date, although measuring vaccine effectiveness is a tricky business given the rapid mutation of the virus and changing dominant strains.3,4 The Novavax vaccine’s efficacy against currently circulating Omicron variants of the virus (eg, BA.2.12.1, BA.4, BA.5) remains to be determined.

As far as safety, preliminary studies indicate that Novavax may be associated with rare cases of myocarditis.3,4 Myocarditis can result from the COVID infection itself at an overall rate of 1 to 2 per 1000, which is 16 times the rate in adults without COVID.5

Could it provide reassurance to the hesitant? The Novavax COVID vaccine was developed using a vaccine platform and production process similar to that of other commonly administered vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine and human papillomavirus vaccine. This may make it an appealing option for patients who have shown hesitancy toward new vaccine technologies.

And, of course, there are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Currently, there are 2 vaccines approved under the normal licensing process for adults, both of which are mRNA-based vaccines: Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty) for those ages 12 years and older and Moderna (Spikevax) for those ages 18 and older. A third COVID vaccine option is manufactured by Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) and uses an adenovirus platform. The FDA revised its EUA in May to limit its use.6 The Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been associated with rare but serious reactions called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia. ACIP recommends all other vaccines in preference to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

For more on COVID vaccination for patients of all ages, see: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

In recent weeks, the COVID-19 vaccine arsenal has grown more robust. Here’s what you need to know:

Variant-specific boosters. On September 1, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) adopted a recommendation for a booster of either a new bivalent Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 12 years and older) or bivalent Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (for individuals ages 18 years and older) at least 2 months after receipt of a primary series or prior monovalent booster dose. Both bivalent vaccines were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and offer protection against one of the more common circulating strains of SARS-COV-2 (BA.1) while boosting immunity to the original strain. Both options are approved only as booster shots, not as an original COVID vaccine series.1

Novavax vaccine. This summer, the FDA issued an EUA for the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine in adults and a later EUA for adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years).2 Novavax is the fourth vaccine available to combat COVID-19 infection. This newest addition to the COVID armamentarium consists of coronavirus protein subunits, produced using recombinant technology, and a matrix adjuvant. The primary series consists of 2 doses administered at least 3 weeks apart.3,4

A few caveats: The Novavax vaccine comes in 10-dose vials, which should be kept refrigerated until use. Once the first dose is used, the vial should be discarded after 6 hours. This may present some scheduling and logistical issues. Also, the Novavax vaccine is not currently approved for use in children younger than 12 years, or as a booster to other vaccines.3,4

The effectiveness and safety of the Novavax vaccine appears to be comparable to that of the other vaccines approved to date, although measuring vaccine effectiveness is a tricky business given the rapid mutation of the virus and changing dominant strains.3,4 The Novavax vaccine’s efficacy against currently circulating Omicron variants of the virus (eg, BA.2.12.1, BA.4, BA.5) remains to be determined.

As far as safety, preliminary studies indicate that Novavax may be associated with rare cases of myocarditis.3,4 Myocarditis can result from the COVID infection itself at an overall rate of 1 to 2 per 1000, which is 16 times the rate in adults without COVID.5

Could it provide reassurance to the hesitant? The Novavax COVID vaccine was developed using a vaccine platform and production process similar to that of other commonly administered vaccines, such as hepatitis B vaccine and human papillomavirus vaccine. This may make it an appealing option for patients who have shown hesitancy toward new vaccine technologies.

And, of course, there are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Currently, there are 2 vaccines approved under the normal licensing process for adults, both of which are mRNA-based vaccines: Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty) for those ages 12 years and older and Moderna (Spikevax) for those ages 18 and older. A third COVID vaccine option is manufactured by Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) and uses an adenovirus platform. The FDA revised its EUA in May to limit its use.6 The Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been associated with rare but serious reactions called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia. ACIP recommends all other vaccines in preference to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

For more on COVID vaccination for patients of all ages, see: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

1. Oliver S. Evidence to recommendations framework: Bivalent COVID-19 vaccine booster doses. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 1, 2002. Accessed September 6, 2002. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-09-01/08-COVID-Oliver-508.pdf

2. FDA. Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-adjuvanted

3. Dubovsky F. NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax COVID-19 vaccine) in adults (≥ 18 years of age). Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/04-covid-dubovsky-508.pdf

4. Twentyman E. Evidence to recommendation framework: Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted in adults ages 18 years and older. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/05-covid-twentyman-508.pdf

5. Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, et al. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data—United States, March 2020–January 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1228-1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5

6. American Hospital Association. FDA limits J&J COVID-19 vaccine use to certain adults. Published May 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. www.aha.org/news/headline/2022-05-06-fda-limits-jj-covid-19-vaccine-use-certain-adults

1. Oliver S. Evidence to recommendations framework: Bivalent COVID-19 vaccine booster doses. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 1, 2002. Accessed September 6, 2002. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-09-01/08-COVID-Oliver-508.pdf

2. FDA. Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted. Updated August 19, 2022. Accessed August 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-adjuvanted

3. Dubovsky F. NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax COVID-19 vaccine) in adults (≥ 18 years of age). Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/04-covid-dubovsky-508.pdf

4. Twentyman E. Evidence to recommendation framework: Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, adjuvanted in adults ages 18 years and older. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/05-covid-twentyman-508.pdf

5. Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, et al. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data—United States, March 2020–January 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1228-1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5

6. American Hospital Association. FDA limits J&J COVID-19 vaccine use to certain adults. Published May 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. www.aha.org/news/headline/2022-05-06-fda-limits-jj-covid-19-vaccine-use-certain-adults

Vitamins and CVD, cancer prevention: USPSTF says evidence isn’t there

The leading causes of death in the United States are cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer. CVD causes about 800,00 deaths per year (30% of all deaths), and cancer is responsible for about 600,000 deaths annually (21%).1 Many adults—more than 50%—report regular use of dietary supplements, including multivitamins and minerals, to improve their overall health, believing that these supplements’ anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties help prevent CVD and cancer.2 However, this belief is not supported by evidence, according to the US Preventive Services Task Force.

What did the Task Force find? After a recent reassessment of the topic of vitamin and mineral supplementation, the Task Force reaffirmed its position from 2014: There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of vitamins and minerals to prevent CVD and cancer.3

For most of the vitamins and minerals included in the systematic review—vitamins A, C, D, E, and K; B vitamins; calcium; iron; zinc; and selenium—the Task Force could not find sufficient evidence to make a recommendation. It is important to note that if any of these are taken at the recommended levels, there is no evidence of serious harm from using them.

However, there is good evidence to recommend against the use of beta carotene and vitamin E.3 For beta carotene, the harms outweigh the benefits: Its use is associated with an increase in the risk of CVD death, as well as an increased incidence of lung cancer in smokers and those with occupational exposure to asbestos. The evidence on vitamin E indicates that it simply does not provide any cancer or CVD mortality benefit.

How to advise patients. Both the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the American Heart Association state that most nutritional needs can be met through the consumption of nutritional foods and beverages; supplements do not add any benefit for those who consume a healthy diet.4 The updated USPSTF recommendations support this approach for community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults.

For those adults who want to supplement their diets—or who need to do so because of an inability to achieve an adequate diet—urge them to follow the recommendations found in DHHS’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025.4

1. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;69:1-83.

2. Cowan AE, Jun S, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use differs by socioeconomic and health-related characteristics among US adults, NHANES 2011-2014. Nutrients. 2018;10:1114. doi: 10.3390/nu10081114

3. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplementation to prevent cardiovascular disease and cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:2326-2333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8970

4. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Published December 2020. Accessed July 13, 2022. www.dietaryguidelines.gov/current-dietary-guidelines

The leading causes of death in the United States are cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer. CVD causes about 800,00 deaths per year (30% of all deaths), and cancer is responsible for about 600,000 deaths annually (21%).1 Many adults—more than 50%—report regular use of dietary supplements, including multivitamins and minerals, to improve their overall health, believing that these supplements’ anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties help prevent CVD and cancer.2 However, this belief is not supported by evidence, according to the US Preventive Services Task Force.

What did the Task Force find? After a recent reassessment of the topic of vitamin and mineral supplementation, the Task Force reaffirmed its position from 2014: There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of vitamins and minerals to prevent CVD and cancer.3

For most of the vitamins and minerals included in the systematic review—vitamins A, C, D, E, and K; B vitamins; calcium; iron; zinc; and selenium—the Task Force could not find sufficient evidence to make a recommendation. It is important to note that if any of these are taken at the recommended levels, there is no evidence of serious harm from using them.

However, there is good evidence to recommend against the use of beta carotene and vitamin E.3 For beta carotene, the harms outweigh the benefits: Its use is associated with an increase in the risk of CVD death, as well as an increased incidence of lung cancer in smokers and those with occupational exposure to asbestos. The evidence on vitamin E indicates that it simply does not provide any cancer or CVD mortality benefit.

How to advise patients. Both the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the American Heart Association state that most nutritional needs can be met through the consumption of nutritional foods and beverages; supplements do not add any benefit for those who consume a healthy diet.4 The updated USPSTF recommendations support this approach for community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults.

For those adults who want to supplement their diets—or who need to do so because of an inability to achieve an adequate diet—urge them to follow the recommendations found in DHHS’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025.4

The leading causes of death in the United States are cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer. CVD causes about 800,00 deaths per year (30% of all deaths), and cancer is responsible for about 600,000 deaths annually (21%).1 Many adults—more than 50%—report regular use of dietary supplements, including multivitamins and minerals, to improve their overall health, believing that these supplements’ anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties help prevent CVD and cancer.2 However, this belief is not supported by evidence, according to the US Preventive Services Task Force.

What did the Task Force find? After a recent reassessment of the topic of vitamin and mineral supplementation, the Task Force reaffirmed its position from 2014: There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of vitamins and minerals to prevent CVD and cancer.3

For most of the vitamins and minerals included in the systematic review—vitamins A, C, D, E, and K; B vitamins; calcium; iron; zinc; and selenium—the Task Force could not find sufficient evidence to make a recommendation. It is important to note that if any of these are taken at the recommended levels, there is no evidence of serious harm from using them.

However, there is good evidence to recommend against the use of beta carotene and vitamin E.3 For beta carotene, the harms outweigh the benefits: Its use is associated with an increase in the risk of CVD death, as well as an increased incidence of lung cancer in smokers and those with occupational exposure to asbestos. The evidence on vitamin E indicates that it simply does not provide any cancer or CVD mortality benefit.

How to advise patients. Both the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the American Heart Association state that most nutritional needs can be met through the consumption of nutritional foods and beverages; supplements do not add any benefit for those who consume a healthy diet.4 The updated USPSTF recommendations support this approach for community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults.

For those adults who want to supplement their diets—or who need to do so because of an inability to achieve an adequate diet—urge them to follow the recommendations found in DHHS’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025.4

1. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;69:1-83.

2. Cowan AE, Jun S, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use differs by socioeconomic and health-related characteristics among US adults, NHANES 2011-2014. Nutrients. 2018;10:1114. doi: 10.3390/nu10081114

3. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplementation to prevent cardiovascular disease and cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:2326-2333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8970

4. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Published December 2020. Accessed July 13, 2022. www.dietaryguidelines.gov/current-dietary-guidelines

1. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;69:1-83.

2. Cowan AE, Jun S, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use differs by socioeconomic and health-related characteristics among US adults, NHANES 2011-2014. Nutrients. 2018;10:1114. doi: 10.3390/nu10081114

3. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplementation to prevent cardiovascular disease and cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:2326-2333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8970

4. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Published December 2020. Accessed July 13, 2022. www.dietaryguidelines.gov/current-dietary-guidelines

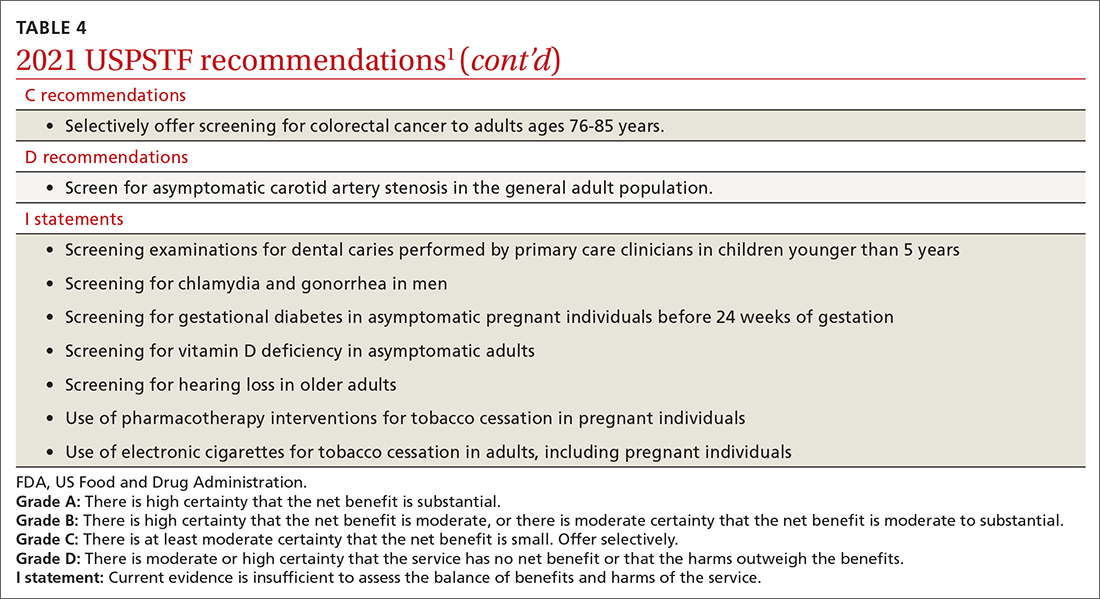

USPSTF updates recommendations on aspirin and CVD

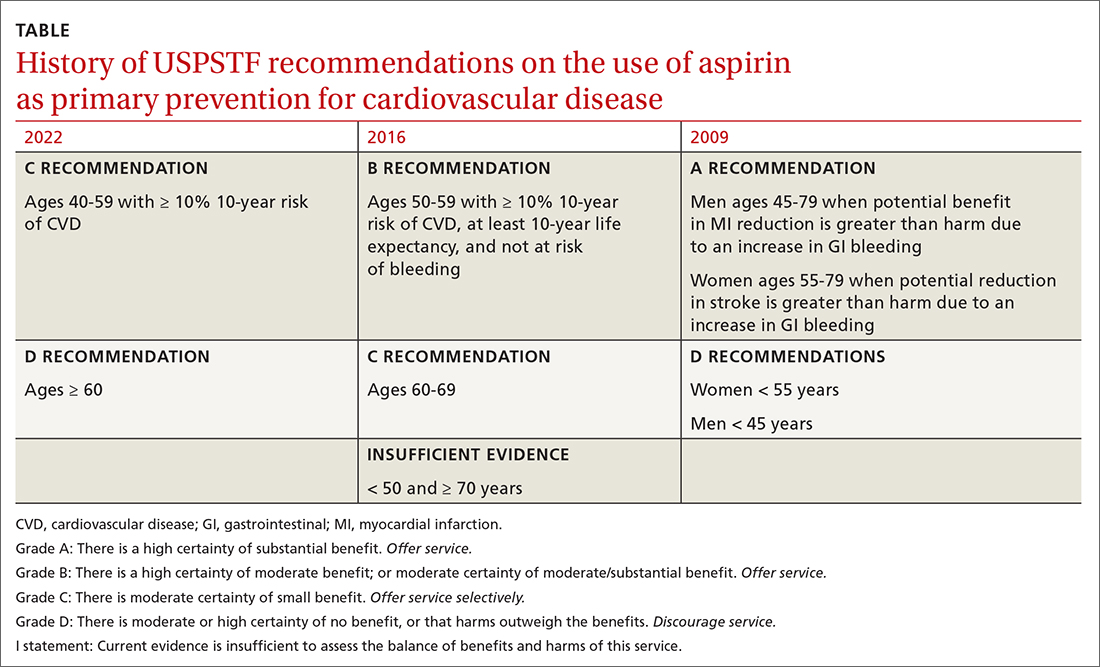

In April 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 These recommendations differ markedly from those issued in 2016.

First, for individuals ages 40 through 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year risk of CVD, the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin to prevent CVD is selective. This is in contrast to the 2016 recommendation that advised offering aspirin to any individual ages 50 to 59 whose 10-year risk of CVD was ≥ 10% and whose life expectancy was at least 10 years (TABLE).

Second, according to the new recommendations, individuals who are ages 60 years and older should not initiate low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD. Previously, selected individuals ages 60 to 69 could be advised to take low-dose aspirin.

The 2016 recommendations also considered the potential benefit of aspirin for preventing colorectal cancer. The 2022 recommendations are silent on this topic, because the USPSTF now concludes that the evidence is insufficient to form an opinion about it.

Important details to keep in mind

These new recommendations pertain to those without signs or symptoms of CVD or known CVD. They do not apply to the use of aspirin for harm reduction or tertiary prevention in those with known CVD. Moreover, the recommendations address the initiation of aspirin at the suggested dose of 81 mg/d, not the continuation of it by those already using it (more on this later). The tool recommended for calculating 10-year CVD risk is the one developed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (www.cvriskcalculator.com).

An ongoing controversy. Daily low-dose aspirin for the prevention of CVD has been controversial for decades. The TABLE shows how USPSTF recommendations on this topic have changed from 2009 to the present. In 2009, the recommendations were primarily based on 2 studies; today, they are based on 13 studies and a microsimulation to estimate the benefits and harms of aspirin prophylaxis at different patient ages.2 This increase in the quantity of the evidence, as well as the elevation in quality, has led to much more nuanced and conservative recommendations. These new recommendations from the USPSTF align much more closely with those of the ACC and the AHA, differing only on the upper age limit at which aspirin initiation should be discouraged (60 years for the USPSTF, 70 for ACC/AHA).

Advise aspirin use selectively per the USPSTF recommendations

Several issues must be addressed when considering daily aspirin use for those ages 40 through 59 years (C recommendation; see TABLE for grade definitions):

- Risk of bleeding is elevated with past or current peptic ulcer disease, diabetes, smoking, high blood pressure, and the use of anti-inflammatory medications, steroids, and anticoagulants.

- The harms from bleeding complications tend to occur early in the use of aspirin and can include gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke.

- The higher the 10-year CVD risk, the greater the benefit from low-dose aspirin.

- Benefits of aspirin for the prevention of CVD increase with the number of years of use.

- If an individual has been taking low-dose aspirin without complications, a reasonable age to discontinue its use is 75 years because little incremental benefit occurs with use after that age.

Continue to: More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms

More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms. What exactly is the absolute benefit and harm from daily low-dose aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD? As one might expect, it varies by age. Researchers used a microsimulation model to examine updated clinical data from systematic reviews. Looking at life years gained, the largest benefit was in men with a 10-year CVD risk of 20% and aspirin initiated between the ages of 40 and 49.3 This resulted in 52.4 lifetime years gained per 1000 people.3 The results from a meta-analysis of 11 studies, published in the evidence report, found an absolute reduction in major CVD events of 0.4% (number needed to treat = 250) and an absolute increase in major bleeds of 0.5% (number needed to harm = 200).2 There was no reduction found for CVD-related or all-cause deaths.

One reason for the increased caution on using aspirin as primary prevention for CVD is the role that statins now play in reducing CVD risk, a factor not accounted for in the studies assessed. It is unknown if the addition of aspirin to statins is beneficial. Remember that the USPSTF recommends the use of a low- to moderate-dose statin in those ages 40 to 75 years if they have one or more CVD risk factors and a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%.4

How aspirin use might change. The use of aspirin for CVD prevention is widespread. One analysis estimates that one-third of those ages 50 years and older are using aspirin for CVD prevention, including 45% of those older than 75.5 If the recommendations from the USPSTF are widely adopted, there could be a gradual decrease in aspirin use for primary prevention with little or no effect on overall population health. Other interventions such as smoking prevention, weight reduction, high blood pressure control, and targeted use of statins—if more widely used—would contribute to the downward trend in CVD deaths that has occurred over the past several decades, with fewer complications caused by regular aspirin use.

Take-home message

Follow these steps when caring for adults ages 40 years and older who do not have known CVD:

1. Assess their 10-year CVD risk using the ACC/AHA tool. If the risk is ≥ 10%:

- Discuss the use of a low- or moderate-dose statin if they are age 75 years or younger.

- Discuss the potential for benefit and harm of low-dose aspirin if they are between the ages of 40 and 59 years.

- Mention to those taking daily low-dose aspirin that it has low benefit if continued after age 75.

2. Perform these interventions:

- Screen for hypertension and high cholesterol.

- Screen for type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in patients up to age 70 years who are overweight or obese.

- Ask about smoking.

- Measure body mass index.

- Offer preventive interventions when any of these CVD risks are found.

1. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Perdue LA, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1585-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3337

3. Dehmer SP, O’Keefe LR, Evans CV, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1598-1607. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3385

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults#:~:text=The%20USPSTF%20recommends%20that%20clinicians,event%20of%2010%25%20or%20greater

5. Rhee TG, Kumar M, Ross JS, et al. Age-related trajectories of cardiovascular risk and use of aspirin and statin among U.S. adults aged 50 or older, 2011-2018. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1272-1282. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17038

In April 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 These recommendations differ markedly from those issued in 2016.

First, for individuals ages 40 through 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year risk of CVD, the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin to prevent CVD is selective. This is in contrast to the 2016 recommendation that advised offering aspirin to any individual ages 50 to 59 whose 10-year risk of CVD was ≥ 10% and whose life expectancy was at least 10 years (TABLE).

Second, according to the new recommendations, individuals who are ages 60 years and older should not initiate low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD. Previously, selected individuals ages 60 to 69 could be advised to take low-dose aspirin.

The 2016 recommendations also considered the potential benefit of aspirin for preventing colorectal cancer. The 2022 recommendations are silent on this topic, because the USPSTF now concludes that the evidence is insufficient to form an opinion about it.

Important details to keep in mind

These new recommendations pertain to those without signs or symptoms of CVD or known CVD. They do not apply to the use of aspirin for harm reduction or tertiary prevention in those with known CVD. Moreover, the recommendations address the initiation of aspirin at the suggested dose of 81 mg/d, not the continuation of it by those already using it (more on this later). The tool recommended for calculating 10-year CVD risk is the one developed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (www.cvriskcalculator.com).

An ongoing controversy. Daily low-dose aspirin for the prevention of CVD has been controversial for decades. The TABLE shows how USPSTF recommendations on this topic have changed from 2009 to the present. In 2009, the recommendations were primarily based on 2 studies; today, they are based on 13 studies and a microsimulation to estimate the benefits and harms of aspirin prophylaxis at different patient ages.2 This increase in the quantity of the evidence, as well as the elevation in quality, has led to much more nuanced and conservative recommendations. These new recommendations from the USPSTF align much more closely with those of the ACC and the AHA, differing only on the upper age limit at which aspirin initiation should be discouraged (60 years for the USPSTF, 70 for ACC/AHA).

Advise aspirin use selectively per the USPSTF recommendations

Several issues must be addressed when considering daily aspirin use for those ages 40 through 59 years (C recommendation; see TABLE for grade definitions):

- Risk of bleeding is elevated with past or current peptic ulcer disease, diabetes, smoking, high blood pressure, and the use of anti-inflammatory medications, steroids, and anticoagulants.

- The harms from bleeding complications tend to occur early in the use of aspirin and can include gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke.

- The higher the 10-year CVD risk, the greater the benefit from low-dose aspirin.

- Benefits of aspirin for the prevention of CVD increase with the number of years of use.

- If an individual has been taking low-dose aspirin without complications, a reasonable age to discontinue its use is 75 years because little incremental benefit occurs with use after that age.

Continue to: More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms

More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms. What exactly is the absolute benefit and harm from daily low-dose aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD? As one might expect, it varies by age. Researchers used a microsimulation model to examine updated clinical data from systematic reviews. Looking at life years gained, the largest benefit was in men with a 10-year CVD risk of 20% and aspirin initiated between the ages of 40 and 49.3 This resulted in 52.4 lifetime years gained per 1000 people.3 The results from a meta-analysis of 11 studies, published in the evidence report, found an absolute reduction in major CVD events of 0.4% (number needed to treat = 250) and an absolute increase in major bleeds of 0.5% (number needed to harm = 200).2 There was no reduction found for CVD-related or all-cause deaths.

One reason for the increased caution on using aspirin as primary prevention for CVD is the role that statins now play in reducing CVD risk, a factor not accounted for in the studies assessed. It is unknown if the addition of aspirin to statins is beneficial. Remember that the USPSTF recommends the use of a low- to moderate-dose statin in those ages 40 to 75 years if they have one or more CVD risk factors and a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%.4

How aspirin use might change. The use of aspirin for CVD prevention is widespread. One analysis estimates that one-third of those ages 50 years and older are using aspirin for CVD prevention, including 45% of those older than 75.5 If the recommendations from the USPSTF are widely adopted, there could be a gradual decrease in aspirin use for primary prevention with little or no effect on overall population health. Other interventions such as smoking prevention, weight reduction, high blood pressure control, and targeted use of statins—if more widely used—would contribute to the downward trend in CVD deaths that has occurred over the past several decades, with fewer complications caused by regular aspirin use.

Take-home message

Follow these steps when caring for adults ages 40 years and older who do not have known CVD:

1. Assess their 10-year CVD risk using the ACC/AHA tool. If the risk is ≥ 10%:

- Discuss the use of a low- or moderate-dose statin if they are age 75 years or younger.

- Discuss the potential for benefit and harm of low-dose aspirin if they are between the ages of 40 and 59 years.

- Mention to those taking daily low-dose aspirin that it has low benefit if continued after age 75.

2. Perform these interventions:

- Screen for hypertension and high cholesterol.

- Screen for type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in patients up to age 70 years who are overweight or obese.

- Ask about smoking.

- Measure body mass index.

- Offer preventive interventions when any of these CVD risks are found.

In April 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 These recommendations differ markedly from those issued in 2016.

First, for individuals ages 40 through 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year risk of CVD, the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin to prevent CVD is selective. This is in contrast to the 2016 recommendation that advised offering aspirin to any individual ages 50 to 59 whose 10-year risk of CVD was ≥ 10% and whose life expectancy was at least 10 years (TABLE).

Second, according to the new recommendations, individuals who are ages 60 years and older should not initiate low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD. Previously, selected individuals ages 60 to 69 could be advised to take low-dose aspirin.

The 2016 recommendations also considered the potential benefit of aspirin for preventing colorectal cancer. The 2022 recommendations are silent on this topic, because the USPSTF now concludes that the evidence is insufficient to form an opinion about it.

Important details to keep in mind

These new recommendations pertain to those without signs or symptoms of CVD or known CVD. They do not apply to the use of aspirin for harm reduction or tertiary prevention in those with known CVD. Moreover, the recommendations address the initiation of aspirin at the suggested dose of 81 mg/d, not the continuation of it by those already using it (more on this later). The tool recommended for calculating 10-year CVD risk is the one developed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (www.cvriskcalculator.com).

An ongoing controversy. Daily low-dose aspirin for the prevention of CVD has been controversial for decades. The TABLE shows how USPSTF recommendations on this topic have changed from 2009 to the present. In 2009, the recommendations were primarily based on 2 studies; today, they are based on 13 studies and a microsimulation to estimate the benefits and harms of aspirin prophylaxis at different patient ages.2 This increase in the quantity of the evidence, as well as the elevation in quality, has led to much more nuanced and conservative recommendations. These new recommendations from the USPSTF align much more closely with those of the ACC and the AHA, differing only on the upper age limit at which aspirin initiation should be discouraged (60 years for the USPSTF, 70 for ACC/AHA).

Advise aspirin use selectively per the USPSTF recommendations

Several issues must be addressed when considering daily aspirin use for those ages 40 through 59 years (C recommendation; see TABLE for grade definitions):

- Risk of bleeding is elevated with past or current peptic ulcer disease, diabetes, smoking, high blood pressure, and the use of anti-inflammatory medications, steroids, and anticoagulants.

- The harms from bleeding complications tend to occur early in the use of aspirin and can include gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke.

- The higher the 10-year CVD risk, the greater the benefit from low-dose aspirin.

- Benefits of aspirin for the prevention of CVD increase with the number of years of use.

- If an individual has been taking low-dose aspirin without complications, a reasonable age to discontinue its use is 75 years because little incremental benefit occurs with use after that age.

Continue to: More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms

More on low-dose aspirin benefits and harms. What exactly is the absolute benefit and harm from daily low-dose aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD? As one might expect, it varies by age. Researchers used a microsimulation model to examine updated clinical data from systematic reviews. Looking at life years gained, the largest benefit was in men with a 10-year CVD risk of 20% and aspirin initiated between the ages of 40 and 49.3 This resulted in 52.4 lifetime years gained per 1000 people.3 The results from a meta-analysis of 11 studies, published in the evidence report, found an absolute reduction in major CVD events of 0.4% (number needed to treat = 250) and an absolute increase in major bleeds of 0.5% (number needed to harm = 200).2 There was no reduction found for CVD-related or all-cause deaths.

One reason for the increased caution on using aspirin as primary prevention for CVD is the role that statins now play in reducing CVD risk, a factor not accounted for in the studies assessed. It is unknown if the addition of aspirin to statins is beneficial. Remember that the USPSTF recommends the use of a low- to moderate-dose statin in those ages 40 to 75 years if they have one or more CVD risk factors and a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%.4

How aspirin use might change. The use of aspirin for CVD prevention is widespread. One analysis estimates that one-third of those ages 50 years and older are using aspirin for CVD prevention, including 45% of those older than 75.5 If the recommendations from the USPSTF are widely adopted, there could be a gradual decrease in aspirin use for primary prevention with little or no effect on overall population health. Other interventions such as smoking prevention, weight reduction, high blood pressure control, and targeted use of statins—if more widely used—would contribute to the downward trend in CVD deaths that has occurred over the past several decades, with fewer complications caused by regular aspirin use.

Take-home message

Follow these steps when caring for adults ages 40 years and older who do not have known CVD:

1. Assess their 10-year CVD risk using the ACC/AHA tool. If the risk is ≥ 10%:

- Discuss the use of a low- or moderate-dose statin if they are age 75 years or younger.

- Discuss the potential for benefit and harm of low-dose aspirin if they are between the ages of 40 and 59 years.

- Mention to those taking daily low-dose aspirin that it has low benefit if continued after age 75.

2. Perform these interventions:

- Screen for hypertension and high cholesterol.

- Screen for type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in patients up to age 70 years who are overweight or obese.

- Ask about smoking.

- Measure body mass index.

- Offer preventive interventions when any of these CVD risks are found.

1. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Perdue LA, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1585-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3337

3. Dehmer SP, O’Keefe LR, Evans CV, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1598-1607. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3385

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults#:~:text=The%20USPSTF%20recommends%20that%20clinicians,event%20of%2010%25%20or%20greater

5. Rhee TG, Kumar M, Ross JS, et al. Age-related trajectories of cardiovascular risk and use of aspirin and statin among U.S. adults aged 50 or older, 2011-2018. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1272-1282. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17038

1. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Perdue LA, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1585-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3337

3. Dehmer SP, O’Keefe LR, Evans CV, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;327:1598-1607. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3385

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults#:~:text=The%20USPSTF%20recommends%20that%20clinicians,event%20of%2010%25%20or%20greater

5. Rhee TG, Kumar M, Ross JS, et al. Age-related trajectories of cardiovascular risk and use of aspirin and statin among U.S. adults aged 50 or older, 2011-2018. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1272-1282. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17038

Monkeypox: What FPs need to know, now

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization are investigating an outbreak of monkeypox cases that have occurred around the world in countries that do not have endemic monkeypox virus.1,2 As of July 5, there have been 6924 cases documented in 52 countries, including 560 cases that have occurred in the United States.2 In the United States, as well as globally, a large proportion of cases have been in men who have sex with men.

First, what is monkeypox? Monkeypox is an orthopox virus that is closely related to variola (smallpox) and vaccinia (the virus used in the smallpox vaccine). It is endemic in western and central Africa and is contracted by contact with an infected mammal (including humans). Transmission can occur through direct contact with infected body fluids or lesions, via infectious fomites, or through respiratory secretions (although this usually requires prolonged exposure).

What is the disease course? The incubation period is 4 to 17 days. The initial symptoms include fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and lymphadenopathy. A rash erupts 1 to 4 days after the prodrome and progresses synchronously from macules to papules to vesicles and then to pustules, which eventually scab over and fall off. In some cases reported in the United States, the rash started in the groin and genital area.

Don’t be fooled by other exanthems. Monkeypox can be confused with chickenpox and molluscum contagiosum (MC). However, the lesions in chickenpox appear asynchronously (all 4 stages present at the same time) and the papules of MC contain a central pit.

Can monkeypox be prevented? There are currently 2 vaccines against orthopox viruses: ACAM2000 and Jynneos. Currently, these vaccines are routinely recommended only for those at occupational risk of orthopox exposure.3

What you should know—and do. Be alert for any patient who presents with a suspicious rash; if there is a possibility of monkeypox, the local public health department should be contacted. They will investigate and collect samples for laboratory testing and will elicit contact names and locations. If monkeypox is confirmed, they may offer close contacts 1 of the 2 vaccines, which if administered within 4 days of exposure can prevent infection.

Advise all patients confirmed to have monkeypox to self-isolate until all skin lesions have healed. Good infection control practices in the clinical setting will prevent spread to staff and other patients.

More information about monkeypox, including images of typical lesions—as well as an update on the current investigation in the United States and worldwide—can be found on the CDC website.4

1. Minhaj FS, Ogale YP, Whitehill F, et al. Monkeypox outbreak—nine states, May 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:764-769. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1

2. CDC. US monkeypox outbreak 2022: situation summary. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

3. Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7122e1

4. CDC. 2022 monkeypox: information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 23, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization are investigating an outbreak of monkeypox cases that have occurred around the world in countries that do not have endemic monkeypox virus.1,2 As of July 5, there have been 6924 cases documented in 52 countries, including 560 cases that have occurred in the United States.2 In the United States, as well as globally, a large proportion of cases have been in men who have sex with men.

First, what is monkeypox? Monkeypox is an orthopox virus that is closely related to variola (smallpox) and vaccinia (the virus used in the smallpox vaccine). It is endemic in western and central Africa and is contracted by contact with an infected mammal (including humans). Transmission can occur through direct contact with infected body fluids or lesions, via infectious fomites, or through respiratory secretions (although this usually requires prolonged exposure).

What is the disease course? The incubation period is 4 to 17 days. The initial symptoms include fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and lymphadenopathy. A rash erupts 1 to 4 days after the prodrome and progresses synchronously from macules to papules to vesicles and then to pustules, which eventually scab over and fall off. In some cases reported in the United States, the rash started in the groin and genital area.

Don’t be fooled by other exanthems. Monkeypox can be confused with chickenpox and molluscum contagiosum (MC). However, the lesions in chickenpox appear asynchronously (all 4 stages present at the same time) and the papules of MC contain a central pit.

Can monkeypox be prevented? There are currently 2 vaccines against orthopox viruses: ACAM2000 and Jynneos. Currently, these vaccines are routinely recommended only for those at occupational risk of orthopox exposure.3

What you should know—and do. Be alert for any patient who presents with a suspicious rash; if there is a possibility of monkeypox, the local public health department should be contacted. They will investigate and collect samples for laboratory testing and will elicit contact names and locations. If monkeypox is confirmed, they may offer close contacts 1 of the 2 vaccines, which if administered within 4 days of exposure can prevent infection.

Advise all patients confirmed to have monkeypox to self-isolate until all skin lesions have healed. Good infection control practices in the clinical setting will prevent spread to staff and other patients.

More information about monkeypox, including images of typical lesions—as well as an update on the current investigation in the United States and worldwide—can be found on the CDC website.4

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization are investigating an outbreak of monkeypox cases that have occurred around the world in countries that do not have endemic monkeypox virus.1,2 As of July 5, there have been 6924 cases documented in 52 countries, including 560 cases that have occurred in the United States.2 In the United States, as well as globally, a large proportion of cases have been in men who have sex with men.

First, what is monkeypox? Monkeypox is an orthopox virus that is closely related to variola (smallpox) and vaccinia (the virus used in the smallpox vaccine). It is endemic in western and central Africa and is contracted by contact with an infected mammal (including humans). Transmission can occur through direct contact with infected body fluids or lesions, via infectious fomites, or through respiratory secretions (although this usually requires prolonged exposure).

What is the disease course? The incubation period is 4 to 17 days. The initial symptoms include fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and lymphadenopathy. A rash erupts 1 to 4 days after the prodrome and progresses synchronously from macules to papules to vesicles and then to pustules, which eventually scab over and fall off. In some cases reported in the United States, the rash started in the groin and genital area.

Don’t be fooled by other exanthems. Monkeypox can be confused with chickenpox and molluscum contagiosum (MC). However, the lesions in chickenpox appear asynchronously (all 4 stages present at the same time) and the papules of MC contain a central pit.

Can monkeypox be prevented? There are currently 2 vaccines against orthopox viruses: ACAM2000 and Jynneos. Currently, these vaccines are routinely recommended only for those at occupational risk of orthopox exposure.3

What you should know—and do. Be alert for any patient who presents with a suspicious rash; if there is a possibility of monkeypox, the local public health department should be contacted. They will investigate and collect samples for laboratory testing and will elicit contact names and locations. If monkeypox is confirmed, they may offer close contacts 1 of the 2 vaccines, which if administered within 4 days of exposure can prevent infection.

Advise all patients confirmed to have monkeypox to self-isolate until all skin lesions have healed. Good infection control practices in the clinical setting will prevent spread to staff and other patients.

More information about monkeypox, including images of typical lesions—as well as an update on the current investigation in the United States and worldwide—can be found on the CDC website.4

1. Minhaj FS, Ogale YP, Whitehill F, et al. Monkeypox outbreak—nine states, May 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:764-769. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1

2. CDC. US monkeypox outbreak 2022: situation summary. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

3. Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7122e1

4. CDC. 2022 monkeypox: information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 23, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

1. Minhaj FS, Ogale YP, Whitehill F, et al. Monkeypox outbreak—nine states, May 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:764-769. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1

2. CDC. US monkeypox outbreak 2022: situation summary. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

3. Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7122e1

4. CDC. 2022 monkeypox: information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 23, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2022.

At what age should you start screening young people for anxiety?

On April 12, 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a draft recommendation on screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. The recommendation states that clinicians should screen for anxiety in those ages 8 to 18 years. This is a “B” recommendation, which means there is moderate certainty that screening for anxiety in these individuals has a moderate net benefit. The USPSTF felt that the evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening at ages 7 years and younger.1

Anxiety is common among young people in America. A survey conducted in 2018-2019 found that 7.8% of children and adolescents (ages 3 to 17 years) had a current anxiety disorder.2 The isolation created by the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with increased rates of clinically significant psychiatric symptoms; one study suggested that in the first year of the pandemic, 20% of young people experienced elevated anxiety symptoms.3,4 Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence also are associated with an increased likelihood of a future anxiety disorder, or depression, in adulthood.

Therapy may improve outcomes. There is evidence that treatment of anxiety disorders can result in improved clinical outcomes. Treatment options include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both.5